Papal coats of arms

Since the Late Middle Ages, each pope has displayed his own personal coat of arms, initially that of his family, and thus not unique to himself alone, but in some cases composed by him with symbols referring to his past or his aspirations.[1][2][3] This personal coat of arms coexists with that of the Holy See.

Although Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303), Pope Eugene IV (1431-1447), Pope Adrian VI (1522-1523) and a few others used no crest above their escutcheon, from Pope John XXII (1316-1334) onward the papal tiara began to appear (a custom maintained until Pope Nicholas V)[4] and, from the time of Nicholas V's successor, Pope Callistus III (1455-1458), the tiara combined with the keys of Peter.[5][1]

Even before the early modern period, a man who did not have a family coat of arms would assume one upon becoming a bishop, as men did when knighted[6] or on achieving some other prominence.[7] Some who already had an episcopal coat of arms altered it on being elected to the papal throne.[1] The last pope who was elected without already being a bishop was Pope Gregory XVI in 1831 and the last who was not even a priest when elected was Pope Leo X in 1513.[8]

In the 16th and 17th century, heraldists also made up fictitious coats of arms for earlier popes, especially of the 11th and 12th centuries.[9] This became more restrained by the end of the 17th century.[10]

External ornaments

Papal coats of arms are traditionally shown with an image of the papal tiara and the keys of Peter as an external ornament of the escutcheon. The tiara is usually set above the escutcheon, while the keys are in saltire, passing behind it (formerly also en cimier, below the tiara and above the shield). In modern times, the dexter and sinister keys are usually shown in gold (or) and silver (argent), respectively. The first depiction of a tiara, still with a single coronet, in connection with papal arms, is on the tomb of Boniface VIII (d. 1303) in the basilica of S. John Lateran.[11] Benedict XVI in 2005 deviated from tradition in replacing the tiara with the mitre and pallium (see Coat of arms of Pope Benedict XVI).

The two keys have been given the interpretation of representing the power to bind and to loose on earth (silver) and in heaven (gold), in reference to Matthew 16:18-19:

- "You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven."

The gold key signifies that the power reaches to heaven and the silver key that it extends to all the faithful on earth, the interlacing indicating the linking between the two aspects of the power, and the arrangement with the handles of the keys at the base symbolizes that the power is in the hands of the pope.[12]

The oldest known representation of the crossed keys beneath the papal tiara in the Coats of arms of the Holy See dates from the time of Pope Martin V (1417–1431). His successor Pope Eugene IV (1431–1447) included it in the design of a silver coin.[13] Martin V also included the keys in his personal arms (those of the Colonna family); however he did not show them as external ornaments, instead placing them in chief on the shield (this example was followed by Urban V and VIII and Alexander VII; Nicolas V seems to have used just the crossed keys and the tiara in an escutcheon. The placing of the keys above the shield becomes the fashion in the early 16th century, so shown on the tomb of Pius III (d. 1503). Adrian VI (1522/3) placed the keys in saltire behind the shield.[14]

High Middle Ages

Heraldry developed out of military insignia from the time of the First Crusade. The first papal coats of arms appeared when heraldry began to be codified in the 12th to 13th centuries. At first, the popes simply used the secular coat of arms of their family. Thus, Pope Innocent IV (1243-1254), who was born Sinibaldo Fieschi, presumably used the Fieschi coat of arms, as did Adrian V (Ottobon de Fieschi), the nephew of Innocent IV.

It is possible that already some 13th-century popes used their secular coat of arms during their papacy: According to Michel Pastoureau, Pope Innocent IV (1243-1254) is likely the first who displayed personal arms, but the first of whom a contemporary coat of arms survives is Pope Boniface VIII (1294-1303).[15] Some sources also indicate family arms (not attributed arms) of the popes of the second half of the 12th century; thus, editions of the Annuario Pontificio of the 1960s presented the arms of the popes beginning with Pope Innocent III (1198-1216),[16] and John Woodward gave those of the popes from Pope Lucius II (1144-1145) onward.[3] Thus, Innocent III (Lothaire de Segni, 1160-1216) and Gregory IX (Ugolin de Segni, 1145-1241) may have used the coat of arms of the Counts of Segni.[17]

