Penal transportation

Transportation or penal transportation is the sending of convicted criminals or other persons regarded as undesirable to a penal colony. For example, France transported convicts to Devil's Island and New Caledonia and England transported convicts, political prisoners and prisoners of war from Scotland and Ireland to its colonies in the Americas (from the 1610s until the American Revolution in the 1770s) and Australia (1788–1868), the practice becoming available in Scotland consequent to the Union of 1707 but used less than in England.

Most of this article deals with transportation from Great Britain.

Origin and implementation

Banishment or forced exile from a polity or society has been used as a punishment since Roman times or before. It removed the offender from society, possibly permanently, but was seen as a more merciful punishment than execution.

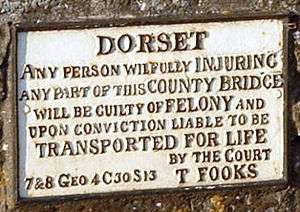

Under English Law, transportation was a sentence imposed for felony, and was typically imposed for offences for which capital punishment was deemed too severe: for example, forgery of a document was a capital crime until the 1820s, when the penalty was reduced to transportation. The sentence was imposed for life or for a set period of years. If imposed for a period of years, the offender was permitted to return home after serving out his time, but had to make his own way back. Many offenders thus stayed in the colony as free persons, and might obtain employment as jailers or other servants of the penal colony.

Transportation was not used by Scotland before the Union. Post-Union laws made by the United Kingdom Parliament extended the availability to Scotland, but it remained little used[1] under Scots Law until the early 19th century.

In Australia, a convict who had served part of his time might apply for a ticket of leave, permitting some prescribed freedoms. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family, and to contribute to the development of the colony.

Historical background

The trend towards more flexibility of sentencing

_-_SLV_H99.220-2568.jpg)

In the 17th and 18th centuries the choice of sentences available to judges for convicted criminals in England was very limited. In particular, a large number of offences were punishable by execution, usually by hanging. Benefit of clergy, originally an exemption from civil law for clergymen only, had developed into a legal fiction by which many ("clergyable") offenders could avoid execution.[2] Many offenders were pardoned as it was considered unreasonable to execute them for relatively minor offences, but equally it was unreasonable for them to escape punishment entirely. Transportation was introduced as an alternative punishment, although legally it was considered a condition of a pardon, rather than a sentence in itself.[3] Convicts who represented a menace to the community were sent away to distant lands. A secondary aim was to discourage crime for fear of being transported. Transportation was also described as a public exhibition of the king's mercy. It was a solution to a real problem in the penal system.[4] There was also the possibility that transported convicts could be rehabilitated and reformed by starting a new life in the colonies.

The system started to change inexorably between 1660 and 1720, with attempts to replace the simple discharge of clergyable felons after branding on their thumb. There were various influential agents of change: judges' discretionary powers influenced the law significantly, but the king's and Privy Council's opinions were decisive in granting a royal pardon from execution.[5] In 1615, in the reign of James I, a committee of the Council had already obtained the power to choose from the prisoners those that deserved pardon and, consequently, transportation to the colonies. Convicts were chosen carefully: the Acts of the Privy Council showed that prisoners "for strength of bodie or other abilities shall be thought fitt to be ymploied in forraine discoveries or other services beyond the Seas".[6]

The system changed one step at a time: after that first experiment, a bill was proposed to the House of Commons in February 1663 to allow the transporting of felons, and was followed by another bill presented to the Lords to allow the transportation of criminals convicted of felony within clergy or petty larceny. These bills failed, but it was clear that change was needed.[7] Transportation was not a sentence in itself, but could be arranged by indirect means. The reading test, crucial for the benefit of clergy, was a fundamental feature of the penal system, but in order to prevent its abuse, this pardoning process was used more strictly. Prisoners were carefully selected for transportation based on information about their character and previous criminal record. It was arranged that they fail the reading test, but they were then reprieved and held in jail, without bail, to allow time for a royal pardon (subject to transportation) to be organised.[8]

