Marco Polo

| Marco Polo | |

|---|---|

|

Polo wearing a Tatar outfit, date of print unknown | |

| Born |

15 September 1254 Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Died |

8 January 1324 (aged 69) Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Resting place |

Church of San Lorenzo 45°26′14″N 12°20′44″E / 45.4373°N 12.3455°E |

| Occupation | Merchant |

| Known for | The Travels of Marco Polo |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Spouse(s) | Donata Badoer |

| Children | Fantina, Bellela and Moretta |

| Parent(s) |

Mother: Nicole Anna Defuseh Father: Niccolò Polo |

Marco Polo (![]() i/ˈmɑːrkoʊ ˈpoʊloʊ/; Italian pronunciation: [ˈmarko ˈpɔːlo]; September 15, 1254 – January 8–9, 1324)[1] was an Italian merchant traveller[2][3] whose travels are recorded in Livres des merveilles du monde (Book of the Marvels of the World, also known as The Travels of Marco Polo, c. 1300), a book that introduced Europeans to Central Asia and China.

i/ˈmɑːrkoʊ ˈpoʊloʊ/; Italian pronunciation: [ˈmarko ˈpɔːlo]; September 15, 1254 – January 8–9, 1324)[1] was an Italian merchant traveller[2][3] whose travels are recorded in Livres des merveilles du monde (Book of the Marvels of the World, also known as The Travels of Marco Polo, c. 1300), a book that introduced Europeans to Central Asia and China.

He learned the mercantile trade from his father and uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, who travelled through Asia, and met Kublai Khan. In 1269, they returned to Venice to meet Marco for the first time. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, returning after 24 years to find Venice at war with Genoa; Marco was imprisoned and dictated his stories to a cellmate. He was released in 1299, became a wealthy merchant, married, and had three children. He died in 1324 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Venice.

Marco Polo was not the first European to reach China (see Europeans in Medieval China), but he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. This book inspired Christopher Columbus[4] and many other travellers. There is a substantial literature based on Polo's writings; he also influenced European cartography, leading to the introduction of the Fra Mauro map.

Life

Early life and Asian travel

Marco Polo was born between September 15 and 16, 1254,[5][Note 1] in Venice.[6] His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the Near East, becoming wealthy and achieving great prestige.[7][8] Niccolò and his brother Maffeo set off on a trading voyage before Marco's birth.[5][8]

In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo, while residing in Constantinople, then the capital of the Latin Empire, foresaw a political change; they liquidated their assets into jewels and moved away.[7] According to The Travels of Marco Polo, they passed through much of Asia, and met with the Kublai Khan, a Mongol ruler and founder of the Yuan dynasty.[9] Their decision to leave Constantinople proved timely. In 1261 Michael VIII Palaiologos, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, took Constantinople, promptly burned the Venetian quarter and re-established the Eastern Roman Empire. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded,[10] while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

Meanwhile, Marco Polo's mother died, and an aunt and uncle raised him.[8] He received a good education, learning mercantile subjects including foreign currency, appraising, and the handling of cargo ships;[8] he learned little or no Latin.[7]

In 1269, Niccolò and Maffeo returned to their families in Venice, meeting young Marco for the first time. In 1271, during the rule of Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo, Marco Polo (at seventeen years of age), his father, and his uncle set off for Asia on the series of adventures that Marco later documented in his book. They returned to Venice in 1295, 24 years later, with many riches and treasures. They had travelled almost 15,000 miles (24,000 km).[8]

Genoese captivity and later life

Marco Polo returned to Venice in 1295 with his fortune converted in gemstones.

