Photoelectric effect

| Light–matter interaction |

|---|

|

| Low-energy phenomena: |

| Photoelectric effect |

| Mid-energy phenomena: |

| Thomson scattering |

| Compton scattering |

| High-energy phenomena: |

| Pair production |

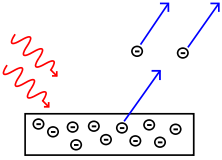

The photoelectric effect is the observation that many metals emit electrons when light shines upon them. Electrons emitted in this manner can be called photoelectrons. The phenomenon is commonly studied in electronic physics, as well as in fields of chemistry, such as quantum chemistry or electrochemistry.

According to classical electromagnetic theory, this effect can be attributed to the transfer of energy from the light to an electron in the metal. From this perspective, an alteration in either the intensity or wavelength of light would induce changes in the rate of emission of electrons from the metal. Furthermore, according to this theory, a sufficiently dim light would be expected to show a time lag between the initial shining of its light and the subsequent emission of an electron. However, the experimental results did not correlate with either of the two predictions made by classical theory.

Instead, electrons are only dislodged by the impingement of photons when those photons reach or exceed a threshold frequency. Below that threshold, no electrons are emitted from the metal regardless of the light intensity or the length of time of exposure to the light. To make sense of the fact that light can eject electrons even if its intensity is low, Albert Einstein proposed that a beam of light is not a wave propagating through space, but rather a collection of discrete wave packets (photons), each with energy hf. This shed light on Max Planck's previous discovery of the Planck relation (E = hf) linking energy (E) and frequency (f) as arising from quantization of energy. The factor h is known as the Planck constant.[1][2]

In 1887, Heinrich Hertz[2][3] discovered that electrodes illuminated with ultraviolet light create electric sparks more easily. In 1905 Albert Einstein published a paper that explained experimental data from the photoelectric effect as the result of light energy being carried in discrete quantized packets. This discovery led to the quantum revolution. In 1914, Robert Millikan's experiment confirmed Einstein's law on photoelectric effect. Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921 for "his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[4] and Millikan was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923 for "his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect".[5]

The photoelectric effect requires photons with energies from a few electronvolts to over 1 MeV in elements with a high atomic number. Study of the photoelectric effect led to important steps in understanding the quantum nature of light and electrons and influenced the formation of the concept of wave–particle duality.[1] Other phenomena where light affects the movement of electric charges include the photoconductive effect (also known as photoconductivity or photoresistivity), the photovoltaic effect, and the photoelectrochemical effect.

Emission mechanism

The photons of a light beam have a characteristic energy proportional to the frequency of the light. In the photoemission process, if an electron within some material absorbs the energy of one photon and acquires more energy than the work function (the electron binding energy) of the material, it is ejected. If the photon energy is too low, the electron is unable to escape the material. Since an increase in the intensity of low-frequency light will only increase the number of low-energy photons sent over a given interval of time, this change in intensity will not create any single photon with enough energy to dislodge an electron. Thus, the energy of the emitted electrons does not depend on the intensity of the incoming light, but only on the energy (equivalently frequency) of the individual photons. It is an interaction between the incident photon and the outermost electrons.

Electrons can absorb energy from photons when irradiated, but they usually follow an "all or nothing" principle. All of the energy from one photon must be absorbed and used to liberate one electron from atomic binding, or else the energy is re-emitted. If the photon energy is absorbed, some of the energy liberates the electron from the atom, and the rest contributes to the electron's kinetic energy as a free particle.[6][7][8]

Experimental observations of photoelectric emission

The theory of the photoelectric effect must explain the experimental observations of the emission of electrons from an illuminated metal surface.

For a given metal, there exists a certain minimum frequency of incident radiation below which no photoelectrons are emitted. This frequency is called the threshold frequency. Increasing the frequency of the incident beam, keeping the number of incident photons fixed (this would result in a proportionate increase in energy) increases the maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons emitted. Thus the stopping voltage increases. The number of electrons also changes because the probability that each photon results in an emitted electron is a function of photon energy. If the intensity of the incident radiation of a given frequency is increased, there is no effect on the kinetic energy of each photoelectron.

Above the threshold frequency, the maximum kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectron depends on the frequency of the incident light, but is independent of the intensity of the incident light so long as the latter is not too high.[9]

For a given metal and frequency of incident radiation, the rate at which photoelectrons are ejected is directly proportional to the intensity of the incident light. An increase in the intensity of the incident beam (keeping the frequency fixed) increases the magnitude of the photoelectric current, although the stopping voltage remains the same.

