Absolute value (algebra)

- This article is about the generalization of the basic concept. For the basic concept, see Absolute value. For other uses, see Absolute value (disambiguation).

In mathematics, an absolute value is a function which measures the "size" of elements in a field or integral domain. More precisely, if D is an integral domain, then an absolute value is any mapping | x | from D to the real numbers R satisfying:

- | x | ≥ 0,

- | x | = 0 if and only if x = 0,

- | xy | = | x || y |,

- | x + y | ≤ | x | + | y |.

It follows from these axioms that | 1 | = 1 and | −1 | = 1. Furthermore, for every positive integer n,

- | n | = | 1 + 1 + ...(n times) | = | −1 − 1 − ...(n times) | ≤ n.

Note that some authors use the terms valuation, norm,[1] or magnitude instead of "absolute value". However, the word "norm" usually refers to a specific kind of absolute value on a field (and which is also applied to other vector spaces).

The classical "absolute value" is one in which, for example, |2|=2. But many other functions fulfill the requirements stated above, for instance the square root of the classical absolute value (but not the square thereof).

Types of absolute value

The trivial absolute value is the absolute value with | x | = 0 when x = 0 and | x | = 1 otherwise.[2] Every integral domain can carry at least the trivial absolute value. The trivial value is the only possible absolute value on a finite field because any element can be raised to some power to yield 1.

If | x + y | satisfies the stronger property | x + y | ≤ max(|x|, |y|), then | x | is called an ultrametric or non-Archimedean absolute value, and otherwise an Archimedean absolute value.

Places

If | x |1 and | x |2 are two absolute values on the same integral domain D, then the two absolute values are equivalent if | x |1 < 1 if and only if | x |2 < 1. If two nontrivial absolute values are equivalent, then for some exponent e, we have | x |1e = | x |2. Raising an absolute value to a power less than 1 results in another absolute value, but raising to a power greater than 1 does not necessarily result in an absolute value. (For instance, squaring the usual absolute value on the real numbers yields a function which is not an absolute value because it would violate the rule |x + y| ≤ |x| + |y|.) Absolute values up to equivalence, or in other words, an equivalence class of absolute values, is called a place.

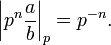

Ostrowski's theorem states that the nontrivial places of the rational numbers Q are the ordinary absolute value and the p-adic absolute value for each prime p.[3] For a given prime p, any rational number q can be written as pn(a/b), where a and b are integers not divisible by p and n is an integer. The p-adic absolute value of q is

Since the ordinary absolute value and the p-adic absolute values are absolute values according to the definition above, these define places.

Valuations

If for some ultrametric absolute value and any base b > 1, we define ν(x) = −logb |x| for x ≠ 0 and ν(0) = ∞, where ∞ is ordered to be greater than all real numbers, then we obtain a function from D to R ∪ {∞}, with the following properties:

- ν(x) = ∞ ⇒ x = 0,

- ν(xy) = ν(x) + ν(y),

- ν(x + y) ≥ min(ν(x), ν(y)).

Such a function is known as a valuation in the terminology of Bourbaki, but other authors use the term valuation for absolute value and then say exponential valuation instead of valuation.

Completions

Given an integral domain D with an absolute value, we can define the Cauchy sequences of elements of D with respect to the absolute value by requiring that for every r > 0 there is a positive integer N such that for all integers m, n > N one has | xm − xn | < r. It is not hard to show that Cauchy sequences under pointwise addition and multiplication form a ring. One can also define null sequences as sequences of elements of D such that | an | converges to zero. Null sequences are a prime ideal in the ring of Cauchy sequences, and the quotient ring is therefore an integral domain. The domain D is embedded in this quotient ring, called the completion of D with respect to the absolute value | x |.

Since fields are integral domains, this is also a construction for the completion of a field with respect to an absolute value. To show that the result is a field, and not just an integral domain, we can either show that null sequences form a maximal ideal, or else construct the inverse directly. The latter can be easily done by taking, for all nonzero elements of the quotient ring, a sequence starting from a point beyond the last zero element of the sequence. Any nonzero element of the quotient ring will differ by a null sequence from such a sequence, and by taking pointwise inversion we can find a representative inverse element.

Another theorem of Alexander Ostrowski has it that any field complete with respect to an Archimedean absolute value is isomorphic to either the real or the complex numbers and the valuation is equivalent to the usual one.[4] The Gelfand-Tornheim theorem states that any field with an Archimedean valuation is isomorphic to a subfield of C, the valuation being equivalent to the usual absolute value on C.[5]

Fields and integral domains

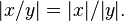

If D is an integral domain with absolute value | x |, then we may extend the definition of the absolute value to the field of fractions of D by setting

On the other hand, if F is a field with ultrametric absolute value | x |, then the set of elements of F such that | x | ≤ 1 defines a valuation ring, which is a subring D of F such that for every nonzero element x of F, at least one of x or x−1 belongs to D. Since F is a field, D has no zero divisors and is an integral domain. It has a unique maximal ideal consisting of all x such that | x | < 1, and is therefore a local ring.

References

- ↑ Koblitz, Neal (1984). P-adic numbers, p-adic analysis, and zeta-functions (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-387-96017-3. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

The metrics we'll be dealing with will come from norms on the field F...

- ↑ Koblitz, Neal (1984). P-adic numbers, p-adic analysis, and zeta-functions (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-387-96017-3. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

By the 'trivial' norm we mean the norm ‖ ‖ such that ‖0‖ = 0 and ‖x‖ = 1 for x ≠ 0.

- ↑ Cassels (1986) p.16

- ↑ Cassels (1986) p.33

- ↑ http://modular.fas.harvard.edu/papers/ant/html/node60.html

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1972). Commutative Algebra. Addison-Wesley.

- Cassels, J.W.S. (1986). Local Fields. London Mathematical Society Student Texts 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31525-5. Zbl 0595.12006.

- Jacobson, Nathan (1989). Basic algebra II (2nd ed.). W H Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1933-9. Chapter 9, paragraph 1 "Absolute values".

- Janusz, Gerald J. (1996–1997). Algebraic Number Fields (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-0429-4.