Playing card

A playing card is a piece of specially prepared heavy paper, thin cardboard, plastic-coated paper, cotton-paper blend, or thin plastic, marked with distinguishing motifs and used as one of a set for playing card games. Playing cards are typically palm-sized for convenient handling.

A complete set of cards is called a pack (UK English), deck (US English), or set (Universal), and the subset of cards held at one time by a player during a game is commonly called a hand. A pack of cards may be used for playing a variety of card games, with varying elements of skill and chance, some of which are played for money (e.g., poker and blackjack games at a casino). Playing cards are also used for illusions, cardistry, building card structures, cartomancy and memory sport.

The front (or "face") of each card carries markings that distinguish it from the other cards in the pack and determine its use under the rules of the game being played. The back of each card is identical for all cards in any particular pack to create an imperfect information scenario. Usually every card will be smooth; however, some packs have braille to allow blind people to read the card number and suit.

Dedicated deck card games have sets that are used only for a specific game. The cards described in this article are used for many games and share a common origin stemming from the standards set in Mamluk Egypt. These sets divide their cards into four suits each consisting of three face cards and numbered or "pip" cards.

History

Early history

Playing cards were invented in Imperial China.[1][2][3] They were found in China as early as the 9th century during the Tang dynasty (618–907).[4][5][6] The first reference to card games dates from the 9th century, when the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang, written by Tang dynasty writer Su E, described Princess Tongchang, daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the "leaf game" in 868 with members of the Wei clan, the family of the princess' husband.[3][7][8]:131 The first known book on the "leaf" game was called Yezi Gexi and was allegedly written by a Tang era woman, and was commented on by Chinese writers of subsequent dynasties.[2] The Song dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserted that the "leaf" game existed at least since the mid-Tang dynasty and associated their invention with the simultaneous development of using sheets or pages instead of paper rolls as a writing medium.[2][3] However, Ouyang claimed the "leaves" were pages of a book for a board game played with dice.[9] In any case, Ouyang asserted that the rules for the game were lost by 1067.

It may be that the first pack of cards ever printed was a 32-card Chinese domino pack, in whose cards all 21 combinations of a pair of dice are depicted. In Gui Tian Lu (歸田錄), a Chinese text redacted in the 11th century, domino cards were printed during the Tang dynasty, contemporary to the first printed books. There is difficulty distinguishing paper cards and gaming tiles in many early sources as the Chinese word pái (牌) is used to describe both. Playing cards are paper pái while tiles are called bone pái. Paper playing cards and the woodblocks to print them are unambiguously attested in 1294.

William Henry Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which were both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for,[1] as in trading card games. As using paper money was inconvenient and risky, they were substituted by play money known as "money cards". One of the earliest games in which we know the rules is Madiao, a trick-taking game, which dates to the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). 15th century scholar Lu Rong described it is as being played with 38 "money cards" divided into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), 9 in myriads (of coins or of strings), and 11 in tens of myriads (a myriad is 10,000). The latter two suits had Water Margin characters instead of pips on them [8]:132 with Chinese ideograms to mark their rank and suit. The suit of coins is in reverse order with 9 of coins being the lowest going up to 1 of coins as the high card.[10] Inverted ranking is also found in the Vietnamese game of Tổ tôm and other games below.

The money-suited system is based on denominations of currency and not on the pips or pictures. This is why there is no tenth rank as that would create a new suit. A simplified deck is still in use by Hakka players, where every suit has just nine cards in progressive ranking, replacing pips and pictures with labels. Another type of modern deck keeps the traditional images but drops the highest suit (tens of myriads) and quadruplicate the rest. The designs on modern Mahjong tiles likely evolved from this pack.

Persia and India

It is not known when playing cards arrived in Persia. They may have been acquired through trade in the Silk Road or brought by the Mongol conquerors in the 13th century. Persian cards, known as Ganjifeh or Ganjafa, have eight suits. Mughal conquerors brought these cards to India in the early 16th century where they are called Ganjifa. In India, current packs used for play have eight, ten, or twelve suits though as many as 32 suits once existed. The Indians also converted the original rectangular cards to circular ones. In Iran, the cards were superseded by As-Nas decks during the 19th century.

