Church of the East

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

|

Liturgy and worship |

|

The Church of the East (Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ʿĒ(d)tāʾ d-Maḏn(ə)ḥāʾ), also known as the Nestorian Church,[note 1] is a Christian church within the Syriac tradition of Eastern Christianity. It was the Christian church of the Sasanian Empire, and quickly spread widely through Asia. Between the 9th and 14th centuries it represented the world's largest Christian church in terms of geographical extent, with dioceses stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to China and India. Several modern churches claim continuity with the historical Church of the East.

The Church of the East was headed by the Patriarch of the East, continuing a line that, according to tradition, stretched back to the Apostolic Age. Liturgically, the church adhered to the East Syrian Rite, and theologically, it adopted the doctrine of Nestorianism, which emphasizes the distinctness of the divine and human natures of Jesus. This doctrine and its namesake, Nestorius (386–451), were condemned by the Council of Ephesus in 431, leading to the Nestorian Schism and a subsequent exodus of Nestorius' supporters to Sasanian Persia. The existing Christians in Persia welcomed these refugees and gradually adopted Nestorian doctrine by the 5th century, leading the Church of Persia to be known alternately as the Nestorian Church.

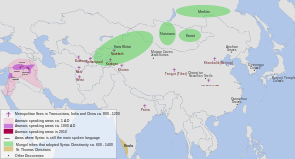

The church grew rapidly under the Sasanians, and following the Muslim conquest of Persia (633-654) it was designated as a protected dhimmi community under Muslim rule. From the 6th century it expanded greatly, establishing communities in India (the Saint Thomas Christians), among the Mongols in Central Asia, and in China, which became home to a thriving community under the Tang dynasty from the 7th to the 9th century. In the 13th and 14th centuries the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Nestorian Christians sat in the Mongol court.

From its peak of geographical extent, the church experienced a rapid period of decline starting in the 14th century, due in large part to outside influences. The Mongol Empire dissolved into civil war, the Chinese Ming dynasty overthrew the Mongols (1368) and ejected Christians and other foreign influences from China, and many Mongols in Central Asia converted to Islam. The Muslim Mongol leader Timur (1336–1405) nearly eradicated the remaining Christians in Persia; thereafter, Nestorian Christianity remained largely confined to Upper Mesopotamia and to the Malabar Coast of India. In the 16th century, the Church of the East underwent a schism from which three distinct churches eventually emerged: the modern Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East (which split from the former over reforms such as the use of the Gregorian Calendar), and the Chaldean Catholic Church, an Eastern Catholic Church in communion with the Holy See.

Organization and structure

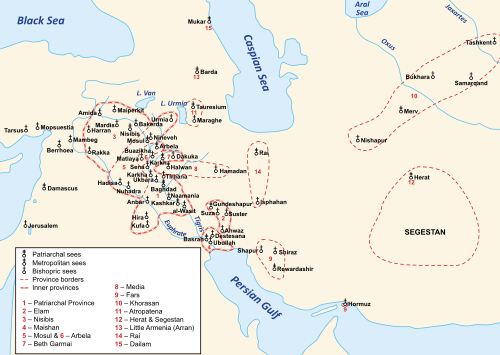

The Church of the East was headed by the Patriarch of the East, an office that traces its origin to the Apostolic Age. The head of the church also bears the title "Catholicos". Like the churches from which it developed, the Church of the East has an ordained clergy divided into the three traditional orders of deacon, priest (or presbyter), and bishop. Also like other churches, it has an episcopal polity: organization by dioceses, each headed by a bishop and made up of several individual parish communities overseen by priests. Dioceses are organized into provinces under the authority of a metropolitan bishop. The office of metropolitan bishop is an important one, and comes with additional duties and powers; canonically, only metropolitans can consecrate a patriarch.[1] The Patriarch also has the charge of the Province of the Patriarch.

