Piano

|

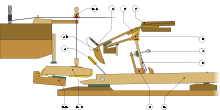

A grand piano (left) and an upright piano (right) | |

| Keyboard instrument | |

|---|---|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification |

314.122-4-8 (Simple chordophone with keyboard sounded by hammers) |

| Inventor(s) | Bartolomeo Cristofori |

| Developed | Early 18th century |

| Playing range | |

| |

The piano (Italian pronunciation: [ˈpjaːno]; an abbreviation of pianoforte [pjanoˈfɔrte]) is a musical instrument played using a keyboard.[1] It is widely employed in classical, jazz, traditional and popular music for solo and ensemble performances, accompaniment, and for composing and rehearsal. Although the piano is not portable and often expensive, its versatility and ubiquity have made it one of the world's most familiar musical instruments.

An acoustic piano usually has a protective wooden case surrounding the soundboard and metal strings, and a row of 88 black and white keys (52 white, 36 black). The strings are sounded when the keys are pressed, and silenced when the keys are released. The note can be sustained, even when the keys are released, by the use of pedals.

Pressing a key on the piano's keyboard causes a padded (often with felt) hammer to strike strings. The hammer rebounds, and the strings continue to vibrate at their resonant frequency.[2] These vibrations are transmitted through a bridge to a soundboard that amplifies by more efficiently coupling the acoustic energy to the air. When the key is released, a damper stops the strings' vibration, ending the sound. Although an acoustic piano has strings, it is usually classified as a percussion instrument because the strings are struck rather than plucked (as with a harpsichord or spinet); in the Hornbostel-Sachs system of instrument classification, pianos are considered chordophones. With technological advances, electric, electronic, and digital pianos have also been developed.

The word piano is a shortened form of pianoforte, the Italian term for the instrument, which in turn derives from gravicembalo col piano e forte[3] and fortepiano. The Italian musical terms piano and forte indicate "soft" and "loud" respectively,[4] in this context referring to the variations in volume produced in response to a pianist's touch on the keys: the greater the velocity of a key press, the greater the force of the hammer hitting the strings, and the louder the sound of the note produced.

History

The piano was founded on earlier technological innovations. The first string instruments with struck strings were the hammered dulcimers.[5] During the Middle Ages, there were several attempts at creating stringed keyboard instruments with struck strings.[6] By the 17th century, the mechanisms of keyboard instruments such as the clavichord and the harpsichord were well known. In a clavichord, the strings are struck by tangents, while in a harpsichord they are plucked by quills. Centuries of work on the mechanism of the harpsichord in particular had shown the most effective ways to construct the case, soundboard, bridge, and keyboard for a mechanism intended to hammer strings.

Invention

The invention of the modern piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, Italy, who was employed by Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, as the Keeper of the Instruments; he was an expert harpsichord maker, and was well acquainted with the body of knowledge on stringed keyboard instruments. It is not known exactly when Cristofori first built a piano. An inventory made by his employers, the Medici family, indicates the existence of a piano by the year 1700; another document of doubtful authenticity indicates a date of 1698. The three Cristofori pianos that survive today date from the 1720s.[7][8]

Cristofori named the instrument un cimbalo di cipresso di piano e forte ("a keyboard of cypress with soft and loud"), abbreviated over time as pianoforte, fortepiano, and simply, piano.[9] While the clavichord allowed expressive control of volume and sustain, it was too quiet for large performances. The harpsichord produced a sufficiently loud sound, but offered little expressive control over each note. The piano offered the best of both, combining loudness with dynamic control.[8]

Cristofori's great success was solving, with no prior example, the fundamental mechanical problem of piano design: the hammer must strike the string, but not remain in contact with it (as a tangent remains in contact with a clavichord string) because this would damp the sound. Moreover, the hammer must return to its rest position without bouncing violently, and it must be possible to repeat a note rapidly. Cristofori's piano action was a model for the many approaches to piano actions that followed. Cristofori's early instruments were made with thin strings, and were much quieter than the modern piano, but much louder and with more sustain in comparison to the clavichord—the only previous keyboard instrument capable of dynamic nuance via the keyboard.

The early fortepiano

Cristofori's new instrument remained relatively unknown until an Italian writer, Scipione Maffei, wrote an enthusiastic article about it in 1711, including a diagram of the mechanism, that was translated into German and widely distributed.[8] Most of the next generation of piano builders started their work due to reading it. One of these builders was Gottfried Silbermann, better known as an organ builder. Silbermann's pianos were virtually direct copies of Cristofori's, with one important addition: Silbermann invented the forerunner of the modern sustain pedal, which lifts all the dampers from the strings simultaneously.

Silbermann showed Johann Sebastian Bach one of his early instruments in the 1730s, but Bach did not like it at that time, claiming that the higher notes were too soft to allow a full dynamic range. Although this earned him some animosity from Silbermann, the criticism was apparently heeded. Bach did approve of a later instrument he saw in 1747, and even served as an agent in selling Silbermann's pianos.[10]

Piano-making flourished during the late 18th century in the Viennese school, which included Johann Andreas Stein (who worked in Augsburg, Germany) and the Viennese makers Nannette Streicher (daughter of Stein) and Anton Walter. Viennese-style pianos were built with wood frames, two strings per note, and had leather-covered hammers. Some of these Viennese pianos had the opposite coloring of modern-day pianos; the natural keys were black and the accidental keys white.[11] It was for such instruments that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed his concertos and sonatas, and replicas of them are built today for use in authentic-instrument performance of his music. The pianos of Mozart's day had a softer, more ethereal tone than today's pianos or English pianos, with less sustaining power. The term fortepiano is now used to distinguish these early instruments from later pianos.

|

Comparison of piano sound

Modern piano sound

The same piece, on a modern piano |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

The modern piano

In the period lasting from about 1790 to 1860, the Mozart-era piano underwent tremendous changes that led to the modern form of the instrument. This revolution was in response to a preference by composers and pianists for a more powerful, sustained piano sound, and made possible by the ongoing Industrial Revolution with resources such as high-quality piano wire for strings, and precision casting for the production of iron frames. Over time, the tonal range of the piano was also increased from the five octaves of Mozart's day to the 7-plus range found on modern pianos.