Despite the wide variety of Ganjifa patterns, the suits show a uniformity of structure. Every suit contains twelve cards with the top two usually being the court cards of king and vizier and the bottom ten being pip cards. Half the suits use reverse ranking for their pip cards.[11] There many different motifs for the suit pips but some include coins, clubs, jugs, and swords which resemble later Mamluk and Latin suits. Michael Dummett speculated that Ganjifa and Mamluk cards may have descended from an earlier deck which consisted of 48 cards divided into four suits each with ten pip cards and two court cards.[12]

Egypt

By the 11th century, playing cards were spreading throughout the Asian continent and later came into Egypt.[8]:309 The oldest surviving cards in the world are four fragments found in the Keir Collection and one in the Benaki Museum. They are dated to the 12th and 13th centuries (late Fatimid, Ayyubid, and early Mamluk periods).[13]

A near complete pack of Mamluk playing cards dating to the 15th century and of similar appearance to the fragments above was discovered by Leo Aryeh Mayer in the Topkapı Palace, Istanbul, in 1939.[14] It is not a complete set and is actually composed of three different packs, probably to replace missing cards.[15] The Topkapı pack originally contained 52 cards comprising four suits: polo-sticks, coins, swords, and cups. Each suit contained ten pip cards and three court cards, called malik (king), nā'ib malik (viceroy or deputy king), and thānī nā'ib (second or under-deputy). The thānī nā'ib is a non-existent title so it may not have been in the earliest versions; without this rank, the Mamluk suits would structurally be the same as a Ganjifa suit. In fact, the word "Kanjifah" appears in Arabic on the king of swords and is still used in parts of the Middle East to describe modern playing cards. Influence from further east can explain why the Mamluks, most of whom were Central Asian Turkic Kipchaks, called their cups tuman which means myriad in Turkic, Mongolian and Jurchen languages.[16] Wilkinson postulated that the cups may have been derived from inverting the Chinese and Jurchen ideogram for myriad (万).

The Mamluk court cards showed abstract designs or calligraphy not depicting persons possibly due to religious proscription in Sunni Islam, though they did bear the names of military officers. Nā'ib would be corrupted into naibi (Italian) and naipes (Spanish), the latter still in common usage. Panels on the pip cards in two suits show they had a reverse ranking, a feature found in Madiao, Ganjifa, and old European card games like Ombre, Tarot, and Maw.[17]

A fragment of two uncut sheets of Moorish-styled cards of a similar but plainer style were found in Spain and dated to the early 15th century.[18]

Production of these cards did not outlive the fall of the Mamluks in the sixteenth century.[19] The rules to play these games are lost but they are believed to be plain trick games without trumps.[20]

Spread across Europe and early design changes

Playing cards first entered Southern Europe in the 14th century, probably from Mamluk Egypt, using the Mamluk suits of cups, coins, swords, and polo-sticks, which are still used in traditional Latin decks.[21] As polo was an obscure sport to Europeans then, the polo-sticks became batons or cudgels.[22] Their presence is attested in Catalonia in 1371, 1377 in Switzerland, and 1380 in many locations including Florence and Paris.[23][24][25] Wide use of playing cards in Europe can, with some certainty, be traced from 1377 onwards.[26]

A 1369 Paris ordinance does not mention cards, but its 1377 update does. In the account books of Johanna, Duchess of Brabant and Wenceslaus I, Duke of Luxemburg, an entry dated May 14, 1379 reads: "Given to Monsieur and Madame four peters, two forms, value eight and a half moutons, wherewith to buy a pack of cards". In his book of accounts for 1392 or 1393, Charles or Charbot Poupart, treasurer of the household of Charles VI of France, records payment for the painting of three sets of cards.[27]

The earliest cards were made by hand, like those designed for Charles VI; this was expensive. Printed woodcut decks appeared in the 15th century. The technique of printing woodcuts to decorate fabric was transferred to printing on paper around 1400 in Christian Europe, very shortly after the first recorded manufacture of paper there, while in Islamic Spain it was much older. The earliest dated European woodcut is 1418.

