Plasma stability

An important field of plasma physics is the stability of the plasma. It usually only makes sense to analyze the stability of a plasma once it has been established that the plasma is in equilibrium. "Equilibrium" asks whether there are not forces that will accelerate any part of the plasma. If there are not, then "stability" asks whether a small perturbation will grow, oscillate, or be damped out.

In many cases a plasma can be treated as a fluid and its stability analyzed with magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). MHD theory is the simplest representation of a plasma, so MHD stability is a necessity for stable devices to be used for nuclear fusion, specifically magnetic fusion energy. There are, however, other types of instabilities, such as velocity-space instabilities in magnetic mirrors and systems with beams. There are also rare cases of systems, e.g. the Field-Reversed Configuration, predicted by MHD to be unstable, but which are observed to be stable, probably due to kinetic effects.

Plasma instabilities

Plasma instabilities can be divided into two general groups:

- hydrodynamic instabilities

- kinetic instabilities.

Plasma instabilities are also categorised into different modes:

| Mode (azimuthal wave number) | Note | Description | Radial modes | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m=0 | Sausage instability: displays harmonic variations of beam radius with distance along the beam axis |

n=0 | Axial hollowing | |

| n=1 | Standard sausaging | |||

| n=2 | Axial bunching | |||

| m=1 | Sinuous, kink or hose instability: represents transverse displacements of the beam cross-section without change in the form or in a beam characteristics other than the position of its center of mass |

|||

| m=2 | Filamentation modes: growth leads towards the breakup of the beam into separate filaments. |

Gives an elliptic cross-section | ||

| m=3 | Gives a pyriform (pear-shaped) cross-section | |||

Source: Andre Gsponer, "Physics of high-intensity high-energy particle beam propagation in open air and outer-space plasmas" (2004)[1]

List of plasma instabilities

- Bennett pinch instability (also called the z-pinch instability )

- Beam acoustic instability

- Bump-in-tail instability

- Buneman instability,[2]

- Cherenkov instability,[3]

- Chute instability

- Coalescence instability,[4]

- Collapse instability

- Counter-streaming instability

- Cyclotron instabilities, including:

- Alfven cyclotron instability

- Electron cyclotron instability

- Electrostatic ion cyclotron Instability

- Ion cyclotron instability

- Magnetoacoustic cyclotron instability

- Proton cyclotron instability

- Nonresonant Beam-Type cyclotron instability

- Relativistic ion cyclotron instability

- Whistler cyclotron instability

- Diocotron instability,[5] (similar to the Kelvin-Helmholtz fluid instability).

- Disruptive instability (in tokamaks)

- Double emission instability

- Drift wave instability

- Edge-localized modes[6]

- Electrothermal instability

- Farley-Buneman instability,[7]

- Fan instability

- Filamentation instability

- Firehose instability (also called Hose instability)

- Flute instability

- Free electron maser instability

- Gyrotron instability

- Helical instability (helix instability)

- Helical kink instability

- Hose instability (also called Firehose instability)

- Interchange instability

- Ion beam instability

- Kink instability

- Lower hybrid (drift) instability (in the Critical ionization velocity mechanism)

- Magnetic drift instability

- Magnetorotational instability (in accretion disks)

- Magnetothermal instability (Laser-plasmas)[8]

- Modulation instability

- Non-abelian instability (see also Chromo-Weibel instability)

- Chromo–Weibel instability

- Non-linear coalescence instability

- Oscillating two stream instability, see two stream instability

- Pair instability

- Parker instability (magnetic buoyancy instability)

- Peratt instability (stacked toroids)

- Pinch instability

- Rotating instability,[9]

- Sausage instability

- Slow Drift Instability

- Tearing mode instability

- Two-stream instability

- Weak beam instability

- Weibel instability

MHD Instabilities

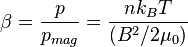

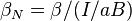

Beta is a ratio of the plasma pressure over the magnetic field strength.

MHD stability at high beta is crucial for a compact, cost-effective magnetic fusion reactor. Fusion power density varies roughly as  at constant magnetic field, or as

at constant magnetic field, or as  at constant bootstrap fraction in configurations with externally driven plasma current. (Here

at constant bootstrap fraction in configurations with externally driven plasma current. (Here  is the normalized beta.) In many cases MHD stability represents the primary limitation on beta and thus on fusion power density. MHD stability is also closely tied to issues of creation and sustainment of certain magnetic configurations, energy confinement, and steady-state operation. Critical issues include understanding and extending the stability limits through the use of a

variety of plasma configurations, and developing active means for reliable operation near those limits. Accurate predictive capabilities are needed, which will require the addition of new physics to existing MHD models. Although a wide range of magnetic configurations exist, the underlying MHD physics is common to all. Understanding of MHD stability gained in one configuration can benefit others, by verifying analytic theories, providing benchmarks for predictive MHD stability codes, and advancing the development of active control techniques.

is the normalized beta.) In many cases MHD stability represents the primary limitation on beta and thus on fusion power density. MHD stability is also closely tied to issues of creation and sustainment of certain magnetic configurations, energy confinement, and steady-state operation. Critical issues include understanding and extending the stability limits through the use of a

variety of plasma configurations, and developing active means for reliable operation near those limits. Accurate predictive capabilities are needed, which will require the addition of new physics to existing MHD models. Although a wide range of magnetic configurations exist, the underlying MHD physics is common to all. Understanding of MHD stability gained in one configuration can benefit others, by verifying analytic theories, providing benchmarks for predictive MHD stability codes, and advancing the development of active control techniques.