The time lag between the incidence of radiation and the emission of a photoelectron is very small, less than 10−9 second.

The direction of distribution of emitted electrons peaks in the direction of polarization (the direction of the electric field) of the incident light, if it is linearly polarized.[10]

Mathematical description

The maximum kinetic energy  of an ejected electron is given by

of an ejected electron is given by

where  is the Planck constant and

is the Planck constant and  is the frequency of the incident photon. The term

is the frequency of the incident photon. The term  is the work function (sometimes denoted

is the work function (sometimes denoted  , or

, or  [11]), which gives the minimum energy required to remove a delocalised electron from the surface of the metal. The work function satisfies

[11]), which gives the minimum energy required to remove a delocalised electron from the surface of the metal. The work function satisfies

where  is the threshold frequency for the metal. The maximum kinetic energy of an ejected electron is then

is the threshold frequency for the metal. The maximum kinetic energy of an ejected electron is then

Kinetic energy is positive, so we must have  for the photoelectric effect to occur.[12]

for the photoelectric effect to occur.[12]

Stopping potential

The relation between current and applied voltage illustrates the nature of the photoelectric effect. For discussion, a light source illuminates a plate P, and another plate electrode Q collects any emitted electrons. We vary the potential between P and Q and measure the current flowing in the external circuit between the two plates.

If the frequency and the intensity of the incident radiation are fixed, the photoelectric current increases gradually with an increase in the positive potential on the collector electrode until all the photoelectrons emitted are collected. The photoelectric current attains a saturation value and does not increase further for any increase in the positive potential. The saturation current increases with the increase of the light intensity. It also increases with greater frequencies due to a greater probability of electron emission when collisions happen with higher energy photons.

If we apply a negative potential to the collector plate Q with respect to the plate P and gradually increase it, the photoelectric current decreases, becoming zero at a certain negative potential. The negative potential on the collector at which the photoelectric current becomes zero is called the stopping potential or cut off potential[13]

i. For a given frequency of incident radiation, the stopping potential is independent of its intensity.

ii. For a given frequency of incident radiation, the stopping potential is determined by the maximum kinetic energy  of the photoelectrons that are emitted. If qe is the charge on the electron and

of the photoelectrons that are emitted. If qe is the charge on the electron and  is the stopping potential, then the work done by the retarding potential in stopping the electron is

is the stopping potential, then the work done by the retarding potential in stopping the electron is  , so we have

, so we have

Recalling

we see that the stopping voltage varies linearly with frequency of light, but depends on the type of material. For any particular material, there is a threshold frequency that must be exceeded, independent of light intensity, to observe any electron emission.

Three-step model

In the X-ray regime, the photoelectric effect in crystalline material is often decomposed into three steps:[14]:50–51

- Inner photoelectric effect (see photodiode below). The hole left behind can give rise to Auger effect, which is visible even when the electron does not leave the material. In molecular solids phonons are excited in this step and may be visible as lines in the final electron energy. The inner photoeffect has to be dipole allowed. The transition rules for atoms translate via the tight-binding model onto the crystal. They are similar in geometry to plasma oscillations in that they have to be transversal.

- Ballistic transport of half of the electrons to the surface. Some electrons are scattered.

- Electrons escape from the material at the surface.

In the three-step model, an electron can take multiple paths through these three steps. All paths can interfere in the sense of the path integral formulation. For surface states and molecules the three-step model does still make some sense as even most atoms have multiple electrons which can scatter the one electron leaving.

History

When a surface is exposed to electromagnetic radiation above a certain threshold frequency (typically visible light for alkali metals, near ultraviolet for other metals, and extreme ultraviolet for non-metals), the radiation is absorbed and electrons are emitted. Light, and especially ultra-violet light, discharges negatively electrified bodies with the production of rays of the same nature as cathode rays.[15] Under certain circumstances it can directly ionize gases.[15] The first of these phenomena was discovered by Hertz and Hallwachs in 1887.[15] The second was announced first by Philipp Lenard in 1900.[15]

The ultra-violet light to produce these effects may be obtained from an arc lamp, or by burning magnesium, or by sparking with an induction coil between zinc or cadmium terminals, the light from which is very rich in ultra-violet rays. Sunlight is not rich in ultra-violet rays, as these have been absorbed by the atmosphere, and it does not produce nearly so large an effect as the arc-light. Many substances besides metals discharge negative electricity under the action of ultraviolet light: lists of these substances will be found in papers by G. C. Schmidt[16] and O. Knoblauch.[17]

