People's Republic of Bulgaria

| People's Republic of Bulgaria | ||||||

| Народна република България (Bulgarian) Narodna republika Balgariya (transliteration) | ||||||

| Satellite state of the Soviet Union[1] Member of the Warsaw Pact | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

| Anthem Our Republic, Hail! (until 1950)

Републико наша, здравей! (Bulgarian) Republiko nasha, zdravey! (transliteration) Dear Bulgaria, Land of Heroes (1950–1964) Българийо мила, земя на герои (Bulgarian) Balgariyo mila, zemya na geroi (transliteration) Dear Motherland (from 1964) | ||||||

Location of Bulgaria in Europe in 1990. | ||||||

| Capital | Sofia | |||||

| Languages | Bulgarian | |||||

| Government | Marxist–Leninist one-party state | |||||

| General Secretary | ||||||

| • | 1946–1949 | Georgi Dimitrov | ||||

| • | 1949–1954 | Valko Chervenkov | ||||

| • | 1954–1989 | Todor Zhivkov | ||||

| • | 1989–1990 | Petar Mladenov | ||||

| President | ||||||

| • | 1946–1947 (first) | Vasil Kolarov | ||||

| • | 1989–1990 (last) | Petar Mladenov | ||||

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | ||||||

| • | 1946–1949 (first) | Georgi Dimitrov | ||||

| • | 1990 (last) | Andrey Lukanov | ||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | |||||

| Historical era | Cold War | |||||

| • | Established | September 15, 1946 | ||||

| • | Disestablished | November 15, 1990 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | 1946 | 110,994 km² (42,855 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 1946 est. | 7,029,349 | ||||

| Density | 63.3 /km² (164 /sq mi) | |||||

| • | 1989 est. | 9,009,018 | ||||

| Density | 81.2 /km² (210.2 /sq mi) | |||||

| Currency | Bulgarian lev | |||||

| Internet TLD | .bg | |||||

| Calling code | +359 | |||||

The People's Republic of Bulgaria (PRB; Bulgarian: Народна република България (НРБ) Narodna republika Balgariya (NRB)) was the official name of the Bulgarian socialist republic that existed from 1946 to 1990, when the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP) ruled together with its coalition partner, the National Agrarian Party. Bulgaria was an Eastern Bloc country, part of Comecon, a member of the Warsaw Pact, and allied with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Founded from the anti-fascist resistance movements during World War II, the kingdom's administration was deposed in the coup of 1944 which ended the country's association with the Axis and led to the People's Republic being established in 1946. From the start, the BCP modeled its policies after those pioneered in the Soviet Union, transforming the country from an agrarian peasant society into an industrialized socialist society over the course of a decade. In the mid 1950s, after the death of Joseph Stalin, the conservative hardliners lost influence and a period of social liberalization and stability followed with varying degrees of conservative or liberal influence over time thereafter. After a new energy and transportation infrastructure was constructed, by 1960 manufacturing became the dominant sector of the economy and Bulgaria became a major exporter of household goods and, later on, computer technologies, earning it the nickname of "Silicon Valley of the Eastern Bloc." The country's relatively high productivity levels and high scores on social development rankings made it a model for other socialist countries' administrative policies.

In 1989, after a few years of liberal influence, political reforms were initiated and Todor Zhivkov, who had served as head of the party since 1954, was removed from office in a BCP congress. In 1990, under the new leadership of Georgi Parvanov, the BCP changed its name to the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) and adopted a centre-left political ideology in place of Marxism-Leninism. Following the BSP victory in the 1990 election, which was the first openly contested multi-party election since 1931, the name of the state was changed to the Republic of Bulgaria.

History

Early years and Chervenkov era

In 1944, with the oncoming of the Red Army through Romania, the Kingdom of Bulgaria changed its alliance and declared neutrality. On 5 September, the USSR declared war on the kingdom and three days later the Red Army entered north eastern Bulgaria, prompting the government to declare support in order to minimize military conflict. On 9 September, the communist partisans launched a coup d'état which de facto ended the rule of the monarchy and its administration, after which a new government assumed power led by the Fatherland Front (FF), which in itself was led by the Bulgarian Communist Party.