Early technological progress owed much to the firm of Broadwood. John Broadwood joined with another Scot, Robert Stodart, and a Dutchman, Americus Backers, to design a piano in the harpsichord case—the origin of the "grand". They achieved this in about 1777. They quickly gained a reputation for the splendour and powerful tone of their instruments, with Broadwood constructing ones that were progressively larger, louder, and more robustly constructed. They sent pianos to both Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven, and were the first firm to build pianos with a range of more than five octaves: five octaves and a fifth (interval) during the 1790s, six octaves by 1810 (Beethoven used the extra notes in his later works), and seven octaves by 1820. The Viennese makers similarly followed these trends; however the two schools used different piano actions: Broadwoods were more robust, Viennese instruments were more sensitive.

By the 1820s, the center of innovation had shifted to Paris, where the Pleyel firm manufactured pianos used by Frédéric Chopin and the Érard firm manufactured those used by Franz Liszt. In 1821, Sébastien Érard invented the double escapement action, which incorporated a repetition lever (also called the balancier) that permitted repeating a note even if the key had not yet risen to its maximum vertical position. This facilitated rapid playing of repeated notes, a musical device exploited by Liszt. When the invention became public, as revised by Henri Herz, the double escapement action gradually became standard in grand pianos, and is still incorporated into all grand pianos currently produced.

Other improvements of the mechanism included the use of felt hammer coverings instead of layered leather or cotton. Felt, which was first introduced by Jean-Henri Pape in 1826, was a more consistent material, permitting wider dynamic ranges as hammer weights and string tension increased. The sostenuto pedal (see below), invented in 1844 by Jean-Louis Boisselot and copied by the Steinway firm in 1874, allowed a wider range of effects.

One innovation that helped create the sound of the modern piano was the use of a strong iron frame. Also called the "plate", the iron frame sits atop the soundboard, and serves as the primary bulwark against the force of string tension that can exceed 20 tons in a modern grand. The single piece cast iron frame was patented in 1825 in Boston by Alpheus Babcock,[12] combining the metal hitch pin plate (1821, claimed by Broadwood on behalf of Samuel Hervé) and resisting bars (Thom and Allen, 1820, but also claimed by Broadwood and Érard). Babcock later worked for the Chickering & Mackays firm who patented the first full iron frame for grand pianos in 1843. Composite forged metal frames were preferred by many European makers until the American system was fully adopted by the early 20th century.

The increased structural integrity of the iron frame allowed the use of thicker, tenser, and more numerous strings. In 1834, the Webster & Horsfal firm of Birmingham brought out a form of piano wire made from cast steel; according to Dolge it was "so superior to the iron wire that the English firm soon had a monopoly."[13] But a better steel wire was soon created in 1840 by the Viennese firm of Martin Miller,[13] and a period of innovation and intense competition ensued, with rival brands of piano wire being tested against one another at international competitions, leading ultimately to the modern form of piano wire.[14]

Other important advances included changes to the way the piano is strung, such as the use of a "choir" of three strings rather than two for all but the lowest notes, and the implementation of an over-strung scale, in which the strings are placed in two separate planes, each with its own bridge height. (This is also called cross-stringing. Whereas earlier instruments' bass strings were a mere continuation of a single string plane, over-stringing placed the bass bridge behind and to the treble side of the tenor bridge area. This crossed the strings, with the bass strings in the higher plane.) This permitted a much narrower cabinet at the "nose" end of the piano, and optimized the transition from unwound tenor strings to the iron or copper-wrapped bass strings. Over-stringing was invented by Pape during the 1820s, and first patented for use in grand pianos in the United States by Henry Steinway, Jr. in 1859.

Some piano makers developed schemes to enhance the tone of each note. Julius Blüthner developed Aliquot stringing in 1893 as well as Pascal Taskin (1788),[15] and Collard & Collard (1821). Each used more distinctly ringing, undamped vibrations to modify tone, except the Blüthner Aliquot stringing, which uses an additional fourth string in the upper two treble sections. While the hitchpins of these separately suspended Aliquot strings are raised slightly above the level of the usual tri-choir strings, they are not struck by the hammers but rather are damped by attachments of the usual dampers. Eager to copy these effects, Theodore Steinway invented duplex scaling, which used short lengths of non-speaking wire bridged by the aliquot throughout much of upper the range of the piano, always in locations that caused them to vibrate in conformity with their respective overtones—typically in doubled octaves and twelfths.

The mechanical action structure of the upright piano was invented in London, England in 1826 by Robert Wornum, and upright models became the most popular model, also amplifying the sound.[16]

Variations in shape and design

Some early pianos had shapes and designs that are no longer in use. The square piano (not truly square, but rectangular) was cross strung at an extremely acute angle above the hammers, with the keyboard set along the long side. This design is attributed to Gottfried Silbermann or Christian Ernst Friderici on the continent, and Johannes Zumpe or Harman Vietor in England, and it was improved by changes first introduced by Guillaume-Lebrecht Petzold in France and Alpheus Babcock in the United States. Square pianos were built in great numbers through the 1840s in Europe and the 1890s in the United States, and saw the most visible change of any type of piano: the iron-framed, over-strung squares manufactured by Steinway & Sons were more than two-and-a-half times the size of Zumpe's wood-framed instruments from a century before. Their overwhelming popularity was due to inexpensive construction and price, although their tone and performance were limited by narrow soundboards, simple actions and string spacing that made proper hammer alignment difficult.

The tall, vertically strung upright grand was arranged like a grand set on end, with the soundboard and bridges above the keys, and tuning pins below them. The term was later revived by many manufacturers for advertising purposes. Giraffe, pyramid and lyre pianos were arranged in a somewhat similar fashion in evocatively shaped cases.