From about 1418 to 1450[30] professional card makers in Ulm, Nuremberg, and Augsburg created printed decks. Playing cards even competed with devotional images as the most common uses for woodcuts in this period. Most early woodcuts of all types were coloured after printing, either by hand or, from about 1450 onwards, stencils. These 15th-century playing cards were probably painted. The Flemish Hunting Deck, held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the oldest complete set of ordinary playing cards made in Europe from the fifteenth century.[31] Hunting themed decks like the Stuttgart playing cards and the Ambraser Hofjagdspiel were produced in the Rhine basin during the 15th and 16th centuries. Producers of hunting decks include the Master of the Playing Cards who worked in Germany from the 1430s with the newly invented printmaking technique of engraving. Several other important engravers also made cards, including Master ES and Martin Schongauer. Engraving was much more expensive than woodcut, and engraved cards must have been relatively unusual.

Karnöffel is the oldest card game with which the rules are recorded. It has a complicated "elected suit" that sometimes beat the other suits in certain circumstances. This may have preceded or inspired the creation of the tarot deck. The origins of the tarot pack are thought to be Italian, with the oldest surviving examples dating from the mid-15th century in Milan. It is generally thought that the tarot was invented between 1411 and 1425 by adding a fifth suit of cards known as trionfi (triumphs) to the Italian deck. These trionfi can beat any of the other four suits and is the origin of the word "trump". The tarot deck was never as popular as the standard decks, as it was more expensive, so lower classes preferred smaller decks. In many countries or regions, the regular 52 or 56 card deck shrank to 48, 40, 36, 32, or 24 cards. Instead of having a permanent trump suit like tarot, many trick-taking games starting with Triomphe simply use one or more of the four suits as trumps.

As cards spread from Italy to Germanic countries, the Latin suits were replaced with the suits of Leaves (or Shields), Hearts (or Roses), Bells, and Acorns, and a combination of Latin and Germanic suit pictures and names resulted in the French suits of trèfles (clovers), carreaux (tiles), cœurs (hearts), and piques (pikes) around 1480. The trèfle (clover) was probably derived from the acorn and the pique (pike) from the leaf of the German suits. The names "pique" and "spade", however, may have derived from the sword (spade) of the Italian suits.[32] In England, the French suits were eventually used, although the earliest packs circulating may have had Latin suits.[33] This may account to why the English called the clovers "clubs" and the pikes "spades".

In the late 14th century, Europeans changed the Mamluk court cards to represent European royalty and attendants. In a description from 1377, the earliest courts were originally a seated "King", an upper marshal that held his suit symbol up, and a lower marshal that held it down.[34][35] The latter two correspond with the Ober and Unter cards found in German and Swiss playing cards. The Italians and Iberians replaced the Ober/Unter system with the "Knight" and "Fante" or "Sota" before 1390, perhaps to make the cards more visually distinguishable. In England, the lowest court card was called the "Knave" which originally meant male child (cf German Knabe), so in this context the character could represent the "prince", son to the King and Queen; the meaning servant developed later.[36][37] Queens appeared sporadically in packs as early as 1377, especially in Germany. Although the Germans abandoned the Queen before the 1500s, the French permanently picked it up and placed it under the King. Packs of 56 cards containing in each suit a King, Queen, Knight, and Knave (as in tarot) were once common in the 15th century.

Court cards designed in the 16th century in the manufacturing centre of Rouen became the standard pattern in England, while the Parisian pattern became standard in France. Both the Parisian and Rouennais court cards were named after historical and mythological heroes and heroines. The Parisian names are still printed on cards in France while the Rouennais names were never used in England.

