Poinsot's ellipsoid

In classical mechanics, Poinsot's construction (after Louis Poinsot) is a geometrical method for visualizing the torque-free motion of a rotating rigid body, that is, the motion of a rigid body on which no external forces are acting. This motion has four constants: the kinetic energy of the body and the three components of the angular momentum, expressed with respect to an inertial laboratory frame. The angular velocity vector  of the rigid rotor is not constant, but satisfies Euler's equations. Without explicitly solving these equations, Louis Poinsot was able to visualize the motion of the endpoint of the angular velocity vector. To this end he used the conservation of kinetic energy and angular momentum as constraints on the motion of the angular velocity vector

of the rigid rotor is not constant, but satisfies Euler's equations. Without explicitly solving these equations, Louis Poinsot was able to visualize the motion of the endpoint of the angular velocity vector. To this end he used the conservation of kinetic energy and angular momentum as constraints on the motion of the angular velocity vector  . If the rigid rotor is symmetric (has two equal moments of inertia), the vector

. If the rigid rotor is symmetric (has two equal moments of inertia), the vector  describes a cone (and its endpoint a circle). This is the torque-free precession of the rotation axis of the rotor.

describes a cone (and its endpoint a circle). This is the torque-free precession of the rotation axis of the rotor.

Angular kinetic energy constraint

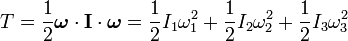

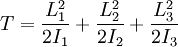

In the absence of applied torques, the angular kinetic energy  is conserved so

is conserved so  .

.

The angular kinetic energy may be expressed in terms of the moment of inertia tensor  and the angular velocity vector

and the angular velocity vector

where  are the components of the angular velocity vector

are the components of the angular velocity vector  along the principal axes, and the

along the principal axes, and the  are the principal moments of inertia. Thus, the conservation of kinetic energy imposes a constraint on the three-dimensional angular velocity vector

are the principal moments of inertia. Thus, the conservation of kinetic energy imposes a constraint on the three-dimensional angular velocity vector  ; in the principal axis frame, it must lie on an ellipsoid, called inertia ellipsoid.

; in the principal axis frame, it must lie on an ellipsoid, called inertia ellipsoid.

The ellipsoid axes values are the half of the principal moments of inertia. The path traced out on this ellipsoid by the angular velocity vector  is called the polhode (coined by Poinsot from Greek roots for "pole path") and is generally circular or taco-shaped.

is called the polhode (coined by Poinsot from Greek roots for "pole path") and is generally circular or taco-shaped.

Angular momentum constraint

In the absence of applied torques, the angular momentum vector  is conserved in an inertial reference frame

is conserved in an inertial reference frame

.

.

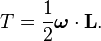

The angular momentum vector  can be expressed

in terms of the moment of inertia tensor

can be expressed

in terms of the moment of inertia tensor  and the angular velocity vector

and the angular velocity vector

which leads to the equation

Since the dot product of  and

and  is constant, and

is constant, and  itself is constant, the angular velocity vector

itself is constant, the angular velocity vector  has a constant component in the direction of the angular momentum vector

has a constant component in the direction of the angular momentum vector

. This imposes a second constraint on the vector

. This imposes a second constraint on the vector  ; in absolute space, it must lie on an

invariable plane defined by its dot product with the conserved vector

; in absolute space, it must lie on an

invariable plane defined by its dot product with the conserved vector  . The normal vector to the invariable plane is aligned with

. The normal vector to the invariable plane is aligned with  . The path traced out by the angular velocity vector

. The path traced out by the angular velocity vector  on the invariable plane is called the herpolhode (coined from Greek roots for "serpentine pole path").

on the invariable plane is called the herpolhode (coined from Greek roots for "serpentine pole path").

Tangency condition and construction

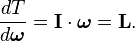

These two constraints operate in different reference frames; the ellipsoidal constraint holds in the (rotating) principal axis frame, whereas the invariable plane constant operates in absolute space. To relate these constraints, we note that the gradient vector of the kinetic energy with respect to angular velocity vector  equals the angular momentum vector

equals the angular momentum vector

Hence, the normal vector to the kinetic-energy ellipsoid at  is

proportional to

is

proportional to  , which is also true of the invariable plane.

Since their normal vectors point in the same direction, these two surfaces will intersect tangentially.

, which is also true of the invariable plane.

Since their normal vectors point in the same direction, these two surfaces will intersect tangentially.

Taken together, these results show that, in an absolute reference frame, the instantaneous angular velocity vector  is the point of intersection between a fixed invariable plane and a kinetic-energy ellipsoid that is tangent to it and rolls around on it without slipping. This is Poinsot's construction.

is the point of intersection between a fixed invariable plane and a kinetic-energy ellipsoid that is tangent to it and rolls around on it without slipping. This is Poinsot's construction.

Derivation of the polhodes in the body frame

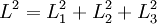

In the principal axis frame (which is rotating in absolute space), the angular momentum vector is not conserved even in the absence of applied torques, but varies as described by Euler's equations. However, in the absence of applied torques, the magnitude  of the angular momentum and the kinetic energy

of the angular momentum and the kinetic energy  are both conserved

are both conserved

where the  are the components of the angular momentum vector along the principal axes, and the

are the components of the angular momentum vector along the principal axes, and the  are the principal moments of inertia.

are the principal moments of inertia.

These conservation laws are equivalent to two constraints to the three-dimensional angular momentum vector  .

The kinetic energy constrains

.

The kinetic energy constrains  to lie on an

ellipsoid, whereas the angular momentum constraint constrains

to lie on an

ellipsoid, whereas the angular momentum constraint constrains

to lie on a sphere. These two surfaces

intersect in taco-shaped curves that define the possible solutions

for

to lie on a sphere. These two surfaces

intersect in taco-shaped curves that define the possible solutions

for  .

.

This construction differs from Poinsot's construction because it considers

the angular momentum vector  rather than the angular velocity vector

rather than the angular velocity vector  . It appears to have been developed by Jacques Philippe Marie Binet.

. It appears to have been developed by Jacques Philippe Marie Binet.

References

- Poinsot (1834) Theorie Nouvelle de la Rotation des Corps, Bachelier, Paris.

- Landau LD and Lifshitz EM (1976) Mechanics, 3rd. ed., Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-021022-8 (hardcover) and ISBN 0-08-029141-4 (softcover).

- Goldstein H. (1980) Classical Mechanics, 2nd. ed., Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02918-9

- Symon KR. (1971) Mechanics, 3rd. ed., Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-07392-7