The very tall cabinet piano was introduced about 1805 and was built through the 1840s. It had strings arranged vertically on a continuous frame with bridges extended nearly to the floor, behind the keyboard and very large sticker action. The short cottage upright or pianino with vertical stringing, made popular by Robert Wornum around 1815, was built into the 20th century. They are informally called birdcage pianos because of their prominent damper mechanism. The oblique upright, popularized in France by Roller & Blanchet during the late 1820s, was diagonally strung throughout its compass. The tiny spinet upright was manufactured from the mid-1930s until recent times. The low position of the hammers required the use of a "drop action" to preserve a reasonable keyboard height.

Modern upright and grand pianos attained their present forms by the end of the 19th century. Improvements have been made in manufacturing processes, and many individual details of the instrument continue to receive attention.

Types

Modern acoustic pianos have two basic configurations, the grand piano and the upright piano, with various styles of each. There are also specialized and novelty pianos, electric pianos based on electromechanical designs, electronic pianos that synthesize piano-like tones using oscillators, and digital pianos using digital samples of acoustic piano sounds.

Grand

Steinway grand piano in the White House  August Förster upright piano |

In grand pianos, the frame and strings are horizontal, with the strings extending away from the keyboard. The action lies beneath the strings, and uses gravity as its means of return to a state of rest.

There are many sizes of grand piano. A rough generalization distinguishes the concert grand (between 2.2 and 3 meters long, about 7–10 feet) from the parlor grand or boudoir grand (1.7 to 2.2 meters long, about 6–7 feet) and the smaller baby grand (around 1.5 metres (5 feet)).

All else being equal, longer pianos with longer strings have larger, richer sound and lower inharmonicity of the strings. Inharmonicity is the degree to which the frequencies of overtones (known as partials or harmonics) sound sharp relative to whole multiples of the fundamental frequency. This results from the piano's considerable string stiffness; as a struck string decays its harmonics vibrate, not from their termination, but from a point very slightly toward the center (or more flexible part) of the string. The higher the partial, the further sharp it runs. Pianos with shorter and thicker string (i.e., small pianos with short string scales) have more inharmonicity. The greater the inharmonicity, the more the ear perceives it as harshness of tone.

Inharmonicity requires that octaves be stretched, or tuned to a lower octave's corresponding sharp overtone rather than to a theoretically correct octave. If octaves are not stretched, single octaves sound in tune, but double—and notably triple—octaves are unacceptably narrow. Stretching a small piano's octaves to match its inherent inharmonicity level creates an imbalance among all the instrument's intervallic relationships, not just its octaves. In a concert grand, however, the octave "stretch" retains harmonic balance, even when aligning treble notes to a harmonic produced from three octaves below. This lets close and widespread octaves sound pure, and produces virtually beatless perfect fifths. This gives the concert grand a brilliant, singing and sustaining tone quality—one of the principal reasons that full-size grands are used in the concert hall. Smaller grands satisfy the space and cost needs of domestic use.

Upright (vertical)

Upright pianos, also called vertical pianos, are more compact because the frame and strings are vertical. Upright pianos are widely used in music conservatories and university music programs as rehearsal and practice instruments and they are popular models for in-home purchase. The hammers move horizontally, and return to their resting position via springs, which are susceptible to degradation. Upright pianos with unusually tall frames and long strings are sometimes called upright grand pianos. Some authors classify modern pianos according to their height and to modifications of the action that are necessary to accommodate the height.

- Studio pianos are around 42 to 45 inches (106 to 114 cm) tall. This is the shortest cabinet that can accommodate a full-sized action located above the keyboard.

- Console pianos have a compact action (shorter hammers), and are a few inches shorter than studio models.

- The top of a spinet model barely rises above the keyboard. The action is located below, operated by vertical wires that are attached to the backs of the keys.

- Anything taller than a studio piano is called an upright.

Specialized

The toy piano, introduced in the 19th century, is a small piano-like instrument, that generally uses round metal rods to produce sound, rather than strings. The US Library of Congress recognizes the toy piano as a unique instrument with the subject designation, Toy Piano Scores: M175 T69.[17]

In 1863, Henri Fourneaux invented the player piano, which plays itself from a piano roll. A machine perforates a performance recording into rolls of paper, and the player piano replays the performance using pneumatic devices. Modern equivalents of the player piano include the Bösendorfer CEUS, Yamaha Disklavier and QRS Pianomation,[18] using solenoids and MIDI rather than pneumatics and rolls.

A silent piano is an acoustic piano having an option to silence the strings by means of an interposing hammer bar. They are designed for private silent practice.

Edward Ryley invented the transposing piano in 1801. It has a lever under the keyboard as to move the keyboard relative to the strings so a pianist can play in a familiar key while the music sounds in a different key.

The minipiano, an instrument patented by the Brasted brothers of the Eavestaff Ltd. piano company, was patented in 1934.[19] This instrument has a braceless back, and a soundboard positioned below the keys—meaning that long metal rods pulled on the levers to make the hammers strike the strings. The first model, known as the Pianette,' was unique in that the tuning pins extended through the instrument, so it could be tuned at the front.

The prepared piano, present in some contemporary art music, is a piano with objects placed inside it to alter its sound, or has had its mechanism changed in some other way. The scores for music for prepared piano specify the modifications, for example instructing the pianist to insert pieces of rubber, paper, metal screws, or washers in between the strings. These either mute the strings or alter their timbre. A harpsichord-like sound can be produced by placing or dangling small metal buttons in front of the hammer.

In 1954 a German company exhibited a wire-less piano at the Spring Fair in Frankfurt, Germany that sold for $238. The wires were replaced by metal bars of different alloys that replicated the standard wires when played.[20] A similar concept is used in the electric-acoustic Rhodes piano.