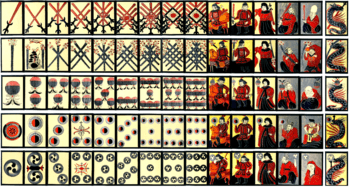

During the mid 16th century, Portuguese traders introduced playing cards to Japan. The first indigenous Japanese deck was the Tenshō karuta named after the Tenshō period.[38] It was a 48 card deck with the 10s missing like Iberian decks from that period. The Tokugawa shogunate banned these cards in the early 17th century forcing Japanese manufacturers to radically redesign their cards. As a result of Japan's isolationist Sakoku policy, karuta would develop separately from the rest of the world. Modern decks like hanafuda bear no resemblance to their Portuguese ancestor.

Later design changes

In early games the kings were always the highest card in their suit. However, as early as the late 15th century special significance began to be placed on the nominally lowest card, now called the Ace, so that it sometimes became the highest card and the Two, or Deuce, the lowest. The term "Ace" itself comes from a dicing term in Anglo-Norman language, which is itself derived from the Latin as (the smallest unit of coinage). Another dicing term, trey (3), sometimes shows up in playing card games. Many governments used to raise revenue by imposing a stamp duty on playing cards. As the Ace card has the most blank space, it was usually chosen as the place to bear the stamp which proved the tax was paid. This led to elaborate designs of certain ace cards: the ace of spades in England, the ace of clubs in France, and the ace of diamonds in Russia.

Packs with corner and edge indices (i.e. the value of the card printed at the corner(s) of the card) enabled players to hold their cards close together in a fan with one hand (instead of the two hands previously used). The first such pack known with Latin suits was printed by Infirerra and dated 1693,[39] but this feature was commonly used only from the end of the 18th century. The first Anglo-American deck with this innovation was the Saladee's Patent, printed by Samuel Hart in 1864. In 1870, he and his cousins at Lawrence & Cohen followed up with the Squeezers, the first cards with indices that had a large diffusion.[40]

Before this time, the lowest court card in an English pack was officially termed the Knave, but its abbreviation ("Kn") was too similar to the King ("K") and thus this term did not adapt well to indices. However, from the 17th century the Knave had often been termed the Jack, a term borrowed from the English Renaissance card game All Fours where the Knave of trumps has this name. All Fours was considered a game of the lower classes, so the use of the term Jack at one time was considered vulgar. The use of indices, however, encouraged a formal change from Knave to Jack in English language packs. Other languages faced similar problems when adding corner indices. In Latin languages both the King and Queen begin with the letter "R" while in Germanic and Slavic languages they begin with the letter "K". Like the equivalent chess piece, the Queen was called Dame, Dama or other variations which mean "lady". Scandinavian cards have kept the "Kn" for knaves.

This was followed by the innovation of reversible court cards. This invention is attributed to a French card maker of Agen in 1745. But the French government, which controlled the design of playing cards, prohibited the printing of cards with this innovation. In central Europe (Trappola cards) and Italy (Tarocco Bolognese) the innovation was adopted during the second half of the 18th century. In Great Britain the pack with reversible court cards was patented in 1799 by Edmund Ludlow and Ann Wilcox. The Anglo-American pack with this design was printed around 1802 by Thomas Wheeler.[41] Reversible court cards meant that players had no need to turn upside-down court cards right side up. Before this, other players could often get a hint of what other players' hands contained by watching them reverse their cards. This innovation required abandoning some of the design elements of the earlier full-length courts.