At this time, Venice was at war with the Republic of Genoa.[11] Polo armed a galley equipped with a trebuchet[12] to join the war. He was probably caught by Genoans in a skirmish in 1296, off the Anatolian coast between Adana and the Gulf of Alexandretta[13] and not during the battle of Curzola (September 1298), off the Dalmatian coast. The latter claim is due to a later tradition (16th Century) recorded by Giovanni Battista Ramusio. [14]

He spent several months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to a fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa,[8] who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes and current affairs from China. The book soon spread throughout Europe in manuscript form, and became known as The Travels of Marco Polo. It depicts the Polos' journeys throughout Asia, giving Europeans their first comprehensive look into the inner workings of the Far East, including China, India, and Japan.[15]

Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299,[8] and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle had purchased a large house in the zone named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo (Corte del Milion). The company continued its activities and Marco soon became a wealthy merchant. Polo financed other expeditions, but never left Venice again. In 1300, he married Donata Badoer, the daughter of Vitale Badoer, a merchant.[16] They had three daughters, Fantina, Bellela, and Moreta.[17]

Death

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On January 8, 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried.[1] He also set free a "Tartar slave" who may have accompanied him from Asia.[18]

He divided up the rest of his assets, including several properties, among individuals, religious institutions, and every guild and fraternity to which he belonged. He also wrote-off multiple debts including 300 lire that his sister-in-law owed him, and others for the convent of San Giovanni, San Paolo of the Order of Preachers, and a cleric named Friar Benvenuto. He ordered 220 soldi be paid to Giovanni Giustiniani for his work as a notary and his prayers.[1] The will, which was not signed by Polo, but was validated by the then relevant "signum manus" rule, by which the testator only had to touch the document to make it abide to the rule of law,[19] was dated January 9, 1324. Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact date of Marco Polo's death cannot be determined, but it was between the sunsets of January 8 and 9, 1324.[1]

Travels of Marco Polo

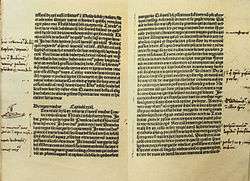

An authoritative version of Marco Polo's book does not and cannot exist, for the early manuscripts differ significantly. The published editions of his book either rely on single manuscripts, blend multiple versions together, or add notes to clarify, for example in the English translation by Henry Yule. The 1938 English translation by A.C. Moule and Paul Pelliot is based on a Latin manuscript found in the library of the Cathedral of Toledo in 1932, and is 50% longer than other versions.[20] Approximately 150 manuscript copies in various languages are known to exist, and before availability of the printing press discrepancies were inevitably introduced during copying and translation.[21] The popular translation published by Penguin Books in 1958 by R.E. Latham works several texts together to make a readable whole.[22]

Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Langues d'Oil, a lingua franca of crusaders and western merchants in the Orient.[23] The idea probably was to create a handbook for merchants, essentially a text on weights, measures and distances.[24]

Narrative

The book opens with a preface describing his father and uncle traveling to Bolghar where Prince Berke Khan lived. A year later, they went to Ukek[25] and continued to Bukhara. There, an envoy from the Levant invited them to meet Kublai Khan, who had never met Europeans.[26] In 1266, they reached the seat of Kublai Khan at Dadu, present day Beijing, China. Kublai received the brothers with hospitality and asked them many questions regarding the European legal and political system.[27] He also inquired about the Pope and Church in Rome.[28] After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). Kublai Khan requested that an envoy bring him back oil of the lamp in Jerusalem.[29] The long sede vacante between the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268 and the election of his successor delayed the Polos in fulfilling Kublai's request. They followed the suggestion of Theobald Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt, and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at the age of fifteen or sixteen.[30]

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfill Kublai's request. They sailed to Acre, and then rode on camels to the Persian port of Hormuz. The Polos wanted to sail straight into China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland through the Silk Road, until reaching Kublai's summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou. In one instance during their trip, the Polos joined a caravan of travelling merchants whom they crossed paths with. Unfortunately, the party was soon attacked by bandits, who used the cover of a sandstorm to ambush them. The Polos managed to fight and escape through a nearby town, but many members of the caravan were killed or enslaved.[31] Three and a half years after leaving Venice, when Marco was about 21 years old, the Polos were welcomed by Kublai into his palace.[8] The exact date of their arrival is unknown, but scholars estimate it to be between 1271 and 1275.[Note 2] On reaching the Yuan court, the Polos presented the sacred oil from Jerusalem and the papal letters to their patron.[7]