Electric, electronic, and digital

Electric pianos have metal tines in place of strings and use electromagnetic pickups similar to those on an electric guitar. The resulting electrical, analogue signal can then be amplified with a keyboard amplifier or electronically manipulated with effects units if required. Electric pianos are rarely used in classical music, where the main usage of them is as inexpensive rehearsal instruments in music schools. However, electric pianos, particularly the Fender Rhodes, became important instruments in funk, jazz fusion and some rock music genres.

Electronic pianos are non-acoustic; they do not have strings but are a simple type of synthesizer that simulates piano sounds using oscillators that synthesize the sound of an acoustic piano.[21]

Digital pianos are also non-acoustic and do not have strings but use digital sampling technology to reproduce the sound of each piano note. Digital pianos can include pedals, weighted keys, multiple voices, and MIDI interfaces. Early digital pianos tended to lack a full set of pedals but the synthesis software of later models such as the Yamaha Clavinova series synthesised the sympathetic vibration of the other strings and full pedal sets can now be replicated. The processing power of digital pianos has enabled highly realistic pianos using multi-gigabyte piano sample sets with as many as ninety recordings, each lasting many seconds, for each key under different conditions. Additional samples emulate sympathetic resonance, key release, the drop of the dampers, and simulations of techniques such as re-pedalling.

Digital, MIDI compliant, pianos can output a stream of MIDI data, or record and play via a CDROM or USB flash drive using MIDI format files, similar in concept to a pianola. The MIDI file records the physics of a note rather than its resulting sound and recreates the sounds from its physical properties. Computer based software, such as Modartt's 2006 Pianoteq, can be used to manipulate the MIDI stream in real time or subsequently to edit it. This type of software may use no samples but synthesise a sound based on aspects of the physics that went into the creation of a played note.

Construction and components

Pianos can have upwards of 12,000 individual parts,[22] supporting six functional features: keyboard, hammers, dampers, bridge, soundboard, and strings.[23]

Many parts of a piano are made of materials selected for strength and longevity. This is especially true of the outer rim. It is most commonly made of hardwood, typically hard maple or beech, and its massiveness serves as an essentially immobile object from which the flexible soundboard can best vibrate. According to Harold A. Conklin,[24] the purpose of a sturdy rim is so that, "... the vibrational energy will stay as much as possible in the soundboard instead of dissipating uselessly in the case parts, which are inefficient radiators of sound."

Hardwood rims are commonly made by laminating thin, hence flexible, strips of hardwood, bending them to the desired shape immediately after the application of glue.[25] The bent plywood system was developed by C.F. Theodore Steinway in 1880 to reduce manufacturing time and costs. Previously, the rim was constructed from several pieces of solid wood, joined and veneered, and this method continued to be used in Europe well into the 20th century.[26] A modern exception, Bösendorfer, the Austrian manufacturer of high-quality pianos, constructs their inner rims from solid spruce,[27] the same wood that the soundboard is made from, which is notched to allow it to bend; rather than isolating the rim from vibration, their "resonance case principle" allows the framework to more freely resonate with the soundboard, creating additional coloration and complexity of the overall sound.[28]

The thick wooden posts on the underside (grands) or back (uprights) of the piano stabilize the rim structure, and are made of softwood for stability. The requirement of structural strength, fulfilled by stout hardwood and thick metal, makes a piano heavy. Even a small upright can weigh 136 kg (300 lb), and the Steinway concert grand (Model D) weighs 480 kg (990 lb). The largest piano available on the general market, the Fazioli F308, weighs 570 kg (1257 lb).[29][30]

The pinblock, which holds the tuning pins in place, is another area where toughness is important. It is made of hardwood (typically hard maple or beech), and is laminated for strength, stability and longevity. Piano strings (also called piano wire), which must endure years of extreme tension and hard blows, are made of high carbon steel. They are manufactured to vary as little as possible in diameter, since all deviations from uniformity introduce tonal distortion. The bass strings of a piano are made of a steel core wrapped with copper wire, to increase their mass whilst retaining flexibility. If all strings throughout the piano's compass were individual (monochord), the massive bass strings would overpower the upper ranges. Makers compensate for this with the use of double (bichord) strings in the tenor and triple (trichord) strings throughout the treble.

The plate (harp), or metal frame, of a piano is usually made of cast iron. A massive plate is advantageous. Since the strings vibrate from the plate at both ends, an insufficiently massive plate would absorb too much of the vibrational energy that should go through the bridge to the soundboard. While some manufacturers use cast steel in their plates, most prefer cast iron. Cast iron is easy to cast and machine, has flexibility sufficient for piano use, is much more resistant to deformation than steel, and is especially tolerant of compression. Plate casting is an art, since dimensions are crucial and the iron shrinks about one percent during cooling.

Including an extremely large piece of metal in a piano is potentially an aesthetic handicap. Piano makers overcome this by polishing, painting, and decorating the plate. Plates often include the manufacturer's ornamental medallion. In an effort to make pianos lighter, Alcoa worked with Winter and Company piano manufacturers to make pianos using an aluminum plate during the 1940s. Aluminum piano plates were not widely accepted, and were discontinued.

The numerous parts of a piano action are generally made from hardwood, such as maple, beech, and hornbeam, however, since World War II, makers have also incorporated plastics. Early plastics used in some pianos in the late 1940s and 1950s, proved disastrous when they lost strength after a few decades of use. Beginning in 1961, the New York branch of the Steinway firm incorporated Teflon, a synthetic material developed by DuPont, for some parts of its Permafree grand action in place of cloth bushings, but abandoned the experiment in 1982 due to excessive friction and a "clicking" that developed over time; Teflon is "humidity stable" whereas the wood adjacent to the Teflon swells and shrinks with humidity changes, causing problems. More recently, the Kawai firm built pianos with action parts made of more modern materials such as carbon fiber reinforced plastic, and the piano parts manufacturer Wessell, Nickel and Gross has launched a new line of carefully engineered composite parts. Thus far these parts have performed reasonably, but it will take decades to know if they equal the longevity of wood.