Sharp corners wear out more quickly, and could possibly reveal the card's value, so they were replaced with rounded corners. Before the mid-19th century, British, American, and French players preferred blank backs. The need to hide wear and tear and to discourage writing on the back led cards to have designs, pictures, photos, or advertising on the reverse.[42][43]

During the nineteenth century, the evolution of Tarot packs for cartomancy and for gaming diverged after Etteilla created the first tarot deck dedicated to divination in 1791. The "reading tarots" based on the symbolic designs of the Tarot de Marseille (which were extensively modified to produce the widely known Rider-Waite deck) kept the older style of full-length character art, specific character meanings for the 21 trumps, and the use of the Latin suits (although most of the reading tarots in use today derive from the French Tarot de Marseille). On the other hand, "playing tarots", especially those of France and the Germanic regions, had by the end of the 19th century evolved into a form more resembling the modern playing card pack, with corner indices and easily identifiable number and court cards. The use of the traditional characters for the trumps was largely discarded in favor of more whimsical scenes. The Tarot Nouveau and Industrie und Glück are the most common examples of the current patterns of playing tarot. The Italian Tarocchi packs, however, have largely kept the traditional character identifications of each trump, as well as the Latin suits, though these packs are used almost exclusively for gaming. Tarocco Bolognese and Tarocco Piemontese are examples of Italian-suited playing tarot packs while the Tarocco Siciliano is the only one that uses Spanish pips.

The United States introduced the Joker into the deck. It was devised for the game of Euchre, which spread from Europe to America beginning shortly after the American Revolutionary War. In Euchre, the highest trump card is the Jack of the trump suit, called the right bower (from the German Bauer); the second-highest trump, the left bower, is the Jack of the suit of the same color as trumps. The joker was invented c. 1860 as a third trump, the imperial or best bower, which ranked higher than the other two bowers.[44] The name of the card is believed to derive from juker, a variant name for Euchre.[45][46] The earliest reference to a Joker functioning as a wild card dates to 1875 with a variation of poker.[47]

Modern manufacturing

Most playing cards sold today are either made of card stock or plastic. Commercial grade polyvinyl chloride (PVC) was not available until the late 1920s and the first all PVC cards appeared in 1935. Contemporary plastic cards are increasingly made of polyvinyl chloride acetate (PVCA) or cellulose acetate. Plastic cards last longer and are more durable than paper cards but are more expensive. After World War II, paper cards were given a plastic coating to extend their lifetime.

Cards are printed on unique sheets that undergo a varnishing procedure in order to enhance the brightness and glow of the colours printed on the cards, as well as to increase their durability. Most printing today is done by offset printing or digital printing.

In today’s market, some high-quality products are available. There are some specific treatments on card surfaces, such as calender and linen finishing, that improve shuffling for either professional or domestic use.

The cards are printed on sheets, which are cut and arranged in bands (vertical stripes) before undergoing a cutting operation that cuts out the individual cards. After assembling the new decks, they pass through the corner-rounding process that will confer the final outline: the typical rectangular playing-card shape.

For most decks, the cards are assembled mechanically in an unvarying sequence, so their order must be randomized when play begins. Exceptions are decks destined for casinos which use pre-shuffled cards. Finally, each pack is wrapped in cellophane and inserted in its case, which may also be wrapped and sealed.

Modern deck formats

| Italian | Cups |

Coins |

Clubs |

Swords |

| Spanish | Cups |

Coins |

Clubs |

Swords |

| Swiss German | Roses |

Bells |

Acorns |

Shields |

| German | Hearts |

Bells |

Acorns |

Leaves |

| French | Hearts |

Tiles (Diamonds) |

Clovers (Clubs) |

Pikes (Spades) |

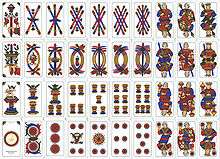

Contemporary playing cards are grouped into three broad categories based on the suits they use: French, Latin, and German. Latin suits are used in the closely related Spanish and Italian formats. The Swiss German suits are distinct enough to merit their subcategory. Excluding Jokers and Tarot trumps, the French 52-card deck preserves the number of cards in the original Mamluk deck, while Latin and German decks average fewer. Latin decks usually drop the higher-valued pip cards, while German decks drop the lower-valued ones.