The following papal coat of arms should be considered traditional, lacking contemporary attribution. For the popes of noble families, the coats of arms of the family is substituted, and for commoners, the traditional coat of arms as shown in early modern heraldic sources.

| Arms | Description | Pope | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gules a bear rampant proper[18] | Pope Lucius II (Gherardo Caccianemici dal Orso) 1144/5 | ||

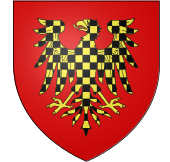

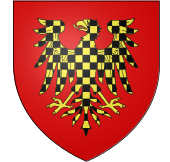

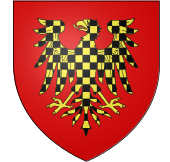

| Arms of the Conti di Segni. Gules, an eagle chequy sable and or, crowned of the second[19] | Pope Innocent III (Lotario dei Conti di Segni) 1198-1216 | the eagle's crown in the Conti arms arose in the 14th century, but is anachronistically also shown in the 13th-century pope's arms |

| Arms of the Savelli family. (Bandato di rosso e d'oro, col capo d'argento caricato di due leoni affrontati, con le branche superiori in protezione di una rosa sulla quale si posa un uccellino, il tutto di rosso)[16] | Pope Honorius III (Cencio Savelli) 1216-1227 | also used by Honorius IV (Giacomo Savelli, 1285-1287) |

| Arms of the Conti di Segni (as Innocent III)[16] | Pope Gregory IX (Ugolino dei Conti di Segni) 1227-1241 | |

| (Di rosso, al leone sorreggente una torre, chiusa e finestrata di nero, merlata alla guelfa, il tutto d'oro)[16] | Pope Celestine IV (Goffredo Castiglioni) 1241-1241 | |

| (Bandato d'argento e d'azzurro)[16] | Pope Innocent IV (Sinibaldo Fieschi) 1241-1254 | used by Innocent IV and also by his nephew Adrian V (Ottobon de Fieschi, 1276) |

| Arms of the Conti di Segni (as Innocent III and Gregory IX)[16] | Pope Alexander IV (Rinaldo dei Conti di Segni) 1254-1261 | |

| (Inquartato, nel primo e nel quarto d'azzurro al giglio d'oro, nel secondo e nel terzo d'argento alla rosa di rosso)[16] | Pope Urban IV (Jacques Pantaléon) 1261-1264 | |

| Clement IV (Gui Foucois, 1265-1268) | The tomb of Clement IV at Viterbo has a shield charged with fleurs-de-lis; these do not appear to have been his personal arms and may instead refer to his French origin.[20] | ||

| Visconti | Gregory X (Teobaldo Visconti, 1271-1276) | ||

| Innocent V (Pierre de Tarentaise, 1276-1276) | |||

| a Portuguese pope; Quarterly, 1 and 4 argent three crescents gules; 2 and 3 sable two pallets or | John XXI (Pedro Julião, 1276-1277) | |

| Orsini family | Nicholas III (Giovanni Gaetano Orsini1277-1280) | ||

| a French pope | Martin IV (Simon de Brion 1281-1285) | ||

| Savelli family | Honorius IV (Giacomo Savelli, 1285-1287) | |

| Nicholas IV (Girolamo Masci, 1288-1292) | |||

| Celestine V (Pietro Angelerio, 1294-1294) | |||

Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

| arms | description | pope | notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argent two bends wavy azure[21] (the field also shown or instead of argent; D'oro alla gemella ondata d'azzurro posta in banda). | Boniface VIII (Benedetto Gaetani, 1294-1303) | An early form of the Gaetani coat of arms. This is the first coat of arms documented to have been used by a pope in contemporary sources (Boniface VIII is depicted with his arms by Giotto di Bondone. |

| Per pale, argent and sable. | Benedict XI (Nicolas Boccasini, 1303-1304) | the chief is shown as Per pale, sable and argent in the Gesta Pontificum Romanorum by Giovanni Palazzo (Venice 1688); later sources depict the entire coat of arms as just per pale, argent and sable. |

| Clement V (1305-1314) | |||

| John XXII (1316-1334) | Beginning with John XII, popes would occasionally surmount their heraldic shield with the tiara (but they did not yet use the keys of Peter).[22] | ||

