Photochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Photochemical carbon dioxide reduction harnesses solar energy to convert CO2 into higher-energy products. The chemical conversion of CO2 already occurs on an industrial scale in the manufacture of solvents such as formic acid, but photochemical reduction differs in that it relies on a renewable energy source, the sun. Because CO2 is a greenhouse gas, there is environmental interest in producing artificial systems that are efficient photocatalysts, but the low turn-over rates of current methods have prohibited wide-scale industrial application.

Overview

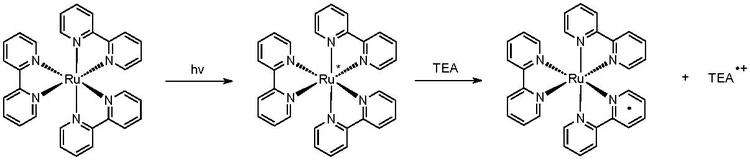

Photochemical reduction follows from chemical reduction (redox). But, it differs in that the electrons used for reduction are generated from the photoexcitation of another molecule, called a photosensitizer. To harness the sun's energy, the photosensitizer must be able to absorb light within the visible and ultraviolet spectrum. [1] Molecular sensitizers that meet this criterion often include a metal center, as the d-orbital splitting in organometallic species often falls within the energy range of far-UV and visible light. The reduction process begins with excitation of the photosensitizer, as mentioned. This causes the movement of an electron from the metal center into the functional ligands. This movement is termed a metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT). Back-electron transfer from the ligands to the metal after the charge transfer, which yields no net result, is prevented by including an electron-donating species in solution. Successful photosensitizers have a long-lived excited state, usually due to the interconversion from singlet to triplet states, that allow time for electron donors to interact with the metal center. [2] Common donors in photochemical reduction include triethylamine (TEA), triethanolamine (TEOA), and 1-benzyl-1,4-dihydronicotinamide (BNAH).

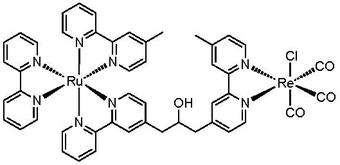

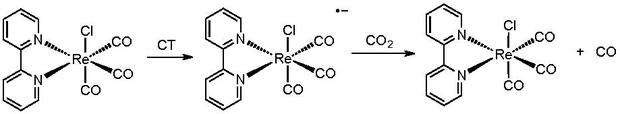

After excitation, CO2 coordinates or otherwise interacts with the inner coordination sphere of the reduced metal. The mechanistic details for this reduction process have not been fully determined, but commonly observed products include formate, formic acid, carbon monoxide, and methanol. Note that light absorption and catalytic reduction may occur at the same metal center or on different metal centers. That is, a photosensitizer and catalyst may be tethered through an organic linkage that provides for electronic communication between the species. In this case, the two metal centers form a bimetallic supramolecular complex. And, the excited electron that had resided on the functional ligands of photosensitizer passes through the ancillary ligands to the catalytic center, which becomes a one-electron reduced (OER) species. The advantage of dividing the two processes among different centers is in the ability to tune each center for a particular task, whether through selecting different metals or ligands.

History

Initial work by Lehn and Ziessel [4] in the 1980s led the development of catalytic CO2 reduction using visible light. In prior work developing photocatalysts for water splitting, Lehn observed that Co(I) species were produced in solutions containing CoCl2, 2,2'-bipyridine (bpy), a tertiary amine, and a Ru(bpy)3Cl2 photosensitizer. The high affinity of CO2 to cobalt centers led both he and Ziessel to study cobalt centers as electrocatalysts for reduction. In 1982, they reported CO and H2 as products from the irradiation of a solution containing 700ml of CO2, Ru(bpy)3 and Co(bpy).

Current Work

Since the work of Lehn and Ziessel, several catalysts have been paired with the Ru(bpy)3 photosensitizer. [5] When paired with methylviologen, cobalt, and nickel-based catalysts, carbon monoxide and hydrogen gas are observed as products. Paired with rhenium catalysts, carbon monoxide is observed as the major product, and with ruthenium catalysts formic acid is observed. It should be noted, however, that some product selection is attainable through tuning of the reaction environment. Other photosensitizers have also been employed as catalysts. They include FeTPP (TPP=5,10,15,20-tetraphenyl-21H,23H-porphine) and CoTPP, both of which produce CO while the latter produces formate also. Non-metal photocatalysts include pyridine and N-heterocyclic carbenes. [6] [7]

References

- ↑ Crabtree, R.-H.; “The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals, 4th ed.” John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2005. ISBN 978-0-471-66256-3

- ↑ Whitten, David G (1980). "Photoinduced Electron-Transfer Reactions of Metal Complexes in Solution". Accounts of Chemical Research 13: 83–90. doi:10.1021/ar50147a004.

- ↑ Gholamkhass, Bobak; Mametsuka, Hiroaki; Koike, Kazuhide; Tanabe, Toyoaki; Furue, Masaoki; Ishitani, Osamu (2005). "Architecture of Supramolecular Metal Complexes for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction: Ruthenium-Rhenium Bi- and Tetranuclear Complexes". Inorganic Chemistry 44: 2326–2336. doi:10.1021/ic048779r. PMID 15792468.

- ↑ Lehn, Jean-Marie; Ziessel, Raymond (1982). "Photochemical Generation of Carbon-Monoxide and Hydrogen by Reduction of Carbon-Dioxide and Water Under Visible-Light Irradiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 79 (2): 701–704. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.2.701.

- ↑ Fujita, Etsuko (1999). "Photochemical carbon dioxide reduction with metal complexes.". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 185-186: 373–384. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00023-5.

- ↑ Cole, Emily; Lakkaraju,Prasad; Rampulla,David; Morris, Amanda; Abelev, Esta; Bocarsly, Andrew (2010). "Using a One-Electron Shuttle for the Multielectron of CO2 to Methanol: Kinetic, Mechanistic, and Structural Insights.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 132: 11539–11551. doi:10.1021/ja1023496.

- ↑ Huang, Fang; Lu,Gang; Zhao,Lili; Wang,Zhi-Xiang (2010). "The Catalytic Role of N-Heterocyclic Carbene in a Metal-Free Conversion of Carbon Dioxide into Methanol: A Computational Mechanism Study.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 132: 12388–12396. doi:10.1021/ja103531z.

- ↑ Hawecker, Jeannot; Lehn,Jean-Marie; Ziessel, Raymond (1983). "Efficient Photochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO by Visible-Light Irradiation of Systems Containing Re(bipy)(CO)3X or Ru(bipy)32+-Co2+ Combinations as Homogeneous Catalysts.". Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications 9: 536–538. doi:10.1039/c39830000536.