Within suits, there are regional or national variations called "standard patterns" because they are in the public domain, allowing multiple card manufacturers to copy them.[48] Pattern differences are most easily found in the face cards but the number of cards per deck, the use of numeric indices, or even minor shape and arrangement differences of the pips can be used to distinguish them. Some patterns have been around for hundreds of years. Jokers are not part of any pattern as they are a relatively recent invention and lack any standardized appearance so each publisher usually puts their own trademarked illustration into their decks. The wide variation of jokers has turned them into collectible items. Any card that bore the stamp duty like the ace of spades in England or the ace of clubs in France are also collectible as that is where the manufacturer's logo is usually placed.

French suits

French decks come in a variety of patterns and deck sizes. The 52-card deck is the most popular deck and includes 13 ranks of each suit with reversible "court" or face cards. Each suit includes an Ace, depicting a single symbol of its suit, a King, Queen, and Jack, each depicted with a symbol of their suit; and ranks two through ten, with each card depicting that number of pips of its suit. As well as these 52 cards, commercial packs often include between one and four jokers, most often two.

The piquet pack has all values from 2 through 6 in each suit removed for a total of 32 cards. It is popular in France, the Low Countries, Central Europe and Russia and is used to play Piquet, Belote, Bezique and Skat. 40 card French suited packs are common in northwest Italy; these remove the 8s through 10s like Latin suited decks. 24 card decks, removing 2s through 8s are also sold in Austria and Bavaria to play Schnapsen.

The 78 card Tarot Nouveau adds the Knight card between Queens and Jacks along with 21 numbered trumps and the unnumbered Fool.

German suits

In the German pack, there are four colors, namely Acorns (Eichel), Leaves (Grün or Blatt), Hearts (Herz) and Bells (Schelle). In northern decks, the card ranks are Deuce (Daus or Ass), King (König), Over Knave (Ober), Under Knave (Unter), 10, 9, 8, and 7. Southern decks include the 6 for a total of 36 cards. 24 card "Short" Schafkopf and Schnapsen decks have no 6s, 7s, or 8s. 40-card decks with the 5s can be found in South Tyrol, Italy.

Swiss German suits

The German-speaking Swiss use a variation of the German deck. It uses Roses (Rosen) instead of Hearts and Shields (Schilten) in place of Leaves. Also unlike the German deck, the 10 has been replaced by a Banner card which depicts a flag defaced by its suit symbol. Thus the only true pip cards are 6, 7, 8, and 9. The German Unter card is spelled Under to reflect the local Swiss dialect. They come in 36-card packs and are used to play the national game of Jass.

A less common deck of 48 cards containing the 3s, 4s, and 5s is used to play Kaiserspiel, a variant of Karnöffel.

Latin suits

Latin decks consist of four suits: Swords, Clubs, Cups, and Coins. Spanish style clubs are knobbly cudgels while Italian style clubs are smooth batons. Italian style swords are curved while Spanish style swords are straight. The Portuguese pattern used Spanish pips but intersected their clubs and swords like in Italian suits. The only decks that use the Portuguese pattern in the present is the Sicilian Tarot and some Karuta packs.

Most Italian and Spanish decks consist of 40 cards with each suit numbering 1 (or Ace) to 7 with three face cards of King, Knight, and Knave/Jack.

Italian suits

Despite the name, Italian suits normally refer to only suits found in northeastern Italy (essentially around the former Republic of Venice) while the rest of the country uses Spanish (Sardinia and the south), French (northwest), or German (South Tyrol) suits. They are most commonly found in packs of 40 cards but 52 card sets are also available. The Tarocco Piemontese and Tarocco Bolognese have 78 and 62 cards respectively. Unlike the French deck, some Italian cards do not have any numbers (or letters) identifying their value. The cards' value is determined by identifying the face card or counting the number of suit characters.

