Phi value analysis

Phi value analysis is an experimental protein engineering method used to study the structure of the folding transition state in small protein domains that fold in a two-state manner. Since the folding transition state is by definition a transient and partially unstructured state, its structure is difficult to determine by traditional methods such as protein NMR or X-ray crystallography. In phi-value analysis, the folding kinetics and conformational folding stability of the wild-type protein are compared with those of one or more point mutants. This comparison yields a phi value (defined below) that seeks to measure the mutated residue's energetic contribution to the folding transition state (and thus the degree of native structure around the mutated residue in the transition state) from the relative free energies of the unfolded state, the folded state and the transition state for the wild-type and mutant proteins.

Typically, a high fraction of the protein's residues are mutated one by one to identify clusters of residues that are well-ordered in the folded transition state. The interactions of these residues can be validated using double-mutant-cycle phi analysis, in which the effects of the single mutants are compared with those of the double mutant. In general, the mutations are conservative and replace the original residue with a smaller one (cavity-creating mutations), most commonly alanine; however, others such as tyrosine-to-phenylalanine, isoleucine-to-valine and threonine-to-serine mutations are also used. Examples of proteins that have been studied by phi value analysis include chymotrypsin inhibitor, SH3 domains, individual domains of proteins L and G, ubiquitin, and barnase.

Mathematical definition

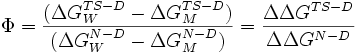

The phi value is defined as:[1]

where  represents the energy difference between the transition state and the denatured state for the wild-type protein,

represents the energy difference between the transition state and the denatured state for the wild-type protein,  represents this energy difference for the mutant protein, and the

represents this energy difference for the mutant protein, and the  terms represent the energy difference between the native state and the denatured state. Thus, the phi value represents the ratio of the energetic destabilization introduced by the mutation to the transition state versus that introduced to the native folded state.

terms represent the energy difference between the native state and the denatured state. Thus, the phi value represents the ratio of the energetic destabilization introduced by the mutation to the transition state versus that introduced to the native folded state.

The phi value should range from 0 to 1, but also negative phi values can be observed.[2] A phi value of 0 implies that the mutation has no effect on the structure of the rate-limiting transition state on the folding pathway, while a phi value of 1 indicates that the degree to which the transition state is destabilized by the mutation is exactly equal to the degree to which the folded state is destabilized. A phi value near 0 suggests that the region surrounding the mutation is relatively unfolded or unstructured in the transition state, while a value near 1 implies that the local structure around the mutation site in the transition state closely resembles the structure in the native state. It is generally the case that conservative substitutions on the surface of a protein yield phi values near 1. When the phi value is intermediate between 0 and 1, the method cannot directly distinguish between the alternative hypotheses that the transition state is partially structured, or that there are two populations of mostly-unfolded and mostly-folded states.

Key assumptions

Phi value analysis fundamentally assumes a close relationship between structure and energy. If the energy landscape has a well-defined and relatively deep global minimum, the resemblance of a folding intermediate structure to the native state may closely correlate with the energy of that structure. However, if the energy landscape is relatively flat or has many local minima, the relationship may not hold strongly enough for free energy destabilizations to provide useful structural information. The method also assumes that the folding pathway is not significantly altered, although the folding energies may be. For nonconservative mutations this assumption might be fundamentally flawed; thus conservative substitutions are preferred, though they may yield smaller energetic destabilizations that are thus more difficult to detect experimentally. Lastly, the restriction of the phi value range as necessarily nonnegative assumes that the introduction of a mutation will not increase the stability and thus lower the energy of either the native or the transition state relative to those of the wild-type protein. Also, it is implicitly assumed that the interactions that stabilize a folding transition state are native-like in nature. Many recent studies of protein folding, however, have suggested that stabilizing non-native interactions in a folding transition state may aid in folding. An elegant example of this is given in Zarrine-Afsar et al. (2008) PNAS, where authors have demonstrated that stabilizing non-native interaction in the Fyn SH3 domain actually accelerated the folding rate of this protein.