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

-

Nicholas V (Tommaso Parentucelli; 1447-1455) was the first to use the keys of Peter as heraldic device. He would remain the only pope to choose a coat of arms upon his election (and not use his family arms) until the 18th century (Pope Pius VI). Whether this choice was a demonstration of humility, or due to a lack of a family coat of arms (Parentucelli was the son of a physician) is not known.[1]

-

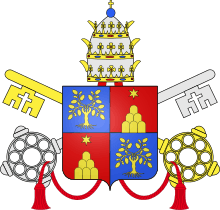

Coat of arms used by Callixtus III (Alfons de Borja, 1455-1458). Beginning with Callixtus III (successor of Nicholas V who used the keys of Peter as heraldic charges), popes began using the keys of Peter with the tiara placed above them as external ornaments of their coats of arms.[1]

-

Coat of arms used by Pius II (Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini, 1458-1464) and by Pius III (1503, born Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini). Francesco Todeschini was received as a boy into the household of Aeneas Silvius, who permitted him to assume the name and arms of the Piccolomini family (his brother Antonio being made Duke of Amalfi during the pontificate of Pius II).

-

Coat of arms used by Paul II (1464-1471)

-

Coat of arms used by Innocent VIII (1484-1492)

-

Coat of arms used by Alexander VI (1492-1503), the second Borgia pope, a coat of arms derived from that of the Borgia family with two keys saltire and a tiara.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Levillain693was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Popes of the Early Modern period

Most popes of the 16th to 18th centuries came from Italian noble families, but there were some exceptions. Sixtus V (1585-1590) was born Felice, son of Pier Gentile (also known as Peretto Peretti), into a poor family. He later adopted Peretti as his family name in 1551, and was known as "Cardinal Montalto". His coat of arms was D'azur au lion d'or armé et lampassé de gueules tenant un rameau d'or à la bande de gueules chargée en chef d'une étoile d'or et en pointe d'un mont à trois cimes d'argent.

-

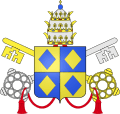

Leo X (1513-1521), the first of the Medici popes. The "augmented coat of arms of the House of Medici, Or, five balls in orle gules, in chief a larger one of the arms of France (viz. Azure, three fleurs-de-lis or) was granted by Louis XI in 1465.[1]

-

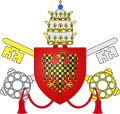

Adrian VI (Adriaan Florenszoon Boeyens (or Dedel), 1522-1523) was a commoner of Utrecht. The tinctures he used are doubtful. The arms showed quarterly, 1 and 4 three tent hooks, 2 and 4 a lion rampant. The hooks may be sable or vert, the lion may be azure or argent.[1] Adrian VI was the first pope to display his arms in the fashion which became standard, with the crossed keys in saltire passing behind the shield.[2]

-

Clement VII (1523-1534), the second of the Medici popes

-

Julius III (1550-1555) Azure, on a bend gules fimbriated and between two olive [sometimes laurel] wreaths or, three mountains, each of as many summits, of the last.[1]

-

Marcellus II (1555), Azure, on a terrace in base vert, a stag lodged argent, between six wheat-stalks [or bulrushes, in reference to Psalm 42] or.[1]

-

Pius IV (1559-1566), the third of the Medici popes, seems to have assumed the "unaugmented" coat of arms, ''Or, six balls in orle gules[1]

-

St. Pius V (1566-1572)

-

Gregory XIII (1572-1585)

-

Sixtus V (1585-1590)

-

Urban VII (Giovanni Battista Castagna, pope for just thirteen days in 1590)

-

Gregory XIV (Niccolò Sfondrati, 1590-1591), son of Francesco Sfondrati

-

Innocent IX (Giovanni Antonio Facchinetti, 1591)