Spanish suits

The cards (cartas or naipes in Spanish) are all numbered, but unlike in the standard French pack, the card numbered 10 is the first of the court cards (instead of a card depicting ten pips); so each suit has only twelve cards. Most Spanish games involve forty-card packs, with the 8s and 9s removed, similar to the standard Italian pack. Many Spanish decks have reintroduced cards representing 8 and 9 for a total of 48 cards though 40 card decks are still common.[49] Certain packs include two "comodines" (jokers) as well. The box (la pinta) that goes around the edges of the card is used to distinguish the suit without showing all of your cards: The cups have one interruption, the swords two, the clubs three, and the coins none.

Accessible playing cards

Playing cards have been adapted for use by the visually impaired by the inclusion of large-print and/or braille characters as part of the card. In addition to increasing the size of the suit symbol and the denomination text, large-print cards commonly reduce the visual complexity of the images for simpler identification. They may also omit the patterns of pips in favor of one large pip to identify suit. Some decks have larger indices, often for use in stud poker games, where being able to read cards from a distance is a benefit and hand sizes are small.

Oversize cards are also produced. These can assist with ease of handling and to allow for larger text. Some decks use four colors for the suits in order to make it easier to tell them apart: The most common set of four colors for poker is black spades, red hearts, blue diamonds and green clubs (♠♥♦♣). Another common color set is borrowed from the German suits and uses green spades (leaves) and yellow diamonds (bells) with red hearts and black clubs (♣♠♥♦).

No universal standards for braille playing cards exist. There are many national and producer variations. In most cases each card is marked with two braille characters in the same location as the normal corner markings. The two characters can appear in either vertical (one character below another) or horizontal (two characters side by side). In either case one character identifies the card suit and the other the card denomination. 1 for ace, 2 through 9 for the numbered cards, X (from Roman numerals) or the letter O for ten, J for jack, Q for queen, K for king. The suits are variously marked using D for diamond, S for spade, C or X for club and H or K for heart.

Symbols in Unicode

The Unicode standard for text encoding on computers defines 8 characters for card suits in the Miscellaneous Symbols block, at U+2660–2667. Unicode 7.0 added a unified pack for French-suited Tarot Nouveau's trump cards and the 52 cards of the modern French pack, with 4 Knights, together with a character for "Playing Card Back" and black, red, and white jokers in the block U+1F0A0–1F0FF.[50]

See also

Geographic origin:

- Chinese playing cards

- French playing cards

- Ganjifa

- German playing cards

- Italian playing cards

- Karuta

- Spanish playing cards

- Swiss playing cards

- Tujeon

Types of decks:

- Politicards

- Standard 52-card deck

- Stripped deck

- Tarot

- Trading card

- Transformation playing card

- Trick deck

Specific decks:

Uses:

Terminology:

Sources for further information:

|

|

|

References

- 1 2 Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards". American Anthropologist VIII (1): 61–78. doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070.

- 1 2 3 Needham 2004, p. 132

- 1 2 3 Lo, A. (2009). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 63 (3): 389. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466.

- ↑ Needham 2004, pp. 131–132

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 334 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- ↑ Zhou, Songfang (1997). "On the Story of Late Tang Poet Li He". Journal of the Graduates Sun Yat-sen University 18 (3): 31–35.

- 1 2 3 Needham, Joseph and Tsien Tsuen-hsuin. (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press., reprinted Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.(1986)

- ↑ Parlett, David, "The Chinese "Leaf" Game", March 2015.

- ↑ Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- ↑ Games played with Ganjifa cards at pagat.com

- ↑ Playing card basics at the International Playing-Card Society website

- ↑ Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. Duckworth. p. 41. ISBN 0 7156 1014 7.

- ↑ Mayer, Leo Ary (1939), Le Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale 38, pp. 113–118, retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ International Playing Cards Society Journal, 30-3, page 139

- ↑ Pollett, Andrea "The Playing-Card", Vol. 31, No 1 pp. 34–41.

