Pell's equation

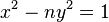

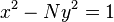

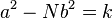

Pell's equation (also called the Pell–Fermat equation) is any Diophantine equation of the form

where n is a given positive nonsquare integer and integer solutions are sought for x and y. In Cartesian coordinates, the equation has the form of a hyperbola; solutions occur wherever the curve passes through a point whose x and y coordinates are both integers, such as the trivial solution with x = 1 and y = 0. Joseph Louis Lagrange proved that, as long as n is not a perfect square, Pell's equation has infinitely many distinct integer solutions. These solutions may be used to accurately approximate the square root of n by rational numbers of the form x/y.

This equation was first studied extensively in India, starting with Brahmagupta, who developed the chakravala method to solve Pell's equation and other quadratic indeterminate equations in his Brahma Sphuta Siddhanta in 628, about a thousand years before Pell's time. His Brahma Sphuta Siddhanta was translated into Arabic in 773 and was subsequently translated into Latin in 1126. Bhaskara II in the 12th century and Narayana Pandit in the 14th century both found general solutions to Pell's equation and other quadratic indeterminate equations. Solutions to specific examples of the Pell equation, such as the Pell numbers arising from the equation with n = 2, had been known for much longer, since the time of Pythagoras in Greece and to a similar date in India. The name of Pell's equation arose from Leonhard Euler's mistakenly attributing Lord Brouncker's solution of the equation to John Pell.[1]

For a more detailed discussion of much of the material here, see Lenstra (2002) and Barbeau (2003).

History

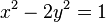

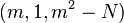

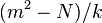

As early as 400 BC in India and Greece, mathematicians studied the numbers arising from the n = 2 case of Pell's equation,

and from the closely related equation

because of the connection of these equations to the square root of two.[2] Indeed, if x and y are positive integers satisfying this equation, then x/y is an approximation of √2. The numbers x and y appearing in these approximations, called side and diameter numbers, were known to the Pythagoreans, and Proclus observed that in the opposite direction these numbers obeyed one of these two equations.[2] Similarly, Baudhayana discovered that x = 17, y = 12 and x = 577, y = 408 are two solutions to the Pell equation, and that 17/12 and 577/408 are very close approximations to the square root of two.

Later, Archimedes approximated the square root of 3 by the rational number 1351/780. Although he did not explain his methods, this approximation may be obtained in the same way, as a solution to Pell's equation.[2] Archimedes' cattle problem involves solving a Pellian equation, though it is unclear whether this problem is really due to Archimedes.

Around AD 250, Diophantus considered the equation

where a and c are fixed numbers and x and y are the variables to be solved for. This equation is different in form from Pell's equation but equivalent to it. Diophantus solved the equation for (a,c) equal to (1,1), (1,−1), (1,12), and (3,9). Al-Karaji, a 10th-century Persian mathematician, worked on similar problems to Diophantus.

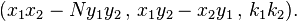

In Indian mathematics, Brahmagupta discovered that

(see Brahmagupta's identity). Using this, he was able to "compose" triples  and

and  that were solutions of

that were solutions of  , to generate the new triple

, to generate the new triple

and

and

Not only did this give a way to generate infinitely many solutions to  starting with one solution, but also, by dividing such a composition by

starting with one solution, but also, by dividing such a composition by  , integer or "nearly integer" solutions could often be obtained. For instance, for

, integer or "nearly integer" solutions could often be obtained. For instance, for  , Brahmagupta composed the triple

, Brahmagupta composed the triple  (since

(since  ) with itself to get the new triple

) with itself to get the new triple  . Dividing throughout by 64 ('8' for

. Dividing throughout by 64 ('8' for  and

and  , being squared) gave the triple

, being squared) gave the triple  , which when composed with itself gave the desired integer solution

, which when composed with itself gave the desired integer solution  . Brahmagupta solved many Pell equations with this method; in particular he showed how to obtain solutions starting from an integer solution of

. Brahmagupta solved many Pell equations with this method; in particular he showed how to obtain solutions starting from an integer solution of  for

for  = ±1, ±2, or ±4.[3]

= ±1, ±2, or ±4.[3]

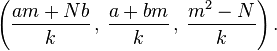

The first general method for solving the Pell equation (for all N) was given by Bhaskara II in 1150, extending the methods of Brahmagupta. Called the chakravala (cyclic) method, it starts by composing any triple  (that is, one which satisfies