Example: barnase

Alan Fersht pioneered the phi value analysis method by first applying it to the small bacterial protein barnase.[3][4] In conjunction with molecular dynamics simulations, the analysis illustrated that, at least for this protein, the transition state between folding and unfolding is the same in both reaction directions and more closely resembled the native state. Phi values were found to vary considerably with the location of the mutation, with some regions of the protein yielding values near 0 and others yielding values near 1. The distribution of phi values over the protein agrees well with the simulated unfolding transition state in all but one helix, later identified as folding semi-independently and forming native-like contacts with the remainder of the protein only after the complete transition state has been reached. Such variations in the folding rate within a protein present another challenge in interpreting phi values, since the transition state structure cannot be determined experimentally. Folding and unfolding simulations, though computationally expensive, can provide valuable structural information that complements phi value results.

Variants of  -value analysis

-value analysis

Other kinetic-perturbation techniques for analyzing the folding transition state have been developed in recent years. The most well-known variant is the  -value,[5][6] in which two metal-binding residues such as histidine are engineered into a protein; the folding kinetics are then studied as a function of the metal ion concentration.[7] However, Fersht has illustrated some difficulties with this approach.[8] An alternative "cross-linking" variant of the

-value,[5][6] in which two metal-binding residues such as histidine are engineered into a protein; the folding kinetics are then studied as a function of the metal ion concentration.[7] However, Fersht has illustrated some difficulties with this approach.[8] An alternative "cross-linking" variant of the  -value was developed in the course of studying the association of segments in the folding transition state through the introduction of covalent crosslinks such as disulfide bonds.[9]

-value was developed in the course of studying the association of segments in the folding transition state through the introduction of covalent crosslinks such as disulfide bonds.[9]

Errors associated with  -value analysis

-value analysis

Experimental errors can be high in measuring equilibrium stability as well the folding/unfolding rates in water for the wild-type protein and mutants. The necessity of extrapolating phi values in pure water from measurements made in solutions containing denaturants adds uncertainty to the reported values. When the stability difference between the native and mutant protein are low (< 7 kJ/mol), experimental error can be very large; unusual phi-values outside the 0-1 range may arise from these errors rather than illustrating deviations from the conditions assumed by the method.[10] In addition, calculated phi values have been shown to depend strongly on the number of data points collected and the laboratory in which the experiment was performed.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Daggett V, Fersht AR. (2000). Transition states in protein folding. In Mechanisms of Protein Folding 2nd ed, editor RH Pain. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16142914

- ↑ Matouschek A, Kellis JT, Serrano L, Fersht AR. (1989). Mapping the transition state and pathway of protein folding by protein engineering. Nature 340:122. PMID 2739734

- ↑ Fersht AR, Matouschek A, Serrano L. (1992). The folding of an enzyme I. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J Mol Biol 224: 771. PMID 1569556

- ↑ Sosnick TR, Dothager RS and Krantz BA. (2004) Differences in the folding transition state of ubiquitin indicated by

and

and  analyses, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 17377-17382. PMID 15576508

analyses, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 17377-17382. PMID 15576508 - ↑ Krantz BA, Dothager RS and Sosnick TR. (2004) Discerning the Structure and Energy of Multiple Transition States in Protein Folding using

analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 337: 463-475. Erratum (2005): 347:1103. PMID 15003460

analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 337: 463-475. Erratum (2005): 347:1103. PMID 15003460 - ↑ Krantz BA and Sosnick TR. (2001) Engineered metal binding sites map the heterogeneous folding landscape of a coiled coil. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8: 1042-1047. PMID 11694889

- ↑ Fersht AR. (2004)

value versus

value versus  analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 17327-17328. PMID 15583125

analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 17327-17328. PMID 15583125 - ↑ Wedemeyer WJ, Welker E, Narayan M, Scheraga HA. (2000). Disulfide Bonds and Protein Folding. Biochemistry 39: 4207-4216; Erratum: 39: 7032. PMID 10841785

- ↑ Sanchez IE & Kiefhaber T (2003). Origin of unusual phi-values in protein folding: evidence against specific nucleation sites. J. Mol. Biol. 334: 1077-1085. PMID 14643667

- ↑ Miguel A. De Los Rios, B.K. Muraidhara, David Wildes, Tobin R. Sosnick, Susan Marqusee, Pernilla Wittung-Stafshede, Kevin W. Plaxco, & Ingo Ruczinski (2006). On the precision of experimentally determined protein folding rates and phi-values. Protein Science 15:553-563. PMID 16501226