The most fundamental and critical stability issue for magnetic fusion is simply that MHD instabilities often limit performance at high beta. In most cases the important instabilities are long wavelength, global modes, because of their ability to cause severe degradation of energy confinement or termination of the plasma. Some important examples that are common to many magnetic configurations are ideal kink modes, resistive wall modes, and neoclassical tearing modes. A possible consequence of violating stability boundaries is a disruption, a sudden loss of thermal energy often followed by termination of the discharge. The key issue thus includes understanding the nature of the beta limit in the various configurations, including the associated thermal and magnetic stresses, and finding ways to avoid the limits or mitigate the consequences. A wide range of approaches to preventing such instabilities is under investigation, including optimization of the configuration of the plasma and its confinement device, control of the internal structure of the plasma, and active control of the MHD instabilities.

Ideal Instabilities

Ideal MHD instabilities driven by current or pressure gradients represent the ultimate operational limit for most configurations. The long-wavelength kink mode and short-wavelength ballooning mode limits are generally well understood and can in principle be avoided. Intermediate-wavelength modes (n ~ 5–10 modes encountered in tokamak edge plasmas, for example) are less well understood due to the computationally intensive nature of the stability calculations. The extensive beta limit database for tokamaks is consistent with ideal MHD stability limits, yielding agreement to within about 10% in beta for cases where the internal profiles of the plasma are accurately measured. This good agreement provides confidence in ideal stability calculations for other configurations and in the design of prototype fusion reactors.

Resistive Wall Modes

Resistive wall modes (RWM) develop in plasmas that require the presence of a perfectly conducting wall for stability. RWM stability is a key issue for many magnetic configurations. Moderate beta values are possible without a nearby wall in the tokamak, stellarator, and other configurations, but a nearby conducting wall can significantly improve ideal kink mode stability in most configurations, including the tokamak, ST, reversed field pinch (RFP), spheromak, and possibly the FRC. In the advanced tokamak and ST, wall stabilization is critical for operation with a large bootstrap fraction. The spheromak requires wall stabilization to avoid the low-m,n tilt and shift modes, and possibly bending modes. However, in the presence of a non-ideal wall, the slowly growing RWM is unstable. The resistive wall mode has been a long-standing issue for the RFP, and has more recently been observed in tokamak experiments. Progress in understanding the physics of the RWM and developing the means to stabilize it could be directly applicable to all magnetic configurations. A closely related issue is to understand plasma rotation, its sources and sinks, and its role in stabilizing the RWM.

Resistive instabilities

Resistive instabilities are an issue for all magnetic configurations, since the onset can occur at beta values well below the ideal limit. The stability of neoclassical tearing modes (NTM) is a key issue for magnetic configurations with a strong bootstrap current. The NTM is a metastable mode; in certain plasma configurations, a sufficiently large deformation of the bootstrap current produced by a “seed island” can contribute to the growth of the island. The NTM is already an important performance-limiting factor in many tokamak experiments, leading to degraded confinement or disruption. Although the basic mechanism is well established, the capability to predict the onset in present and future devices requires better understanding of the damping mechanisms which determine the threshold island size, and of the mode coupling by which other instabilities (such as sawteeth in tokamaks) can generate seed islands. Resistive Ballooning Mode, similar to ideal ballooning, but with finite resistivity taken into consideration, provides another example of a resistive instability.

Opportunities for Improving MHD Stability

Configuration

The configuration of the plasma and its confinement device represent an opportunity to improve MHD stability in a robust way. The benefits of discharge shaping and low aspect ratio for ideal MHD stability have been clearly demonstrated in tokamaks and STs, and will continue to be investigated in experiments such as DIII-D, Alcator C-Mod, NSTX, and MAST. New stellarator experiments such as NCSX (proposed) will test the prediction that addition of appropriately designed helical coils can stabilize ideal kink modes at high beta, and lower-beta tests of ballooning stability are possible in HSX. The new ST experiments provide an opportunity to test predictions that a low aspect ratio yields improved stability to tearing modes, including neoclassical, through a large stabilizing “Glasser effect” term associated with a large Pfirsch-Schlüter current. Neoclassical tearing modes can be avoided by minimizing the bootstrap current in quasi-helical and quasi-omnigenous stellarator configurations. Neoclassical tearing modes are also stabilized with the appropriate relative signs of the bootstrap current and the magnetic shear; this prediction is supported by the absence of NTMs in central negative shear regions of tokamaks. Stellarator configurations such as the proposed NCSX, a quasi-axisymmetric stellarator design, can be created with negative magnetic shear and positive bootstrap current to achieve stability to the NTM. Kink mode stabilization by a resistive wall has been demonstrated in RFPs and tokamaks, and will be investigated in other configurations including STs (NSTX) and spheromaks (SSPX). A new proposal to stabilize resistive wall modes by a flowing liquid lithium wall needs further evaluation.