19th century

In 1839, Alexandre Edmond Becquerel discovered the photovoltaic effect while studying the effect of light on electrolytic cells.[18] Though not equivalent to the photoelectric effect, his work on photovoltaics was instrumental in showing a strong relationship between light and electronic properties of materials. In 1873, Willoughby Smith discovered photoconductivity in selenium while testing the metal for its high resistance properties in conjunction with his work involving submarine telegraph cables.[19]

Johann Elster (1854–1920) and Hans Geitel (1855–1923), students in Heidelberg, developed the first practical photoelectric cells that could be used to measure the intensity of light.[20][21]:458 Elster and Geitel had investigated with great success the effects produced by light on electrified bodies.[22]

In 1887, Heinrich Hertz observed the photoelectric effect and the production and reception of electromagnetic waves.[15] He published these observations in the journal Annalen der Physik. His receiver consisted of a coil with a spark gap, where a spark would be seen upon detection of electromagnetic waves. He placed the apparatus in a darkened box to see the spark better. However, he noticed that the maximum spark length was reduced when in the box. A glass panel placed between the source of electromagnetic waves and the receiver absorbed ultraviolet radiation that assisted the electrons in jumping across the gap. When removed, the spark length would increase. He observed no decrease in spark length when he replaced glass with quartz, as quartz does not absorb UV radiation. Hertz concluded his months of investigation and reported the results obtained. He did not further pursue investigation of this effect.

The discovery by Hertz[23] in 1887 that the incidence of ultra-violet light on a spark gap facilitated the passage of the spark, led immediately to a series of investigations by Hallwachs,[24] Hoor,[25] Righi[26] and Stoletow.[27][28][29][30][31][32][33] on the effect of light, and especially of ultra-violet light, on charged bodies. It was proved by these investigations that a newly cleaned surface of zinc, if charged with negative electricity, rapidly loses this charge however small it may be when ultra-violet light falls upon the surface; while if the surface is uncharged to begin with, it acquires a positive charge when exposed to the light, the negative electrification going out into the gas by which the metal is surrounded; this positive electrification can be much increased by directing a strong airblast against the surface. If however the zinc surface is positively electrified it suffers no loss of charge when exposed to the light: this result has been questioned, but a very careful examination of the phenomenon by Elster and Geitel[34] has shown that the loss observed under certain circumstances is due to the discharge by the light reflected from the zinc surface of negative electrification on neighbouring conductors induced by the positive charge, the negative electricity under the influence of the electric field moving up to the positively electrified surface.[35]

With regard to the Hertz effect, the researches from the start showed a great complexity of the phenomenon of photoelectric fatigue — that is, the progressive diminution of the effect observed upon fresh metallic surfaces. According to an important research by Wilhelm Hallwachs, ozone played an important part in the phenomenon.[36] However, other elements enter such as oxidation, the humidity, the mode of polish of the surface, etc. It was at the time not even sure that the fatigue is absent in a vacuum.

In the period from February 1888 and until 1891, a detailed analysis of photoeffect was performed by Aleksandr Stoletov with results published in 6 works;[37][38][39][40][41][42] four of them in Comptes Rendus, one review in Physikalische Revue (translated from Russian), and the last work in Journal de Physique. First, in these works Stoletov invented a new experimental setup which was more suitable for a quantitative analysis of photoeffect. Using this setup, he discovered the direct proportionality between the intensity of light and the induced photo electric current (the first law of photoeffect or Stoletov's law). One of his other findings resulted from measurements of the dependence of the intensity of the electric photo current on the gas pressure, where he found the existence of an optimal gas pressure Pm corresponding to a maximum photocurrent; this property was used for a creation of solar cells.

In 1899, J. J. Thomson investigated ultraviolet light in Crookes tubes.[43] Thomson deduced that the ejected particles were the same as those previously found in the cathode ray, later called electrons, which he called "corpuscles". In the research, Thomson enclosed a metal plate (a cathode) in a vacuum tube, and exposed it to high frequency radiation.[44] It was thought that the oscillating electromagnetic fields caused the atoms' field to resonate and, after reaching a certain amplitude, caused a subatomic "corpuscle" to be emitted, and current to be detected. The amount of this current varied with the intensity and colour of the radiation. Larger radiation intensity or frequency would produce more current.

20th century

The discovery of the ionization of gases by ultra-violet light was made by Philipp Lenard in 1900. As the effect was produced across several centimeters of air and made very great positive and small negative ions, it was natural to interpret the phenomenon, as did J. J. Thomson, as a Hertz effect upon the solid or liquid particles present in the gas.[15]

In 1902, Lenard observed that the energy of individual emitted electrons increased with the frequency (which is related to the color) of the light.[6]

This appeared to be at odds with Maxwell's wave theory of light, which predicted that the electron energy would be proportional to the intensity of the radiation.

