Peruvian spider monkey

| Peruvian spider monkey[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Atelidae |

| Genus: | Ateles |

| Species: | A. chamek |

| Binomial name | |

| Ateles chamek (Humboldt, 1812) | |

| |

| Peruvian Spider Monkey range | |

The Peruvian spider monkey (Ateles chamek) also known as the Black-faced black spider monkey, is a species of spider monkey that lives not only in Peru, but also in Brazil and Bolivia. At two feet (0.6 m) long, they are relatively large among species of monkey, and their strong, prehensile tails can be up to three feet (1 m) long. Unlike many species of monkey, they have only a vestigial thumb, an adaptation which enables them to travel using brachiation.[3] Peruvian spider monkeys live in groups of 20-30 individuals, but these groups are rarely all together simultaneously. The size and dynamics of the resulting subgroups vary with food availability and sociobehavioral activity.[2] They prefer to eat fleshy fruit, but will change their diet in response to scarcity of ripe fruit.[4] Individuals of this species also eat small animals, insects and leaves based on availability. Females separate from the band to give birth, typically in the fall. These females inhabit a group of core areas where resources are abundant in certain seasons.[2] Typically, males exhibit ranging over longer distances than females, with movement of individuals enhancing the fluidity of subgroup size. Peruvian spider monkey are independent at about 10 months, with a lifespan of about 20 years.[2]

Characteristics

The Peruvian spider monkey weighs up to 20 pounds (9 kg.).[5] Its body can be 24 inches (0.7 m) long and the tail can be 36 inches (1 m)long. It has four elongated fingers and virtually no thumb, which is typical for spider monkeys but unusual for other monkeys. It can move easily through the trees and it uses its tail like an extra limb in a type of locomotion known as brachiation. It has an agility that can only be compared to the gibbon of Asia. It has a life span of up to 20 years.[6]

Distribution

The range of the Peruvian spider monkey is not limited to Peru but also includes Bolivia and Brazil.[7] They live primarily in lowland forests, occupying the canopy and the sub-canopy, but they have been observed using various habitat types.[8] They live in territorial bands of 6-12 individuals whose territory covers about 20 square kilometers.[5] Band size is somewhat seasonal,[9] probably because females separate themselves from the band for a few months to give birth, primarily in the fall. It has to contest with other spider monkeys, wooly monkeys, and howler monkeys for food and territory.[6]

Food

The Peruvian spider monkey feeds on leaves, berries, small animals such as birds and frogs, flowers, termites, honey, grubs, and fruits. It is primarily frugivorous with a tendency to exhibit folivory in times of fruit scarcity.[4] It will also eat insects, baby birds, bird eggs, and frogs.[6] In the Amazon, groups of Peruvian spider monkeys show strong seasonal variations in habitat based on the availability of fleshy fruits.[10] The foraging habits of this species causes the monkeys to be a vital component of seed dispersal patterns for many tree species in Amazonia.[11]

Growth and Reproduction

The spider monkey has a reproductive period that can span throughout the year, though most offspring are born at the start of the Autumn season. It has a gestation period of about 140 days. The pregnant female leaves the group to have her baby and returns 2–4 months later. The newborn spider monkey is independent at about 10 months.[6]

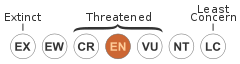

Conservation Status

This species of spider monkey, in addition to other species within the genus Ateles, is threatened due to exploitation by humans and habitat loss. It is currently listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as endangered and is listed in Appendix II of CITES despite having been listed as a species of "Least concern" in 2003.[2] Specialists with the IUCN claim that the species has declined by at least 50% over the past 45 years. This decline is partially due to the fact that these monkeys are targeted by hunters for sale and consumption in the Amazonian bushmeat trade. Furthermore, habitat in the southern part of its range is being developed for agriculture and habitat in the southwestern Peruvian region of Madre de Dios is being polluted and destroyed by illegal mining activity.[2] In Peru, illicit extraction of timber and wildlife products remain issues even in protected areas.[12] Studies show that in heavily-hunted and farmed areas, large-bodied primate species such as spider monkeys are likely to be some of the first species to be extirpated.[13][14] Reintroduction efforts by researchers at Reserva Ecologica Taricaya have begun along the lower Madre de Dios river where conservation efforts now provide a suitable release site and protected habitat.[14]