In all but the poorest pianos the soundboard is made of solid spruce (that is, spruce boards glued together along the side grain). Spruce's high ratio of strength to weight minimizes acoustic impedance while offering strength sufficient to withstand the downward force of the strings. The best piano makers use quarter-sawn, defect-free spruce of close annular grain, carefully seasoning it over a long period before fabricating the soundboards. This is the identical material that is used in quality acoustic guitar soundboards. Cheap pianos often have plywood soundboards.[31]

Keyboard

In the early years of piano construction, keys were commonly made from sugar pine. Today they are usually made of spruce or basswood. Spruce is typically used in high-quality pianos. Black keys were traditionally made of ebony, and the white keys were covered with strips of ivory. However, since ivory-yielding species are now endangered and protected by treaty, makers use plastics almost exclusively. Also, ivory tends to chip more easily than plastic. Legal ivory can still be obtained in limited quantities. The Yamaha firm invented a plastic called Ivorite that they claim mimics the look and feel of ivory. It has since been imitated by other makers.

Almost every modern piano has 52 white keys and 36 black keys for a total of 88 keys (seven octaves plus a minor third, from A0 to C8). Many older pianos only have 85 keys (seven octaves from A0 to A7). Some piano manufacturers extend the range further in one or both directions.

Some Bösendorfer pianos, for example, extend the normal range down to F0, and one of their models which has 97 keys even goes as far as a bottom C0, making a full eight octave range. These extra keys are sometimes hidden under a small hinged lid that can cover the keys to prevent visual disorientation for pianists unfamiliar with the extra keys, or the colors of the extra white keys are reversed (black instead of white).

The extra keys are added primarily for increased resonance from the associated strings; that is, they vibrate sympathetically with other strings whenever the damper pedal is depressed and thus give a fuller tone. Only a very small number of works composed for piano actually use these notes. More recently, the Stuart and Sons company has also manufactured extended-range pianos, with the first 102 key piano. On their instruments, the frequency range extends from C0 to F8, which is the widest practical range for the acoustic piano. The extra keys are the same as the other keys in appearance.

Small studio upright acoustical pianos with only 65 keys have been manufactured for use by roving pianists. Known as gig pianos and still containing a cast iron harp (frame), these are comparatively lightweight and can be easily transported to and from engagements by only two people. As their harp is longer than that of a spinet or console piano, they have a stronger bass sound that to some pianists is well worth the trade-off in range that a reduced key-set offers.

The toy piano manufacturer Schoenhut started manufacturing both grands and uprights with only 44 or 49 keys, and shorter distance between the keyboard and the pedals. These pianos are true pianos with action and strings. The pianos were introduced to their product line in response to numerous requests in favor of it.

There is a rare variants of piano that has double keyboards called the Emánuel Moór Pianoforte. It was invented by Hungarian composer and pianist, Emánuel Moór (19 February 1863 – 20 October 1931). It consisted of two keyboards lying one above each other. The lower keyboard has the usual 88 keys and the upper keyboard has 76 keys. When pressing the upper keyboard the internal mechanism pulls down the corresponding key on the lower keyboard, but an octave higher. This allow pianist to easily reach two octave with one hand which was impossible to do so on a conventional piano. Due to its double keyboard musical work that were originally created for double-manual Harpsichord such as Goldberg Variations by Bach become much easier to play, since playing on a conventional single keyboard piano involve complex and hand-tangling cross-hand movements. The design also featured a special forth pedal which pair the lower keyboard with upper keyboard, so when playing on the lower keyboard the note one octave higher would also be played as if the pianist had also pressed the upper keyboard. Only about 60 Emánuel Moór Pianoforte were made, mostly manufactured by Bösendorfer. Other piano manufactures such as Bechstein, Chickering, and Steinway & Sons had also manufactured a few.[32]

Pianos have been built with alternative keyboard systems, e.g., the Jankó keyboard.

Pedals

Pianos have had pedals, or some close equivalent, since the earliest days. (In the 18th century, some pianos used levers pressed upward by the player's knee instead of pedals.) Most grand pianos in the US have three pedals: the soft pedal (una corda), sostenuto, and sustain pedal (from left to right, respectively), while in Europe, the standard is two pedals: the soft pedal and the sustain pedal. Most modern upright pianos also have three pedals: soft pedal, practice pedal and sustain pedal, though older or cheaper models may lack the practice pedal. In Europe the standard for upright pianos is two pedals: the soft and the sustain pedals.

The sustain pedal (or, damper pedal) is often simply called "the pedal", since it is the most frequently used. It is placed as the rightmost pedal in the group. It lifts the dampers from all keys, sustaining all played notes. In addition, it alters the overall tone by allowing all strings, including those not directly played, to reverberate.

The soft pedal or una corda pedal is placed leftmost in the row of pedals. In grand pianos it shifts the entire action/keyboard assembly to the right (a very few instruments have shifted left) so that the hammers hit two of the three strings for each note. In the earliest pianos whose unisons were bichords rather than trichords, the action shifted so that hammers hit a single string, hence the name una corda, or 'one string'. The effect is to soften the note as well as change the tone. In uprights this action is not possible; instead the pedal moves the hammers closer to the strings, allowing the hammers to strike with less kinetic energy. This produces a slightly softer sound, but no change in timbre.

On grand pianos, the middle pedal is a sostenuto pedal. This pedal keeps raised any damper already raised at the moment the pedal is depressed. This makes it possible to sustain selected notes (by depressing the sostenuto pedal before those notes are released) while the player's hands are free to play additional notes (which aren't sustained). This can be useful for musical passages with pedal points and other otherwise tricky or impossible situations.

On many upright pianos, the middle pedal is called the "practice" or celeste pedal. This drops a piece of felt between the hammers and strings, greatly muting the sounds. This pedal can be shifted while depressed, into a "locking" position.

