Petrus Camper

| Petrus Camper | |

|---|---|

|

Petrus Camper | |

| Born |

11 May 1722 Leiden |

| Died |

7 April 1789 The Hague |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Fields |

anatomist physiologist philosopher surgeon (dissection) Draughtsman |

| Institutions | University of Franeker, Amsterdamse Atheneum, University of Groningen |

| Alma mater | University of Leiden, Oxford College |

| Doctoral students | Martin van Marum |

| Known for | inventing the term "extinct" along with Georges Cuvier to describe the mammoth |

Peter, Pieter, or usually Petrus Camper (11 May 1722 – 7 April 1789), was a Dutch physician, anatomist, physiologist, midwife, zoologist, anthropologist, paleontologist and a naturalist. He studied the orangutan, the rhinoceros, and the skull of a mosasaur, which he believed was a whale. One of the first to interest himself in comparative anatomy and paleontology, he also invented the measure of the facial angle. Camper was not a dull professor in his library, becoming a celebrity in Europe and a member of the Royal Society. He was interested in architecture, mathematics, and made drawings for his lectures. He designed and made tools for his patients, always trying to be practical. Besides he was a sculptor, a patron of art and a conservative politician.

Studies and teaching

Camper was the son of a local well-to-do minister, who made his fortune in the East Indies. As a brilliant alumnus, he studied in the University of Leiden both medicine and philosophy, and got a degree in both sciences on the same day at the age of 24. His professors included Pieter van Musschenbroek and Willem Jacob 's Gravesande for physics and mathematics, Herman Boerhaave and Hieronymus David Gaubius for medicine, and François Hemsterhuis for philosophy. After both his parents died Camper then traveled in 1748 to Prussia, England (where he met with William Smellie), France and Switzerland. He was offered sundry professorships, being first named professor of philosophy, anatomy and surgery in 1750 at the University of Franeker. Camper married Johanna Bourboom in 1756, the daughter of the burgomaster of Leeuwarden, whom he had met in 1754 while treating her husband, the burgomaster from Harlingen, who died the same year he married her.[1]

Surgeon's Guild

Starting in 1755, he resided in Amsterdam where he occupied a chair of anatomy and surgery at the Athenaeum Illustre, later completed by a medicine chair. He investigated inguinal hernia, patella and the best form of shoe. He withdrew five years later to dedicate himself to scientific research and lived on his property just outside Franeker. In 1762 he became politically active in Groningen,in particular with regard to public health issues such as vaccination against smallpox. He also introduced several new instruments and operationprocedures for surgery and obstetrics and became focused on the problem of the head of the baby getting stuck during birth. In 1763 he chose to accept the chair of anatomy, surgery and botanics at the University of Groningen.[2]

Both in Amsterdam and in later years, Camper kept a surgical clinic and showed selfmade drawings to illustrate his eloquent lectures, before retiring in 1773. His main focus of attention was for anatomy, zoology and his collection of minerals and fossils. Among his many works, he studied osteology of birds and discovered the presence of air in the inner cavities of birds' skeletons. He investigated the anatomy of eight orangutans, and claimed it was a different species from the human being, and not simply a "degenerate" type of (white) human, as some contemporary scientists theorized. Petrus Camper published memoirs on the hearing of fishes and the sound of frogs, and dissected an elephant, and a rhinoceros from Java. He studied the diseases of rinderpest and rabies.

- He was visited by Samuel Thomas von Sömmering, who later became a professor in Göttingen.

- He became an associate of the French Academy of Sciences and had a eulogy in his honour composed by Nicolas de Condorcet and Félix Vicq-d'Azyr.

- In 1776 he became involved in a plan of dike construction.

- In 1780 he took lessons from Étienne Maurice Falconet.

- In November 1783 he was a Foreign Founding Member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh[3]

- In his ideas about art Camper was influenced by Johann Joachim Winckelmann.

- He made drawings of the Dolmen south of Groningen.

- He was in the selection committee for the prize contest for the design of the new townhall in Groningen that was later awarded to his friend Jacob Otten Husly, who he knew from his work for the Amsterdam Drawing Academy.

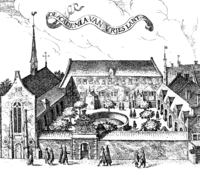

- He became one of the directors of the Admiralty of Friesland.

- He was appointed as an (Orangist) burgomaster of Workum in 1783, opposing the Patriots (faction).

- In September 1787 he became the president of the state council of the Dutch Republic and warmly welcomed the stattholder William V of Orange and his wife Wilhelmine of Prussia.

- At the end of life he suffered from pleuritis; Camper drank a good glass of champagne and died.