For most of its history the church had six or so Interior Provinces in its heartland in northern Mesopotamia, southeastern Anatolia, and northwestern Iran and an increasing number of Exterior Provinces elsewhere. Most of these latter were located farther afield within the territory of the Sasanian Empire (and later the Caliphate), but very early on, provinces formed beyond the empire's borders as well. By the 10th century, the church had between 20[2] and 30 metropolitan provinces[3][4] including in China and India.[2] The Chinese provinces were lost in the 11th century, and in the subsequent centuries, other exterior provinces went into decline as well. However, in the 13th century, during the Mongol Empire, the church added two new metropolitan provinces in North China, Tangut and Katai and Ong.[3]

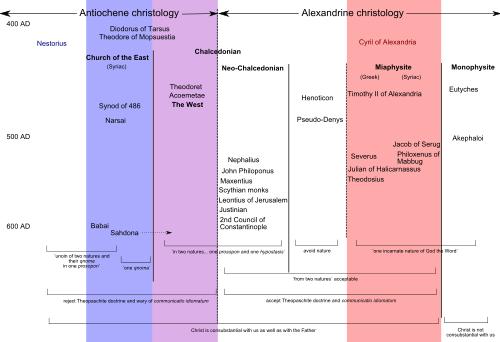

Nestorianism

The Church of the East became associated with Nestorianism, a Christological doctrine attributed to Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428 – 431 AD, which emphasizes the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus.[5]

Nestorius's doctrine represented the culmination of a philosophical current developed by scholars at the School of Antioch, most notably Nestorius's mentor Theodore of Mopsuestia. This became a source of controversy when Nestorius publicly challenged usage of the title Theotokos (literally, "Bearer of God") for the Virgin Mary.[6] He suggested that the title denied Christ's full humanity, arguing instead that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos and the human Jesus, and proposed Christotokos (literally, "Bearer of the Christ") as a more suitable alternative title. These statements drew criticism from other prominent churchmen, particularly from Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, leading to the First Council of Ephesus in 431, which condemned Nestorius for heresy and deposed him as patriarch.[7] Nestorianism was officially anathematized, a ruling reiterated at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. However, a number of churches, particularly those associated with the School of Edessa in Assyria and northern Mesopotamia, supported Nestorius—though not necessarily the doctrine ascribed to him—and broke with the churches of the Roman and Byzantine Empires. Many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to Sasanian Persia.[2][8] These events are known as the Nestorian Schism.

Although the "Nestorian" label was initially a theological one, applied to followers of the Nestorian doctrine, it was soon applied to all associated East Syrian Rite churches with little regard for theological consideration. While often used disparagingly in the West to emphasize the Church of the East's connections to a heretical doctrine, many writers of the Middle Ages and since have simply used the label descriptively, as a neutral and conventional term for the church.[3] Other names for the church include "Persian Church", "Syriac" or "Syrian" (often distinguished as East Syriac/Syrian),[3] and "Assyrian".[3]

In modern times some scholars have sought to avoid the Nestorian label, preferring "Church of the East" or one of the other alternatives. This is due both to the term's derogatory connotations, and because it implies a stronger connection to Nestorian doctrine than may have historically existed. As Wilhelm Baum and Dietmar W. Winkler said, "Nestorius himself was no Nestorian" in terms of doctrine.[9] Even from the beginning, not all churches called "Nestorian" adhered to the Nestorian doctrine; in China, it has been noted that none of the various sources for the local Nestorian church refer to Christ as having two natures. As such, in 2006 an academic conference changed its name from "Research on Nestorianism in China", explaining in the Preface, "...it was decided not to keep the term "Nestorianism" in the title of the future conferences and the present book, but to use the term Church of the East, which is correct and wide enough to cover the whole field of the research."[10]

The 2000 work, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913, offers an explanation in the first chapter:

The terminology used in this study deserves a word of explanation. Until recently the Church of the East was usually called the 'Nestorian' church, and East Syrian Christians were either 'Nestorians' or (after the schism of 1552) by the ethnic and geographic misnomer 'Chaldeans'. During the period covered in this study, the word 'Nestorian' was used both as a term of abuse by those who disapproved of the traditional East Syrian theology, as a term of pride by many of its defenders (including Abdisho of Nisibis in 1318, the Mosul patriarch Eliya X Yohannan Marogin in 1672, and the Qudshanis patriarch Shem'on XVII Abraham in 1842), and as a neutral and convenient descriptive term by others. Nowadays it is generally felt that the term carries a stigma, and students of the Church of the East are advised to avoid its use. In this thesis the theologically neutral adjective 'East Syrian' has been used wherever possible, and the term 'traditionalist' to distinguish the non-Catholic branch of the Church of the East after the schism of 1552. The modern term 'Assyrian', often used in the same sense, was unknown for most of the period covered in this study, and has been avoided.[3]