Similar or related species

In addition to external appearance, the Peruvian spider monkey differs from the red-faced spider monkey by the number of chromosomes (2n = 32 in the red-faced vs. 2n = 34 in the Peruvian) in addition to several specific chromosomal differences. The two species have been interbred in captivity, resulting in offspring with reduced fertility (but not sterility).[15] There are several related species such as the Central American spider monkey or Geoffroy's spider monkey (A. geoffroyi), and the brown spider monkey (A. hybridus) and the species' closest relative the white-bellied spider monkey (A. belzebuth). All of these have a prehensile tail, a thumbless hand, and other characteristics that are found in all spider monkeys.[16]

References

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 150. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wallace, R.B., Mittermeier, R.A., Cornejo, F. & Boubli, J.-P. (2008). "Ateles chamek". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 19 January 2012. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is endangered.

- ↑ Mittermeier, RA (1978). "Locomotion and Posture in Ateles geoffroyi and Ateles paniscus". Folia Primatologica 30 (3): 161–193. doi:10.1159/000155862.

- 1 2 Felton, Annika; Adam Felton; Jeff T. Wood; David B. Lindenmayer (2008). "Diet and Feeding Ecology of Ateles chamek in a Bolivian Semihumid Forest: The Importance of Ficus as a Staple Food Resource". International Journal of Primatology 29: 379–403. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9241-1.

- 1 2 Haugaasen, T., and Peres, C. Primate assemblage structure in Amazonian flooded and unflooded forests. American J of Primatology 67:243-258, 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Spider Monkeys, Great Book of the Animal Kingdom, Crescent Books, Inc., ISBN 0-517-08801-0 pp. 378-379

- ↑ Iwanaga, S., Ferrari S.F., 2002. Geographic distribution and abundance of woolly (Lagothrix cana) and spider (Ateles chamek) monkeys in southwestern Brazilian Amazonia. American Journal of Primotology.

- ↑ Wallace, Robert (2006). "Seasonal Variations in Black-Faced Black Spider Monkey (Ateles chamek) Habitat Use and Ranging Behavior in a Southern Amazonian Tropical Forest". American Journal of Primatology 68: 313–332. doi:10.1002/ajp.20227.

- ↑ Iwanaga, S., Ferrari S.F., 2001. Party Size and Diet of Syntopic Atelids (Ateles chamek and Lagothrix cana) in Southwestern Brazilian Amazonia.

- ↑ Wallace, R.B. Seasonal variations in black-faced spider monkey (Ateles chamek) habitat use and ranging behavior in a southern Amazonian tropical forest. American J of Primatology 68(4):313-332, 2006.

- ↑ Nunez-Iturri, Gabriela; Henry F. Howe (2007). "Bushmeat and the Fate of Trees with Seeds Dispersed by Large Primates in a Lowland Rain Forest in Western Amazonia". Biotropica 39 (3): 348–354. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00276.x.

- ↑ Vuohelainen, Anni Johanna; Lauren Coad; Toby R. Marthews; Yadvinder Malhi; Timothy J. Killeen (2012). "The Effectiveness of Contrasting Protected Areas in Preventing Deforestation in Madre de Dios, Peru". Environmental Management 50 (4): 645–663. doi:10.1007/s00267-012-9901-y.

- ↑ Naughton-Treves, Lisa; JOSE LUIS MENA,‡ ADRIAN TREVES,* NORA ALVAREZ,* AND VOLKER CHRISTIAN RADELOFF§ (2003). "Wildlife Survival Beyond Park Boundaries: the Impact of Slash-and-Burn Agriculture and Hunting on Mammals in Tambopata, Peru". Conservation Biology 17 (4): 1106–1117. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.02045.x. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 Bello, Raul. "Rehabilitation and Reintroduction Program of Ateles chamek in the southeastern Peruvian Amazon". Grupo de Primatología en Perú.

- ↑ de Boer, L.E.M., de Bruijn, M., 2005. Chromosomal distinction between the red-faced and black-faced black spider monkey (Ateles paniscus paniscus and A. chamek.)

- ↑ Spider Monkey, Animal The Definitive Visual Guide to the World’s Wildlife, ISBN 0-7894-7764-5 p. 123; Spider Monkeys, Great Book of the Animal Kingdom, Crescent Books, Inc., ISBN 0-517-08801-0 pp. 378-379

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||