Transportation as a commercial transaction

Transportation became a business: merchants chose from among the prisoners on the basis of the demand for labour and their likely profits. They obtained a contract from the sheriffs, and after the voyage to the colonies they sold the convicts as indentured servants. The payment they received also covered the jail fees, the fees for granting the pardon, the clerk's fees, and everything necessary to authorise the transportation.[9] These arrangements for transportation continued until the end of the 17th century and beyond, but they diminished in 1670 due to certain complications. The colonial opposition was one of the main obstacles: colonies were unwilling to collaborate in accepting prisoners: the convicts represented a danger to the colony and were unwelcome. Maryland and Virginia enacted laws to prohibit transportation in 1670, and the king was persuaded to respect these.[10]

The penal system was also influenced by economics: the profits obtained from convicts' labour boosted the economy of the colonies and, consequently, of England. Nevertheless, it could be argued that transportation was economically deleterious because the aim was to enlarge population, not diminish it;[11] but the character of an individual convict was likely to harm the economy. King William's War (1688–1697) (part of the Nine Years' War) and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) adversely affected merchant shipping and hence transportation. In the post-war period there was more crime[12] and hence potentially more executions, and something needed to be done. In the reigns of Queen Anne (1702–14) and George I (1714–27), transportation was not easily arranged, but imprisonment was not considered enough to punish hardened criminals or those who had committed capital offences, so transportation was the preferred punishment.[13]

Transportation Act 1717

There were several obstacles to the use of transportation. In 1706 the reading test for claiming benefit of clergy was abolished (5 Anne c. 6). This allowed judges to sentence "clergyable" offenders to a workhouse or a house of correction.[14] But the punishments that then applied were not enough of a disincentive to commit crime: another solution was needed. The Transportation Act was introduced into the House of Commons in 1717 under the Whig government. It legitimised transportation as a direct sentence, thus simplifying the penal process.[15]

Non-capital convicts (clergyable felons usually destined for branding on the thumb, and petty larceny convicts usually destined for public whipping)[16] were directly sentenced to transportation to the American colonies for seven years. A sentence of fourteen years was imposed on prisoners guilty of capital offences pardoned by the king. Returning from the colonies before the stated period was a capital offence.[17] The bill was introduced by William Thomson, the Solicitor General, who was "the architect of the transportation policy".[18] Thomson, a supporter of the Whigs, was Recorder of London and became a judge in 1729. He was a prominent sentencing officer at the Old Bailey and the man who gave important information about capital offenders to the cabinet.[19]

One reason for the success of this Act was that transportation was financially costly. The system of sponsorship by merchants had to be improved. Initially the government rejected Thomson's proposal to pay merchants to transport convicts, but three months after the first transportation sentences were pronounced at the Old Bailey, his suggestion was proposed again, and the Treasury contracted Jonathan Forward, a London merchant, for the transportation to the colonies.[20] The business was entrusted to Forward in 1718: he was paid £3 (£5 in 1727) for each prisoner transported overseas. The Treasury also paid for the transportation of prisoners from the Home Counties.[21]

The "Felons' Act" (as the Transportation Act was called) was printed and distributed in 1718, and in April twenty-seven men and women were sentenced to transportation[22] The Act led to significant changes: both petty and grand larceny were punished by transportation (seven years), and the sentence for any non-capital offence was at the judge's discretion.[23] In 1723 an Act was presented in Virginia to discourage transportation by establishing complex rules for the reception of prisoners, but the reluctance of colonies did not stop transportation.[24]

In a few cases before 1734, the court changed sentences of transportation to sentences of branding on the thumb or whipping, by convicting the accused for lesser crimes than those of which they were accused.[25][26] This manipulation phase came to an end in 1734. With the exception of those years, the Transportation Act led to a decrease in whipping of convicts, thus avoiding potentially inflammatory public displays. Clergyable discharge continued to be used when the accused could not be transported for reasons of age or infirmity.[27]

Gender and age group

Penal transportation was not limited to men or even to adults. Men, women and children were sentenced to transportation, but its implementation varied by gender and age. From 1660 to 1670, highway robbery, burglary and horse theft were the offences most often punishable with transportation for men. In those years, five of the nine women who were transported after being sentenced to death were guilty of simple larceny, an offence for which benefit of clergy was not available for women until 1692.[28] Also, merchants preferred young and able-bodied men for whom there was a demand in the colonies.