Lenard observed the variation in electron energy with light frequency using a powerful electric arc lamp which enabled him to investigate large changes in intensity, and that had sufficient power to enable him to investigate the variation of potential with light frequency. His experiment directly measured potentials, not electron kinetic energy: he found the electron energy by relating it to the maximum stopping potential (voltage) in a phototube. He found that the calculated maximum electron kinetic energy is determined by the frequency of the light. For example, an increase in frequency results in an increase in the maximum kinetic energy calculated for an electron upon liberation – ultraviolet radiation would require a higher applied stopping potential to stop current in a phototube than blue light. However Lenard's results were qualitative rather than quantitative because of the difficulty in performing the experiments: the experiments needed to be done on freshly cut metal so that the pure metal was observed, but it oxidised in a matter of minutes even in the partial vacuums he used. The current emitted by the surface was determined by the light's intensity, or brightness: doubling the intensity of the light doubled the number of electrons emitted from the surface.

The researches of Langevin and those of Eugene Bloch[45] have shown that the greater part of the Lenard effect is certainly due to this 'Hertz effect'. The Lenard effect upon the gas itself nevertheless does exist. Refound by J. J. Thomson[46] and then more decisively by Frederic Palmer, Jr.,[47][48] it was studied and showed very different characteristics than those at first attributed to it by Lenard.[15]

In 1905, Albert Einstein solved this apparent paradox by describing light as composed of discrete quanta, now called photons, rather than continuous waves. Based upon Max Planck's theory of black-body radiation, Einstein theorized that the energy in each quantum of light was equal to the frequency multiplied by a constant, later called Planck's constant. A photon above a threshold frequency has the required energy to eject a single electron, creating the observed effect. This discovery led to the quantum revolution in physics and earned Einstein the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.[49] By wave-particle duality the effect can be analyzed purely in terms of waves though not as conveniently.[50]

Albert Einstein's mathematical description of how the photoelectric effect was caused by absorption of quanta of light was in one of his 1905 papers, named "On a Heuristic Viewpoint Concerning the Production and Transformation of Light". This paper proposed the simple description of "light quanta", or photons, and showed how they explained such phenomena as the photoelectric effect. His simple explanation in terms of absorption of discrete quanta of light explained the features of the phenomenon and the characteristic frequency.

The idea of light quanta began with Max Planck's published law of black-body radiation ("On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum"[51]) by assuming that Hertzian oscillators could only exist at energies E proportional to the frequency f of the oscillator by E = hf, where h is Planck's constant. By assuming that light actually consisted of discrete energy packets, Einstein wrote an equation for the photoelectric effect that agreed with experimental results. It explained why the energy of photoelectrons was dependent only on the frequency of the incident light and not on its intensity: a low-intensity, high-frequency source could supply a few high energy photons, whereas a high-intensity, low-frequency source would supply no photons of sufficient individual energy to dislodge any electrons. This was an enormous theoretical leap, but the concept was strongly resisted at first because it contradicted the wave theory of light that followed naturally from James Clerk Maxwell's equations for electromagnetic behavior, and more generally, the assumption of infinite divisibility of energy in physical systems. Even after experiments showed that Einstein's equations for the photoelectric effect were accurate, resistance to the idea of photons continued, since it appeared to contradict Maxwell's equations, which were well-understood and verified.

Einstein's work predicted that the energy of individual ejected electrons increases linearly with the frequency of the light. Perhaps surprisingly, the precise relationship had not at that time been tested. By 1905 it was known that the energy of photoelectrons increases with increasing frequency of incident light and is independent of the intensity of the light. However, the manner of the increase was not experimentally determined until 1914 when Robert Andrews Millikan showed that Einstein's prediction was correct.[7]

The photoelectric effect helped to propel the then-emerging concept of wave–particle duality in the nature of light. Light simultaneously possesses the characteristics of both waves and particles, each being manifested according to the circumstances. The effect was impossible to understand in terms of the classical wave description of light,[52][53][54] as the energy of the emitted electrons did not depend on the intensity of the incident radiation. Classical theory predicted that the electrons would 'gather up' energy over a period of time, and then be emitted.[53][55]

