Ring of periods

In mathematics, a period is a number that can be expressed as an integral of an algebraic function over an algebraic domain. Sums and products of periods remain periods, so the periods form a ring.

Maxim Kontsevich and Don Zagier (2001) gave a survey of periods and introduced some conjectures about them.

Definition

A real number is called a period if it is the difference of volumes of regions of Euclidean space given by polynomial inequalities with rational coefficients. More generally a complex number is called a period if its real and imaginary parts are periods.

The values of absolutely convergent integrals of rational functions with algebraic coefficients, over domains in  given by polynomial inequalities with algebraic coefficients are also periods, since integrals and irrational algebraic numbers are expressible in terms of areas of suitable domains.

given by polynomial inequalities with algebraic coefficients are also periods, since integrals and irrational algebraic numbers are expressible in terms of areas of suitable domains.

Examples

Besides the algebraic numbers, the following numbers are known to be periods:

- The natural logarithm of any algebraic number

- π

- Elliptic integrals with rational arguments

- All zeta constants (the Riemann zeta function of an integer) and multiple zeta values

- Special values of hypergeometric functions at algebraic arguments

- Γ(p/q)q for natural numbers p and q.

An example of real number that is not a period is given by Chaitin's constant Ω. Currently there are no natural examples of computable numbers that have been proved not to be periods, though it is easy to construct artificial examples using Cantor's diagonal argument. Plausible candidates for numbers that are not periods include e, 1/π, and Euler–Mascheroni constant γ.

Purpose of the classification

The periods are intended to bridge the gap between the algebraic numbers and the transcendental numbers. The class of algebraic numbers is too narrow to include many common mathematical constants, while the set of transcendental numbers is not countable, and its members are not generally computable. The set of all periods is countable, and all periods are computable, and in particular definable.

Conjectures

Many of the constants known to be periods are also given by integrals of transcendental functions. Kontsevich and Zagier note that there "seems to be no universal rule explaining why certain infinite sums or integrals of transcendental functions are periods".

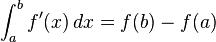

Kontsevich and Zagier conjectured that, if a period is given by two different integrals, then each integral can be transformed into the other using only the linearity of integrals, changes of variables, and the Newton–Leibniz formula

(or, more generally, the Stokes formula).

A useful property of algebraic numbers is that equality between two algebraic expressions can be determined algorithmically. The corresponding problem for periods is open, but the conjecture of Kontsevich and Zagier would at least imply that equality of periods is recursively enumerable: an algorithm which takes two integrals and tries all possible ways to transform one of them into the other one will eventually terminate if the integrals are equal (assuming the conjecture).

It is not expected that Euler's number e and Euler–Mascheroni constant γ are periods. The periods can be extended to exponential periods by permitting the product of an algebraic function and the exponential function of an algebraic function as an integrand. This extension includes all algebraic powers of e, the gamma function of rational arguments, and values of Bessel functions. If, further, Euler's constant is added as a new period, then according to Kontsevich and Zagier "all classical constants are periods in the appropriate sense".

References

- Belkale, Prakash; Brosnan, Patrick (2003), "Periods and Igusa local zeta functions", International Mathematics Research Notices (49): 2655–2670, doi:10.1155/S107379280313142X, ISSN 1073-7928, MR 2012522

- Kontsevich, Maxim; Zagier, Don (2001), "Periods", in Engquist, Björn; Schmid, Wilfried, Mathematics unlimited—2001 and beyond (PDF), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 771–808, ISBN 978-3-540-66913-5, MR 1852188

- Waldschmidt, Michel (2006), "Transcendence of periods: the state of the art" (PDF), Pure and Applied Mathematics Quarterly 2 (2): 435–463, doi:10.4310/PAMQ.2006.v2.n2.a3, ISSN 1558-8599, MR 2251476

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||