- ↑ Mamluk cards. Cards.old.no. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ↑ Wintle, Simon. Moorish playing cards at The World of Playing Cards. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ The Mamluk Cards. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ↑ No trump trick-taking games at pagat.com

- ↑ Donald Laycock in Skeptical—a Handbook of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, ed Donald Laycock, David Vernon, Colin Groves, Simon Brown, Imagecraft, Canberra, 1989, ISBN 0-7316-5794-2, p. 67

- ↑ Andy's Playing Cards - The Tarot And Other Early Cards - page XVII - the moorish deck. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ↑ "Trionfi – Tarot and its history". trionfi.co.

- ↑ "Trionfi – Tarot and its history". trionfi.co.

- ↑ J. Brunet i Bellet, Lo joch de naibs, naips o cartas, Barcelona, 1886, quote in the "Diccionari de rims de 1371 : darrerament/per ensajar/de bandejar/los seus guarips/joch de nayps/de nit jugàvem, see also le site trionfi.com

- ↑ Banzhaf, Hajo (1994), Il Grande Libro dei Tarocchi (in Italian), Roma: Hermes Edizioni, pp. 16, 192, ISBN 88-7938-047-8

- ↑ Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p.135. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-80164-7.

- ↑ "Coats of arms of Nantes and of Anne of Brittany (Bretagne)". Europeana. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ↑ The complete proverb is "Cœur de femme trompe le monde, car en elle malice abonde." ("Woman's heart deceives the world, as in her malice abounds"), as reported by Gabriel Meurier in his Trésor des sentences, 1568.

- ↑ "Early Card painters and Printers in Germany, Austria and Flandern (14th and 15th century)". trionfi.com.

- ↑ "Set of Fifty-Two Playing Cards - Label". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Early Playing Cards Research". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "The Introduction of Playing-Cards to Europe". jducoeur.org.

- ↑ History of Playing-Cards at International Playing-Card Society website

- ↑ Wintle, Simon. Early references to Playing Cards at World of Playing Cards.

- ↑ Barrington, Daines (1787). Archaeologia, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity 8. Society of Antiquaries of London. p. 141.

- ↑ "knave, n, 2". Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ↑ Andy's Playing Cards - Japanese and Korean Cards - page 1 ˇ historical and general notes. L-pollett.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2015-05-10.

- ↑ International Playing Cards Society Journal 30-1 page 34

- ↑ Dawson, Tom and Judy. (2014) Hochman Encyclopedia of American Playing Cards. 2nd Ed. Ch 5.

- ↑ International Playing Cards Society Journal. XXVII-5 p. 186; and 31-1 p. 22

- ↑ Fryxell, David A. (2014-02-07) History Matters: Playing Cards. Family Tree Magazine.

- ↑ "Playing cards featuring logo of the FJ Holden". National Museum of Australia.

- ↑ Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, p. 190, ISBN 0-19-214165-1

- ↑ US Playing Card Co. – A Brief History of Playing Cards (archive.org mirror)

- ↑ Beal, George (1975). Playing cards and their story. New York: Arco Publishing Comoany Inc. p. 58

- ↑ Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford Guide to Card Games, Oxford University Press, p. 191, ISBN 0-19-214165-1

- ↑ "Standard pattern notes". I-p-c-s.org. Retrieved 2015-05-10.

- ↑ "Games played with Latin suited cards". pagat.com.

- ↑ Unicode – Playing Cards Block (PDF), retrieved 2014-11-08

Cited sources

- Needham, Joseph (2004), Science & Civilisation in China V:1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05802-3

Further reading

- Griffiths, Antony. Prints and Printmaking British Museum Press (in UK),2nd edn, 1996 ISBN 0-7141-2608-X

- Hind, Arthur M. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ISBN 0-486-20952-0

- Roman du Roy Meliadus de Leonnoys (British Library MS Add. 12228, fol. 313v), c. 1352

- Singer, Samuel Weller (1816), Researches into the History of Playing Cards, R. Triphook

External links

| Look up playing card in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- History of the design of the court cards

- Courts on playing cards

- Deck of playing cards in SVG

- The History of Playing Cards discussed in 1987 by Roger Somerville

- History of Playing Cards

- World Web Playing Cards Museum

- History of playing cards

- The International Playing-Card Society

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|