Georgette Heyer

| Georgette Heyer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

16 August 1902 Wimbledon, London, UK |

| Died |

4 July 1974 (aged 71) London, UK |

| Pen name |

Georgette Heyer, Stella Martin[1] |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 1921–74 |

| Genre | Historical romance, detective fiction |

| Spouse | George Ronald Rougier (1925–74; her death) |

Georgette Heyer /ˈheɪ.ər/ (16 August 1902 – 4 July 1974) was an English historical romance and detective fiction novelist. Her writing career began in 1921, when she turned a story for her younger brother into the novel The Black Moth. In 1925 Heyer married George Ronald Rougier, a mining engineer. The couple spent several years living in Tanganyika Territory and Macedonia before returning to England in 1929. After her novel These Old Shades became popular despite its release during the General Strike, Heyer determined that publicity was not necessary for good sales. For the rest of her life, she refused to grant interviews, telling a friend: "My private life concerns no one but myself and my family."[2]

Heyer essentially established the historical romance genre and its subgenre Regency romance. Her Regencies were inspired by Jane Austen, but unlike Austen, who wrote about and for the times in which she lived, Heyer was forced to include copious information about the period so that her readers would understand the setting. To ensure accuracy, Heyer collected reference works and kept detailed notes on all aspects of Regency life. While some critics thought the novels were too detailed, others considered the level of detail to be Heyer's greatest asset. Her meticulous nature was also evident in her historical novels; Heyer even recreated William the Conqueror's crossing into England for her novel The Conqueror.

Beginning in 1932, Heyer released one romance novel and one thriller each year. Her husband often provided basic outlines for the plots of her thrillers, leaving Heyer to develop character relationships and dialogue so as to bring the story to life. Although many critics describe Heyer's detective novels as unoriginal, others such as Nancy Wingate praise them "for their wit and comedy as well as for their well-woven plots".[3]

Her success was sometimes clouded by problems with tax inspectors and alleged plagiarists. Heyer chose not to file lawsuits against the suspected literary thieves, but tried multiple ways of minimizing her tax liability. Forced to put aside the works she called her "magnum opus" (a trilogy covering the House of Lancaster) to write more commercially successful works, Heyer eventually created a limited liability company to administer the rights to her novels. She was accused several times of providing an overly large salary for herself, and in 1966 she sold the company and the rights to seventeen of her novels to Booker-McConnell. Heyer continued writing until her death in July 1974. At that time, 48 of her novels were still in print; her last book, My Lord John, was published posthumously.

Early years

Heyer was born in Wimbledon, London, in 1902. She was named after her father, George Heyer.[4] Her mother, Sylvia Watkins, studied both cello and piano and was one of the top three students in her class at the Royal College of Music. Heyer's paternal grandfather had emigrated from Russia, while her maternal grandparents owned tugboats on the River Thames.[5]

Heyer was the eldest of three children; her brothers George Boris (known as Boris) and Frank were four and nine years younger than her.[4] For part of her childhood, the family lived in Paris, France, but they returned to England shortly after World War I broke out in 1914.[6] Although the family's surname had been pronounced "higher", the advent of war led her father to switch to the pronunciation "hair" so they would not be mistaken for Germans.[7] During the war, her father served as a requisitions officer for the British Army in France. After the war ended he was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).[8] He left the army in 1920 with the rank of captain,[9] taught at King's College London and sometimes wrote for The Granta.[4][5]

George Heyer strongly encouraged his children to read and never forbade any book. Georgette read widely and often met with her friends Joanna Cannan and Carola Oman to discuss books.[10] Heyer and Oman later shared their works-in-progress with each other and offered criticism.[11]

When she was 17, Heyer began a serial story to amuse her brother Boris, who suffered from a form of haemophilia and was often weak. Her father enjoyed listening to her story and asked her to prepare it for publication. His agent found a publisher for her book, and The Black Moth, about the adventures of a young man who took responsibility for his brother's card-cheating, was released in 1921.[10][12] According to her biographer Jane Aiken Hodge, the novel contained many of the elements that would become standard for Heyer's novels, the "saturnine male lead, the marriage in danger, the extravagant wife, and the group of idle, entertaining young men".[13] The following year one of her contemporary short stories, "A Proposal to Cicely", was published in Happy Magazine.[14]