There are also non-standard variants. On some pianos (grands and verticals), the middle pedal can be a bass sustain pedal: that is, when it is depressed, the dampers lift off the strings only in the bass section. Players use this pedal to sustain a single bass note or chord over many measures, while playing the melody in the treble section. On the Stuart and Sons piano as well as the largest Fazioli piano, there is a fourth pedal to the left of the principal three. This fourth pedal works in the same way as the soft pedal of an upright piano, moving the hammers closer to the strings.[33]

The rare transposing piano (an example of which was owned by Irving Berlin) has a middle pedal that functions as a clutch that disengages the keyboard from the mechanism, so the player can move the keyboard to the left or right with a lever. This shifts the entire piano action so the pianist can play music written in one key so that it sounds in a different key.

Some piano companies have included extra pedals other than the standard two or three. Crown and Schubert Piano Co. produced a four-pedal piano. Fazioli currently offers a fourth pedal that provides a second soft pedal, that works by bringing the keys closer to the strings.

Wing and Son of New York offered a five-pedal piano from approximately 1893 through the 1920s. There is no mention of the company past the 1930s. Labeled left to right, the pedals are Mandolin, Orchestra, Expression, Soft, and Forte (Sustain). The Orchestral pedal produced a sound similar to a tremolo feel by bouncing a set of small beads dangling against the strings, enabling the piano to mimic a mandolin, guitar, banjo, zither and harp, thus the name Orchestral. The Mandolin pedal used a similar approach, lowering a set of felt strips with metal rings in between the hammers and the strings ( aka rinky-tink effect). This extended the life of the hammers when the Orch pedal was used, a good idea for practicing, and created an echo-like sound that mimicked playing in an orchestral hall.[34][35]

The pedalier piano, or pedal piano, is a rare type of piano that includes a pedalboard so players can user their feet to play bass register notes, as on an organ. There are two types of pedal piano. On one, the pedal board is an integral part of the instrument, using the same strings and mechanism as the manual keyboard. The other, rarer type, consists of two independent pianos (each with separate mechanics and strings) placed one above the other—one for the hands and one for the feet. This was developed primarily as a practice instrument for organists, though there is a small repertoire written specifically for the instrument.

Mechanics

When the key is struck, a chain reaction occurs to produce the sound. First, the key raises the wippen, which forces the jack against the hammer roller (or knuckle). The hammer roller then lifts the lever carrying the hammer. The key also raises the damper; and immediately after the hammer strikes the wire it falls back, allowing the wire to resonate. When the key is released the damper falls back onto the strings, stopping the wire from vibrating.[36] The vibrating piano strings themselves are not very loud, but their vibrations are transmitted to a large soundboard that moves air and thus converts the energy to sound. The irregular shape and off-center placement of the bridge ensure that the soundboard vibrates strongly at all frequencies.[37] (See Piano action for a diagram and detailed description of piano parts.)

There are three factors that influence the pitch of a vibrating wire.

- Length: All other factors the same, the shorter the wire, the higher the pitch.

- Mass per unit length: All other factors the same, the thinner the wire, the higher the pitch.

- Tension: All other factors the same, the tighter the wire, the higher the pitch.

A vibrating wire subdivides itself into many parts vibrating at the same time. Each part produces a pitch of its own, called a partial. A vibrating string has one fundamental and a series of partials. The most pure combination of two pitches is when one is double the frequency of the other.[38]

For a repeating wave, the velocity v equals the wavelength λ times the frequency f,

- v = λf

On the piano string, waves reflect from both ends. The superposition of reflecting waves results in a standing wave pattern, but only for wavelengths λ = 2L, L, L/2, ... = 2L/n, where L is the length of the string. Therefore, the only frequencies produced on a single string are f = nv/(2L). Timbre is largely determined by the content of these harmonics. Different instruments have different harmonic content for the same pitch. A real string vibrates at harmonics that are not perfect multiples of the fundamental. This results in a little inharmonicity, which gives richness to the tone but causes significant tuning challenges throughout the compass of the instrument.[37]

Striking the piano key with greater velocity increases the amplitude of the waves and therefore the volume. From pianissimo (pp) to fortissimo (ff) the hammer velocity changes by almost a factor of a hundred. The hammer contact time with the string shortens from 4 ms at pp to less than 2 ms at ff.[37] If two wires adjusted to the same pitch are struck at the same time, the sound produced by one reinforces the other, and a louder combined sound of shorter duration is produced. If one wire vibrates out of synchronization with the other, they subtract from each other and produce a softer tone of longer duration.[39]

Maintenance

Pianos are heavy yet delicate instruments. Over the years, professional piano movers have developed special techniques for transporting both grands and uprights, which prevent damage to the case and to the piano's mechanics. Pianos need regular tuning to keep them on pitch. The hammers of pianos are voiced to compensate for gradual hardening, and other parts also need periodic regulation. Aged and worn pianos can be rebuilt or reconditioned. Often, by replacing a great number of their parts, they can perform as well as new pianos.

Tuning

Piano tuning involves adjusting the tensions of the piano's strings, thereby aligning the intervals among their tones so that the instrument is in tune. The meaning of the term in tune in the context of piano tuning is not simply a particular fixed set of pitches. Fine piano tuning carefully assesses the interaction among all notes of the chromatic scale, different for every piano, and thus requires slightly different pitches from any theoretical standard. Pianos are usually tuned to a modified version of the system called equal temperament (see Piano key frequencies for the theoretical piano tuning). In all systems of tuning, each pitch is derived from its relationship to a chosen fixed pitch, usually the internationally recognized standard concert pitch of A440.