The church was formed in Parthian- and Sasanian-ruled Assyria (Athura/Assuristan) and many of its original members in Upper Mesopotamia and south eastern Anatolia had since ancient times been described by both themselves and neighbouring peoples as Assyrians,[11][12] however the church itself did not specifically use the prefix Assyrian until later times.

The Assyrian Church of the East has shunned the "Nestorian" label in recent times. The church's former head, Catholicos-Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV, explicitly rejected the term on the occasion of his consecration in 1976.[13]

Scriptures

The Peshitta, in some cases lightly revised and with missing books added, is the standard Syriac Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition: the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syrian Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Maronites, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

The Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated from Hebrew, although the date and circumstances of this are not entirely clear. The translators may have been Syriac-speaking Jews or early Jewish converts to Christianity. The translation could have been done separately for different texts, and the whole work was probably done by the second century.

The New Testament of the Peshitta, which originally excluded certain disputed books (Second Epistle of Peter, Second Epistle of John, Third Epistle of John, Epistle of Jude, Book of Revelation), had become the standard by the early 5th century.

Early history

Parthian and Sasanian periods

Christians were already forming communities in Assyria (Athura) as early as the first century, when it was part of the Parthian Empire. By the third century, the area had been conquered by the Persian Sasanian Empire (becoming the province of Assuristan), and there were significant Christian communities in northern Mesopotamia, Elam, and Fars.[14] The Church of the East traced its origins ultimately to the evangelical activity of the apostles Addai, Mari and Thomas, but leadership and structure was disorganized until the establishment of the diocese of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the bishop of which came to be recognized as Catholicos, or universal leader, of the church. This position received an additional title later, Patriarch of the East.[15]

These early Christian communities in Assyria, Elam and Fars were reinforced in the fourth and fifth centuries by large-scale deportations of Christians from the eastern Roman Empire.[16] However, the Persian Church faced several severe persecutions, notably during the reign of Shapur II (339–79), from the ethnically Persian Zoroastrian majority who accused it of Roman leanings.[17] The church grew considerably during the Sasanian period, but the pressure of persecution led to the Persian Church declaring itself independent of all other Christian churches in 424.[2]

Meanwhile, in the Roman Empire, the Nestorian Schism had led many of Nestorius' supporters to relocate to the Persian Empire. The Persian Church increasingly aligned itself with the Nestorian schismatics, a measure encouraged by the Zoroastrian ruling class. The church became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine over the next decades, furthering the divide between Roman and Nestorian Christianity. In 486 the Metropolitan of Nisibis, Barsauma, publicly accepted Nestorius' mentor, Theodore of Mopsuestia, as a spiritual authority. In 489, when the School of Edessa in Mesopotamia was closed by Byzantine Emperor Zeno for its Nestorian teachings, the school relocated to its original home of Nisibis, becoming again the School of Nisibis, leading to a wave of Nestorian immigration into the Persian Empire. The Church of the East patriarch Mar Babai I (497–502) reiterated and expanded upon his predecessors' esteem for Theodore, solidifying the church's adoption of Nestorianism.[2]

Now firmly established in the Persian Empire, with centers in Nisibis, Ctesiphon, and Gundeshapur, and several metropolitan sees, the Church of the East began to branch out beyond the Persian Sasanian Empire. However, through the 6th century the church was frequently beset with internal strife and persecution from the Zoroastrians. The infighting led to a schism, which lasted from 521 until around 539, when the issues were resolved. However, immediately afterward Roman-Persian conflict led to a renewed persecution of the church by the Sasanid King Khosrau I; this ended in 545. The church survived these trials under the guidance of Patriarch Mar Abba I, who had converted to Christianity from Zoroastrianism.[2]

