The Phantom Tollbooth

|

Milo and Tock on the front cover | |

| Author | Norton Juster |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Jules Feiffer |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | 1961 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 256 |

| ISBN | 978-0-394-82037-8 |

| OCLC | 299866174 |

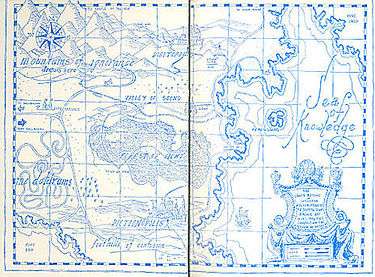

The Phantom Tollbooth is a children's adventure novel and modern fairy tale by Norton Juster. It was published in 1961 with illustrations by Jules Feiffer. It tells the story of a bored young boy named Milo who unexpectedly receives a magic tollbooth one afternoon and, having nothing better to do, decides to drive through it in his toy car. The tollbooth transports him to a land called the Kingdom of Wisdom. There he acquires two faithful companions, has many adventures, and goes on a quest to rescue the princesses of the kingdom—Princess Rhyme and Princess Reason—from the castle in the air. The text is full of puns, and many events, such as Milo's jump to the Island of Conclusions, exemplify literal meanings of English language idioms.

Juster claims his father's fondness for puns and The Marx Brothers' movies were a major influence.[1] Critics have compared its appeal to that of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, as well as L Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[2]

The book has been translated into several languages.[3]

History

In June 1960 Juster was given a $5,000 grant from the Ford Foundation to write a children's book about cities.[2] In his proposal, he said he wanted "to stimulate and heighten perception — to help children notice and appreciate the visual world around them — to help excite them and shape their interest in an environment they will eventually reshape."[4]

Juster quit his job so that he could work on the book. As part of it, he also took notes from an incident that had happened in Brooklyn a few days earlier, wanting to turn it into a short story.[5] A boy about 10 years old asked "What is the biggest number there is?" Juster stated that "when a kid asks you a question, you answer with another question, so I said, 'Tell me what you think the biggest number there is,'" and Juster repeatedly asked him to add one to the number the boy came up with, leading them to talk about infinity.[6] Juster, back in Brooklyn, wanted to finish the story about "a boy who asked too many questions" before returning to the book on cities.[5]

Around the time he met Feiffer (see below), he also met Judy Sheftel, a young editor whom he would marry in 1961.[7] She suggested that to pull the pieces together, that he write a two page synopsis. She later took the book to the editor Justin Epstein.[2] Epstein later wanted the whole section on Chroma and his orchestra removed,[8] but Juster insisted that it be kept.

The book was published in 1961. Juster says the book was rescued from the remainders table when Emily Maxwell wrote a rhapsodic review of it in The New Yorker magazine.[2]

Illustrations

Jules Feiffer, who did the drawings, had met Norton Juster some time earlier, and he, Juster, and a third man rented the building together, with Juster doing the cooking for all of them in return for using almost the whole fourth floor, with Feiffer and the other man on the third floor.[9] Feiffer was curious about the pacing going on above him (when Juster was writing), and decided to investigate. Juster showed him the early manuscripts. Feiffer liked it, and Juster continued showing Feiffer manuscript pages. Feiffer would draw sketches from the drafts of various sections of the book. There never was a formal agreement about the drawings: since Juster did the cooking, if Feiffer wanted to eat, he had to do the drawings.[7] Feiffer did not like to draw maps (Juster wanted a map) or horses. It became a game, with Feiffer trying to draw things the way he wanted, and Juster trying to describe things that were impossible to draw (such as the Triple Demons of Compromise). Juster says that Feiffer got his revenge by drawing him (Juster) as the Whether Man wearing a toga (Juster later wrote that he does not wear togas).[10]

Feiffer was in a panic as the book neared publication, since the text brought out his technical limitations as an artist, e.g. his inability to draw dogs or horses,[11] as well as the precedent of other illustrators such as Edward Ardizzone making him "question his suitability" as a children's book illustrator.[8] For instance, the drawing of the armies of wisdom has four riders on three horses (Feiffer originally drew them on cats instead of horses, and Juster was not amused).[12] Thinking he would have to do many revisions, he drew on cheap tracing paper, which began to disintegrate with time.[8] Later, Feiffer purportedly told himself, "Well, I got away with it."[8] He did consider the double-spread illustration of demons on pages 240–241 to be a success — a drawing which would later remain one of his favorites from the book, being different from his usual style (which would involve a white background), instead using Gustav Dore's drawings as an inspiration.[13]

Later editions

In 2011, a 50th anniversary edition was published (ISBN 978-0375869037), as well as The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth (see editions below) which includes sketches and copies of Juster's handwritten drafts and word lists, Feiffer's early drawings, and annotations by Leonard S. Marcus.