The relationship between two pitches, called an interval, is the ratio of their absolute frequencies. Two different intervals are perceived as the same when the pairs of pitches involved share the same frequency ratio. The easiest intervals to identify, and the easiest intervals to tune, are those that are just, meaning they have a simple whole-number ratio. The term temperament refers to a tuning system that tempers the just intervals (usually the perfect fifth, which has the ratio 3:2) to satisfy another mathematical property; in equal temperament, a fifth is tempered by narrowing it slightly, achieved by flattening its upper pitch slightly, or raising its lower pitch slightly. A temperament system is also known as a set of bearings.

Tempering an interval causes it to beat, which is a fluctuation in perceived sound intensity due to interference between close (but unequal) pitches. The rate of beating is equal to the frequency differences of any harmonics that are present for both pitches and that coincide or nearly coincide.

Playing and technique

As with any other musical instrument, the piano may be played from written music, by ear, or through improvisation. Piano technique evolved during the transition from harpsichord and clavichord to fortepiano playing, and continued through the development of the modern piano. Changes in musical styles and audience preferences, as well as the emergence of virtuoso performers contributed to this evolution, and to the growth of distinct approaches or schools of piano playing. Although technique is often viewed as only the physical execution of a musical idea, many pedagogues and performers stress the interrelatedness of the physical and mental or emotional aspects of piano playing.[40][41][42][43][44]

Well-known approaches to piano technique include those by Dorothy Taubman, Edna Golandsky, Fred Karpoff, and Otto Ortmann.

Performance styles

Many classical music composers, including Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, composed for the fortepiano, a rather different instrument than the modern piano. Even composers of the Romantic movement, like Liszt, Chopin, Robert Schumann, Felix Mendelssohn, and Johannes Brahms, wrote for pianos substantially different from modern pianos. Contemporary musicians may adjust their interpretation of historical compositions to account for sound quality differences between old and new instruments.

Starting in Beethoven's later career, the fortepiano evolved into the modern piano as we know it today. Modern pianos were in wide use by the late 19th century. They featured an octave range larger than the earlier fortepiano instrument, adding around 30 more keys to the instrument. Factory mass production of upright pianos made them more affordable for a larger number of people. They appeared in music halls and pubs during the 19th century, providing entertainment through a piano soloist, or in combination with a small band. Pianists began accompanying singers or dancers performing on stage, or patrons dancing on a dance floor.

During the 19th century, American musicians playing for working-class audiences in small pubs and bars, particularly African-American composers, developed new musical genres based on the modern piano. Ragtime music, popularized by composers such as Scott Joplin, reached a broader audience by 1900. The popularity of ragtime music was quickly succeeded by Jazz piano. New techniques and rhythms were invented for the piano, including ostinato for boogie-woogie, and Shearing voicing. George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue broke new musical ground by combining American jazz piano with symphonic sounds. Comping, a technique for accompanying jazz vocalists on piano, was exemplified by Duke Ellington's technique. Honky-tonk music, featuring yet another style of piano rhythm, became popular during the same era. Bebop techniques grew out of jazz, with leading composers such as Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell. In the late 20th century, Bill Evans composed pieces combining classical techniques with his jazz experimentation. Herbie Hancock was one of the first jazz pianists to find mainstream popularity working with newer urban music techniques.

Pianos have also been used prominently in rock and roll by entertainers such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Keith Emerson (Emerson, Lake & Palmer), Elton John, Ben Folds, Billy Joel, Nicky Hopkins, and Tori Amos, to name a few.

Modernist styles of music have also appealed to composers writing for the modern grand piano, including John Cage and Philip Glass.

Role

The piano is a crucial instrument in Western classical music, jazz, blues, rock, folk music, film and television scoring, and many other Western musical genres. A large number of composers are proficient pianists because the piano keyboard offers an effective means of experimenting with complex melodic and harmonic interplay. The piano is an essential tool in music education in universities and colleges, and most classrooms and practice rooms have a piano. Pianos are used to help teach music theory, music history and music appreciation classes. Many conductors are trained in piano, because it allows them to play parts of the symphonies they are conducting (using a piano reduction or doing a reduction from the full score), so that they can develop their interpretation.

See also

- General

- Jazz piano

- Piano extended technique

- Piano transcription

- Piano trio

- PianoForte Foundation

- Street piano

- String piano

- Technical

- Related instruments

- Digital piano

- Electric piano

- Electronic keyboard

- Electronic piano

- Harmonichord

- Keyboard instruments

- Keytar

- Melodica

- Organ

- Orphica

- Piano accordion

- Pipe organ

- Player piano

- Other

References

- ↑ "Definition of "pianoforte" in the Oxford Dictionary.". Oxford University Press.

- ↑ John Kiehl. "Hammer Time". Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- ↑ Pollens (1995, 238)

- ↑ Scholes, Percy A.; John Owen Ward (1970). The Oxford Companion to Music (10th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. lvi.

- ↑ David R. Peterson (1994), "Acoustics of the hammered dulcimer, its history, and recent developments", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 95 (5), p. 3002.

- ↑ Pollens (1995, Ch.1)

- ↑ Erlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford University Press, USA; Revised edition. ISBN 0-19-816171-9.

- 1 2 3 Powers, Wendy (2003). "The Piano: The Pianofortes of Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ↑ Isacoff (2012, 23)

- ↑ Palmieri, Bob & Meg (2003). The Piano: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-93796-2.. "Instrument: piano et forte genandt" [was] an expression Bach also used when acting as Silbermann's agent in 1749."

- ↑ "The Viennese Piano". Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Isacoff (2012, 74)

- 1 2 Dolge (1911, 124)

- ↑ Dolge (1911, 125-126)

- ↑ "Piano à queue" (in French). Médiathèque de la Cité de la musique. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Palmieri, ed., Robert (2003). Encyclopedia of keyboard instruments, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-415-93796-2.

- ↑ Good, Dave (4 September 2012). "M175 T69: Not Child's Play". San Diego Reader. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "PNOmation II". QRS Music Technologies. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ "History of the Eavestaff Pianette Minipiano". Piano-tuners.org. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ↑ "Wireless Piano Exhibited in Germany." Popular Mechanics, April 1954, p. 115, bottom of page.