The new government began to severely crack down on Nazi collaborators. As the war drew to a close, the government expanded its campaign of political revolution to go after economic elites in banking and private business. This only intensified when it became apparent that the United States and United Kingdom had largely disinterested themselves in Bulgaria, and further intensified in November 1945, when Communist Party leader Georgi Dimitrov returned to Bulgaria after 22 years in exile. He made a truculent speech that made it apparent the party had no intentions of working with opposition groups who were against their revolution. Elections held a few weeks later resulted in a large majority for the Fatherland Front.

In September 1946, a referendum on whether to retain the monarchy or make Bulgaria a republic resulted in 95.6 percent voting in favour of a republic. Almost immediately after that Bulgaria was declared a people's republic. The young Tsar Simeon II, his mother and sister were required to leave the country. Vasil Kolarov, the number-three man in the party, became acting head of state.

Over the next year, the Communists consolidated their hold on power. Elections for a constituent assembly in October 1946 gave the Communists a majority. A month later, Dimitrov became prime minister. In December 1947, the constituent assembly ratified a new constitution for the republic, referred to as the "Dimitrov Constitution". The constitution was drafted with the help of Soviet jurists using the 1936 Soviet Constitution as a model. By 1948, the remaining opposition parties were either realigned or dissolved; the Social Democrats merged with the Communists, while the Agrarian Union became a loyal partner with the Communists.

During 1948-49, Orthodox, Muslim, Protestant and Roman Catholic religious organizations were restrained or banned. The Orthodox Church of Bulgaria continued functioning but never regained the influence it held under the monarchy; many high roles within the church would be assumed by communist functionaries.[2]

Dimitrov died in 1949. For a time, Bulgaria adopted collective leadership with Vulko Chervenkov becoming leader of the Communist Party and Vasil Kolarov becoming prime minister. This broke down a year later, when Kolarov died and Chervenkov assumed both roles of party leader and prime minister. Chervenkov started a process of rapid industrialization modeled after the Soviet industrialization led by Stalin in the 1930s. Like in the 1930s USSR, agriculture was collectivized by mandate and refusal to comply was punishable by imprisonment. Labor camps were set up and at the height of the campaign housed about 100,000 people. Thousands of people charged with treason or participating in counter-revolutionary conspiracy were sentenced to either death or life in prison.[3][4][5]

Yet, Chervenkov's support base even in the Communist Party was too narrow for him to survive long once his patron, Stalin, was gone. In March 1954, a year after Stalin's death, Chervenkov was deposed as Party Secretary with the approval of the new leadership in Moscow and replaced by the youthful Todor Zhivkov. Chervenkov stayed on as Prime Minister until April 1956, when he was finally dismissed and replaced by Anton Yugov.

Zhivkov era

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

|

Dissent and opposition 1953 uprisings

1956 protests

|

.jpg)

Zhivkov became the new leader of the BCP, which he remained for the next 33 years. The BCP retained its alliance with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), which was now led by Nikita Khrushchev who formally denounced Stalin at the CPSU congress in 1956. With conservative hardliners pushed aside, this brought in a period of liberal influence and reform. Relations were restored with Yugoslavia, which had previously been shunned by the Soviet Union due to its anti-Stalinist stance, and Greece. The trials and executions of Traicho Kostov and other "Titoists" (though not of Nikola Petkov and other non-Communist victims of the 1947 purges) were officially denounced. The party's militant anti-clericalism was relaxed and the Orthodox Church was no longer targeted as an enemy of the revolution.

The upheavals in Poland and Hungary in 1956 did not spread to Bulgaria, but the Party placed firm restrictions on publicizing views considered to be anti-socialist or seditious to prevent any such outbreaks. In the 1960s some economic reforms were adopted, which allowed the free sale of production that exceeded planned amounts. The country became the most popular tourist destination for people in the Eastern Bloc. Bulgaria also had a large production basis for commodities such as cigarettes and chocolate, which were hard to obtain in other socialist countries.