All these factors meant that most women and children were simply left in jail.[29] Some magistrates supported a proposal to release women who could not be transported, but this solution was considered absurd: this caused the Lords Justices to order that no distinction be made between men and women.[30] Women were sent to the Leeward Islands, the only colony that accepted them, and the government had to pay to send them overseas.[31] In 1696 Jamaica refused to welcome a group of prisoners because most of them were women; Barbados similarly accepted convicts but not "women, children nor other infirm persons".[32]

Thanks to transportation, the number of men whipped and released diminished: but whipping and discharge was chosen more often for women. The reverse was true when women were sentenced for a capital offence, but actually served a lesser sentence due to a manipulation of the penal system: one advantage of this sentence was that they could be discharged thanks to benefit of clergy while men were whipped.[33] Women with young children were also supported since transportation unavoidably separated them.[34] The facts and numbers revealed how transportation was less frequently applied to women and children because they were usually guilty of minor crimes and they were considered a minimal threat to the community.[35]

The end of transportation

The outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) halted transportation: instead men were sentenced to hard labour and women were imprisoned. When transportation resumed in 1787, Australian colonies were chosen: since transportation involved the terrible experience of exile, it was considered more severe than imprisonment.[36] At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation for life became the maximum penalty for several offences which had previously been punishable by death.[36] Sentences of transportation became less common in 1840 since the system was perceived to be a failure: crime continued at high levels, people were not dissuaded from committing felonies, and the conditions of convicts in the colonies were inhumane. In 1857 the Penal Servitude Act gave judges the power to sentence prisoners destined for transportation to penal servitude for less than fourteen years.[36] Because of all these events, transportation gradually came to an end.

North America

From the early 1600s until the American Revolution of 1776, the British colonies in North America received transported British criminals. In the 17th century transportation was carried out at the expense of the convicts or the shipowners. The Transportation Act 1717 allowed courts to sentence convicts to seven years' transportation to America. In 1720, an extension authorised payments by the Crown to merchants contracted to take the convicts to America. Under the Transportation Act, returning from transportation was a capital offence.[36][37] The number of convicts transported to North America is not verified although it has been estimated to be 50,000 by John Dunmore Lang and 120,000 by Thomas Keneally. Many prisoners were taken in battle from Ireland and Scotland and sold into indentured servitude, usually for a number of years.[38]

The American Revolution brought transportation to an end. The remaining British colonies in what is now Canada were close to the new United States of America, thus prisoners sent there might become hostile to British authorities. British gaols became overcrowded, and dilapidated ships moored in various ports were pressed into service as floating gaols. As a result, the British Government decided to look elsewhere.

Australia

In 1787, the "First Fleet" departed from England to establish the first British settlement in Australia, as a penal colony. The fleet arrived at Port Jackson (Sydney) on 26 January 1788, a date now celebrated as Australia Day. Norfolk Island was a convict penal settlement from 1788 until 1794, and again from 1824 to 1847. They also brought boats containing food and animals from London. The ships and boats would explore the coast of Australia by sailing all around it looking for suitable farming land and resources. In 1803, Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) was also settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (Queensland) in 1824. The other Australian colonies were "free settlements", as non-convict colonies were known. However, the Swan River Colony (Western Australia) accepted transportation from England and Ireland in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage. Until the massive influx of immigrants during the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, the settler population had been dominated by English and Irish convicts and their descendants. However, compared to America, Australia received many more English prisoners.

Transportation from Britain and Ireland officially ended in 1868, although it had become uncommon several years earlier.[39]

Other

New Caledonia became a French penal colony from the 1860s until the end of the transportations in 1897. About 22,000 criminals and political prisoners (most notably Communards) were sent to New Caledonia.

In British colonial India, opponents of British rule were transported to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman islands.

The most famous transported prisoner is probably French army officer Alfred Dreyfus, wrongly convicted of treason in a trial in 1894, held in an atmosphere of antisemitism. He was sent to Devil's Island, a French penal colony in Guiana. The case became a cause celebre known as the Dreyfus Affair, and Dreyfus was fully exonerated in 1906.