Marco knew four languages, and the family had accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience that was useful to Kublai. It is possible that he became a government official;[8] he wrote about many imperial visits to China's southern and eastern provinces, the far south and Burma.[32] His travels also brought him farther to the Bay of Bengal, where he possibly met and gave one of the earliest accounts of the hostile North Sentinelese tribe.[33] Highly respected and sought after in the Mongolian court, Kublai Khan decided to decline the Polos' requests to leave China. They became worried about returning home safely, believing that if Kublai died, his enemies might turn against them because of their close involvement with the ruler. In 1292, Kublai's great-nephew, then ruler of Persia, sent representatives to China in search of a potential wife, and they asked the Polos to accompany them, so they were permitted to return to Persia with the wedding party—which left that same year from Zaitun in southern China on a fleet of 14 junks. The party sailed to the port of Singapore,[34] travelled north to Sumatra,[35] sailed west to the [Point Pedro] port of Jaffna under Savakanmaindan and to Pandyan of Tamilakkam.[36] Eventually Polo crossed the Arabian Sea to Hormuz. The two-year voyage was a perilous one—of the six hundred people (not including the crew) in the convoy only eighteen had survived (including all three Polos).[37] The Polos left the wedding party after reaching Hormuz and travelled overland to the port of Trebizond on the Black Sea, the present day Trabzon.[8] On their long journey home, without the Khan to protect them anymore, the Polos first took refuge in Trebizond in modern-day Turkey. While there, the local government harassed and robbed the Polos of their hard-earned treasures, loosing 4,000 Byzantine gold coins.[38] The Polos managed to escape with their remaining treasure, which they hid by sewing them into their coats. they returned to Italy by 1295, much to the surprise of their family who didn't recognize at first due to their age and other-wordly presence.[8]

Debate

Some minor sources state that Polo was born in the Venetian island of Curzola (present-day Korčula, Croatia).[39][40] The claim is also supported by the Croatian National Tourist Board, which advertises the country as "Croatia, Homeland of Marco Polo",[41] however the lack of evidence makes this theory strongly disputed and even some Croatian scholars consider it just invented.[42]

Skeptics have wondered if Marco Polo actually went to China or if he perhaps wrote his book based on hearsay. While Polo describes paper money and the burning of coal, he fails to mention the Great Wall of China, Chinese characters, chopsticks, or footbinding.[43] Responses to skeptics have stated that if the purpose of Polo's tales was to impress others with tales of his high esteem for an advanced civilization, then it is possible that Polo shrewdly would omit those details that would cause his listeners to scoff at the Chinese with a sense of European superiority; Marco lived among the Mongol elite; foot binding was rare even among Chinese during Polo's time and almost unknown among the Mongols; the Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders, whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo's visit were those very northern invaders; researchers note that the Great Wall familiar to us today is a Ming structure built some two centuries after Marco Polo's travels; and that the Mongol rulers whom Polo served controlled territories both north and south of today's wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications that may have remained there from the earlier dynasties.[44] Other Europeans who traveled to Khanbaliq during the Yuan Dynasty, such as Giovanni de' Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, said nothing about the wall either.[44]

Supporters of the book's basic accuracy have replied. The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that The Book of Marvels was in fact a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa.[45] Rustichello's intention was to use today's language, to write a best-seller, and as such he preferred to stress the fantastic, bizarre and the romantic at the expense of accuracy.[45] Latham has argued that today it is difficult to tell today precisely just how much of The Book of Marvels was Polo and how much Rustichello.[45] However, it is firmly established that the book was written in the same "leisurely, conversational style" that characterized Rustichello's other books, which would very strongly suggest that The Book of Marvels was written by Rustichello with Polo just merely reminiscing about his travels to him.[45] Likewise, the opening introduction in The Book of Marvels to "emperors and kings, dukes and marquises" was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance Rustichello had written several years earlier, and many of the episodes in The Book of Marvels were taken out of the same Arthurian romance to be reset in China.[45] For an example, in his Arthurian romance, Rustichello described the first arrival of Sir Tristan at the court of King Arthur at Camelot; the first meeting described between Polo and Kubla Khan at the latter's court is almost the same right down to the same words used in the Arthurian romance with only Polo inserted in place of Sir Tristan and Kubla Khan in place of King Arthur, and a few other adjustments.[46] In the same way, much of the account of the Siege of Xiangyang is a reworked version of an epic siege by King Arthur described in Rustichello's Arthurian romance.[45] Latham wrote that many of the fantastic aspects in The Book of Marvels were added in by Rusticello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to find in a travel book.[47] As such, the fantastic and bizarre accounts of people with heads of dogs or faces in their chests—which were staples of medieval travel literature—were almost certainly the work of Rustichello. In the same way, Rustichello may have dropped references to ordinary life in China that were presumably of little interest to a European audience.[47] Lathem wrote:

"There are other features of the book that are as likely to be due to Rustichello as to Marco, such as the tendency to glamorize the status of the Polos at the Tartar court, particularly their relation to the princess entrusted to their care, the vein of facetiousness that often accompanies references to their sexual customs and the eagerness to acclaim every exotic novelty as a 'marvel'. It is likely that without the aid of Rustichello Marco would never have written a best-seller. Conceivably he might have produced something not much more readable than Pegolotti's Handbook. More probably he would never have written a book at all"[47]

Latham noted that there are references to daily life, culture, geography and history of China and the Far East in general that would have been unknown to someone like Rusticello, and that could only had come from Polo.[48] As far as it can be established, Rusticello had never been further east than the Holy Land, which he visited as a pilgrim; as such, Rusticello would have known something of the Near East, and the rest of Asia would have been unknown to him.[49] The University of Tübingen Sinologist and historian Hans Ulrich Vogel argued that Polo's description of paper money and salt production supported his presence in China because he included details which he could not have otherwise known.[50] Economic historian Mark Elvin, in his preface to Vogel's 2013 monograph, concludes that Vogel "demonstrates by specific example after specific example the ultimately overwhelming probability of the broad authenticity" of Polo's account. Many problems were caused by the oral transmission of the original text and the proliferation of significantly different hand-copied manuscripts. For instance, did Polo exert "political authority" (seignora) in Yangzhou or merely "sojourn" (sejourna) there. Elvin concludes that "those who doubted, although mistaken, were not always being casual or foolish," but "the case as a whole had now been closed": the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not always final, witness."[51]

Legacy

Further exploration

Other lesser-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo's book meant that his journey was the first to be widely known. Christopher Columbus was inspired enough by Polo's description of the Far East to want to visit those lands for himself; a copy of the book was among his belongings, with handwritten annotations.[4] Bento de Góis, inspired by Polo's writings of a Christian kingdom in the east, travelled 4,000 miles (6,400 km) in three years across Central Asia. He never found the kingdom but ended his travels at the Great Wall of China in 1605, proving that Cathay was what Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) called "China".[52] Marco Polo is also credited with the introduction of sorbet, a forerunner of ice cream, in Europe.[53]

Cartography

Marco Polo's travels may have had some influence on the development of European cartography, ultimately leading to the European voyages of exploration a century later.[54] The 1453 Fra Mauro map was said by Giovanni Battista Ramusio (disputed by historian/cartographer Piero Falchetta, in whose work the quote appears) to have been partially based on the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo:

That fine illuminated world map on parchment, which can still be seen in a large cabinet alongside the choir of their monastery (the Camaldolese monastery of San Michele di Murano) was by one of the brothers of the monastery, who took great delight in the study of cosmography, diligently drawn and copied from a most beautiful and very old nautical map and a world map that had been brought from Cathay by the most honourable Messer Marco Polo and his father.

Though Marco Polo never produced a map that illustrated his journey, his family drew several maps to the Far East based on the wayward's accounts. These collection of maps were signed by Polo's three daughters: Fantina, Bellela and Moreta.[55] Not only did it contain maps of his journey, but also sea routes to Japan, Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, the Bering Strait and even to the coastlines of Alaska, centuries before the rediscovery of Americas by Europeans.

Commemoration

.jpg)

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of Ovis ammon, is named after the explorer,[56] who described it during his crossing of Pamir (ancient Mount Imeon) in 1271.[Note 3]

In 1851, a three-masted Clipper built in Saint John, New Brunswick also took his name; the Marco Polo was the first ship to sail around the world in under six months.[57]

The airport in Venice is named Venice Marco Polo Airport.[58]

The frequent flyer program of Hong Kong flag carrier Cathay Pacific is known as the "Marco Polo Club".[59]

Arts, entertainment, and media

Games

- The game "Marco Polo" is a form of tag played in a swimming pool[60][61] or on land, with slightly modified rules.