By the end of the 5th century and the middle of the 6th, the area occupied by Nestorians included "all the countries to the east and those immediately to the west of the Euphrates", including Persia, Egypt, Syria, Arabia, Socotra, Mesopotamia (Assyria and Babylonia), Media, Bactria, Hyrcania, and India; and possibly also to places called Calliana, Male, and Sielediva (Ceylon).[18] Beneath the Patriarch in the hierarchy were nine metropolitans, and clergy were recorded among the Huns, in Persarmenia, Media, and the island of Dioscoris in the Indian Ocean.[18]

Nestorian Christianity also flourished in the kingdom of the Lakhmids until the Islamic conquest, particularly after the ruler Al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir officially converted in c. 592.

Islamic rule

After the Sasanian Empire was conquered by Muslim Arabs in 644, the newly established Rashidun Caliphate designated the Church of the East as an official dhimmi minority group headed by the Patriarch of the East. As with all other Christian and Jewish groups given the same status, the Church was restricted within the Caliphate, but also given a degree of protection. Nestorians were not permitted to proselytize or attempt to convert Muslims, but their missionaries were otherwise given a free hand, and they increased missionary efforts farther afield. Missionaries established dioceses in India (the Saint Thomas Christians). They made some advances in Egypt, despite the strong Monophysite presence there, and they entered Central Asia, where they had significant success converting local Tartar tribes. Nestorian missionaries were firmly established in China during the early part of the Tang Dynasty (618–907); the Chinese source known as the Nestorian Stele describes a mission under a proselyte named Alopen as introducing Nestorian Christianity to China in 635. In the 7th century, the Church had grown to have two Nestorian archbishops, and over 20 bishops east of the Iranian border of the Oxus River.[19]

The patriarch Timothy I (780–823), a contemporary of the caliph Harun al-Rashid, took a particularly keen interest in the missionary expansion of the Church of the East. He is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, for Armenia, for Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, for Rai in Tabaristan, for Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, for China, and possibly also for Tibet. He also detached India from the metropolitan province of Fars and made it a separate metropolitan province, known as India.[20] By the 10th century the Church of the East had a number of dioceses stretching from across the Caliphate's territories to India and China.[2]

Nestorian Christians made substantial contributions to the Islamic Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, particularly in translating the works of the ancient Greek philosophers to Syriac and Arabic.[21] Nestorians made their own contributions to philosophy, science (such as Hunayn ibn Ishaq, Qusta ibn Luqa, Masawaiyh, Patriarch Eutychius, Jabril ibn Bukhtishu) and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub). The personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Assyrian Christians such as the long serving Bukhtishu dynasty.[22][23]

Expansion

The Church of the East had a vigorous corps of missionaries, who proceeded eastward from their base in Persia, having particular success in India, among the Mongols, and reaching as far as China and Korea.

India

The Saint Thomas Christian community of Kerala, India, who trace their origins to the evangelism of Thomas the Apostle, had a long connection with the Church of the East. The earliest known organized Christian presence in Kerala dates to the 3rd century, when Nestorian Christian settlers and missionaries from Persia settled in the region.[24] The Saint Thomas Christians traditionally credit the mission of Thomas of Cana, a Nestorian from the Middle East, with the further expansion of their community.[25] From at least the early 4th century, the Patriarch of the Church of the East provided the Saint Thomas Christians with clergy, holy texts, and ecclesiastical infrastructure, and around 650 Patriarch Ishoyahb III solidified the church's jurisdiction in India.[26] In the 8th century Patriarch Timothy I organised the community as the Ecclesiastical Province of India, one of the church's Provinces of the Exterior. After this point the Province of India was headed by a metropolitan bishop, provided from Persia, who oversaw a varying number of bishops as well as a native Archdeacon, who had authority over the clergy and also wielded a great amount of secular power. The metropolitan see was probably in Cranganore, or (perhaps nominally) in Mylapore, where the shrine of Thomas was located.[25]