Marriage

While holidaying with her family in December 1920, Heyer met George Ronald Rougier, who was two years her senior.[15] The two became regular dance partners while Rougier studied at the Royal School of Mines to become a mining engineer. In the spring of 1925, shortly after the publication of her fifth novel, they became engaged. One month later, Heyer's father died of a heart attack. He left no pension, and Heyer assumed financial responsibility for her brothers, aged 19 and 14.[16] Two months after her father's death, on 18 August, Heyer and Rougier married in a simple ceremony.[17]

In October 1925 Rougier was sent to work in the Caucasus Mountains, partly because he had learned Russian as a child.[18][19] Heyer remained at home and continued to write.[18] In 1926, she released These Old Shades, in which the Duke of Avon courts his own ward. Unlike her first novel, These Old Shades focused more on personal relationships than on adventure.[12] The book appeared in the midst of the 1926 United Kingdom general strike; as a result, the novel received no newspaper coverage, reviews, or advertising. Nevertheless, the book sold 190,000 copies.[20] Because the lack of publicity had not harmed the novel's sales, Heyer refused for the rest of her life to promote her books, even though her publishers often asked her to give interviews.[21] She once wrote to a friend that "as for being photographed at Work or in my Old World Garden, that is the type of publicity which I find nauseating and quite unnecessary. My private life concerns no one but myself and my family."[2]

Rougier returned home in the summer of 1926, but within months he was sent to the East African territory of Tanganyika. Heyer joined him there the following year.[22] They lived in a hut made of elephant grass located in the bush;[11] Heyer was the first white woman her servants had ever seen.[22] While in Tanganyika, Heyer wrote The Masqueraders; set in 1745, the book follows the romantic adventures of siblings who pretend to be of the opposite sex in order to protect their family, all former Jacobites. Although Heyer did not have access to all of her reference material, the book contained only one anachronism: she placed the opening of White's a year too early.[11] She also wrote an account of her adventures, titled "The Horned Beast of Africa", which was published in 1929 in the newspaper The Sphere.[23]

In 1928, Heyer followed her husband to Macedonia, where she almost died after a dentist improperly administered an anaesthetic.[22] She insisted they return to England before starting a family. The following year Rougier left his job, making Heyer the primary breadwinner.[22][24] After a failed experiment running a gas, coke, and lighting company, Rougier purchased a sports shop in Horsham with money they borrowed from Heyer's aunts. Heyer's brother Boris lived above the shop and helped Rougier, while Heyer continued to provide the bulk of the family's earnings with her writing.[22]

Regency romances

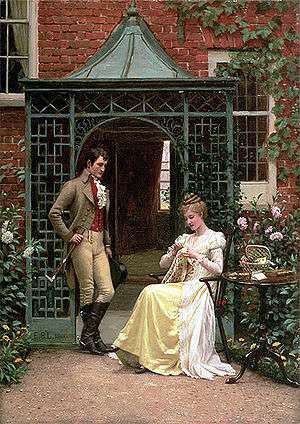

Heyer's earliest works were romance novels, most set before 1800.[25] In 1935, she released Regency Buck, her first novel set in the Regency period. This bestselling novel essentially established the genre of Regency romance.[26] Unlike other romance novels of the period, Heyer's novels used the setting as a plot device. Many of her characters exhibited modern-day sensibilities; more conventional characters in the novels would point out the heroine's eccentricities, such as wanting to marry for love.[27] The books were set almost entirely in the world of the wealthy upper class[28] and only occasionally mention poverty, religion, or politics.[29]