-

Clement VIII (Ippolito Aldobrandini, 1592-1605), used the coat of arms of the Aldobrandini family of Florence

-

Leo XI

(1605), the fourth of the Medici popes -

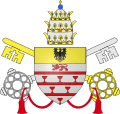

Paul V (Camillo Borghese, 1605-1621). Paul V shows the imperial eagle of the Hohenstaufen in chief, a tradition in Italian heraldry adopted by the Guelphic faction during the War of the Guelphs and Ghibellines

-

Gregory XV

(1621-1623) -

Urban VIII

(1623-1644) -

Innocent X

(1644-1655) -

Alexander VII

(1655-1667) -

Clement IX

(1667-1669) -

Clement X

(1670-1676) -

Bl. Innocent XI

(1676-1689) -

Alexander VIII (Pietro Vito Ottoboni, 1689-1691).

-

Innocent XII

(1691-1700) -

Innocent XIII (Michelangelo Conti, 1721-1724) like Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), Pope Gregory IX (1227–1241) and Pope Alexander IV (1254–1261) was a member of the Conti di Segni, using its coat of arms, which since the 14th century had been mostly shown with the eagle crowned oriental or (also described as in chief a ducal coronet or as the crown is shown somewhat above the eagle's head)

-

Clement XI

(1700-1721) -

Benedict XIII

(1724-1730) -

Clement XII

(1730-1740) -

Benedict XIV

(1740-1758) -

Clement XIII

(1758-1769) -

Clement XIV

(1769-1774) -

Pius VI

(1775-1799)

- ^ a b c d e f g John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 162f.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Woodward153was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Popes of the modern period

The last person elected as pope who was not already an ordained priest or monk was Leo X (Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici) in 1513. Thus, throughout the Early Modern period, the elected pope already had a coat of arms: if he did not have a family coat of arms to begin with, he would have adopted one upon being made bishop. Upon his election as pope, he would continue using his pre-existing coat of arms. This tradition was continued into the modern period, with the sole exception of Joseph Ratzinger, who upon being elected as Benedict XVI in 2005 adopted a new coat of arms based on the earlier coat of arms he used as a bishop.

| Coat of arms | Pope | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pius VII (Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti, 1800-1823) | Per pale, two coats: 1. Azure, a mountain of three coupeaux in base, thereon a patriarchal cross, its arms patées or; over all the word PAX in fess sable; 2. Per bend or and azure, on a bend argent three Moor's heads couped sable wreathed of the third; on a chief of the second three estoiles argent, 1 and 2. The first coat of arms represents the Benedictine order, the second is the Chiaramonti family coat of arms. | |

| Leo XII (Annibale della Genga, 1823-1829) | Azure, an eagle displayed argent; also described as Azure, an eagle displayed or crowned of the same | |

| Pius VIII (Francesco Castiglione, 1829-1830) | Gules, a lion rampant argent holding a castle triple-towered or; as the attributed (traditional) arms of Celestine IV, canting arms for the name "Castiglione" | |

| Gregory XVI (Bartolomeo Capellari, 1831-1846) | Per pale two coats; 1. Azure, two doves argent drinking out of a chalice or, in chief an estoile of the second. 2. Per fess azure and argent over all on a fess gules three mullets or, in chief a hat sable Combining the family arms of Capellari with the arms of the Camaldoli order. | |

| Bl. Pius IX (Giovanni Mastai-Ferretti, 1846-1878) | Quarterly, 1 and 4 azure a lion rampant crowned or, its hind foot resting on a globe of the last [Mastai], 2 and 3 argent two bends gules [Ferretti][23] | |

| Leo XIII (Vincenzo Pecci, 1878-1903) | Azure, on a mount in base a pine tree proper; between in sinister chief a comet, or radiant star, argent, and in base two fleurs-de-lis or. Over all a fess of the third The rays of the comet are usually drawn in bend-sinister, the pine tree is usually drawn like a cypress.[23] | |

