Proteus (moon)

|

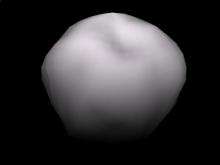

Voyager 2 image (1989) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

Voyager 2 Stephen P. Synnott |

| Discovery date | June 16, 1989 |

| Designations | |

| Adjectives | Protean |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| Epoch 18 August 1989 | |

| Periapsis | 117584±10 km |

| Apoapsis | 117709±10 km |

| 117647±1 km (4.75 RN) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.00053±0.00009 |

| 1.12231477±0.00000002 d | |

Average orbital speed | 7.623 km/s |

| Inclination |

0.524° (to Neptune equator) 0.026°±0.007° (to local Laplace plane) |

| Satellite of | Neptune |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 424 × 390 × 396 km[2][lower-alpha 1] |

| synchronous[2] | |

| zero[2] | |

| Albedo | 0.096[5][6] |

| Temperature | ≈ 51 K mean (estimate) |

| 19.7[5] | |

Proteus (/ˈproʊtiːəs/;[lower-alpha 3] Greek: Πρωτεύς), also known as Neptune VIII, is the second largest Neptunian moon, and Neptune's largest inner satellite. Discovered by Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1989, it is named after Proteus, the shape-changing sea god of Greek mythology. Proteus orbits Neptune in a nearly equatorial orbit at the distance of about 4.75 equatorial radii of the planet.

Despite being a predominantly icy body more than 400 km in diameter, Proteus's shape deviates significantly from an ellipsoid. It is shaped more like an irregular polyhedron with several slightly concave facets and relief as high as 20 km. Its surface is dark, neutral in color and heavily cratered. Proteus's largest crater is Pharos, which is more than 230 km in diameter. There are also a number of scarps, grooves, and valleys related to large craters.

Proteus is probably not an original body that formed with Neptune; it may have accreted later from the debris created when the largest Neptunian satellite Triton was captured.

Discovery and orbit

Proteus was discovered from the images taken by Voyager 2 space probe two months before its Neptune flyby in August 1989. It received the temporary designation S/1989 N 1.[7] Stephen P. Synnott and Bradford A. Smith announced its discovery on July 7, 1989, speaking only of "17 frames taken over 21 days", which gives a discovery date of sometime before June 16.[8]

On 16 September 1991 S/1989 N 1 was named after Proteus, the shape-changing sea god of Greek mythology.[9]

Proteus orbits Neptune at the distance approximately equal to 4.75 equatorial radii of the planet. Its orbit has a small eccentricity and is inclined by about 0.5° to the planet's equator.[1] Proteus is the largest of the regular prograde satellites of Neptune. It rotates synchronously with the orbital motion, which means that one face always points to the planet.[2]

Physical characteristics

Proteus is the second largest moon of Neptune. It is about 420 kilometres in diameter, larger than Nereid, the second to be discovered. It was not discovered by Earth-based telescopes because it is so close to Neptune that it is lost in the glare of reflected sunlight.[7] The surface of Proteus is dark—its geometrical albedo is about 10%. The color of its surface is neutral as the reflectivity does not change appreciably with the wavelength from violet to green.[7] In the near-infrared around 2 μm Proteus's surface becomes less reflective, pointing to a possible presence of complex organic compounds such as hydrocarbons or cyanides. These compounds may be responsible for the low albedo of the inner Neptunian moons. Although Proteus is usually thought to contain significant amounts of water ice, it has not been detected spectroscopically on the surface.[10]

The shape of Proteus is close to a sphere with a radius of about 210 km, although deviations from the spherical shape are large—up to 20 km; scientists believe it is about as large as a body of its density can be without being pulled into a perfect spherical shape by its own gravity.[4] Saturn's moon Mimas has an ellipsoidal shape despite being slightly less massive than Proteus, perhaps due to the higher temperature near Saturn or tidal heating.[4] Proteus is slightly elongated in the direction of Neptune, although its overall shape is closer to an irregular polyhedron than to a triaxial ellipsoid. The surface of Proteus shows several flat or slightly concave facets measuring from 150 to 200 km in diameter. They are probably degraded impact craters.[2]

Proteus is heavily cratered, showing no sign of any geological modification.[7] The largest crater, Pharos, has a diameter from 230 to 260 km.[4] Its depth is about 10–15 km.[2] The crater has a central dome on its floor a few kilometers high.[2] Pharos is the only named surface feature on this moon: the name is Greek and refers to the island where Proteus reigned.[11] In addition to Pharos there are several craters 50–100 km in diameter and many more with diameters less than 50 km.[2]