Plot

Milo is a boy bored by the world around him; every activity seems a waste of time. He arrives home from school one day to find in his bedroom a mysterious package that contains a miniature tollbooth and a map of "the Lands Beyond". Attached is a note addressed "FOR MILO, WHO HAS PLENTY OF TIME". He assembles the tollbooth, takes the map, drives through the tollbooth in his toy car, and instantly finds himself on a road to Expectations. He pays no attention to his route and soon becomes lost in the Doldrums, a colorless place where thinking and laughing are not allowed. However, he is found there and rescued by Tock, a "watchdog" with an alarm clock on him, who joins him on his journey.

Their first stop is Dictionopolis, one of two capital cities of the Kingdom of Wisdom. They visit the Word Market, where all the world's words and letters are bought and sold. After an altercation between the Spelling Bee and the blustering Humbug, Milo and Tock are arrested by the very short Officer Shrift. In prison, Milo meets the Which, (not to be confused with Witch), also known as Faintly Macabre. She tells him the history of Wisdom: Its two rulers, King Azaz the Unabridged and the Mathemagician, had two adopted younger sisters, Rhyme and Reason, to whom everyone came to settle disputes. All agreed that with Rhyme and Reason, nothing is impossible. Everyone lived in harmony until the rulers disagreed with the princesses' decision that letters and numbers were equally important. They banished the princesses to the Castle in the Air, and since then, the kingdom has had neither Rhyme nor Reason.

Milo and Tock leave the dungeon and attend a banquet given by King Azaz, where the guests literally eat their words. King Azaz allows Milo and the Humbug to talk themselves into a quest to rescue the princesses. Azaz appoints the Humbug as a guide, and he, Milo, and Tock set off for the Mathemagician's capital of Digitopolis (called "Numeropolis" in earlier drafts[14]) to obtain his approval for their quest.

Along the way they meet such characters as Alec Bings, a little boy who sees through things and grows until he reaches the ground, and have adventures like watching Chroma the Great conduct his orchestra in playing the colors of the sunset.

In Digitopolis, they meet the friendly Dodecahedron, who leads them to the Numbers Mine where numbers are dug out and precious stones are thrown away. They even eat subtraction stew, which makes the diner hungrier. (In the 2008 British Paperback edition, there is a recipe for Subtraction Stew. This is reprinted in p. 185 of The Annotated Phantom Tollbooth). To travel, the Mathemagician erases the mine with his magic pencil eraser. He and Milo discuss infinity, and Milo proves to the Mathemagician that he must allow them to rescue the princesses.

In the Mountains of Ignorance, the three intrepid journeyers contend with lurking, obstructionist demons like the Terrible Trivium and the Senses Taker. After overcoming various obstacles and their own fears, the questers reach the Castle in the Air. The two princesses welcome Milo and agree to return to Wisdom. When the group leaves, Tock carries them through the sky because, after all, time flies. The demons chase them, but the armies of Wisdom repel them. The armies of Wisdom welcome the princesses home, King Azaz and the Mathemagician are reconciled, and all enjoy a three-day carnival celebration of the return of Rhyme and Reason, the princesses of the land.

Milo says goodbye and drives off, feeling he has been away several weeks. Ahead in the road he spots the tollbooth and drives through. Suddenly he is back in his own room, and discovers he has been gone only an hour.

He awakens the next day full of plans to return to Wisdom, but when he returns from school the tollbooth has vanished. A new note has arrived, which reads, "FOR MILO, WHO NOW KNOWS THE WAY." It states that the tollbooth, revealed to be called 'The Phantom Tollbooth', is now being sent off to another child. Milo is somewhat disappointed but looks around and finds that he lives in a beautiful and interesting world, and decides if he ever finds a way back, he might not even have the time, because he has learned that there was so much to do right where he was.