Although the British Regency lasted only from 1811 to 1820, Heyer's romances were set between 1752 and 1825. As noted by literary critic Kay Mussell, the books revolved around a "structured social ritual — the marriage market represented by the London season" where "all are in danger of ostracism for inappropriate behavior".[30] Her Regency romances were inspired by the writings of Jane Austen, whose novels were set in the same era. Austen's works, however, were contemporary novels, describing the times in which she lived. According to Pamela Regis in her work A Natural History of the Romance Novel, because Heyer's stories took place amidst events that had occurred over 100 years earlier, she had to include more detail on the period in order for her readers to understand it.[31] While Austen could ignore the "minutiae of dress and decor",[32] Heyer included those details "to invest the novels ... with 'the tone of the time'".[33] Later reviewers, such as Lillian Robinson, criticized Heyer's "passion for the specific fact without concern for its significance",[34] and Marghanita Laski pointed out that "these aspects on which Heyer is so dependent for her creation of atmosphere are just those which Jane Austen ... referred to only when she wanted to show that a character was vulgar or ridiculous".[35] Others, including A. S. Byatt, believe that Heyer's "awareness of this atmosphere — both of the minute details of the social pursuits of her leisured classes and of the emotional structure behind the fiction it produced — is her greatest asset".[36]

Determined to make her novels as accurate as possible, Heyer collected reference works and research materials to use while writing.[37] At the time of her death she owned over 1,000 historical reference books, including Debrett's and an 1808 dictionary of the House of Lords. In addition to the standard historical works about the medieval and eighteenth-century periods, her library included histories of snuff boxes, sign posts, and costumes.[38] She often clipped illustrations from magazine articles and jotted down interesting vocabulary or facts onto note cards, but rarely recorded where she found the information.[39] Her notes were sorted into categories, such as Beauty, Colours, Dress, Hats, Household, Prices, and Shops; and even included details such as the cost of candles in a particular year.[38][40] Other notebooks contained lists of phrases, covering such topics as "Food and Crockery", "Endearments", and "Forms of Address."[40] One of her publishers, Max Reinhardt, once attempted to offer editorial suggestions about the language in one of her books but was promptly informed by a member of his staff that no one in England knew more about Regency language than Heyer.[41]

In the interests of accuracy, Heyer once purchased a letter written by the Duke of Wellington so that she could precisely employ his style of writing.[42] She claimed that every word attributed to Wellington in An Infamous Army was actually spoken or written by him in real life.[43] Her knowledge of the period was so extensive that Heyer rarely mentioned dates explicitly in her books; instead, she situated the story by casually referring to major and minor events of the time.[44]

Thrillers

In 1931, Heyer released The Conqueror, her first novel of historical fiction to give a fictionalized account of real historical events. She researched the life of William the Conqueror thoroughly, even travelling the route that William took when crossing into England.[45] The following year, Heyer's writing took an even more drastic departure from her early historical romances when she released her first thriller, Footsteps in the Dark. The novel's publication coincided with the birth of her only child, Richard George Rougier, whom she called her "most notable (indeed peerless) work".[46] Later in her life, Heyer requested that her publishers refrain from reprinting Footsteps in the Dark, saying "This work, published simultaneously with my son ... was the first of my thrillers and was perpetuated while I was, as any Regency character would have said, increasing. One husband and two ribald brothers all had fingers in it, and I do not claim it as a Major Work."[47]

For the next several years Heyer published one romance novel and one thriller each year. The romances were far more popular: they usually sold 115,000 copies, while her thrillers sold 16,000 copies.[48] According to her son, Heyer "regarded the writing of mystery stories rather as we would regard tackling a crossword puzzle – an intellectual diversion before the harder tasks of life have to be faced".[25] Heyer's husband was involved in much of her writing. He often read the proofs of her historical romances to catch any errors that she might have missed, and served as a collaborator for her thrillers. He provided the plots of the detective stories, describing the actions of characters "A" and "B".[49] Heyer would then create the characters and the relationships between them and bring the plot points to life. She found it difficult at times to rely on someone else's plots; on at least one occasion, before writing the last chapter of a book, she asked Rougier to explain once again how the murder was really committed.[49]

Her detective stories, which, according to critic Earl F. Bargainnier, "specialize[d] in upper-class family murders", were known primarily for their comedy, melodrama, and romance.[50] The comedy derived not from the action but from the personalities and dialogue of the characters.[51] In most of these novels, all set in the time they were written,[52] the focus relied primarily on the hero, with a lesser role for the heroine.[53] Her early mystery novels often featured athletic heroes; once Heyer's husband began pursuing his lifelong dream of becoming a barrister, the novels began to feature solicitors and barristers in lead roles.[54]