- Polo appears as a Great Explorer in the strategy video game Civilization Revolution (2008).[62]

Literature

The travels of Marco Polo are fictionalised in a number works, such as:

- Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne's Messer Marco Polo (1921)[63]

- Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities (1972), in which Polo appears as a pivotal character.

- Gary Jennings' novel The Journeyer (1984)

- James Rollins' SIGMA Force Book 4: The Judas Strain (2007), in which facts about Polo's travels and conjecture about secrets he kept are interleaved with modern-day action.

Television

- The television miniseries, Marco Polo (1982), featuring Ken Marshall and Ruocheng Ying, and directed by Giuliano Montaldo, depicts Polo's travels, won two Emmy Awards, and was nominated for six more.[64][65]

- The television film, Marco Polo (2007), starring Brian Dennehy as Kublai Khan, and Ian Somerhalder as Marco, portrays Marco Polo being left alone in China while his uncle and father return to Venice, to be reunited with him many years later.[66]

- In the Footsteps of Marco Polo (2009) is a PBS documentary about two friends (Denis Belliveau and Francis O'Donnell) who conceived of the ultimate road trip to retrace Marco Polo's journey from Venice to China via land and sea.[67]

- Marco Polo is a television drama series about Marco Polo's early years in the court of Kublai Khan which premiered on Netflix in December 2014.

See also

- Chinese expeditions to the Sinhala Kingdom

- Chronology of European exploration of Asia

- Did Marco Polo go to China?

- Silk Road, which Marco Polo traveled

Notes

- ↑ Many sources state "around 1254"; Britannica 2002, p. 571 states, "born in or around 1254."

- ↑ Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, a Tibetan monk and confidant of Kublai Khan, mentions in his diaries that in 1271 a foreign friend of Kublai Khan visits—quite possibly one of the elder Polos or even Marco Polo himself, although, no name was given. If this is not the case, a more likely date for their arrival is 1275 (or 1274, according to the research of Japanese scholar Matsuo Otagi).(Britannica 2002, p. 571)

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch.18 states, "Then there are sheep here as big as asses; and their tails are so large and fat, that one tail shall weigh some 30 lb. They are fine fat beasts, and afford capital mutton."

References

- 1 2 3 4 Bergreen 2007, pp. 339–342

- ↑ William Tait, Christian Isobel Johnstone (1843), Tait's Edinburgh magazine, Volume 10, Edinburgh

- ↑ Hinds, Kathryn (2002), Venice and Its Merchant Empire, New York

- 1 2 Landström 1967, p. 27

- 1 2 Italiani nel sistema solare di Michele T. Mazzucato

- ↑ Bergreen 2007, p. 25 (online copy pp. 24–25)

- 1 2 3 4 Britannica 2002, p. 571

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Parker 2004, pp. 648–649

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch.1–9

- ↑ Zorzi, Alvise, Vita di Marco Polo veneziano, Rusconi Editore, 1982

- ↑ Nicol 1992, p. 219

- ↑ Yule, The Travels of Marco Polo, London, 1870: reprinted by Dover, New York, 1983.

- ↑ According to fr. Jacopo d'Aqui, Chronica mundi libri imaginis

- ↑ Polo, Marco; Latham, Ronald (translator) (1958). The Travels of Marco Polo, p. 16. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044057-7.

- ↑ Bram 1983

- ↑ Bergreen 2007, p. 532

- ↑ Power 2007, p. 87

- ↑ Britannica 2002, p. 573

- ↑ Biblioteca Marciana, the institute that holds Polo's original copy of his testament. Venezia.sbn.it

- ↑ Bergreen 2007, pp. 367–368

- ↑ Edwards, p. 1

- ↑ The Travels of Marco Polo. (Harmondsworth, Middlesex; New York: Penguin Books, Penguin Classics, 1958; rpr. 1982 etc.)ISBN 0140440577.

- ↑ ^ Marco Polo, Il Milione, Adelphi 2001, ISBN 88-459-1032-6, Prefazione di Bertolucci Pizzorusso Valeria, pp. X–XXI.

