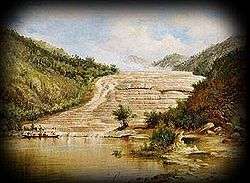

Pink and White Terraces

The Pink Terraces, or Otukapuarangi ("fountain of the clouded sky") in Māori, and the White Terraces, also known as Te Tarata ("the tattooed rock"), were natural wonders of New Zealand.[1] They were lost, and for long after were thought to have been completely destroyed, by the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera, being replaced by the Waimangu Volcanic Rift Valley.

The Terraces were formed by geothermally heated water containing large amounts of silicic acid and sodium chloride from two large geysers. These geysers were part of a group of 40 geysers in the nearby area.

The Pink and the White Terraces were 800 metres apart. The White Terraces were at the north end of Lake Rotomahana and faced away from the lake at the entrance to the Kaiwaka stream. They descended to the lake edge 40 metres below. The extra sunlight they received from facing north gave them a more bleached or white appearance. The Pink Terraces were about two thirds of the way down the lake sheltered from the harsh sun on the western shores, facing south-east. Their pink appearance (near the colour of a rainbow trout) was largely due to less sunlight reaching them and therefore less bleaching.

Formation

The foundations for both terraces were formed from alternate layers of volcanic fallout over a long period of time. The volcanic debris layers, alternating between rhyolitic and sedimentary stone, formed the base for precipitation of silica.

The precipitation formed many pools and steps over time. Precipitation occurred by two methods. The ascending foundation over time formed a lip which would trap the descending flow and become level again. This process formed attractive swimming places, both for the shape and for the warm water. When the thermal layers sloped in the other direction away from the geyser, then silica steps formed on the surface. Both types of formation grew as silica-laden water cascaded over them, and the water also enhanced the spectacle. Geologist Ferdinand von Hochstetter wrote after his visit in 1859 that "doubtless thousands of years were required" for their formation.[2]

The White Terraces were the larger formation, covering 3 hectares and descending over approximately 50 layers and a drop in height of 40 metres. The Pink Terraces descended 30 metres over a distance of 75 metres. The converging Pink Terraces started at the top with a width of 75–100 metres and the bottom layers were approximately 27 metres wide. The Pink Terraces were where people preferred to bathe due to the more suitable pools.[3]

History

One of the first Europeans to visit Rotomahana was Ernst Dieffenbach. He briefly visited Rotomahana and the terraces while on a survey for the New Zealand Company[4] in early June 1841. The description of his visit in his book "Travels in New Zealand" [5] inspired an interest in the Pink and White Terraces by the outside world.

The terraces were New Zealand's most famous tourist attraction, sometimes referred to as the Eighth Wonder of the World. New Zealand was still relatively inaccessible and passage took several months by ship. The journey from Auckland was typically by steamer to Tauranga, the bridle track to Ohinemutu on Lake Rotorua, by coach to Te Wairoa (the home of the missionary the Reverend Seymour Mills Spencer),[6] by canoe across Lake Tarawera, and then on foot over the hill to the swampy shores of Lake Rotomahana and the terraces.[1]

Those that made the journey to the terraces were most frequently well to do overseas tourists or officers from the British forces in New Zealand. The list of notable tourists included Sir George Grey in 1849, Alfred Duke of Edinburgh in 1869, and Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope in 1874.[7]

The appearance of the terraces was fortunately recorded for posterity by a number of photographers but as it was before colour photography was invented their images lack the enticing colour the formations were known for. Several artists drew and painted the terraces before their loss in 1886, most notably Charles Blomfield who visited on more than one occasion. Their atmospheric views are the main record of the Eighth Wonder of the World.

Sophia Hinerangi, sometimes known as Te Paea took over as principal guide from the older Kate Middlemass in the early 1880s, she became recognised as the principal tourist guide of the Pink and White Terraces. Sophia observed the disturbances to Lake Tarawera water levels in the days preceding the eruption.[8]

Lead up to loss

A number of people mapped and commented on the region before the loss of the terraces. Ferdinand von Hochstetter carried out a geographic and geological survey of the Rotomahana lake and area in 1859, producing his Geographic and Geological survey. This gave enough data to form the first map of the area and to suggest how the terraces had been formed.[3]

In 1873 Stephenson Percy Smith climbed Tarawera and gave the impression that the mountain top was rough but showed no sign of volcanic vents. In March 1881 Dr. G. Seelhorst climbed Wahanga dome and the northern end of Ruawahia dome in search of a presumed "falling star" following reports of glowing and smoke from an area behind Wahanga. In 1884 a surveyor named Charles Clayton while surveying described the top of Wahanga dome as volcanic with several depressions, one being approximately 200 feet deep.