In 1935, Heyer's thrillers began following a pair of detectives named Superintendent Hannasyde and Sergeant (later Inspector) Hemingway. The two were never as popular as other contemporary fictional detectives such as Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot and Dorothy L. Sayers's Lord Peter Wimsey.[55] One of the books featuring Heyer's characters, Death in the Stocks, was dramatized in New York City in 1937 as Merely Murder. The play focused on the comedy rather than the mystery,[56] and it closed after three nights.[37]

According to critic Nancy Wingate, Heyer's detective novels, the last written in 1953,[57] often featured unoriginal methods, motives, and characters, with seven of them using inheritance as the motive.[3] The novels were always set in London, a small village, or at a houseparty.[58] Critic Erik Routley labelled many of her characters clichés, including the uneducated policeman, an exotic Spanish dancer, and a country vicar with a neurotic wife. In one of her novels, the characters' surnames were even in alphabetical order according to the order they were introduced.[59] According to Wingate, Heyer's detective stories, like many of the others of the time, exhibited a distinct snobbery towards foreigners and the lower classes.[60] Her middle-class men were often crude and stupid, while the women were either incredibly practical or exhibited poor judgement, usually using poor grammar that could become vicious.[61] Despite the stereotypes, however, Routley maintains that Heyer had "a quite remarkable gift for reproducing the brittle and ironic conversation of the upper middle class Englishwoman of that age (immediately before 1940)".[59] Wingate further mentions that Heyer's thrillers were known "for their wit and comedy as well as for their well-woven plots".[3]

Financial problems

In 1939, Rougier was called to the Bar, and the family moved first to Brighton, then to Hove, so that Rougier could easily commute to London. The following year, they sent their son to a preparatory school, creating an additional expense for Heyer. The Blitz bombing of 1940–41 disrupted train travel in Britain, prompting Heyer and her family to move to London in 1942 so that Rougier would be closer to his work.

After having lunch with a representative from Hodder & Stoughton, who published her detective stories, Heyer felt that her host had patronized her. The company had an option on her next book; to make them break her contract,[62] she wrote Penhallow, which the 1944 Book Review Digest described as "a murder story but not a mystery story".[63] Hodder & Stoughton turned the book down, thus ending their association with Heyer, and Heinemann agreed to publish it instead. Her publisher in the United States, Doubleday, also disliked the book and ended their relationship with Heyer after its publication.[62]

During World War II, her brothers served in the armed forces, alleviating one of her monetary worries. Her husband, meanwhile, served in the Home Guard, besides continuing as a barrister.[64] As he was new to his career, Rougier did not earn much money, and paper rationing during the war caused lower sales of Heyer's books. To meet their expenses Heyer sold the Commonwealth rights for These Old Shades, Devil's Cub, and Regency Buck to her publisher, Heinemann, for £750. A contact at the publishing house, her close friend A.S. Frere, later offered to return the rights to her for the same amount of money she was paid. Heyer refused to accept the deal, explaining that she had given her word to transfer the rights.[65] Heyer also reviewed books for Heinemann, earning 2 guineas for each review,[66] and she allowed her novels to be serialized in Women's Journal prior to their publication as hardcover books. The appearance of a Heyer novel usually caused the magazine to sell out completely, but she complained that they "always like[d] my worst work".[21]

To minimize her tax liability, Heyer formed a limited liability company called Heron Enterprises around 1950. Royalties from new titles would be paid to the company, which would then furnish Heyer's salary and pay directors' fees to her family. She would continue to receive royalties from her previous titles, and foreign royalties – except for those from the United States – would go to her mother.[67] Within several years, however, a tax inspector found that Heyer was withdrawing too much money from the company. The inspector considered the extra funds as undisclosed dividends, meaning that she owed an additional £3,000 in taxes. To pay the tax bill, Heyer wrote two articles, "Books about the Brontës" and "How to be a Literary Writer", that were published in the magazine Punch.[23][68] She once wrote to a friend, "I'm getting so tired of writing books for the benefit of the Treasury and I can't tell you how utterly I resent the squandering of my money on such fatuous things as Education and Making Life Easy and Luxurious for So-Called Workers."[69]