Yugov retired in 1962, and Zhivkov then became Prime Minister as well as Party Secretary. He survived the Soviet leadership's transition from Khrushchev to Brezhnev in 1964, and in 1968 again demonstrated his loyalty to the Soviet Union by taking a formal part in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968; that is, he sent a limited number of troops for attendance but not for actually taking part in the bringing down of the Prague Spring. At this point Bulgaria became generally regarded as the Soviet Union's most loyal Eastern European ally.

In 1971, with the adoption of a new Constitution, Zhivkov was promoted to Head of State (Chairman of the State Council) and Stanko Todorov to Prime Minister.

In 1978, Bulgaria attracted widespread international attention when the exiled dissident writer Georgi Markov was accosted on a London street by a stranger who rammed his leg with the tip of an umbrella. Markov died shortly afterwards of ricin poisoning and it was believed that he had been the victim of the Bulgarian secret service, a suspicion confirmed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union when KGB documents were released revealing that they had worked together with Bulgaria to arrange Markov's demise.

End of the People's Republic

Although Zhivkov was never in the Stalinist mold, by the 1980s the conservatives held influence over the government and the administration was very autocratic. Some social and cultural liberalization and progress was led by Lyudmila Zhivkova, Todor's daughter, who however became a source of strong disapproval and annoyance to the Communist Party due to her unorthodox lifestyle which included the practicing of Eastern religions. She died in 1981 a week short of her 39th birthday, and it was rumored, but never proven, that the secret police had her assassinated.

This autocracy was shown most notably in a campaign of forced assimilation against the ethnic Turkish minority, who were forbidden to speak the Turkish language[6] and were forced to adopt Bulgarian names in the winter of 1984. The issue strained Bulgaria's economic relations with the West. The 1989 expulsion of Turks from Bulgaria caused a significant drop in agricultural production in the southern regions due to the loss of around 300,000 workers.[7]

By the time the impact of Mikhail Gorbachev's reform program in the Soviet Union was felt in Bulgaria in the late 1980s, the Communists, like their leader, had grown too feeble to resist the demand for change for long. Liberal outcry at the breakup of an environmental demonstration in Sofia in October 1989 broadened into a general campaign for political reform. More moderate elements in the Communist leadership reacted promptly by deposing Zhivkov and replacing him with foreign minister Petar Mladenov on November 10, 1989.

This swift move, however, gained only a short respite for the Communist Party and prevented revolutionary change. Mladenov promised to open up the regime, even going as far as to say that he supported multi-party elections. However, demonstrations throughout the country brought the situation to a head. On December 11, Mladenov went on national television to announce the Communist Party would cede its monopoly over the political system. On January 15, 1990, the National Assembly formally amended the legal code to abolish the Communist Party's "leading role." In June 1990, the first multi-party elections since 1939 were held, thus paving Bulgaria's way to multi-party system. Finally on 15 November 1990, the 7th Grand National Assembly voted to change the country's name to the Republic of Bulgaria and removed the Communist state emblem from the national flag.[8]

Government and politics

The People's Republic of Bulgaria was a one-party Communist state. The Bulgarian Communist Party created an extensive nomenklatura on each organizational level. The constitution was changed several times, with the Zhivkov Constitution being the longest-lived. According to article 1, "The People's Republic of Bulgaria is a socialist state, headed by the working people of the village and the city. The leading force in society and politics is the Bulgarian Communist Party."

The PRB functioned as a one-party people's republic, with the People's Committees representing local self-governing. Their role was to exercise Party decisions in their respective areas, and in the meantime to rely on popular opinion in decision-making. In the late 1980s, the BCP had an estimated peak of 1,000,000 members—more than 10% of the population.

Military

After Bulgaria was proclaimed a people's republic in 1946, the military rapidly adopted a Soviet military doctrine and organization. The country received large amounts of Soviet weaponry, and eventually established a domestic military vehicle production capability. By the year 1988, the Bulgarian People's Army (Българска народна армия) numbered 152,000 men,[9] serving in four different branches - Land Forces, Navy, Air and Air Defense Forces, and Missile Forces.

