Piedras Negras (Maya site)

Coordinates: 17°10′0″N 91°15′45″W / 17.16667°N 91.26250°W

Piedras Negras is the modern name for a ruined city of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization located on the north bank of the Usumacinta River in the Petén department of northeastern Guatemala.

Etymology

The name Piedras Negras means "black stones" in Spanish. Its name in the language of the Classic Maya has been read in Maya inscriptions as Yo'k'ib', meaning "great gateway" or "entrance",[1] considered a possible reference to a large and now dry sinkhole nearby.[2] Some authors think that the name is Paw Stone, but is more likely to be the name of the founder as hieroglyphs on Throne 1 and altar 4 show.

History of Piedras Negras

Piedras Negras had been populated since the 7th century BC. Its population seems to have peaked twice. The first population peak happened in the Late Preclassic period, around 200 BC, and was followed by a decline.[3] The second population peak of Piedras Negras happened in the Late Classic period, around the second half of the 8th century, during which the maximum population of the principal settlement is estimated to have been around 2,600. At the same time, Piedras Negras was also the largest polity in this region with a total population estimated to be around 50,000.[4]

Piedras Negras was an independent city-state for most of the Early and Late Classic periods, although it was sometimes in alliance with other states of the region and may have paid tribute to others at times. It had an alliance with Yaxchilan, in what is now Chiapas, Mexico, some 40 km up the Usumacinta River. Ceramics show the site was occupied from the mid-7th century BC to 850 AD. Its most impressive period of sculpture and architecture dated from about 608 through 810, although there is some evidence that Piedras Negras was already a city of some importance since 400 AD.

Panel 12 of Piedras Negras shows three neighboring rulers as captives of Ruler C. One of the captives might be the ninth king of Yaxchilan, Joy B'alam (also known as Knot-Eye Jaguar I), who continued to reign after the panel was made. As subservient rulers were often depicted as bound captives even while continuing to rule their own kingdoms, the panel suggests that Piedras Negras may have established its authority over the middle Usumacinta drainage in about 9.4.0.0.0 (514 AD).[5][6]

The artistry of the sculpture of the Late Classic period of Piedras Negras is considered particularly fine. The site has two ball courts and several plazas; there are vaulted palaces and temple pyramids, including one that is connected to one of the many caves in the site. Along the banks of the river is a large boulder with the emblem glyph of Yo’ki’b carved on it, facing skyward.

A unique feature of the monuments at Piedras Negras is the frequent occurrence of the so-called "artists' signatures". Individual artists have been identified by the use of recurring glyphs on stelae and other reliefs.

Ruler 7 (reigned 781-808?) of Piedras Negras was captured by K'inich Tatbu Skull IV of Yaxchilan. This event was recorded on the lintel 10 of Yaxchilan.[7] Piedras Negras might have been abandoned within several years after this event.[8]

Before the site was abandoned, some monuments were deliberately damaged, including images and glyphs of rulers defaced, while other were left intact, suggesting a revolt or conquest by people literate in Maya writing.

List of rulers

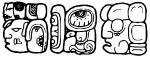

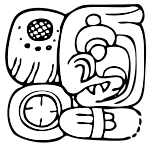

| Name | Glyph | Reigned from | Reigned until | Monuments | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruler A |  |

c. 297 AD[9] | Ruler A was later captured by Moon Skull of Yaxchilan[9] | ||

| Ruler B |  |

c. 478 AD[9] | |||

| Yat Ahk I |  |

c. 510 AD[10] | |||

| Ruler C | June 30, 514 AD[9] | c. 520 AD[10] |

|

||

| K'inich Yo'nal Ahk I |  |

November 14, 603 AD[11] | February 3, 639 AD[11] | Some scholars have argued that K'inich Yo'nal Ahk I refounded the ruling dynasty at Piedras Negras.[13] | |

