List of placename renaming in Zimbabwe

Place names in Zimbabwe, including the name of the country itself, have been altered at various points in history. The name Zimbabwe was officially adopted concurrently with Britain's grant of independence in April 1980. Prior to that point, the country had been called Southern Rhodesia from 1898 to 1964 (or 1980, according to British law), Rhodesia from 1964 to 1979, and Zimbabwe Rhodesia between June and December 1979. Since Zimbabwean independence in 1980, the names of cities, towns, streets and other places have been changed by the government, most prominently in a burst of renaming in 1982.

The Zimbabwean government began renaming cities, towns, streets and other places in 1982, hoping to remove vestiges of British and Rhodesian rule. The capital city, Salisbury, was renamed Harare. Many other place names merely had their spellings altered to better reflect local pronunciation in Shona or Kalanga, as under white rule the spellings officially adopted often coincided with pronunciation in Sindebele. Most major cities and towns were renamed, but some places with an Ndebele majority—such as Bulawayo, the country's second city—were not. Some smaller towns retain their colonial-era names, such as Beitbridge, West Nicholson and Fort Rixon. Street names were changed wholesale, with British-style names, particularly those of colonial figures, being phased out in favour of those of black nationalist leaders, prominently Robert Mugabe, Joshua Nkomo and Jason Moyo.

Name of the country

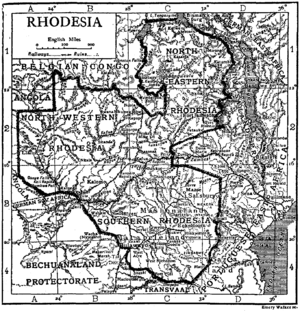

The name of the country has changed several times since it was originally demarcated in the late 19th century by Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company. The company initially referred to each territory it acquired by its respective name—Mashonaland, Matabeleland and so on—and collectively called its lands "Zambesia" (Rhodes' personal preference) or "Charterland" (Leander Starr Jameson's), but neither of these caught on. Most of the first settlers instead called their new home "Rhodesia", after Rhodes; this was common enough usage by 1891 to be used by journalists.[1] In 1892, the Rhodesia Chronicle and Rhodesia Herald newspapers were first published, respectively at Tuli and Salisbury. The company officially applied the name Rhodesia in 1895.[2] "It is not clear why the name should have been pronounced with the emphasis on the second rather than the first syllable," Robert Blake comments, "but this appears to have been the custom from the beginning and it never changed."[1]

Matabeleland and Mashonaland, both of which lay south of the Zambezi, were first officially referred to collectively by Britain as "Southern Rhodesia" in 1898.[1] Southern Rhodesia attained responsible government as a self-governing colony in 1923,[3] while Northern Rhodesia (to the Zambezi's north) became a directly administered British colony the following year.[4]

The name "Zimbabwe", based on a Shona term for Great Zimbabwe, an ancient ruined city in the country's south-east, was first recorded as a term of national reference in 1960, when it was coined by the black nationalist Michael Mawema,[5] whose Zimbabwe National Party became the first to officially use the name in 1961.[6] The term Rhodesia, derived from Rhodes' surname, was perceived as inappropriate because of its colonial origin and connotations.[5] According to Mawema, black nationalists held a meeting in 1960 to choose an alternative name for the country, and the names Machobana and Monomotapa were proposed before his suggestion, Zimbabwe, prevailed.[7] A further alternative, put forward by nationalists in Matabeleland, had been "Matopos", referring to the Matopos Hills to the south of Bulawayo.[6]

It was initially not clear how the chosen term was to be used—a letter written by Mawema in 1961 refers to "Zimbabweland"[6]—but "Zimbabwe" was sufficiently established by 1962 to become the generally preferred term of the black nationalist movement.[5] In a 2001 interview, black nationalist Edson Zvobgo recalled that the name was mentioned by Mawema during a political rally, "and it caught hold, and that was that".[5] The name was subsequently used by the black nationalist factions during the Second Chimurenga campaigns against the Rhodesian government during the Rhodesian Bush War. The most major of these were the Zimbabwe African National Union (led by Robert Mugabe from 1975), and the Zimbabwe African People's Union, led by Joshua Nkomo from its founding in the early 1960s.