In the 12th century Indian Nestorianism engaged the Western imagination in the figure of Prester John, supposedly a Nestorian ruler of India who held the offices of both king and priest. The geographically remote Malabar church survived the decay of the Nestorian hierarchy elsewhere, enduring until the 16th century when the Portuguese arrived in India. The Portuguese at first accepted the Nestorian sect, but by the end of the century they had determined to actively bring the Saint Thomas Christians into full communion with Rome under the Latin Rite. They installed Portuguese bishops over the local sees and made liturgical changes to accord with the Latin practice. In 1599 the Synod of Diamper, overseen by Aleixo de Menezes, Archbishop of Goa, led to a revolt among the Saint Thomas Christians; the majority of them broke with the Catholic Church and vowed never to submit to the Portuguese in the Coonan Cross Oath of 1653. In 1661 Pope Alexander VII responded by sending a delegation of Carmelites headed by Chaldean Catholics to re-establish the East Syrian rites under an Eastern Catholic hierarchy; by the next year, 84 of the 116 communities returned, forming the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. The rest, which became known as the Malankara Church, soon entered into communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church; from the Malankara Church has also come the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church.

China

Christianity reached China by 635, and its relics can still be seen in Chinese cities such as Xi'an. The Nestorian Stele, set up on 7 January 781 at the then-capital of Chang'an, attributes the introduction of Christianity to a mission under a Persian cleric named Alopen in 635, in the reign of Emperor Taizong of Tang during the Tang Dynasty.[27][28] The inscription on the Nestorian Stele, whose dating formula mentions the patriarch Hnanishoʿ II (773–80), gives the names of several prominent Christians in China, including the metropolitan Adam, the bishop Yohannan, the 'country-bishops' Yazdbuzid and Sargis and the archdeacons Gigoi of Khumdan (Chang'an) and Gabriel of Sarag (Loyang). The names of around seventy monks are also listed.[29]

Nestorian Christianity thrived in China for approximately 200 years, but then faced persecution from Emperor Wuzong of Tang (reigned 840–846). He suppressed all foreign religions, including Buddhism and Christianity, causing it to decline sharply in China. A Syrian monk visiting China a few decades later described many churches in ruin. The Church disappeared from China in the early 10th century, coinciding with the collapse of the Tang Dynasty and the tumult of the next years (the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period).[30]

Christianity in China experienced a significant revival during the Mongol-created Yuan Dynasty, established after the Mongols had conquered China in the 13th century. Marco Polo in the 13th century and other medieval Western writers described many Nestorian communities remaining in China and Mongolia; however, they clearly were not as vibrant as they had been during Tang times.

Mongolia and Central Asia

The Church of the East enjoyed a final period of expansion under the Mongols. Several Mongol tribes had already been converted by Nestorian missionaries in the 7th century, and Christianity was therefore a major influence in the Mongol Empire.[31] Genghis Khan was a shamanist, but his sons took Christian wives from the powerful Kerait clan, as did their sons in turn. During the rule of Genghis's grandson, the Great Khan Mongke, Nestorian Christianity was the primary religious influence in the Empire, and this also carried over to Mongol-conquered China, during the Yuan Dynasty. It was at this point, in the late 13th century, that the Church of the East reached its greatest geographical extent. But Mongol power was already waning, as the Empire dissolved into civil war, and it reached a turning point in 1295, when Ghazan, the Mongol ruler of the Ilkhanate, made a formal conversion to Islam when he took the throne.

Jerusalem and Cyprus

Rabban Bar Sauma had initially conceived of his journey to the West as a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, so it is possible that there was a Nestorian presence in the city ca.1300. There was certainly a recognizable Nestorian presence at the Holy Sepulchre from the 1348 through 1575, as contemporary Franciscan accounts indicate.[32] At Famagusta, Cyprus, a Nestorian community was established just before 1300, and a church was built for them ca.1339.[33]

Schism and later history

Collapse of the exterior provinces

The 'exterior provinces' of the Church of the East, with the important exception of India, collapsed during the second half of the fourteenth century. Although little is known of the circumstances of the demise of the Nestorian dioceses in Central Asia (which may never have fully recovered from the destruction caused by the Mongols a century earlier), it was probably due to a combination of persecution, disease, and isolation.