The second landform found on Proteus is linear features such as scarps, valleys and grooves. The most prominent one runs parallel to the equator to the west of Pharos. These features likely formed as a result of the giant impacts, which formed Pharos and other large craters or as a result of tidal stresses from Neptune.[2][4]

Origin

Proteus, like the other inner satellites of Neptune, is unlikely to be an original body that formed with it, and is more likely to have accreted from the rubble that was produced after Triton's capture. Triton's orbit upon capture would have been highly eccentric, and would have caused chaotic perturbations in the orbits of the original inner Neptunian satellites, causing them to collide and reduce to a disc of rubble.[12] Only after Triton's orbit became circularised did some of the rubble disc re-accrete into the present-day satellites.[13]

Gallery

-

.jpg)

Map of Proteus

-

Animated 3D model of Proteus with a superimposed mesh

-

Animated 3D model of Proteus

Notes

- ↑ In the earlier papers slightly different dimensions were reported. Thomas and Veverka in 1991 reported 440×416×404 km.[2][3] Croft in 1992 reported 430×424×410 km.[4] The difference is caused by the use of different sets of images and by the fact that the shape of Proteus is not described well by a triaxial ellipsoid.[2] </ref>Mean radius210±7 km[5]Volume (3.4±0.4)×107 km3[2]Mass 4.4×1019 kg[lower-alpha 2] 0.17 km/s<ref group='lower-alpha'>Escape velocity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r: √2Gm/r.

- ↑ The mass was calculated by multiplying the volume from Stooke (1994)[2] by the assumed density of 1,300 kg/m3. If one uses slightly larger dimensions from the earlier papers the mass will increase to 5×1019 kg.[5] </ref>Mean density≈ 1.3 g/cm³ (estimate)[5] 0.07 m/s2<ref group='lower-alpha'>Surface gravity derived from the mass m, the gravitational constant G and the radius r: Gm/r2.

- ↑ In US dictionary transcription, US dict: prō′·tē·əs.

References

- 1 2 Jacobson, R. A.; Owen, W. M., Jr. (2004). "The orbits of the inner Neptunian satellites from Voyager, Earthbased, and Hubble Space Telescope observations". Astronomical Journal 128 (3): 1412–1417. Bibcode:2004AJ....128.1412J. doi:10.1086/423037.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Stooke, Philip J. (1994). "The surfaces of Larissa and Proteus". Earth, Moon, and Planets 65 (1): 31–54. Bibcode:1994EM&P...65...31S. doi:10.1007/BF00572198.

- ↑ Williams, Dr. David R. (2008-01-22). "Neptunian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Croft, S. (1992). "Proteus: Geology, shape, and catastrophic destruction". Icarus 99 (2): 402–408. Bibcode:1992Icar...99..402C. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90156-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 2010-10-18. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Karkoschka, Erich (2003). "Sizes, shapes, and albedos of the inner satellites of Neptune". Icarus 162 (2): 400–407. Bibcode:2003Icar..162..400K. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00002-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Banfield, D.; Barnet, C.; Basilevsky, A. T.; Beebe, R. F.; Bollinger, K.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A. (1989). "Voyager 2 at Neptune: Imaging Science Results". Science 246 (4936): 1422–1449. Bibcode:1989Sci...246.1422S. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1422. PMID 17755997.

- ↑ Green, Daniel W. E. (July 7, 1989). "1989 N 1". IAU Circular 4806. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Marsden, Brian G. (September 16, 1991). "Satellites of Saturn and Neptune". IAU Circular 5347. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- ↑ Dumas, Christophe; Smith, Bradford A.; Terrile, Richard J. (2003). "Hubble Space Telescope NICMOS Multiband Photometry of Proteus and Puck". The Astronomical Journal 126 (2): 1080–1085. Bibcode:2003AJ....126.1080D. doi:10.1086/375909.

- ↑ "Proteus: Pharos". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ↑ Goldreich, P.; Murray, N.; Longaretti, P. Y.; Banfield, D. (1989). "Neptune's story". Science 245 (4917): 500–504. Bibcode:1989Sci...245..500G. doi:10.1126/science.245.4917.500. PMID 17750259.

- ↑ Banfield, Don; Murray, Norm (October 1992). "A dynamical history of the inner Neptunian satellites". Icarus 99 (2): 390–401. Bibcode:1992Icar...99..390B. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90155-Z.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Proteus (moon). |

- Proteus Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- Proteus page at The Nine Planets

- Proteus, A Moon Of Neptune on Views of the Solar System

- Ted Stryk's Proteus Page

- Neptune's Known Satellites (by Scott S. Sheppard)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

.ogv.jpg)