Pipe network analysis

In fluid dynamics, pipe network analysis is the analysis of the fluid flow through a hydraulics network, containing several or many interconnected branches. The aim is to determine the flow rates and pressure drops in the individual sections of the network. This is a common problem in hydraulic design.

Description

To direct water to many individuals, municipal water supplies often route it through a water supply network. A major part of this network may consist of interconnected pipes. This network creates a special class of problems in hydraulic design, with solution methods typically referred to as pipe network analysis. The modern tool for this is specialized software that automatically solves the problems. However, the problems can also be addressed with simpler methods, like a spreadsheet equipped with a solver, or a modern graphing calculator.

Network analysis

Once the friction factors are solved for, then we can start considering the network problem. We can solve the network by satisfying two conditions.

- At any junction, the flow into a junction equals the flow out of the junction.

- Between any two junctions, the head loss is independent of the path taken.

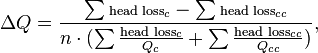

The classical approach for solving these networks is to use the Hardy Cross method. In this formulation, first you go through and create guess values for the flows in the network. That is, if Q7 enters a junction and Q6 and Q4 leave the same junction, then the initial guess must satisfy Q7 = Q6 + Q4. After the initial guess is made, then, a loop is considered so that we can evaluate our second condition. Given a starting node, we work our way around the loop in a clockwise fashion, as illustrated by Loop 1. We add up the head losses according to the Darcy–Weisbach equation for each pipe if Q is in the same direction as our loop like Q1, and subtract the head loss if the flow is in the reverse direction, like Q4. To satisfy the second condition, we should end up with 0 about the loop if the network is completely solved. If the actual sum of our head loss is not equal to 0, then we will adjust all the flows in the loop by an amount given by the following formula, where a positive adjustment is in the clockwise direction.

where

- n is 1.85 for Hazen-Williams and

- n is 2 for Darcy–Weisbach.

The clockwise specifier (c) means only the flows that are moving clockwise in our loop, while the counter-clockwise specifier (cc) is only the flows that are moving counter-clockwise.

This adjustment doesn't solve the problem, since most networks have several loops. It is okay to use this adjustment, however, because the flow changes won't alter condition 1, and therefore, the other loops still satisfy condition 1. However, we should use the results from the first loop before we progress to other loops.

The modern method is simply to create a set of conditions from your junctions and head-loss criteria. Then, use a Root-finding algorithm to find Q values that satisfy all the equations. The literal friction loss equations use a term called Q2, but we want to preserve any changes in direction. Create a separate equation for each loop where the head losses are added up, but instead of squaring Q, use |Q|·Q instead (with |Q| the absolute value of Q) for the formulation so that any sign changes reflect appropriately in the resulting head-loss calculation.

See also

References

- N. Hwang, R. Houghtalen, "Fundamentals of hydraulic Engineering Systems" Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. 1996.

- L.F. Moody, "Friction factors for pipe flow," Trans. ASME, vol. 66, 1944.

- C. F. Colebrook, "Turbulent flow in pipes, with particular reference to the transition region between smooth and rough pipe laws," Jour. Ist. Civil Engrs., London (Feb. 1939).