In 1950, Heyer began working on what she called "the magnum opus of my latter years", a medieval trilogy intended to cover the House of Lancaster between 1393 and 1435.[70] She estimated that she would need five years to complete the works. Her impatient readers continually clamored for new books; to satisfy them and her tax liabilities, Heyer interrupted herself to write Regency romances. The manuscript of volume one of the series, My Lord John, was published posthumously.[70]

The limited liability company continued to vex Heyer, and in 1966, after tax inspectors found that she owed the company £20,000, she finally fired her accountants. She then asked that the rights to her newest book, Black Sheep, be issued to her personally.[71] Unlike her other novels, Black Sheep did not focus on members of the aristocracy. Instead, it followed "the moneyed middle class", with finance a dominant theme in the novel.[72]

Heyer's new accountants urged her to abandon Heron Enterprises; after two years, she finally agreed to sell the company to Booker-McConnell, which already owned the rights to the estates of novelists Ian Fleming and Agatha Christie. Booker-McConnell paid her approximately £85,000 for the rights to the 17 Heyer titles owned by the company. This amount was taxed at the lower capital transfer rate, rather than the higher income tax rate.[73]

Imitators

As Heyer's popularity increased, other authors began to imitate her style. In May 1950, one of her readers notified her that Barbara Cartland had written several novels in a style similar to Heyer's, reusing names, character traits and plot points and paraphrased descriptions from her books, particularly A Hazard of Hearts, which borrowed characters from Friday's Child, and The Knave of Hearts which took off These Old Shades. Heyer completed a detailed analysis of the alleged plagiarisms for her solicitors, and while the case never came to court and no apology was received, the copying ceased.[74] Her lawyers suggested that she leak the copying to the press. Heyer refused.[75]

In 1961, another reader wrote of similarities found in the works of Kathleen Lindsay, particularly the novel Winsome Lass.[76] The novels borrowed plot points, characters, surnames, and plentiful Regency slang. After fans accused Heyer of "publishing shoddy stuff under a pseudonym", Heyer wrote to the other publisher to complain.[77] When the author took exception the accusations, Heyer made a thorough list of the borrowings and historical mistakes in the books. Among these were repeated use of the phrase "to make a cake of oneself", which Heyer had discovered in a privately printed memoir unavailable to the public. In another case, the author referenced a historical incident that Heyer had invented in an earlier novel.[77] Heyer's lawyers recommended an injunction, but she ultimately decided not to sue.[76]

Later years

In 1959, Rougier became a Queen's Counsel.[78] The following year, their son Richard fell in love with the estranged wife of an acquaintance. Richard assisted the woman, Susanna Flint, in leaving her husband, and the couple married after her divorce was finalized. Heyer was shocked at the impropriety but soon came to love her daughter-in-law, later describing her as "the daughter we never had and thought we didn't want".[79] Richard and his wife raised her two sons from her first marriage and provided Heyer with her only biological grandchild in 1966, when their son Nicholas Rougier was born.[71]

As Heyer aged she began to suffer more frequent health problems. In June 1964, she underwent surgery to remove a kidney stone. Although the doctors initially predicted a six-week recovery, after two months they predicted that it might be a year or longer before she felt completely well. The following year, she suffered a mosquito bite which turned septic, prompting the doctors to offer skin grafts.[80] In July 1973 she suffered a slight stroke and spent three weeks in a nursing home. When her brother Boris died later that year, Heyer was too ill to travel to his funeral. She suffered another stroke in February 1974. Three months later, she was diagnosed with lung cancer, which her biographer attributed to the 60–80 cork-tipped cigarettes that Heyer smoked each day (although she said she did not inhale). On 4 July 1974, Heyer died. Her fans learned her married name for the first time from her obituaries.[81]