- ↑ ^ Larner John, Marco Polo and the discovery of the world, Yale University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-300-07971-0 pp. 68–87.

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 2

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 3

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 5

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 6

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 7

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 9

- ↑ Zelenyj, Alexander, Marco Polo: Overland to China, Crabtree Publishing Company (2005) Chapter: Along the Silk Road. ISBN 978-0778724537

- ↑ W. Marsden (2004), Thomas Wright, ed., The Travels of Marco Polo, The Venetian (1298) (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2009, retrieved February 21, 2013

- ↑ McKie, Robin (February 12, 2006). "Survival comes first for the last Stone Age tribe world". The Guardian. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, p. 281, vol. 3 ch. 8

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, p. 286, vol. 3 ch. 9

- ↑ Yule & Cordier 1923, p. 373, vol. 3 ch. 21

- ↑ Boyle, J. A. (1971). Marco Polo and his Description of the World. History Today. Vol. 21, No. 11. Historyoftoday.com

- ↑ Andrews, Evan (March 12, 2013). "11 Things You May Not Know About Marco Polo". History.

- ↑ Marco Polo and the Silk Road to China by Michael Burgan, Compass Point Books, ISBN 0756501806, p. 7 (This is a book for children)

- ↑ Timothy Brook, The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, 2010, ISBN 9780674046023, p. 24 (This book is unrelated with Polo, who is just mentioned)

- ↑ Homeland of Marco Polo, advertisement of National Croatian Tourist Board

- ↑ Olga Orlić (Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia), The curious case of Marco Polo from Korčula: An example of invented tradition, Journal of Marine and Island Cultures, Volume 2, Issue 1, June 2013, Pages 20–28

- ↑ Frances Wood, Did Marco Polo Go to China? (London: Secker & Warburg; Boulder, Colorado: Westview, 1995).

- 1 2 Haw, Stephen G. (2006), Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan, Volume 3 of Routledge studies in the early history of Asia, Psychology Press, pp. 52–57, ISBN 0-415-34850-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pages 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 page 11.

- ↑ Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pages 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 pages 11–12.

- 1 2 3 Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pages 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 page 12.

- ↑ Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pages 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 page 12.

- ↑ Latham, Ronald "Introduction" pages 7–20 from The Travels of Marco Polo, London: Folio Society, 1958 page 11.

- ↑ "Marco Polo was not a swindler – he really did go to China". University of Tübingen (Alpha Galileo). 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Hans Ulrich Vogel, Marco Polo Was in China: New Evidence from Currencies, Salts and Revenues (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2013), p. xix

- ↑ Winchester 2008, p. 264

- ↑ Upton, Emily (June 16, 2013). "THE HISTORY OF ICE CREAM". Today I Found Out.

- 1 2 Falchetta 2006, p. 592

- ↑ Klein, Christopher (September 30, 2014). "Did Marco Polo Visit Alaska?". History.

- ↑ Bergreen 2007, p. 74

- ↑ Lubbock 2008, p. 86

- ↑ Brennan, D. (February 1, 2009), Lost in Venice, WalesOnline, archived from the original on August 30, 2009, retrieved July 15, 2009

- ↑ Cathay Pacific Airways (2009), The Marco Polo Club, Cathay Pacific Airways Limited, retrieved July 13, 2009

- ↑ Bittarello, Maria Beatrice (2009). "Marco Polo". In Rodney P. Carlisle. Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society. SAGE. ISBN 1-4129-6670-1.

- ↑ Jeffrey, Phillip; Mike Blackstock; Matthias Finke; Anthony Tang; Rodger Lea; Meghan Deutscher; Kento Miyaoku. "Chasing the Fugitive on Campus: Designing a Location-based Game for Collaborative Play". Proceedings of CGSA 2006 Symposium (Canadian Games Study Association).

- ↑ "Civilization Revolution: Great People]". CivFanatics. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ↑ Donn-Byrne, Brian Oswald (1921). Messer Marco Polo.

- ↑ Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, retrieved July 6, 2009 (Searching for "Marco Polo", and year 1982)

- ↑ "Marco Polo". IMDb TV miniseries. 1982.

- ↑ "Marco Polo". IMDb TV miniseries. 2007.

- ↑ "In the footsteps of Marco Polo (PBS)". WLIW.org. 2009.