- ↑ Davies, Hugh (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Second edition). London: Macmillan.

- ↑ "161 Facts About Steinway & Sons and the Pianos They Build". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ↑ Nave, Carl R. "The Piano". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Piano Case". Five Lectures on the Acoustics of the Piano. Royal Swedish Academy of Music. 1990. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ Navi, Parvis; Dick Sandberg (2012). Thermo-Hydro-Mechanical Wood Processing. CRC Press. p. 46. ISBN 1-4398-6042-4.

- ↑ p. 65

- ↑ Fine, Larry (2007). 2007–2008 Annual Supplement to The Piano Book. Brookside Press. p. 31. ISBN 1-929145-21-7.

- ↑ The "resonance case principle" is described by Bösendorfer in terms of manufacturing technique and description of effect.

- ↑ "Fazioli, Paolo", Grove Music Online, 2009. Accessed 12 April 2009.

- ↑ "Model F308", Official Fazioli Website. Accessed 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Fletcher, Neville Horner; Thomas D. Rossing (1998). The Physics of Musical Instruments. Springer. p. 374.

- ↑ Baron, James (July 15, 2007). "Let's Play Two: Singular Piano". New York Times. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- ↑ "Fourth pedal". Fazioli. Archived from the original on 2008-04-16. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ↑ "Piano with instrumental attachments". Musica Viva. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ "Wing & Son". Antique Piano Shop. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Macaulay, David. The New How Things Work. From Levers to Lasers, Windmills to Web Sites, A Visual guide to the World of Machines. Houghton Mifflin Company, United States. 1998. ISBN 0-395-93847-3. pp. 26–27.

- 1 2 3 Physics of the Piano by the Piano Tuners Guild

- ↑ Reblitz, Arthur A. Piano Servicing, Tuning, and Rebuilding. For the Professional, the Student, and the Hobbyist. Vestal Press, Lanham Maryland. 1993. ISBN 1-879511-03-7 Pp. 203–215.

- ↑ Reblitz, Arthur A. Piano Servicing, Tuning, and Rebuilding. For the Professional, the student, and the Hobbyist. Vestal Press, Lanham Maryland. 1993. ISBN 1-879511-03-7 Pp. 203–215.

- ↑ Edwin M. Ripin; et al. "Pianoforte". Grove Music Online (Oxford University Press). Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Matthay, Tobias (1947). The Visible and Invisible in Pianoforte Technique : Being a Digest of the Author's Technical Teachings Up to Date. London: Oxford University Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Harrison, Sidney (1953). Piano Technique. London: I. Pitman. p. 57.

- ↑ Fielden, Thomas (1934). The Science of Pianoforte Technique. London: Macmillan. p. 162.

- ↑ Boulanger, Nadia. "Sayings of Great Teachers". The Piano Quarterly. Winter 1958–1959: 26.

- Dolge, Alfred (1911). Pianos and Their Makers: A Comprehensive History of the Development of the Piano from the Monochord to the Concert Grand Player Piano. Covina Publishing Company.

- Isacoff, Stuart (2012). A Natural History of the Piano: The Instrument, the Music, the Musicians - From Mozart to Modern Jazz and Everything in Between. Knopf Doubleday Publishing.

General

Most of the information in this article can be found in the following published works:

- Fine, Larry; Gilbert, Douglas R (2001). The Piano Book: Buying and Owning a New or Used Piano (4th ed.). Jamaica Plain, MA: Brookside Press. ISBN 1-929145-01-2. Gives the basics of how pianos work, and a thorough evaluative survey of current pianos and their manufacturers. It also includes advice on buying and owning pianos.

- Good, Edwin M. (2001). Giraffes, black dragons, and other pianos: a technological history from Cristofori to the modern concert grand (2nd ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4549-8. is a standard reference on the history of the piano.

- Pollens, Stewart (1995). The Early Pianoforte. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11155-3. is an authoritative work covering the ancestry of the piano, its invention by Cristofori, and the early stages of its subsequent evolution.

- Sadie, Stanley; John Tyrrell, ed. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-19-517067-9. contains a wealth of information. Main article: Edwin M. Ripin, Stewart Pollens, Philip R. Belt, Maribel Meisel, Alfons Huber, Michael Cole, Gert Hecher, Beryl Kenyon de Pascual, Cynthia Adams Hoover, Cyril Ehrlich, Edwin M. Good, Robert Winter, and J. Bradford Robinson. "Pianoforte".

Further reading

- Banowetz, Joseph; Elder, Dean (1985). The pianist's guide to pedaling. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34494-8.

- Carhart, Thad (2002) [2001]. The Piano Shop on the Left Bank. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-75862-3.

- Ehrlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816171-4.

- Giordano, Sr., Nicholas J. (2010). Physics of the Piano. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954602-2.

- Lelie, Christo (1995). Van Piano tot Forte (The History of the Early Piano) (in Dutch). Kampen: Kok-Lyra.

- Loesser, Arthur (1991) [1954]. Men, Women, and Pianos: A Social History. New York: Dover Publications.

- Parakilas, James (1999). Piano Roles: Three Hundred Years of Life with the Piano. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08055-7.

- Reblitz, Arthur A. (1993). Piano Servicing, Tuning and Rebuilding: For the Professional, the Student, and the Hobbyist. Vestal, NY: Vestal Press. ISBN 1-879511-03-7.

- Schejtman, Rod (2008). Music Fundamentals. The Piano Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-987-25216-2-2.

- White, William H. (1909). Theory and Practice of Pianoforte-Building. New York: E. Lyman Bill.

External links

- History of the Piano Forte, Association of Blind Piano Tuners, UK

- Section Table of Music Pitches of the Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary

- The Frederick Historical Piano Collection

- The Pianofortes of Bartolomeo Cristofori, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Five lectures on the Acoustics of the piano

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|