Characters

Main characters

- Milo, a school-aged boy, the main character, bored with life prior to receiving the gifts. Milo's age is not stated. In early drafts, Juster put Milo's age at eight, then nine, before concluding that it was "not only unnecessary to be that precise but probably more prudent not to do so, lest some readers decide they were too old to care...".[11] A very early draft has him named "Tony" being ten years old with his parents "Mr. & Mrs. Flanders"[14]

- Tock, a "watchdog" (with an alarm-clock in his body) who befriends Milo after saving him from the Doldrums. Tock was based on one of Juster's favorite characters, Jim Fairfield from Jack Armstrong, the All-American Boy.[15]

- The Humbug, a pompous insect who joins Milo and Tock on their quest. Juster said, "For the sake of balance, I wanted someone who was the reverse [of Tock]— a bad influence, someone who is a braggart, not very honest, a huckster, not too trustworthy, a self promoter—in short, someone sure to steer Milo wrong."[16]

Minor Characters

- King Azaz the Unabridged, the King of Dictionopolis, one of the two rulers of Wisdom.

- The Mathemagician, Azaz's brother and the other ruler of Wisdom. He rules the city of Digitopolis.

- Faintly Macabre, (or Aunt Faintly), the Not-So-Wicked Which. When she regulated all words used in public, she became so stingy with them that people became afraid to talk at all. She tells Milo that she can be released from the dungeon with the return of Rhyme and Reason. (She isn't seen at the end of the book, so whether she was released or not is never resolved.) Also Juster's comment "witches hate loud noises" was only a plot device that he made up.[17]

- Chroma, conductor of an orchestra that plays all the world's colors. Feiffer's drawing of Chroma was loosely modelled on Arturo Toscanini[18]

- Dr. Kakofonous A. Dischord, a scientist who enjoys creating unpleasant sounds, and curing pleasant sounds. Feiffer's illustration of him bears a striking resemblance to Groucho Marx as Dr. Hugo Z. Hackenbush.[19]

- The Awful DYNNE ("awful din"), a genie who collects noises for Dr. Dischord.

- The Soundkeeper, who loves silence, rules the Valley of Sound. Her vaults keep all the sounds ever made in history.

- The Dodecahedron, an inhabitant of Digitopolis with twelve faces, each of which shows a different emotion. Originally Juster had J. Remington Rhomboid as the Mathemagician's assistant[20] a two-dimensional character with no depth, who would have become three-dimensional as a reward[21]

- Officer Shrift, a very short man, the police force of Dictionopolis.

- The Lethargarians, lethargically small, mischievous creatures who live in the Doldrums and are irresponsibly lazy.

- The Spelling Bee, an expert speller, but sometimes an enemy of the Humbug.

- The .58, a boy who is only .58 of a person from an "average" family, which has 2.58 children.

- Canby (can be), a frequent visitor to the Island of Conclusions, who is as much "as can be" of any possible quality. Play on the words "can be".

- King Azaz's advisors: the Duke of Definition, Minister of Meaning, Count of Connotation, Earl of Essence, and the Undersecretary of Understanding, all of which have the same (or almost the same) meaning.

- The Whether Man, who deals with whether there will be weather, rather than the specific nature of the weather. Note that Feiffer drew Juster as the Whether Man.[10]

- Alec Bings, a boy of Milo's age and weight who sees through things. He grows downwards from a fixed point in the air until he reaches the ground, unlike Milo, who grows upwards from the ground.

- The Everpresent Wordsnatcher, a dirty bird that "takes the words right out of your mouth". He is not a demon, just a nuisance. Juster considered naming him the "red crested word snatcher".[22]

- The Terrible Trivium, a demon in the Mountains of Ignorance who wastes time with useless - or "trivial" - jobs. Leonard Marcus observes that The Phantom Tollbooth itself was a procrastinatory diversion and that it's fitting that this occupies the place of pride as the first demon in the rogues' gallery of demons.[23]

- The Demon of Insincerity, a misleading demon who never says what he means.

- The Gelatinous Giant, a demon who blends in with his surroundings and is afraid of everything, mostly ideas.