| Itzam K'an Ahk I |  |

April 12, 639 AD[14] | November 15, 686 AD[14] | ||

| K'inich Yo'nal Ahk II |  |

January 2, 687 AD[15] | c. 729 AD[14][16] | ||

| Itzam K'an Ahk II |  |

November 9, 729 AD[17] | November 26, 757 AD[17] | There is evidence that Itzam K'an Ahk II started a new patriline at Piedras Negras.[18] | |

| Yo'nal Ahk III |  |

March 10, 758 AD[19] | c. 767 AD[19] | ||

| Ha' K'in Xook |  |

February 14, 767 AD[19] | March 24, 780 AD[19] | Appears to have either died or abdicated.[19] Scholars are unsure if March 24, 780 AD refers to Ha' K'in Xook's death date, or rather the date of his burial.[12][19] | |

| K'inich Yat Ahk II |  |

May 31, 781 AD[20] | c. 808 AD[21] | Acceded to the throne almost a year following the death of Ha' K'in Xook. Despite this time gap, there is no evidence to suggest anyone was ruling Piedras Negras in the interim.[22] He was later captured by K'inich Tatbu Skull IV of Yaxchilan.[23] | |

Modern history of the site

The site was first explored, mapped, and its monuments photographed by Teoberto Maler at the end of the 19th century.

An archeological project at Piedras Negras was conducted by the University of Pennsylvania from 1931 to 1939 under the direction of J. Alden Mason and Linton Satterthwaite. Further archaeological work here was conducted from 1997 to 2000, directed by Stephen Houston of Brigham Young University and Hector Escobedo of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, with permission from the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala (IDAEH).

Mayanist Tatiana Proskouriakoff was the first to decipher the names and dates of a Maya dynasty from her work with the monuments at this site, a breakthrough in the decipherment of the Maya Script. Prouskourikoff was buried here in Group F after her death in 1985.

In 2002 the World Monuments Fund earmarked 100,000 United States dollars for the conservation of Piedras Negras. It is today part of Guatemala's Sierra del Lacandón national park.

Notes

- ↑ Martin, Simon and Grube, Nikolai (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 139. ISBN 0-500-05103-8.

- ↑ Ibid. Sinkholes and caves such as this are frequently associated in Maya mythology with entrances to the Underworld or Xibalba.

- ↑ Johnson, Kristopher (2004). "The Application of Pedology, Stable Carbon Isotope Analyses and Geographic Information Systems to Ancient Soil Resource Investigations at Piedras Negras, Guatemala". Scholars Archive. Brigham Young University. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ http://www.famsi.org/research/piedras_negras/pn_project/nelson_thesis.pdf

- ↑ http://decipherment.wordpress.com/2007/08/18/the-captives-on-piedras-negras-panel-12/

- ↑ http://whp.uoregon.edu/DigitalCahuleu/Galleries/Andrews/PattenRubbing/intro.html

- ↑ http://www.peabody.harvard.edu/CMHI/detail.php?num=10&site=Yaxchilan&type=Lintel

- ↑ http://www.mesoweb.com/encyc/view.asp?act=viewexact&view=normal&word=7&wordAND=Piedras+Negras+Ruler

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 140.

- 1 2 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 142.

- ↑ Sharer & Traxler 2005, p. 423.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 145.

- ↑ Martin & Grube 2000, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 148.

- ↑ Martin & Grube 2000, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Martin & Grube 2000, p. 152.

- ↑ Martin & Grube 2000, p. 149.

- ↑ O'Neil 2014, p. 142.

- ↑ Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 152–153.

Bibliography

- Martin, Simon; Grube, Nikolai (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500051030.

- "Piedras Negras, Guatemala". 2003 Nominations. Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- Förstemann, Ernst (1902). "Eine historische Maya-Inschrift". Globus 81 (10): 150–153. ISSN 0935-0535.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piedras Negras, Maya site. |

- Description and Photo Gallery

- Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program (CMHI) of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University