The BPA operated an impressive amount of equipment for the country's size - 3,000 tanks, 2,000 armored vehicles, 2,500 large caliber artillery systems, over 500 combat aircraft, 33 combat vessels, as well as 67 Scud missile launchers, 24 SS-23 launchers and dozens of FROG-7 artillery rocket launchers.[10][11][12]

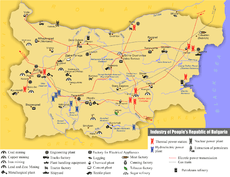

Economy

The economy of the PRB was a centrally planned economy, similar to those in other COMECON states. In the mid-1940s, when the collectivisation process began, Bulgaria was a primarily agrarian state, with some 80% of its population located in rural areas. Production facilities of all sectors were nationalised, although it was not until Vulko Chervenkov that private economic activity was completely scrapped.

Despite negative effects in some other countries, the productivity of Bulgarian agriculture increased rapidly after collectivisation. Large-scale mechanisation resulted in an immense growth in labour productivity.[13] A vast amount of government subsidies were spent each year to cover the losses from the artificially lowered consumer prices.

Chervenkov's Stalinist policy led to a massive industrialisation and development of the energy sector, which is one of Bulgaria's most advanced economic sectors to date. His rule lasted from 1950 to 1956, and saw the construction of dozens of dams and hydroelectric powerplants, chemical works, Elatsite gold and copper mine, and many others. The war-time coupon system was abolished, healthcare and education were made free. All this was achieved with strict government control and organization, prisoner brigades from the labor camps and the Bulgarian Brigadier Movement - a youth labor movement where young people worked voluntarily on construction projects.

Bulgaria was also very involved in computer construction, which earned it the nickname "Silicon Valley of the Eastern Bloc."[15] Bulgarian engineers developed the first Bulgarian computer, the Vitosha,[16] as well as the Pravetz computers, and because of this, it is currently the only Balkan Country to operate a supercomputer, a Blue Gene/P.[15]

In the 1960s, Todor Zhivkov introduced a number of reforms which had a positive effect on the country's economy. He preserved the planned economy, but also put emphasis on light industry, agriculture, tourism, as well as on Information Technology in the 1970s and the 1980s.[17] Surplus agricultural production could be sold freely, prices were lowered even more, and new equipment for light industrial production was imported. Bulgaria also became the first Communist country to purchase a license from Coca-Cola in 1965, the product had the trademark logo in Cyrillic.[18]

Despite being very stable, the economy shared the same drawbacks of other countries from Eastern Europe - it traded almost entirely with the Soviet Union (more than 60%) and planners did not take into account whether there were markets for some of the goods produced. This resulted in surpluses of certain products, while other commodities were in deficit.

Apart from the Soviet Union, other main trade partners were East Germany and Czechoslovakia, but non-European countries such as Mongolia and various African countries were also large-scale importers of Bulgarian goods. The country also enjoyed good trade relations with various non-Communist developed countries, most notably West Germany and Italy.[19] In order to combat the low quality of many goods, a comprehensive State standard system was introduced in 1970, which included precise and strict quality requirements for all sorts of products, machines and buildings.

The People's Republic of Bulgaria had an average GDP per capita for an Eastern Bloc country. A comparative table is given below. At least on paper, average purchasing power was one of the lowest in the Eastern Bloc, mostly due to the larger availability of commodities than in other socialist countries. Workers employed abroad often received higher payments, thus could afford a wider range of goods to purchase. According to official figures, in 1988 100 out of 100 households had a television set, 95 out of 100 had a radio, 96 out of 100 had a refrigerator, and 40 out of 100 had an automobile.[20]

Per Capita GDP (1990 $[21]) 1950 1973 1989[22] 1990 United States $9,561 $16,689 n/a $23,214 Finland $4,253 $11,085 $16,676 $16,868 Austria $3,706 $11,235 $16,305 $16,881 Italy $3,502 $10,643 $15,650 $16,320 Czechoslovakia $3,501 $7,041 $8,729 $8,895 (Czech)

$7,762 (Slovak)Soviet Union $2,834 $6,058 n/a $6,871 Hungary $2,480 $5,596 $6,787 $6,471 Poland $2,447 $5,334 n/a $5,115 Spain $2,397 $8,739 $11,752 $12,210 Portugal $2,069 $7,343 $10,355 $10,852 Greece $1,915 $7,655 $10,262 $9,904 Bulgaria $1,651 $5,284 $6,217 $5,552 Yugoslavia $1,585 $4,350 $5,917 $5,695 Romania $1,182 $3,477 $3,890 $3,525 Albania $1,101 $2,252 n/a $2,482