The blame for the destruction of the Nestorian communities east of northern Iraq has often been thrown upon the Turco-Mongol leader Tamerlane, whose campaigns during the 1390s spread havoc throughout Persia and Central Asia, but in many parts of Central Asia, Christianity had died out decades before Tamerlane's campaigns. The surviving evidence from Central Asia, including a large number of dated graves, indicates that the crisis for the Church of the East occurred in the 1340s rather than the 1390s. Several contemporary observers, including the papal envoy Giovanni de' Marignolli, mention the murder of a Latin bishop in 1339 or 1340 by a Muslim mob in Almaliq, the chief city of Tangut, and the forcible conversion of the city's Christians to Islam.

At the end of the 19th century, tombstones in two East Syrian cemeteries were discovered and dated in Mongolia. They dated from 1342, and several commemorated deaths during a Black Death in 1338. In China, the last references to Nestorian and Latin Christians date from the 1350s. It is likely that all foreign Christians were expelled from China soon after the revolution of 1368, which replaced the Mongol Yuan dynasty with the xenophobic Ming dynasty.

By the 15th century, Nestorian Christianity was largely confined to the Eastern Aramaic speaking Assyrian communities of northern Mesopotamia, in and around the rough triangle formed by Mosul and Lakes Van and Urmia, the same general region where the Church of the East had first emerged between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD.[34] Small Nestorian communities were located further west, notably in Jerusalem and Cyprus, but the Malabar Christians of India represented the only significant survival of the once-thriving exterior provinces of the Church of the East.[35]

Schism of 1552

Around the middle of the fifteenth century the patriarch Shemʿon IV Basidi made the patriarchal succession hereditary, normally from uncle to nephew. This practice, which resulted in a shortage of eligible heirs, eventually led to a schism in the Church of the East.[36] The patriarch Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–58) caused great offense at the beginning of his reign by designating his twelve-year-old nephew Khnanishoʿ as his successor, presumably because no older relatives were available.[37] Several years later, probably because Khnanishoʿ had died in the interim, he designated as successor his fifteen-year-old brother Eliya, the future patriarch Eliya VII (1558–91).[38] These appointments, combined with other accusations of impropriety, caused discontent throughout the church, and by 1552 Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb had become so unpopular that a group of bishops, principally from the Amid, Sirt and Salmas districts in northern Mesopotamia, chose a new patriarch, electing a monk named Yohannan Sulaqa, the superior of Rabban Hormizd Monastery near the Assyrian town of Alqosh.[39] However, no bishop of metropolitan rank was available to consecrate him, as canonically required. Franciscan missionaries were already at work among the Nestorians, and they persuaded Sulaqa's supporters to legitimize their position by seeking their candidate's consecration by Pope Julius III (1550–5).[40]

Sulaqa went to Rome to put his case in person. At Rome he made a satisfactory Catholic profession of faith and presented a letter, drafted by his supporters in Mosul, which set out his claims to be recognized as patriarch. On April 9, having satisfied the Vatican that he was a good Catholic, Sulaqa was consecrated bishop and archbishop in the basilica of Saint Peter. On April 28 he was recognized as "patriarch of Athura and Mosul" by pope Julius III in the bull Divina disponente clementia and received the pallium from the pope's hands at a secret consistory in the Vatican. These events, which marked the birth of the Chaldean Catholic Church, created a permanent schism in the Church of the East.[40]

Sulaqa was consecrated "patriarch of Athura and Mosul" in Rome in April 1553 and returned to northern Mesopotamia towards the end of the same year.[39] In December 1553 he obtained documents from the Ottoman authorities recognizing him as an independent "Chaldean" patriarch, and in 1554, during a stay of five months in Amid, consecrated five metropolitan bishops (for the dioceses of Gazarta, Hesna d'Kifa, Amid, Mardin and Seert). Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb responded by consecrating two more underage members of the patriarchal family as metropolitans for Nisibis and Gazarta. He also won over the governor of ʿAmadiya, who invited Sulaqa to ʿAmadiya, imprisoned him for four months, and put him to death in January 1555.[39]

Sees in Qochanis, Amid, and Alqosh

The connections with Rome loosened up under Shimun VIII Sulaqa's successors, who all used the patriarchal name Shimun. The last patriarch to be formally recognized by the Pope died in the 1600, and the heredity of the office was reintroduced, and thus by 1660 the Church of the East had become divided into two patriarchates, the Eliya line in Alqosh (which comprised those who had not entered into Communion with Rome) and the Shimun line. In 1672 the Patriarch of the Shimun line, Mar Shimun XIII Denha, moved his seat to the Assyrian village of Qochanis in the mountains of Hakkari.[41] In 1692 he formally broke communion with Rome and he allegedly resumed relations with the line at Alqosh.