Legacy

Besides her success in the United Kingdom, Heyer's novels were very popular in the United States and Germany and achieved respectable sales in Czechoslovakia.[82] A first printing of one of her novels in the Commonwealth often consisted of 65,000–75,000 copies,[83] and her novels collectively sold over 100,000 copies in hardback each year.[82] Her paperbacks usually sold over 500,000 copies each.[84] At the time of her death 48 of her books were still in print, including her first novel, The Black Moth.[85]

Her books were very popular during the Great Depression and World War II. Her novels, which journalist Lesley McDowell described as containing "derring-do, dashing blades, and maids in peril", allowed readers to escape from the mundane and difficult elements of their lives.[26] In a letter describing her novel Friday's Child, Heyer commented, "'I think myself I ought to be shot for writing such nonsense. ... But it's unquestionably good escapist literature and I think I should rather like it if I were sitting in an air-raid shelter or recovering from flu."[26]

Heyer essentially invented the historical romance[86] and created the subgenre of the Regency romance.[31] When first released as mass market paperbacks in the United States in 1966, her novels were described as being "in the tradition of Jane Austen".[32] As other novelists began to imitate her style and continue to develop the Regency romance, their novels have been described as "following in the romantic tradition of Georgette Heyer".[32] According to Kay Mussell, "virtually every Regency writer covets [that] accolade".[87]

Heyer has been criticised for anti-semitism, in particular a scene in The Grand Sophy (published in 1950).[88] Her biographers confirm she held bigoted opinions.[89] This was not a regular theme of her writing however.

Despite her popularity and success, Heyer was ignored by critics. Although none of her novels was ever reviewed in a serious newspaper,[84] according to Duff Hart-Davis, "the absence of long or serious reviews never worried her. What mattered was the fact that her stories sold in ever-increasing numbers".[85] Heyer was also overlooked by the Encyclopædia Britannica. The 1974 edition of the encyclopædia, published shortly after her death, included entries on popular writers Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers, but did not mention Heyer.[90] Biographies of Heyer have been published by Jane Aiken Hodge in 1984 and by Jennifer Kloester in 2011.

See also

| Library resources about Georgette Heyer |

| By Georgette Heyer |

|---|

Footnotes

- ↑ Joseph McAleer (1999), Passion's Fortune, Oxford University Press, p. 43, ISBN 978-0-19-820455-8

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Wingate (1976), p. 307.

- 1 2 3 Hodge (1984), p. 13.

- 1 2 Byatt (1975), p. 291.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 15.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p .14.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31684. p. 15455. 9 December 1919. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31897. p. 5452. 11 May 1920. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Byatt (1975), p. 293.

- 1 2 Hughes (1993), p. 38.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 17.

- ↑ Fahnestock-Thomas (2001), p. 3.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 21.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 22.

- ↑ Hodge (194), p. 23.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 27.

- ↑ Byatt (1975), p. 292.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 25.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 69.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hodge (1984), pp. 27–30.

- 1 2 Fahnestock-Thomas (2001), p. 4.

- ↑ Byatt (1975), p. 294.

- 1 2 Devlin (1984), p. 361.

- 1 2 3 McDowell, Lesley (11 January 2004), "Cads wanted for taming; Hold on to your bodices: Dorothy L. Sayers and Georgette Heyer are making a comeback this year. Lesley McDowell can't wait.", The Independent on Sunday (London), p. 17

- ↑ Regis (2003), p. 127.

- ↑ Laski (1970), p. 283.

- ↑ Laski (1970), p. 285.

- ↑ Mussell (1984), p. 413.

- 1 2 Regis (2003), pp. 125–126.

- 1 2 3 Robinson (1978), p. 322.

- ↑ Robinson (1978), p. 323.

- ↑ Robinson (1978), p. 326.

- ↑ Laski (1970), p. 284.

- ↑ Byatt (1969), p. 275.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 43.

- 1 2 Byatt (1975), p. 300.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 43, 46.

- 1 2 Byatt (1975), p. 301.

- ↑ Byatt (1975), p. 298.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 53.

- ↑ Byatt (1969), p. 276.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 71.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 31.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 35.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 102.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 38.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 40.

- ↑ Bargainnier (1982), pp. 342, 343.

- ↑ Bargainnier (1982), p. 352.

- ↑ Devlin (1984), p. 360.