Automobile industry

Since 1965 in People's Republic of Bulgaria many companies from Western Europe choose Bulgaria to build their factories to sell their automobiles in the countries which were in the eastern bloc. Renault and Citroen from France, and Fiat and Alfa Romeo from Italy tried to convince Bulgaria for a partnership, but People's Republic of Bulgaria made deals only with Renault and Fiat.

- Bulgarrenault started in 1966 until 1971 making cars based on Renault 8 and Renault 10. The factories were in Plovdiv. In the end around 6500 cars were produced. The Bulgarian version of Alpine A110 was also made under the marque Bulgaralpine.

- In 1967 started the building of Pirin-Fiat constructing around 730 cars until 1971 from the models Fiat 850 and Fiat 124.

- In 1968 a contract was signed between the Bulgarian government and Moskvitch for building Moskvitch 408 and later Moskvitch 2141 (from which around 12,000 cars were produced by 1990).

Culture

Culture in the People's Republic of Bulgaria was strictly controlled and regulated by the government, although there have been some periods of liberalization (meaning entrance in Bulgaria of Western literature, music, etc.). The thaw in intellectual life had continued from 1951 until the middle of the decade. Vulko Chervenkov's resignation and the literary and cultural flowering in the Soviet Union created expectations that the process would continue, but the Hungarian revolution of fall 1956 frightened the Bulgarian leadership away from encouragement of dissident intellectual activity.

In response to events in Hungary, Chervenkov was appointed minister of education and culture; in 1957 and 1958, he purged the leadership of the Bulgarian Writers' Union and dismissed liberal journalists and editors from their positions. His crackdowns effectively ended the "Bulgarian thaw" of independent writers and artists inspired by Khrushchev's 1956 speech against Stalinism.[23]

References

- ↑ Rao, B. V. (2006), History of Modern Europe Ad 1789-2002: A.D. 1789-2002, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- ↑ http://www.country-data.com/cgi-bin/query/r-1832.html

- ↑ Hanna Arendt Center in Sofia, with Dinyu Sharlanov and Venelin I. Ganev. Crimes Committed by the Communist Regime in Bulgaria. Country report. "Crimes of the Communist Regimes" Conference. 24–26 February 2010, Prague.

- ↑ Valentino, Benjamin A (2005). Final solutions: mass killing and genocide in the twentieth century. Cornell University Press. pp. 91–151.

- ↑ Rummel, Rudolph, Statistics of Democide, 1997.

- ↑ Crampton, R.J., A Concise History of Bulgaria, 2005, pp.205, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ "1990 CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ "UK Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate Country Assessment - Bulgaria". United Kingdom Home Office. 1 March 1999. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Bulgaria - Military Personnel

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+bg0208)

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+bg0209)

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+bg0210)

- ↑ Agricultural policies in Bulgaria in post Second World War years, p.5

- ↑ IT Services: Rila Establishes Bulgarian Beachhead in UK, findarticles.com, June 24, 1999

- 1 2 Google Books: The European Union, "By Wikipedians," pg. 428

- ↑ Bulgarian Wikipedia article: Витоша (компютър)

- ↑ "Bulgaria: Soviet Silicon Valley Revived". Novinite.com. Sofia News Agency. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ Coca-Cola.bg

- ↑ (Dead Link)

- ↑ Living Standards

- ↑ Madison 2006, p. 185

- ↑ Teichova, Alice; Matis, Herbert (2003). Nation, State, and the Economy in History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-521-79278-9.

- ↑ Intellectual life

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to People's Republic of Bulgaria. |

- Maddison, Angus (2006), The world economy, OECD Publishing, ISBN 92-64-02261-9

External links

- The Cold War International History Project's Document Collection on Bulgaria During the Cold War

- http://www.osaarchivum.org/files/holdings/300/8/3/text/125-2-115.shtml

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

.svg.png)