In the Western regions, a new start for the so-called Chaldean Patriarchate began in 1672 when Mar Joseph I, then the metropolitan of Amid, entered in communion with Rome, separating from the Patriarchal see of Alqosh. In 1681 the Holy See granted him the title of "Patriarch of the Chaldeans deprived of its patriarch" as leader of the Assyrian people who stayed in communion with Rome, and thus forming the third patriarchate of the Church of the East.

Josephite line of Amid

All Joseph I's successors took the name of Joseph. The life of this patriarchate was difficult: the leadership was continually vexed by traditionalists, while the community struggled under the tax burden imposed by the Ottoman authorities. Nevertheless, its influence expanded from the original towns of Amid and Mardin toward the area of Mosul, where they relocated the see.

Yohannan Hormizd, the last in the Eliya hereditary line in Alqosh, made a Catholic profession of faith in 1780. He entered full communion with the Roman see in 1804, but he was recognized as Patriarch by the Pope only in 1830. This merged the majority of the Patriarchate of Alqosh with the Josephite line of Amid, thus forming the modern Chaldean Catholic Church.

The Shimun line of patriarchs at Qochanis, which extended mainly in the Northern mountains, remained independent of the Chaldean Church, and the patriarchate of the present-day Assyrian Church of the East, now located in Chicago, Illinois, forms the continuation of this line.[41]

20th century

The Assyrian Church of the East faced a further split in 1898, when a bishop and a number of followers from the Urmia area in Iran entered communion with the Russian Orthodox Church, and again in 1964 when some traditionalists responded to ecclesiastical reforms brought on by Patriarch Mar Eshai Shimun XXIII (1908–1975) by forming the independent Ancient Church of the East.

Today the Assyrian Church has about 170,000 members, mostly living in Iran, Iraq, and Syria.[2] The Patriarchate of the Assyrian Church of the East is in exile in Chicago, and that of the Ancient Church of the East is in Baghdad.

In the Common Christological Declaration between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East in 1994, the two churches recognized the legitimacy and rightness of each other's titles for Mary.[42]

In 2015, Chaldean Catholic Patriarch Louis Raphael I Sako proposed unifying the three modern Patriarchates into a re-established Church of the East.[43]

See also

- Constantinople II

- Schism of the Three Chapters

- Ancient Church of the East

- Syriac Orthodox Church

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Dioceses of the Church of the East to 1318

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1318–1552

- Dioceses of the Church of the East, 1552–1913

- List of Patriarchs of the Church of the East

- Syriac Christianity

Notes

- ↑ Though the "Nestorian" label is well established, it has been contentious. See the Nestorianism section for the naming issue and alternate designations for the church.

References

Citations

- ↑ Wilmshurst, Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 21–2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Nestorian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wilmshurst, p. 4

- ↑ According to John Foster, Church of the Tang Dynasty, p. 34, in the 9th century there were 25 metropolitans

- ↑ Silverberg, Robert (1972). The Realm of Prester John. Doubleday. pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Foltz, p. 63

- ↑ "Cyril of Alexandria, Third epistle to Nestorius, including the twelve anathemas". Monachos.net.

- ↑ "Nestorius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ↑ Baum, W. & Winkler, D., (2000, 2003[tr.]) The Church of the East, London, RoutledgeCurzon, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Hofrichter, Peter L. (2006). "Preface". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter (editors). Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, VII.63, s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

- ↑ Frye, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms, pp. 30

- ↑ Hill, p. 107

- ↑ Winkler, Church of the East: a concise history, p. 1

- ↑ Roberson, Ronald (1999) [1986]. The Eastern Christian Churches: a brief survey. Edizioni Orientalia Christiana. ISBN 8872103215.