Literature

The British author William Somerset Maugham set a number of his short stories in the French Caribbean penal colonies. Franz Kafka's story "In the Penal Colony", set in an unidentified location, was later adapted for several other media, including an opera by Philip Glass.

One of the key characters in Charles Dickens' novel Great Expectations is Abel Magwitch, the escaped convict who Pip helps in the opening pages of the novel, and who later turns out to be Pip's secret benefactor—the source of his "great expectations". Manwitch, who had been apprehended shortly after the young Pip had helped him, was thereafter sentenced to transportation for life to New South Wales in Australia. While so exiled, he earned the fortune that he later would use to help Pip. Further, it was Manwitch's desire to see the "gentleman" that Pip had become that motivated him to illegally return to England, which ultimately led to his arrest and death.

Timberlake Wertenbaker's play Our Country's Good, based on Thomas Keneally's novel The Playmaker, is set in the first Australian penal colony.

My Transportation for Life, Indian freedom fighter Veer Savarkar's memoir of his imprisonment, is set in the British Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands.

The novel Papillon tells the story of Henri Charrière, a French criminal convicted on 26 October 1931 as a murderer, and exiled to the French Guinea penal colony on Devil's Island. A film adaptation of the book was made in 1973, starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

Penal transportation, typically to other planets, sometimes appears in works of science fiction. A classic example is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert Heinlein, in which convicts and political dissidents are transported to lunar colonies. In Heinlein's book, a sentence of lunar transportation is necessarily permanent, as the long-term physiological effects of the moon's weak surface gravity (about one-sixth that of Earth) leave "loonies" unable to return safely to Earth.

See also

- Exile

- Deportation

- Prison

- Devil's Island

- Millbank Prison

- Australian history before 1901

- Convicts in Australia

- Australian penal colonies

- Convict ship

Notes

- ↑ Donnachie, Ian (1984), "Scottish Criminals and Transportation to Australia 1786–1852", journal Scottish Economic and Social History

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 470

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 472

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 473

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 471

- ↑ Acts of the Privy Council (Colonial), vol. I , pp. 310, 314-15

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, pp. 471–472

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 475

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 479

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 479

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 480

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 500

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 502

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 502

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 503

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 428

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 503

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 429

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 426

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 430

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 504

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 432

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 506

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 505

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 435

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 439

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 447

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 474

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 479

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 483

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 482

- ↑ Beattie, 1986, p. 481

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 444

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 444

- ↑ Beattie, 2001, p. 435

- 1 2 3 4 Punishments at the Old Bailey, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, retrieved November 2015

- ↑ R v Powell, Sixth session Proceedings of the Old Bailey 10th July, 1805 t18050710-23, page 401 (Old Bailey 10 July 1805).

- ↑ Ekirch, A. Roger (1990), Bound for America: The Transportation of British Convicts to the Colonies, 1718–1775, Oxford University, ISBN 0-19-820211-3

- ↑ McConville, Sean (1981), A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750–1877, London: Boston & Henley, pp. 381–385, ISBN 0-7100-0694-2

References

- Pardons & Punishments: Judges Reports on Criminals, 1783 to 1830: HO (Home Office) 47 Volumes 304 and 305, List and Index Society, The [British ] National Archives

- Beattie, J.M. (1986), Crime and the Courts in England 1660–1800, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820058-7.

- Beattie, J.M. (2001), Policing and Punishment in London 1660–1750, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820867-7.

- Ekirch, A. Roger (1987), Bound for America. The transportation of British convicts to the colonies, 1718–1775, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820092-7.

- Hitchcock, Tim; Shoemaker, Robert (2006), Tales From the Hanging Court, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-0-340-91375-8.

- Punishments at the Old Bailey, Old Bailey Proceedings Online, retrieved November 2015

- Robson, L. L. (1965), The Convict Settlers of Australia, Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, ISBN 0-522-83994-0.

- Sharpe, J. A. (1999), Crime in early modern England 1550–1750, Harlow, Essex: Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-23889-3.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. (1999), Prosecution and Punishment. Petty crime and the law in London and rural Middlesex, c. 1660–1725, Harlow, Essex: Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-23889-3.

External links

- UK National archives

- Convict life – State Library of NSW

- Convict Transportation Registers

- Convict Queenslanders