Uses and effects

Photomultipliers

These are extremely light-sensitive vacuum tubes with a photocathode coated onto part (an end or side) of the inside of the envelope. The photocathode contains combinations of materials such as caesium, rubidium and antimony specially selected to provide a low work function, so when illuminated even by very low levels of light, the photocathode readily releases electrons. By means of a series of electrodes (dynodes) at ever-higher potentials, these electrons are accelerated and substantially increased in number through secondary emission to provide a readily detectable output current. Photomultipliers are still commonly used wherever low levels of light must be detected.[56]

Image sensors

Video camera tubes in the early days of television used the photoelectric effect, for example, Philo Farnsworth's "Image dissector" used a screen charged by the photoelectric effect to transform an optical image into a scanned electronic signal.[57]

Gold-leaf electroscope

Gold-leaf electroscopes are designed to detect static electricity. Charge placed on the metal cap spreads to the stem and the gold leaf of the electroscope. Because they then have the same charge, the stem and leaf repel each other. This will cause the leaf to bend away from the stem.

The electroscope is an important tool in illustrating the photoelectric effect. For example, if the electroscope is negatively charged throughout, there is an excess of electrons and the leaf is separated from the stem. If high-frequency light shines on the cap, the electroscope discharges and the leaf will fall limp. This is because the frequency of the light shining on the cap is above the cap's threshold frequency. The photons in the light have enough energy to liberate electrons from the cap, reducing its negative charge. This will discharge a negatively charged electroscope and further charge a positive electroscope. However, if the electromagnetic radiation hitting the metal cap does not have a high enough frequency (its frequency is below the threshold value for the cap), then the leaf will never discharge, no matter how long one shines the low-frequency light at the cap.[58]:389–390

Photoelectron spectroscopy

Since the energy of the photoelectrons emitted is exactly the energy of the incident photon minus the material's work function or binding energy, the work function of a sample can be determined by bombarding it with a monochromatic X-ray source or UV source, and measuring the kinetic energy distribution of the electrons emitted.[14]:14–20

Photoelectron spectroscopy is usually done in a high-vacuum environment, since the electrons would be scattered by gas molecules if they were present. However, some companies are now selling products that allow photoemission in air. The light source can be a laser, a discharge tube, or a synchrotron radiation source.[59]

The concentric hemispherical analyser (CHA) is a typical electron energy analyzer, and uses an electric field to change the directions of incident electrons, depending on their kinetic energies. For every element and core (atomic orbital) there will be a different binding energy. The many electrons created from each of these combinations will show up as spikes in the analyzer output, and these can be used to determine the elemental composition of the sample.

Spacecraft

The photoelectric effect will cause spacecraft exposed to sunlight to develop a positive charge. This can be a major problem, as other parts of the spacecraft in shadow develop a negative charge from nearby plasma, and the imbalance can discharge through delicate electrical components. The static charge created by the photoelectric effect is self-limiting, though, because a more highly charged object gives up its electrons less easily.[60][61]

Moon dust

Light from the sun hitting lunar dust causes it to become charged through the photoelectric effect. The charged dust then repels itself and lifts off the surface of the Moon by electrostatic levitation.[62][63] This manifests itself almost like an "atmosphere of dust", visible as a thin haze and blurring of distant features, and visible as a dim glow after the sun has set. This was first photographed by the Surveyor program probes in the 1960s. It is thought that the smallest particles are repelled up to kilometers high, and that the particles move in "fountains" as they charge and discharge.

Night vision devices

Photons hitting a thin film of alkali metal or semiconductor material such as gallium arsenide in an image intensifier tube cause the ejection of photoelectrons due to the photoelectric effect. These are accelerated by an electrostatic field where they strike a phosphor coated screen, converting the electrons back into photons. Intensification of the signal is achieved either through acceleration of the electrons or by increasing the number of electrons through secondary emissions, such as with a micro-channel plate. Sometimes a combination of both methods is used. Additional kinetic energy is required to move an electron out of the conduction band and into the vacuum level. This is known as the electron affinity of the photocathode and is another barrier to photoemission other than the forbidden band, explained by the band gap model. Some materials such as Gallium Arsenide have an effective electron affinity that is below the level of the conduction band. In these materials, electrons that move to the conduction band are all of sufficient energy to be emitted from the material and as such, the film that absorbs photons can be quite thick. These materials are known as negative electron affinity materials.

Cross section

The photoelectric effect is one interaction mechanism between photons and atoms. It is one of 12 theoretically possible interactions.[64]

At the high photon energies comparable to the electron rest energy of 511 keV, Compton scattering, another process, may take place. Above twice this (1.022 MeV) pair production may take place.[65] Compton scattering and pair production are examples of two other competing mechanisms.