Bibliography

- Basil, Lubbock (2008), The Colonial Clippers, Read Books, ISBN 978-1-4437-7119-1

- Bergreen, Laurence (2007), Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu, London: Quercus, ISBN 978-1-84724-345-4

- Bram, Leon L.; Robert S., Phillips; Dickey, Norma H. (1983), Funk & Wagnalls New Encyclopedia, New York: Funk & Wagnalls, ISBN 978-0-8343-0051-4 (Article republished in 2006 World Almanac Books, available online from History.com)

- Brook, Timothy (2010), The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-04602-1

- Burgan, Michael (2002), Marco Polo: Marco Polo and the silk road to China, Mankato: Compass Point Books, ISBN 978-0-7565-0180-8

- Edwards, Mike (2005), Marco Polo, Part 1, Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society

- Falchetta, Piero (2006), Fra Mauro's World Map, Turnhout: Brepols, ISBN 2-503-51726-9

- Landström, Björn (1967), Columbus: the story of Don Cristóbal Colón, Admiral of the Ocean, New York City: Macmillan

- Marco Polo. (2010). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-08-28, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/468139/Marco-Polo

-

"Marco Polo". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Marco Polo". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - "Marco Polo", The New Encyclopædia Britannica Macropedia 9 (15 ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc, 2002, ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2

- "Marco Polo", Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish) (Uggleupplagan ed.), 1915

- McKay, John; Hill, Bennet; Buckler, John (2006), A History of Western Society (Eighth ed.), Houghton Mifflin Company, p. 506, ISBN 0-618-52266-2

- Nicol, Donald M. (1992), Byzantium and Venice: a study in diplomatic and cultural relations, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42894-7

- Parker, John (2004), "Marco Polo", The World Book Encyclopedia 15 (illustrated ed.), United States: World Book, Inc., ISBN 978-0-7166-0104-3

- Power, Eileen Edna (2007), Medieval People, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 978-1-4264-6777-6

- Olivier Weber, Le grand festin de l’Orient; Robert Laffont, 2004

- Winchester, Simon (May 6, 2008), The Man Who Loved China: Joseph Needham and the Making of a Masterpiece, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-088459-8

- Wood, Frances (1998), Did Marco Polo Go To China?, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-8999-2

- Yule, Henry; Cordier, Henri (1923), The Travels Of Marco Polo, Mineola: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-27586-4

Further reading

- Daftary, Farhad (1994). The Assassin legends: myths of the Ismaʻilis (2 ed.). I.B. Tauris. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-85043-705-5.

- Dalrymple, William (1989). In Xanadu.

- Hart, H. Henry (1948). Marco Polo, Venetian Adventurer. Kessinger Publishing.

- Marco Polo (1918). Marsden, William, ed. The Travels of Marco Polo. London: J.M. Dent & Sons. p. 461. Retrieved May 29, 2011.(Original from the University of Wisconsin – Madison)

- Translated and edited by Moule, A.C & Pelliot, Paul (1938). Marco Polo: The Description of the World. London: George Routledge & Sons. 2 Volumes.

- Otfinoski, Steven (2003). Marco Polo: to China and back. New York: Benchmark Books. ISBN 0-7614-1480-0.

- Polo, Marco & Rustichello of Pisa (January 1, 2004). The Travels of Marco Polo – Volume 1. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Polo, Marco & Rustichello of Pisa (May 1, 2004). The Travels of Marco Polo – Volume 2. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- Olivier Weber, Sur les routes de la soie (On the Silk Roads) (with Reza, Hoëbeke,2007

- Yang, Dori Jones (January 11, 2011). Daughter of Xanadu. Delacorte Press Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-385-73923-8. (Young Adult novel)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marco Polo |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marco Polo. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Marco Polo |

On the trail of Marco Polo travel guide from Wikivoyage

On the trail of Marco Polo travel guide from Wikivoyage- Marco Polo at DMOZ

- Marco Polo at the Internet Movie Database

- Marco Polo's house in Venice, near the church of San Giovanni Grisostomo

- National Geographic Marco Polo: Journey from Venice to China

- Works by Marco Polo at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marco Polo at Internet Archive

- Works by Marco Polo at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

|