| St. Pius X (Giuseppe Sarto, 1903-1914) | Sarto was of humble origin, and he adopted a coat of arms when he became Bishop of Mantua, in 1884: Azure, a three tined anchor in pale above waves of the sea proper, a six pointed star or in chief. As Sarto became Patriarch of Venice in 1893, he added the chief of Venice (a Lion of St. Mark). Sarto changed the field from gules (red) to argent (white) to make the heraldic point that this was the "religious emblem of St. Mark's Lion and not the insignia" of the former Republic of Venice. When he was elected pope in 1903, heraldists expected him to again drop the chief of Venice, but Sarto did not change his coat of arms.[24] | |

| Benedict XV (Giacomo della Chiesa, 1914-1922) | Party per bend azure and or, a church, the tower at sinister, argent, essorée gules, the tower-cross of the second, in chief or, a demi-eagle displayed issuant sable, langued gules. ; the arms of the della Chiesa family with the imperial eagle added in chief.[25] | |

| Pius XI (Ambrogio Ratti, 1922-1939) | Argent three torteaux Gules and on a chief Or an eagle displayed Sable armed Gules. | |

| Ven. Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli, 1939-1958) | ||

| St. John XXIII (Angelo Roncalli, 1958-1963) | John XXIII used the Roncalli family's coat of arms with the addition of the chief of Venice for the Patriarch of Venice (1953), following Pius X. | |

| Bl. Paul VI (Giovanni Montini, 1963-1978) | ||

| John Paul I (Albino Luciani, 1978) | with the chief of Venice for the Patriarch of Venice (1969), following Pius X and John XXIII. | |

| St. John Paul II (Karol Wojtyła, 1978-2005) | Azure a cross or, the upright placed to dexter and the crossbar enhanced, in sinister base an M of the same. (on a blue shield, a golden cross, off-centered to the upper left, with a capital M in the lower right corner). Wojtyła adopted his coat of arms in 1958, when he was created bishop, but with the charges in black instead of gold. As this violated the heraldic "tincture's canon" (black on blue, color on color) upon Wojtyła's election as pope, Vatican heraldist Monsignor Bruno Bernard Heim suggested he replace black by gold.[26] The design shows the "Marian Cross", a cross with a capital M for Mary inscribed in one quarter, recalling "the presence of Mary beneath the cross".[27] | |

| Coat of arms of Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Ratzinger, 2005–2013) | Gules, chape ployé or, with the scallop shell or; the dexter chape with a moor's head proper, crowned and collared gules, the sinister chape a bear trippant (*passant) Proper, carrying a pack gules belted sable.' Designed by Andrea Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo in 2005. The charges, a scallop shell, Moor's head, Corbinian's bear, are taken from his previous coat of arms, used when he was Archbishop of Munich and Freising. Both the Moor's head and Corbinian's bear are charges associated with Freising in Bavaria, Germany. | |

| Coat of arms of Pope Francis (Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 2013-) | Azure on a sun in splendour or the IHS Christogram ensigned with a cross paty fitchy piercing the H gules all above three nails fanwise points to centre sable, and in dexter base a mullet of eight points and in sinister base a spikenard flower or.[28] The gold star represents the Virgin Mary, the grape-like plant – the spikenard – is associated with Saint Joseph and the IHS emblem is the symbol of the Jesuits.[29][30][31] |

Related coats of arms

Notes

- 1 2 3 Coat of Arms of His Holiness Benedict XVI Vatican. Accessed 2008-03-15.

- ↑ Christoph F. Weber, "Heraldry", in Christopher Kleinhenz, Medieval Italy (Routledge 2004 ISBN 978-0-41593930-0), vol. 1, p. 496

- 1 2 "Arms of the Popes from 1144-1893" in John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry (London and Edinburgh 1894), pp. 158-167

- ↑ Collenberg, p. 692

- ↑ Wipertus Rudt De Collenberg, "The Personal Arms of the Popes", within the article "Heraldry" in Philippe Levillain (editor), The Papacy: An Encyclopedia, volume 2, Gaius-proxies (Routledge 2002 ISBN 978-0-41592228-9), p. 693

- ↑ David Brewster, The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia (Routledge 1999 ISBN 978-0-41518026-9), vol. 1, p. 342

- ↑ Christine de Pizan (1364 – c. 1430), The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry (English translation: Penn State Press 1999 ISBN 9780271043050, p. 216

- ↑ Religion News Service, "Popes and conclaves: everything you need to know"

- ↑ Pastoureau 1997, pp. 283–284

- ↑ Ottfried Neubecker (1976). Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-046308-5, p. 224

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 151.