When Northern Rhodesia achieved independence as Zambia in 1964, the Southern Rhodesian government introduced a bill to allow the country to be known as just Rhodesia, which passed its third reading on 9 December 1964. Although no assent was given to the bill, the revised name was widely adopted, and following the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965 it was the name of the unrecognised government.[8] This name was used until June 1979, when new institutions of government came into power following the Internal Settlement of the previous year. The country adopted the name Zimbabwe Rhodesia. Following the terms of the Lancaster House Agreement of December 1979 that the United Kingdom should preside over fresh elections before granting independence, direct British control started that month with reversion to the former name of Southern Rhodesia. Britain granted independence under the name Zimbabwe on 18 April 1980.[9]

Geographical renaming since 1980

Starting in 1982, on the second anniversary of the country's independence as Zimbabwe, the government began renaming cities, towns and streets in an attempt to eradicate symbols of British colonialism and white minority rule.[10] The capital Salisbury, which had been named after the British Prime Minister, the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, was renamed Harare, after the Shona chief Neharawa. Other place names were simply new transliterations, to reflect the correct pronunciation in the relevant local language—many places had been denoted with the Sindebele language pronunciation during the colonial period and this generally included the letter "L", which does not exist in Shona. Hence the city of Gwelo became Gweru.

| Pre-1982 name | New name |

|---|---|

| Balla Balla | Mbalabala |

| Belingwe | Mberengwa |

| Chipinga | Chipinge |

| Enkeldoorn | Chivhu |

| Essexvale | Esigodini |

| Fort Victoria | Masvingo |

| Gwelo | Gweru |

| Gatooma | Kadoma |

| Hartley | Chegutu |

| Inyanga | Nyanga |

| Marandellas | Marondera |

| Matopos | Matobo |

| Melsetter | Chimanimani |

| Que Que | Kwekwe |

| Salisbury | Harare |

| Selukwe | Shurugwi |

| Shabani | Zvishavane |

| Sinoia | Chinhoyi |

| Umtali | Mutare |

| Wankie | Hwange |

While most larger cities and towns were renamed, the European spelling of Zimbabwe's second-largest city, Bulawayo, remains unchanged. Other towns which have retained names of European origin include mostly smaller communities such as Beitbridge, Colleen Bawn, West Nicholson, Fort Rixon, Craigmore, Cashel, Juliasdale, Glendale, and Birchenough Bridge. The colonial-era names of suburbs around Harare, such as Borrowdale, Highlands, Rietfontein, Tynwald, and Mount Pleasant also remained unchanged. An exception was Harari, which was renamed Mbare.

Street names were also changed, with names of British colonists such as Cecil Rhodes being replaced with those of Zimbabwean nationalist leaders, such as Jason Moyo, Josiah Tongogara, Simon Muzenda, and Leopold Takawira. Robert Mugabe's name eventually became attached to the main street or town centre of every sizeable town as a result of a spate of changes in 1990. Other streets have been named after leaders of neighbouring countries, such as Samora Machel of Mozambique, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia and Nelson Mandela of South Africa. Others have a general pan-African nationalist theme, such as Africa Unity Square in Harare, formerly Cecil Square.

While these changes have had general acceptance, except among some whites, a more controversial practice has been the recent renaming of schools after Robert Mugabe, prompting accusations of a personality cult.

References

- 1 2 3 Blake, Robert (1977). A History of Rhodesia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 114. ISBN 0-394-48068-6.

- ↑ Brelsford, W. V., ed. (1954). "First Records—No. 6. The Name 'Rhodesia'". The Northern Rhodesia Journal (Lusaka: Northern Rhodesia Society) II (4): 101–102. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Berlyn, Phillippa (April 1978). The Quiet Man: A Biography of the Hon. Ian Douglas Smith. Salisbury: M. O. Collins. pp. 103–104. OCLC 4282978.

- ↑ Gann, Lewis H. (1969) [1964]. A History of Northern Rhodesia: Early Days to 1953. New York: Humanities Press. pp. 191–192. OCLC 46853.

- 1 2 3 4 Fontein, Joost (September 2006). The Silence of Great Zimbabwe: Contested Landscapes and the Power of Heritage (First ed.). London: University College London Press. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-1844721238.

- 1 2 3 Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Sabelo J. (2009). Do 'Zimbabweans' Exist? Trajectories of Nationalism, National Identity Formation and Crisis in a Postcolonial State (First ed.). Bern: Peter Lang AG. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-3-03911-941-7.

- ↑ "What's in a Name? Welcome to the 'Republic of Machobana'". Read On (Harare: Training Aids Development Group): 40. 1991.

- ↑ Palley, Claire (1966). The Constitutional History and Law of Southern Rhodesia 1888–1965, with Special Reference to Imperial Control (First ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 742–743. OCLC 406157.

- ↑ Wessels, Hannes (July 2010). P. K. van der Byl: African Statesman. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-920143-49-7.

- ↑ "Names (Alteration) Act" (PDF). parlzim.gov.zw. Harare: Parliament of Zimbabwe. 1982.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||