- ↑ Bargainnier (1982), p. 350.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 36.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 42.

- ↑ Devlin (1984), p. 371.

- ↑ Wingate (1976), p. 311.

- ↑ Wingate (1976), p. 308.

- 1 2 Routley (1972), pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Wingate (1976), p. 309.

- ↑ Robinson (1978), pp. 330–331.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 63.

- ↑ 1944 Book Review Digest, p. 374.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 56, 57, 61.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 61, 62.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 90.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 106.

- ↑ Byatt (1975), p. 302.

- 1 2 Devlin (1984), p. 390.

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), p. 169.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 174.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Kloester (2012) pp. 275-9

- ↑ Hodge (1984), p. 206.

- 1 2 Kloester (2012), pp. 335-336

- 1 2 Hodge (1984), pp. 140–141.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 41676. p. 2264. 7 April 1959. Retrieved 2008-04-10.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 141, 151.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 163, 165.

- ↑ Hodge (1984), pp. 175, 204–206.

- 1 2 Hebert (1974), pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Reinhardt (1974), pp. 257–258.

- 1 2 Byatt (1975), p. 297.

- 1 2 Hart-Davis (1974), pp. 258–259.

- ↑ A historical romance is a romance novel set in the past. This is not to be confused with historical fiction that was influenced by romanticism.

- ↑ Mussell (1984), p. 412.

- ↑ http://www.tor.com/2013/05/28/regency-manipulations-the-grand-sophy/

- ↑ http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/of-froth-and-ferocity-20120106-1po2h.html

- ↑ Fahnestock-Thomas (2001), p. 261.

References

- "Georgette Heyer: Penhallow", 1944 Book Review Digest, H.W. Wilson Co, 1944

- Bargainnier, Earl F. (Fall–Winter 1982), "The Dozen Mysteries of Georgette Heyer", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 341–355, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Byatt, A. S. (August 1969), "Georgette Heyer Is a Better Novelist Than You Think", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, AL: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 270–277, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Byatt, A. S. (5 October 1975), "The Ferocious Reticence of Georgette Heyer", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, AL: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 289–303, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Devlin, James P. (Summer 1984) [in The Armchair Detective], "The Mysteries of Georgette Heyer: A Janeite's Life of Crime", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, AL: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 359–394, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary (2001), Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Hart-Davis, Duff (7 July 1974), "20th Century Jane Austen", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 258–259, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Hebert, Hugh (6 July 1974), "Post Script", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 254–255, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Hodge, Jane Aiken (1984), The Private World of Georgette Heyer, London: The Bodley Head, ISBN 0-09-949349-7

- Hughes, Helen (1993), The Historical Romance, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-05812-0

- Kloester, Jennifer (2012). Georgette Heyer: Biography of a Bestseller. London: William Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-434-02071-3

- Laski, Marghanita (1 October 1970), "Post The Appeal of Georgette Heyer", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, AL: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 283–286, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Mussell, Kay (1984), "Fantasy and Reconciliation", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 412–417, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Regis, Pamela (2003), A Natural History of the Romance Novel, Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-3303-4

- Reinhardt, Max (12 July 1974), "Georgette Heyer", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 257–258, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Robinson, Lillian S. (1978), "On Reading Trash", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 321–335, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Routley, Erik (1972), "The Puritan Pleasures of the Detective Story", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 286–287, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

- Wingate, Nancy (April 1976), "Georgette Heyer: a Reappraisal", in Fahnestock-Thomas, Mary, Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, Saraland, Alabama: Prinnyworld Press (published 2001), pp. 305–321, ISBN 978-0-9668005-3-1

Further reading

- Chris, Teresa (1989). Georgette Heyer's Regency England. Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd, ISBN 0-283-99832-6

- Kloester, Jennifer (2005). Georgette Heyer's Regency World. London: Heinemann, ISBN 0-434-01329-3

External links

| Library resources about Georgette Heyer |

| By Georgette Heyer |

|---|

- Georgette Heyer website

- Notes on 2009 Heyer conference

- Works by Georgette Heyer at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Georgette Heyer at Internet Archive

- Works by Georgette Heyer at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| ||||||||||

|