- ↑ Culture and customs of Iran, p. 61

- ↑ Foster, pp. 26–27

- 1 2 Stewart, pp. 13−14

- ↑ Foster, p. 33

- ↑ Fiey, POCN, 47 (Armenia), 72 (Damascus), 74 (Dailam and Gilan), 94–6 (India), 105 (China), 124 (Rai), 128–9 (Sarbaz), 128 (Samarqand and Beth Turkaye) and 139 (Tibet)

- ↑ Hill, Donald. Islamic Science and Engineering. 1993. Edinburgh Univ. Press. ISBN 0-7486-0455-3, p. 4

- ↑ Rémi Brague, Assyrians contributions to the Islamic civilization

- ↑ Britannica, Nestorian

- ↑ Frykenberg, Eric (2008). Christianity in India: from Beginnings to the Present, pp. 102–107; 115. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-826377-5.

- 1 2 Baum, Wilhelm; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 0-415-29770-2.

- ↑ Baum, Wilhelm; Dietmar W. Winkler (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 0-415-29770-2.

- ↑ Ding, Wang (2006). "Renmants of Christianity from Chinese Central Asia in Medieval ages". In Malek, Roman; Hofrichter, Peter (editors). Jingjiao: the Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Steyler Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8050-0534-0.

- ↑ Stewart, p. 169

- ↑ Stewart, p. 183

- ↑ Moffett, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 97

- ↑ H. C. Luke, "The Christian Communities in the Holy Sepulchre," in Jerusalem 1920–1922 (London: John Murray, 1924), pp. 46–56.

- ↑ J. M. Fiey, Pour un Oriens Christianus novus; répertoire des diocèses Syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. (Beirut, 1993) p. 71. David Wilsmhurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913 (Louvain: Peeters, 2000), p. 66.

- ↑ Frazee, p. 55.

- ↑ Wilmshurst, Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913, 345–7

- ↑ Wilmshurst, p. 19

- ↑ Wilsmhurst, p. 21.

- ↑ Wilmshurst, pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 3 Wilmshurst, p. 22.

- 1 2 Habbi, "Signification de l'union chaldéenne de Mar Sulaqa avec Rome en 1553", L'Orient Syrien 11 (1966), 99–132 and 199–230; Wilmshurst, Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, pp. 21–22

- 1 2 Heleen H.L. Murre. "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ↑ "Common Christological declaration between the Catholic church and the Assyrian Church of the East". The Holy See. November 11, 1994. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Valente, Gianni (25 June 2015). "Chaldean Patriarch gambles on re-establishing "Church of the East"". Vatican Insider.

Bibliography

- Angold, Michael, ed. (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity. Volume 5, Eastern Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W (1 January 2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History, London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29770-2. Google Print, retrieved 16 July 2005.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2006). Culture and customs of Iran. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32053-8.

- "Nestorius and Nestorianism". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Fiey, J. M., Pour un Oriens Christianus novus; répertoire des diocèses Syriaques orientaux et occidentaux (Beirut, 1993)

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition, 2010 ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. Great Britain: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Charles A. Frazee, Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923, Cambridge University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-521-02700-4

- Gumilev, Lev N. (2003). Poiski vymyshlennogo tsarstva [Looking for the mythical kingdom] (in Russian). Moscow: Onyx Publishers. ISBN 5-9503-0041-6.

- Hill, Henry, ed (1988). Light from the East: A Symposium on the Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian Churches. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221–1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Jenkins, Philip. The Lost History of Christianity. HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-147281-6.

- Moffett, Samuel Hugh (1999). "Alopen". Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions: 14–15.

- Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3539-9.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1650-6.

- Seleznyov, Nikolai N., "Nestorius of Constantinople: Condemnation, Suppression, Veneration, With special reference to the role of his name in East-Syriac Christianity" in: Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 62:3–4 (2010): 165–190.

- Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian missionary enterprise, the story of a church on fire. Edinburgh, T. & T. Clark.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0876-5.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||