- The Triple Demons of Compromise, one short and fat, one tall and thin, and one exactly like the other two. Norton gave these a cameo role just to describe something impossible to draw for Jules Feiffer.[10] These were, in notes, originally the Twin Demons of Compromise[24]

- The Senses Taker ("census taker"), a demon who robs Milo, the Humbug, and Tock of their senses by wasting their time and asking useless questions. Feiffer's illustration was an experiment using spattered ink, later used by Gerald Scarfe and Ralph Steadman a few years later.[25]

- Rhyme and Reason two princesses who settled disputes. The kings banished them to the Castle in the Air, thus being Milo's MacGuffin. They explain to Milo the reason why he has to study things. Both Feiffer and Juster were dissatisfied with the portrayals of Rhyme and Reason, Feiffer thought they looked too much like beauty pageant girls, and Juster thought they were "too much like the girls in my classes in elementary school — well behaved, responsible, orderly, a force for good, but a damper on the chaos I thrived on as a child."[26]

Unused Characters

In Juster's notes and drafts, there are a number of characters for which Juster had sketched, but did not use in the final drafts:

- The doorman, who received the package of the tollbooth[14]

- The small wild eyed little man who kept breathlessly repeating "It's here, it's here" who in early drafts, brought the tollbooth package to the doorman.[14] In the final draft, it is not known who brought the tollbooth, or who sent the tollbooth.

- Mr. and Mrs. Flanders, the parents of Tony (the protagonist's name in early drafts).[14] Tony later became Milo, the latter's age and last name never said. Milo's parents do not appear.

- The Chocolate Moose, who is always afraid he is not light enough[27]

- The Star Gazer, who wonders about everything[27]

- The Seal of Approval[27] which was to be one of the princesses' pets.[20]

- The Social Lion[27] Another which was to be one of the princesses' pets,[20] with a pun about "reading between the lions".[28]

- The Inventor, who never leaves well enough alone and invents improvements or things that have no use e.g. straight bananas and square oranges for easy packing in a spherical car, etc.[29]

- The Hitch-Hiker who always leads Milo into doing things the easy way and jumping to conclusions[29]

- The Optometrist, who fits the rose colored glasses[29]

- The Facsimile, who can be just like everyone else[29]

- Peter Paradox, an assistant to the Mathemagician[20]

- The Adding Machine, a robot assistant to the Mathemagician [20]

Critical reaction

Critics have acknowledged that the book is advanced for most children, who would not understand all the wordplay or the framing metaphor of the achievement of wisdom.[30][31] Writers like the reviewer in The New York Times have focused on the children and adults able to appreciate it; for them, it has "something wonderful for anybody old enough to relish the allegorical wisdom of Alice in Wonderland and the pointed whimsy of The Wizard of Oz".[32]

The Phantom Tollbooth is now acknowledged as a classic of children’s literature.[33] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Education Association named it one of "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children".[34] In 2012 it was ranked number 21 among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal.[35]

Awards

- Kansas William White Master List WINNER 1963[36]

- Scholastic Parent & Child 100 Greatest Books for Kids WINNER 2012[36]

- TimeOutNewYorkKids.com 50 Best Books for Kids WINNER 2012[36]

- Parents’ Choice Classic Award WINNER 2011[37]

- George C. Stone Centre For Children’s Books Award[38]

Adaptations

- Animation director Chuck Jones adapted the book into The Phantom Tollbooth, a feature live-action/animated film of the same name, in 1970. However, Juster stated that he disliked it.

- In 1995, Juster adapted Tollbooth into a libretto for an opera.

- Various stage adaptations have been created and performed. In 1977, a two-act play by Susan Nanus was published. The musical adaptation, with a score by Arnold Black and lyrics by Juster and Sheldon Harnick, premiered in 1995. In 2004, The Phantom Tollbooth was adapted as an official theatrical screenplay by Patrick Sayre and Cole Taylor.

- In 1987, composer Robert Xavier Rodriguez adapted a chapter of The Phantom Tollbooth into "A Colorful Symphony" for narrator and orchestra.

- In 2008, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts launched a 6-month tour of a children's theater adaptation of The Phantom Tollbooth.