Indeed, even if the photoelectric effect is the favoured reaction for a particular single-photon bound-electron interaction, the result is also subject to statistical processes and is not guaranteed, albeit the photon has certainly disappeared and a bound electron has been excited (usually K or L shell electrons at gamma ray energies). The probability of the photoelectric effect occurring is measured by the cross section of interaction, σ. This has been found to be a function of the atomic number of the target atom and photon energy. A crude approximation, for photon energies above the highest atomic binding energy, is given by:[66]

Here Z is atomic number and n is a number which varies between 4 and 5. (At lower photon energies a characteristic structure with edges appears, K edge, L edges, M edges, etc.) The obvious interpretation follows that the photoelectric effect rapidly decreases in significance, in the gamma ray region of the spectrum, with increasing photon energy, and that photoelectric effect increases steeply with atomic number. The corollary is that high-Z materials make good gamma-ray shields, which is the principal reason that lead (Z = 82) is a preferred and ubiquitous gamma radiation shield.[67]

See also

Electronics:

Physics:

- Anomalous photovoltaic effect

- Dember effect

- Photo-Dember

- Photomagnetic effect

- Corona discharge

- Photoelectron spectroscopy

- Planck's law of black body radiation

- Quantum mechanics

Chemistry:

- Photochemistry

- Electrochemistry

- Quantum Chemistry

- Silicon

- Boron

- Phosphorus

- Semi-conductor

- Metalloid

- Non-metal

- Ionization

- Crystallized atoms

Lists:

References

- 1 2 Serway, R. A. (1990). Physics for Scientists & Engineers (3rd ed.). Saunders. p. 1150. ISBN 0-03-030258-7.

- 1 2 Sears, F. W.; Zemansky, M. W.; Young, H. D. (1983). University Physics (6th ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 843–844. ISBN 0-201-07195-9.

- ↑ Hertz, H. (1887). "Ueber den Einfluss des ultravioletten Lichtes auf die electrische Entladung". Annalen der Physik 267 (8): S. 983–1000. Bibcode:1887AnP...267..983H. doi:10.1002/andp.18872670827.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1923". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2015-03-29.

- 1 2 Lenard, P. (1902). "Ueber die lichtelektrische Wirkung". Annalen der Physik 313 (5): 149–198. Bibcode:1902AnP...313..149L. doi:10.1002/andp.19023130510.

- 1 2 Millikan, R. (1914). "A Direct Determination of "h."". Physical Review 4 (1): 73–75. Bibcode:1914PhRv....4R..73M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.4.73.2.

- ↑ Millikan, R. (1916). "A Direct Photoelectric Determination of Planck's "h"" (PDF). Physical Review 7 (3): 355–388. Bibcode:1916PhRv....7..355M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.7.355.

- ↑ Zhang, Q. (1996). "Intensity dependence of the photoelectric effect induced by a circularly polarized laser beam". Physics Letters A 216 (1–5): 125. Bibcode:1996PhLA..216..125Z. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(96)00259-9.

- ↑ Bubb, F. (1924). "Direction of Ejection of Photo-Electrons by Polarized X-rays". Physical Review 23 (2): 137–143. Bibcode:1924PhRv...23..137B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.23.137.

- ↑ Mee, C.; Crundell, M.; Arnold, B.; Brown, W. (2011). International A/AS Level Physics. Hodder Education. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-340-94564-3.

- ↑ Fromhold, A. T. (1991). Quantum Mechanics for Applied Physics and Engineering. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-486-66741-6.

- ↑ Gautreau, R.; Savin, W. (1999). Schaum's Outline of Modern Physics (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-07-024830-3.

- 1 2 Hüfner, S. (2003). Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Principles and Applications. Springer. ISBN 3-540-41802-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Report of the Board of Regents By Smithsonian Institution. Board of Regents, United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution. p. 239.

- ↑ Schmidt, G. C. (1898) Wied. Ann. Uiv. p. 708.

- ↑ Knoblauch, O. (1899). Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie xxix. p. 527.

- ↑ Vesselinka Petrova-Koch; Rudolf Hezel; Adolf Goetzberger (2009). High-Efficient Low-Cost Photovoltaics: Recent Developments. Springer. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-3-540-79358-8.

- ↑ Smith, W. (1873). "Effect of Light on Selenium during the passage of an Electric Current". Nature 7 (173): 303. Bibcode:1873Natur...7R.303.. doi:10.1038/007303e0.

- ↑ Asimov, A. (1964) Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, Doubleday, ISBN ISBN 0-385-04693-6.