Comparative anatomy

One of the first scholar to study comparative anatomy, Petrus Camper demonstrated the principle of correlation in all organisms by the mechanical exercise he called a "metamorphosis". In his 1778 lecture, "On the Points of Similarity between the Human Species, Quadrupeds, Birds, and Fish; with Rules for Drawing, founded on this Similarity," he metamorphosed a horse into a human being, thus showing the similarity between all vertebrates. Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1884) theorized this in 1795 as the "unity of organic composition," the influence of which is perceptible in all his subsequent writings; nature, he observed, presents us with only one plan of construction, the same in principle, but varied in its accessory parts. Camper's metamorphoses which demonstrated this "unity of Plan" greatly impressed Diderot and Goethe. In 1923 and 1939 some Dutch authors suggested that Camper foreshadowed Goethe's famous idea of "type" — a common structural pattern in some manner[4]

"Facial angle"

Petrus Camper is also known for his theory of the "facial angle" originally in connection with two lectures he gave in Amsterdam in 1770 to art students on beauty and portraiture. He was concerned with the fact that all artists painted the black Magus in the nativity with Caucasian face. He determined that modern humans had facial angles between 70° and 80°, with African and Asian angles closer to 70°, and European angles closer to 80. According to his new portraiture technique, an angle is formed by drawing two lines: one horizontally from the nostril to the ear; and the other perpendicularly from the advancing part of the upper jawbone to the most prominent part of the forehead. He claimed that antique Greco-Roman statues presented an angle of 100°-95°, Europeans of 80°, 'Orientals' of 70°, Black people of 70° and the orangutan of 42-58°, but not in an overtly racist fashion-he merely claimed that, out of all human races, Africans were most removed from the Classical sense of ideal beauty. These results were later used as scientific racism, with research continued by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772–1844) and Paul Broca (1824–1880).

Camper, however, agreed with Buffon in drawing a sharp line between human and animals (although he was misinterpreted by Diderot, who claimed that he was a supporter of the Great Chain of Being theory).[5]

Legacy

Georges Cuvier (1769–1832) praised his "genius eye" but criticized him for keeping himself to simple sketches ("Camper porta, pour ainsi dire en passant, le coup d'œil du génie sur une foule d'objets intéressants, mais presque tous ses travaux ne furent que des ébauches").

His son Adriaan Gilles also became a scientist and published much of his father's unpublished research in addition to a biography of him.[6]

In 1888, the son of the last female descendant of Petrus Camper petitioned the Dutch crown for a name change to honor his mother, Theodora Aurelia Louisa Camper (1821–1890). The petition was granted by Royal Decree No. 15; and the descendants of Abraham Adriaan Aurelius Gerard Camper-Titsingh Sr. (1845–1910) and Abraham Adriaan Aurelius Gerard Camper-Titsingh Jr. (1889–1974) live today in the United States.[7]

The Dutch author, Thomas Rosenboom, used Petrus Camper as a character in his novel, Gewassen vlees (1994).[8]

Works

- Demonstrationes anatomico- pathologicae [1760–1762]

- Dissertation sur les différences des traits du visage and Discours sur l'art de juger les passions de l'homme par les traits de son visage

- On the Best Form of Shoe

- Two lectures to the Amsterdam Drawing society on the facial angle (1770)

- On the Points of Similarity between the Human Species, Quadrupeds, Birds, and Fish; with Rules for Drawing, founded on this Similarity (1778)

- Historiae literariae cultoribus S.P.D. Petrus Camper. A list of his work, published by himself.

- Works by Petrus Camper, the French compilation of Camper's work, based on Camper's French lecture notes and the posthumous publications by his son A.G. Camper, published and partially translated by Hendrik Jansen in 1803 in three octavo volumes.[9][10]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Friesian society notes on Petrus Camper's period in Friesland, by P.C.J.A. Boeles

- ↑ Studying in Groningen Through the Ages: A History of the University of Groningen and the First English Department in the Netherlands. Groningen: Groningen University Press, 2014, p. 87-88. ISBN 978-90-367-7125-2

- ↑ https://www.royalsoced.org.uk/cms/files/fellows/biographical_index/fells_indexp1.pdf

- ↑ See Miriam Claude Meijer, ""Petrus Camper's Protean Performances: The Metamorphoses" here at the Wayback Machine (archived October 22, 2009) (with a drawing of Camper's animated metamorphose) – URL accessed on February 28, 2007 (English)

- ↑ Ann Thomson, Issues at stake in eighteenth-century racial classification, Cromohs, 8 (2003): 1–20 (English)

- ↑ "Levensschets van P. Camper", by Adriaan Gilles camper, Leeuw, 1791.

- ↑ Nederland's Patriciaat, Vol. 13 (1923).

- ↑ Rosenboom, Thomas. (2004). Gewassen vlees.

- ↑ Oeuvres de Pierre Camper, qui ont pour objet l'histoire naturelle, la physiologie et l'anatomie comparée, Paris, 1803, Volume 2 on Google books

- ↑ Oeuvres de Pierre Camper, qui ont pour objet l'histoire naturelle, la physiologie et l'anatomie comparée, Paris, 1803, Volume 3 on Google books

- ↑ "Author Query for 'Camper'". International Plant Names Index.

References

- Bouillet, Marie-Nicolas Bouillet and Alexis Chassang. (1878). Dictionnaire universel d'histoire et de géographie.

- Meijer, Miriam Claude. "Petrus Camper's Protean Performances: The Metamorphoses" (English)

- Rosenboom, Thomas. (2004). Gewassen vlees. Amsterdam: Querido. ISBN 90-214-7988-5

- Thomson, Ann. Issues at Stake in Eighteenth-century Racial Classification, Cromohs, 8 (2003): 1–20 (English)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "article name needed". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- Studying in Groningen Through the Ages: A History of the University of Groningen and the First English Department in the Netherlands. Groningen: Groningen University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-90-367-7125-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petrus Camper. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Peter Camper. |

- http://www.whonamedit.com/doctor.cfm/3231.html

- Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

- University of Groningen on Camper

- Author page in the DBNL

|

.jpg)