- In February 2010, director Gary Ross began development of a remake of The Phantom Tollbooth under Warner Bros. with the first draft of the script written by Alex Tse.[39] As of August 2014, this has yet to come to pass.

In popular culture

- A Harry Turtledove short story about an alternate history WWII where Fyodor Tolbukhin leads Russian partisans against the occupying German forces is named "The Phantom Tolbukhin" in a play on Juster's book.

- In the first episode of the third season of the Sam & Max games, Sam mentions that they had "wasted too much time poking around that tollbooth."

- In episode two of the first season of Parks and Recreation, Amy Poehler's character Leslie Knope starts reading The Phantom Tollbooth to filibuster her own meeting.

- In episode 13 of New Girl, Schmidt states that The Phantom Tollbooth is one of his desert-island books. Cece says that she also loves the book, to which Schmidt replies, "Of course you do. You're a human being."

- In Bloom County: The Complete Digital Library, Volume One, creator Berke Breathed states that "Milo Bloom's name came from the hero of The Phantom Tollbooth, the first book I ever loved".

- The science fiction novel "The Phantom Stethoscope: A Field Manual for Finding An Optimistic Future in Medicine", by Stephen K. Klasko, MD paraphrases the title and features characters with similar names to the original characters.

References

- ↑ Dobbs Ferry Middle School Production of The Phantom Tollbooth press release from Dobbs Ferry Union Free School District website

- 1 2 3 4 Golpnik, Adam. "Broken Kingdom, Fifty Years of the Phantom Tollbooth". New Yorker Magazine. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- ↑ An Interview with Norton Juster, Author of The Phantom Tollbooth by Rosetta Stone from The Purple Crayon

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. ix

- 1 2 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. x

- ↑ Marcus, Leonard S., Funny Business, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA, 2009, pp. 129–130

- 1 2 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. xxiv

- 1 2 3 4 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. xxxiii

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth, p. xiii

- 1 2 3 Phantom Tollboth, 50th Anniversary Edition p. xi

- 1 2 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. xxxii

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 243

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 240

- 1 2 3 4 5 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. xxxi

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollboothp. 28

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 53

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollboothp. 66

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 120

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 136

- 1 2 3 4 5 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 267

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p.171

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 204

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 208

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollboothp. 213

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 225

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 231

- 1 2 3 4 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth, p. 259

- ↑ Annotated Phantom Tollbooth p. 230

- 1 2 3 4 Annotated Phantom Tollbooth, p. 260

- ↑ Saturday Review 45, no. 3 (20 January 1962): 27.

- ↑ Mathews, Miriam. Library Journal (15 January 1962): 84.

- ↑ McGovern, Ann. “Journey to Wisdom.” The New York Times, November 12, 1961, p. BRA35

- ↑ Jays, David. "Classic of the Month: The Phantom Tollbooth". The Guardian (London, England) (31 March 2004): 17.

- ↑ "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". National Education Association (nea.org). 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ↑ Bird, Elizabeth (July 7, 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- 1 2 3 http://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/89124/the-phantom-tollbooth-by-norton-juster-illustrated-by-jules-feiffer/

- ↑ http://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/208917/the-phantom-tollbooth-50th-anniversary-edition-by-norton-juster-illustrated-by-jules-feiffer/

- ↑ http://www.homeschoolshare.com/phantom_tollbooth.php

- ↑ Billington, Alex (February 17, 2010). "Gary Ross Bringing Phantom Tollbooth Back to the Big Screen". FirstShowing.net (First Showing, LLC). Retrieved April 12, 2010.

Editions

- Juster, Norton (1996). The Phantom Tollbooth, 35th Anniversary Edition. Knopf.

- Juster, Norton (2011). The Phantom Tollbooth, 50th Anniversary Edition. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-37586-903-7.

- Juster, Norton (2014). The Phantom Tollbooth,Essential Modern classics. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-37586-903-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Phantom Tollbooth |

- "The road to Dictionopolis", interview with Norton Juster from Salon.com

- Excerpts from the Phantom Tollbooth

- The Phantom Tollbooth at the Internet Movie Database

- Musical version by Sheldon Harnick and Arnold Black - Guide to Musical Theatre

- "Broken Kingdom: Fifty years of “The Phantom Tollbooth”" -(The New Yorker)