- ↑ Robert Bud; Deborah Jean Warner (1998). Instruments of Science: An Historical Encyclopedia. Science Museum, London, and National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-8153-1561-2.

- ↑ Elster and Geitel arrange the metals in the following order with respect to their power of discharging negative electricity: rubidium, potassium, alloy of potassium and sodium, sodium, lithium, magnesium, thallium and zinc. For copper, platinum, lead, iron, cadmium, carbon, and mercury the effects with ordinary light are too small to be measurable. The order of the metals for this effect is the same as in Volta's series for contact-electricity, the most electropositive metals giving the largest photo-electric effect.

- ↑ Hertz, Wied. Ann. xxxi. p. 983, 1887.

- ↑ Hallwachs, Wied. Ann. xxxiii. p. 301, 1888.

- ↑ Hoor, Repertorium des Physik, xxv. p. 91, 1889.

- ↑ Bighi, C. R. cvi. p. 1349; cvii. p. 559, 1888

- ↑ Stoletow. C. R. cvi. pp. 1149, 1593; cvii. p. 91; cviii. p. 1241; Physikalische Revue, Bd. i., 1892.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Sur une sorte de courants electriques provoques par les rayons ultraviolets". Comptes Rendus CVI: 1149. (Reprinted in Stoletow, M.A. (1888). "On a kind of electric current produced by ultra-violet rays". Philosophical Magazine Series 5 26 (160): 317. doi:10.1080/14786448808628270.; abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 605, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Sur les courants actino-electriqies au travers deTair". Comptes Rendus CVI: 1593. (Abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 723, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Suite des recherches actino-electriques". Comptes Rendus CVII: 91. (Abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 723, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1889). "Sur les phénomènes actino-électriques". Comptes Rendus. CVIII: 1241.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1889). "Актино-электрические исследовaния". Journal of the Russian Physico-chemical Society (in Russian) 21: 159.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1890). "Sur les courants actino-électriques dans l'air raréfié". Journal de Physique 9: 468. doi:10.1051/jphystap:018900090046800.

- ↑ Elster and Geitel, Wied. Ann. xxxviii. pp. 40, 497, 1889; xli. p. 161, 1890; xlii. p. 564, 1891; xliii. p. 225, 1892; lii. p. 433, 1894 ; lv. p. 684, 1895.

- ↑ Thomson, J. J. (2005). Conduction of Electricity Through Gases. Watchmaker Publishing. ISBN 978-1-929148-49-3. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ Hallwachs, W. (1907). "Über die lichtelektrische Ermüdung". Annalen der Physik 328 (8): 459–516. Bibcode:1907AnP...328..459H. doi:10.1002/andp.19073280807.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Sur une sorte de courants electriques provoques par les rayons ultraviolets". Comptes Rendus CVI: 1149. (Reprinted in Stoletow, M.A. (1888). "On a kind of electric current produced by ultra-violet rays". Philosophical Magazine Series 5 26 (160): 317. doi:10.1080/14786448808628270.; abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 605, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Sur les courants actino-electriques au travers deTair". Comptes Rendus CVI: 1593. (Abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 723, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1888). "Suite des recherches actino-électriques". Comptes Rendus CVII: 91. (Abstract in Beibl. Ann. d. Phys. 12, 723, 1888).

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1889). "Sur les phénomènes actino-électriques". Comptes Rendus. CVIII: 1241.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1889). "Актино-электрические исследовaния". Journal of the Russian Physico-chemical Society (in Russian) 21: 159.

- ↑ Stoletow, A. (1890). "Sur les courants actino-électriques dans l'air raréfié". Journal de Physique 9: 468. doi:10.1051/jphystap:018900090046800.

- ↑ The International Year Book. (1900). New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. p. 659.

- ↑ Buchwald, Jed; Warwick, Andrew, eds. (2004). Histories of the Electron: The Birth of Microphysics (PDF) (illustrated, reprint ed.). MIT Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9780262524247.

- ↑ Bloch, E. (1908). "L'ionisation de l'air par la lumière ultra-violette". Le Radium 5 (8): 240. doi:10.1051/radium:0190800508024001.

- ↑ Thomson, J. J. (1907). "On the Ionisation of Gases by Ultra-Violet Light and on the evidence as to the Structure of Light afforded by its Electrical Effects". Proc. Cambr. Phil. Soc. 14: 417.

- ↑ Palmer, Frederic (1908). "Ionisation of Air by Ultra-violet Light". Nature 77 (2008): 582–582. Bibcode:1908Natur..77..582P. doi:10.1038/077582b0.