Internal Structure

Control of the internal structure of the plasma allows more active avoidance of MHD instabilities. Maintaining the proper current density profile, for example, can help to maintain stability to tearing modes. Open-loop optimization of the pressure and current density profiles with external heating and current drive sources is routinely used in many devices. Improved diagnostic measurements along with localized heating and current drive sources, now becoming available, will allow active feedback control of the internal profiles in the near future. Such work is beginning or planned in most of the large tokamaks (JET, JT–60U, DIII–D, C–Mod, and ASDEX–U) using RF heating and current drive. Real-time analysis of profile data such as MSE current profile measurements and real-time identification of stability boundaries are essential components of profile control. Strong plasma rotation can stabilize resistive wall modes, as demonstrated in tokamak experiments, and rotational shear is also predicted to stabilize resistive modes. Opportunities to test these predictions are provided by configurations such as the ST, spheromak, and FRC, which have a large natural diamagnetic rotation, as well as tokamaks with rotation driven by neutral beam injection. The Electric Tokamak experiment is intended to have a very large driven rotation, approaching Alfvénic regimes where ideal stability may also be influenced. Maintaining sufficient plasma rotation, and the possible role of the RWM in damping the rotation, are important issues that can be investigated in these experiments.

Feedback Control

Active feedback control of MHD instabilities should allow operation beyond the “passive” stability limits. Localized rf current drive at the rational surface is predicted to reduce or eliminate neoclassical tearing mode islands. Experiments have begun in ASDEX–U and COMPASS-D with promising results, and are planned for next year in DIII–D. Routine use of such a technique in generalized plasma conditions will require real-time identification of the unstable mode and its radial location. If the plasma rotation needed to stabilize the resistive wall mode cannot be maintained, feedback stabilization with external coils will be required. Feedback experiments have begun in DIII–D and HBT-EP, and feedback control should be explored for the RFP and other configurations. Physics understanding of these active control techniques will be directly applicable between configurations.

Disruption Mitigation

The techniques discussed above for improving MHD stability are the principal means of avoiding disruptions. However, in the event that these techniques do not prevent an instability, the effects of a disruption can be mitigated by various techniques. Experiments in JT–60U have demonstrated reduction of electromagnetic stresses through operation at a neutral point for vertical stability. Pre-emptive removal of the plasma energy by injection of a large gas puff or an impurity pellet has been demonstrated in tokamak experiments, and ongoing experiments in C–Mod, JT–60U, ASDEX–U, and DIII–D will improve the understanding and predictive capability. Cryogenic liquid jets of helium are another proposed technique, which may be required for larger devices. Mitigation techniques developed for tokamaks will be directly applicable to other configurations.

See also

References

- ↑ Physics of high-intensity high-energy particle beam propagation in open air and outer-space plasmas

- ↑ Buneman, O., "Instability, Turbulence, and Conductivity in Current-Carrying Plasma" (1958) Physical Review Letters, vol. 1, Issue 1, pp. 8-9

- ↑ Kho, T. H.; Lin, A. T., "Cyclotron-Cherenkov and Cherenkov instabilities" (1990) IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science (ISSN 0093-3813), vol. 18, June 1990, p. 513-517

- ↑ Finn, J. M.; Kaw, P. K., "Coalescence instability of magnetic islands" (1977) Physics of Fluids, vol. 20, Jan. 1977, p. 72-78. (More citations)

- ↑ Uhm, H. S.; Siambis, J. G., "Diocotron instability of a relativistic hollow electron beam" (1979) Physics of Fluids, vol. 22, Dec. 1979, p. 2377-2381.

- ↑ 11 November, 2003, BBC News: Solar flare 'reproduced' in lab

- ↑ Farley, D. T., "Two-stream plasma instability as a source of irregularities in the ionosphere" (1963) Physical Review Letters, Vol. 10, Issue 7, pp. 279-282; Buneman, O., "Excitation of field aligned sound waves by electron streams" (1963) Physical Review Letters, Vol. 10, Issue 7, pp. 285-287

- ↑ Bissell, J. J., Ridgers, C. P. and Kingham, R. J. "Field Compressing Magnetothermal Instability in Laser Plasmas" (2010) Physical Review Letters, Vol. 105,175001

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Boeuf and Bhaskar Chaudhury , "Rotating Instability in Low-Temperature Magnetized Plasmas" (2013) Physical Review Letters,Vol. 111,155005

- ↑ Wesson, J: "Tokamaks", 3rd edition page 115, Oxford University Press, 2004