- ↑ "The symbolism of the keys is brought out in an ingenious and interpretative fashion by heraldic art. One of the keys is of gold , the other of silver. The golden key, which points upwards on the dexter side, signifies the power that extends even to Heaven. The silver key, which must point up to the sinister side, symbolizes the power over all the faithful on earth. The two are often linked by a cordon Gules as a sign of the union of the two powers. The handles are turned downwards, for they are in the hand of the Pope, Christ's lieutenant on earth. The wards point upwards, for the power of binding and loosing engages Heaven itself." Bruno Bernhard Heim, Heraldry in the Catholic Church: Its Origin, Customs and Laws (Van Duren 1978 ISBN 9780391008731), p. 54)

- ↑ Claudio Ceresa, "Una sintesi di simboli ispirati alla Scrittura" on L'Osservatore Romano, 10 August 2008

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 153f.

- ↑ Michel Pastoureau (1997). Traité d'Héraldique (3e édition ed.). Picard. p. 49. ISBN 2-7084-0520-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Stemmi dei Sommi Pontefici dal sec. XII ad oggi" in Annuario Pontificio 1969 (Tipografia Poliglotta Vaticana, Vatican City 1969), pp. 23*-27*

- ↑ So presented at heraldique-europeenne.org and araldicavaticana.com

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 158

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 159

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 153.

- ↑ John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 160

- ↑ "Heraldry" in: Philippe Levillain (ed.), Volume 2 of The Papacy: An Encyclopedia (Gaius-Proxies), Routledge, 2002, p. 693.

- 1 2 John Woodward, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry, 1894, p. 167

- ↑ Martin, Cardinal Jacques. Heraldry in the Vatican. Gerrards Cross: Van Duren Publishers, 1987.

- ↑ The "ghibbeline" tradition of the imperial eagle in chief here shown in the variant, "not unique in Italian heraldry", of showing only the upper half of the eagle, presumably for reasons of space, to make the eagle's feature more visible. De Chaignon la Rose (1915), pp. 1, 7.

- ↑ (Raul Pardo, 2 April 2005, Joe McMillan, 20 April 2005). Personal Flag and Arms of John Paul II (crwflags.com)

- ↑ Coat of Arms of Pope John Paul II (vatican.va). "The coat of arms for Pope John Paul II is intended to be a homage to the central mystery of Christianity, that of Redemption. It mainly represents a cross, whose form however does not correspond to any of the usual heraldry models. The reason for the unusual shift of the vertical part of the cross is striking, if one considers the second object included in the Coat of Arms: the large and majestic capital M, which recalls the presence of the Madonna under the Cross and Her exceptional participation in Redemption. The Pontiff’s intense devotion to the Holy Virgin is manifested in this manner." L’Osservatore Romano, 9 November 1978.

- ↑ "Wedvick of Jarlsby - Religious/Francis, H. H. Pope 3".

- ↑ "Vatican releases Pope Francis' coat of arms, motto and ring". The Telegraph. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "Lo Stemma di Papa Francesco". L'Osservatore Romano (Vatican website). Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ↑ "Pope stresses simplicity, ecumenism in inaugural Mass plans". National Catholic Reporter. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

References

- Michael McCarthy, Armoria Pontificalium: A Roll of Papal Arms 1012-2006 (2007), ISBN 9780957794795.

- Donald Lindsay Galbreath, A Treatise on Ecclesiastical Heraldry. Part I. Papal Heraldry (1930), revised ed. by G. Briggs, as Papal heraldry, Heraldry Today (1972).

- P. de Chaignon la Rose, The arms of Benedict XV : an introduction to the study of papal armorials (1915), archive.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to SVG Papal coats of arms. |