- ↑ Palmer, Frederic (1911). "Volume Ionization Produced by Light of Extremely Short Wave-Length". Physical Review (Series I) 32: 1–22. Bibcode:1911PhRvI..32....1P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevSeriesI.32.1.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Lamb, Willis E.; Scully, Marlan O. (1968). "Photoelectric effect without photons, discussing classical field falling on quantized atomic electron" (PDF).

- ↑ Planck, Max (1901). "Ueber das Gesetz der Energieverteilung im Normalspectrum (On the Law of Distribution of Energy in the Normal Spectrum)". Annalen der Physik 4 (3): 553. Bibcode:1901AnP...309..553P. doi:10.1002/andp.19013090310.

- ↑ Resnick, Robert (1972) Basic Concepts in Relativity and Early Quantum Theory, Wiley, p. 137, ISBN 0471717029.

- 1 2 Knight, Randall D. (2004) Physics for Scientists and Engineers With Modern Physics: A Strategic Approach, Pearson-Addison-Wesley, p. 1224, ISBN 0805386858.

- ↑ Penrose, Roger (2005) The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe, Knopf, p. 502, ISBN 0-679-45443-8

- ↑ Resnick, Robert (1972) Basic Concepts in Relativity and Early Quantum Theory, Wiley, p. 138, ISBN 0471717029.

- ↑ Timothy, J. Gethyn (2010) in Huber, Martin C.E. (ed.) Observing Photons in Space, ISSI Scientific Report 009, ESA Communications, pp. 365–408, ISBN 978-92-9221-938-3

- ↑ Burns, R. W. (1998) Television: An International History of the Formative Years, IET, p. 358, ISBN 0-85296-914-7.

- ↑ Tsokos, K. A. (2010). Cambridge Physics for the IB Diploma (revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521138215.

- ↑ Weaver, J. H.; Margaritondo, G. (1979). "Solid-State Photoelectron Spectroscopy with Synchrotron Radiation". Science 206 (4415): 151–156. Bibcode:1979Sci...206..151W. doi:10.1126/science.206.4415.151. PMID 17801770.

- ↑ Lai, Shu T. (2011). Fundamentals of Spacecraft Charging: Spacecraft Interactions with Space Plasmas (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 9780691129471.

- ↑ "Spacecraft charging". Arizona State University.

- ↑ Bell, Trudy E., "Moon fountains", NASA.gov, 2005-03-30.

- ↑ Dust gets a charge in a vacuum. spacedaily.com, July 14, 2000.

- ↑ Evans, R. D. (1955). The Atomic Nucleus. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger. p. 673. ISBN 0-89874-414-8.

- ↑ Evans, R. D. (1955). The Atomic Nucleus. Malabar, Fla.: Krieger. p. 712. ISBN 0-89874-414-8.

- ↑ Davisson, C. M. (1965). Interaction of gamma-radiation with matter. pp. 37–78. Bibcode:1965abgs.conf...37D.

- ↑ Knoll, Glenn F. (1999). Radiation Detection and Measurement. New York: Wiley. p. 49. ISBN 0-471-49545-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Photoelectric effect. |

- AstronomyCast "http://www.astronomycast.com/2014/02/ep-335-photoelectric-effect/". AstronomyCast.

- Nave, R., "Wave-Particle Duality". HyperPhysics.

- "Photoelectric effect". Physics 2000. University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado.

- ACEPT W3 Group, "The Photoelectric Effect". Department of Physics and Astronomy, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ.

- Haberkern, Thomas, and N Deepak "Grains of Mystique: Quantum Physics for the Layman". Einstein Demystifies Photoelectric Effect, Chapter 3.

- Department of Physics, "The Photoelectric effect". Physics 320 Laboratory, Davidson College, Davidson.

- Fowler, Michael, "The Photoelectric Effect". Physics 252, University of Virginia.

- Go to "Concerning an Heuristic Point of View Toward the Emission and Transformation of Light" to read an English translation of Einstein's 1905 paper. (Retrieved: 2014 Apr 11)

- http://www.chemistryexplained.com/Ru-Sp/Solar-Cells.html

- Photo-electric transducers: http://sensorse.com/page4en.html

- "Photoelectric Effect". The Physics Education Technology (PhET) project. (Java)

- Fendt, Walter, "The Photoelectric Effect". (Java)

- "Applet: Photo Effect". Open Source Distributed Learning Content Management and Assessment System. (Java)

| ||||||||||||||||||

|