Loss

On 10 June 1886, Mount Tarawera erupted. The eruption spread from west of Wahanga dome, 5 kilometres to the north, down to Lake Rotomahana.[9] The volcano belched out hot mud, red hot boulders, and immense clouds of black ash from a 17-kilometre rift that crossed the mountain, passed through the lake, and extended beyond into the Waimangu valley.

After the eruption, a crater over 100 metres deep encompassed the former site of the terraces.[9] After some years this filled with water to form a new Lake Rotomahana, 30 metres higher and much larger than the old lake.[10][11]

Alfred Patchet Warbrick, a boat builder at Te Wairoa, witnessed the eruption of Mount Tarawera from Maunga Makatiti to the north of Lake Tarawera. Warbrick soon had whale boats on lake Tarawera investigating the new landscape; he in time became a significant tourist guide to the post eruption attractions. Warbrick never accepted that the Pink and White Terraces had been totally destroyed.[12]

Rediscovery

The terraces were long thought to have been destroyed around 3 a.m. on 10 June 1886 during the eruption. However, a team including researchers from GNS Science, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and Waikato University were mapping the lake floor when they discovered part of the Pink Terraces in February 2011. The lowest two tiers of the terraces were found in their original place at 60 metres (200 ft) deep (too deep for easy scuba diving).[13][14] A part of the White Terraces was rediscovered in June 2011.[15] The announcement of the rediscovery of the White Terraces coincided with the 125th anniversary of the eruption of Mt. Tarawera in 1886. It is thought that the rest of the terraces may be buried in sediment rather than having been destroyed.

The claims of rediscovery have been challenged by skeptic Bill Keir, who has calculated that the 'rediscovered' structures are not where the terraces were before the eruption. Specifically, the recently discovered structures are 50–60 metres under the lake surface, but the historic terraces are expected to be as little as 10 metres under, and "could not be more than 40 metres below the surface". Keir speculates that the structures discovered by the GNS team are prehistoric terraces, never before seen by humans; or perhaps step-shaped objects created by the eruption.[16]

The WHOI/GNS et al. findings may be reconciled with the Keir estimate, by reference to a 1975 meta-analysis by James Healy. Healy reviewed the 19th-century reports and, with his own 1970 borehole finding...reports the probable range for the terrace bases is 37–47 metres below the present lake level. The remaining variance may be a combination of 19th-century measurement error and/or localised slumping.[17]

Similar places

- Badab-e Surt in Iran

- Mammoth Hot Springs at Yellowstone National Park in the United States

- Pamukkale in Turkey

- Terme di Saturnia in Italy

See also

References

- 1 2 "Pink and White Terraces". Rotorua Museum. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Hochstetter, Ferdinand von (1867). New Zealand : its physical geography, geology, and natural history. Stuttgart: J G Cotta. p. 412.

- 1 2 von Hochstetter, Ferdinand; Petermann, August H. (1864). Geology of New Zealand. T. Delattre.

- ↑ McLintock, A. H., ed. (1966). "Diffenbach, Ernst". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Dieffenbach, Ernest (1843). Travels in New Zealand. John Murray. pp. 382–383.

- ↑ Philip, Andrews (1995). Rotorua Tarawera and The Terraces (2nd ed.). Bibliophil & The Buried Village. ISBN 0-473-03177-9.

- ↑ Bag, Terry (17 August 2007). "Strange Days on Lake Rotomahana: The End of the Pink and White Terraces". White Fungus (7). Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Sophia Hinerangi biography from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography

- 1 2 "Historic volcanic activity: Tarawera". Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ "Mount Tarawera subject guide". Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "The search for the Pink and White Terraces". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Keam, R F. "Warbrick, Alfred Patchett 1860–1940". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ Donnell, Hayden (2 February 2011). "Remains of Pink Terraces discovered". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ "Scientists find part of Pink and White Terraces under Lake Rotomahana". GNS Science. 2 February 2011.

- ↑ "Terrace discovery most surprising yet". One News. 10 June 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Keir, Bill (2014). "The Pink and White Terraces: still lost?". New Zealand Skeptic 110: 7–12.

- ↑ Healy, James (1975). "The gross effect of rainfall on lake levels in the Rotorua district". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 5 (1): 77–100. doi:10.1080/03036758.1975.10419381.

External links

- Images and Paintings of the Pink and White Terraces in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Photos of the Pink & White Terraces

- Map of the Terraces on Te Ara

Coordinates: 38°15′38″S 176°25′50″E / 38.26056°S 176.43056°E