(that is, one which satisfies  ) with the trivial triple

) with the trivial triple  to get the triple

to get the triple  , which can be scaled down to

, which can be scaled down to

When  is chosen so that

is chosen so that  is an integer, so are the other two numbers in the triple. Among such

is an integer, so are the other two numbers in the triple. Among such  , the method chooses one that minimizes

, the method chooses one that minimizes  , and repeats the process. This method always terminates with a solution (proved by Lagrange in 1768). Bhaskara used it to give the solution

, and repeats the process. This method always terminates with a solution (proved by Lagrange in 1768). Bhaskara used it to give the solution  =1766319049,

=1766319049,  =226153980 to the notorious

=226153980 to the notorious  = 61 case.[3]

= 61 case.[3]

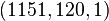

Several European mathematicians rediscovered how to solve Pell's equation in the 17th century, apparently unaware that it had been solved almost a thousand years earlier in India. Fermat found how to solve the equation and in a 1657 letter issued it as a challenge to English mathematicians. In a letter to Digby, Bernard Frénicle de Bessy said that Fermat found the smallest solution for  up to 150, and challenged John Wallis to solve the cases

up to 150, and challenged John Wallis to solve the cases  = 151 or 313. Both Wallis and Lord Brouncker gave solutions to these problems, though Wallis suggests in a letter that the solution was due to Brouncker.

= 151 or 313. Both Wallis and Lord Brouncker gave solutions to these problems, though Wallis suggests in a letter that the solution was due to Brouncker.

Pell's connection with the equation is that he revised Thomas Branker's translation (Rahn 1668) of Johann Rahn's 1659 book "Teutsche Algebra" into English, with a discussion of Brouncker's solution of the equation. Euler mistakenly thought that this solution was due to Pell, as a result of which he named the equation after Pell.

The general theory of Pell's equation, based on continued fractions and algebraic manipulations with numbers of the form  was developed by Lagrange in 1766–1769.[4]

was developed by Lagrange in 1766–1769.[4]

Solutions

Fundamental solution via continued fractions

Let  denote the sequence of convergents to the regular continued fraction for

denote the sequence of convergents to the regular continued fraction for  . This sequence is unique. Then the pair (x1,y1) solving Pell's equation and minimizing x satisfies x1 = hi and y1 = ki for some i. This pair is called the fundamental solution. Thus, the fundamental solution may be found by performing the continued fraction expansion and testing each successive convergent until a solution to Pell's equation is found.

. This sequence is unique. Then the pair (x1,y1) solving Pell's equation and minimizing x satisfies x1 = hi and y1 = ki for some i. This pair is called the fundamental solution. Thus, the fundamental solution may be found by performing the continued fraction expansion and testing each successive convergent until a solution to Pell's equation is found.

As Lenstra (2002) describes, the time for finding the fundamental solution using the continued fraction method, with the aid of the Schönhage–Strassen algorithm for fast integer multiplication, is within a logarithmic factor of the solution size, the number of digits in the pair (x1,y1). However, this is not a polynomial time algorithm because the number of digits in the solution may be as large as √n, far larger than a polynomial in the number of digits in the input value n (Lenstra 2002).

Additional solutions from the fundamental solution

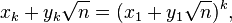

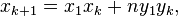

Once the fundamental solution is found, all remaining solutions may be calculated algebraically from

expanding the right side, equating coefficients of  on both sides, and equating the other terms on both sides. This yields the recurrence relations

on both sides, and equating the other terms on both sides. This yields the recurrence relations

Concise representation and faster algorithms

Although writing out the fundamental solution (x1,y1) as a pair of binary numbers may require a large number of bits, it may in many cases be represented more compactly in the form

using much smaller coefficients ai, bi, and ci.

For instance, Archimedes' cattle problem may be solved using a Pell equation, the fundamental solution of which has 206545 digits if written out explicitly, the value is 776027140648...719455081800. However, instead of writing the solution as a pair of numbers, it may be written using the formula

where

and  and

and  only have 45 and 41 decimal digits, respectively. Alternatively, one may write even more concisely

only have 45 and 41 decimal digits, respectively. Alternatively, one may write even more concisely

(Lenstra 2002).

In fact, it is equivalent to solving the Pell equation  . (

. ( )

)

Methods related to the quadratic sieve approach for integer factorization may be used to collect relations between prime numbers in the number field generated by √n, and to combine these relations to find a product representation of this type. The resulting algorithm for solving Pell's equation is more efficient than the continued fraction method, though it still does not take polynomial time. Under the assumption of the generalized Riemann hypothesis, it can be shown to take time

where N = log n is the input size, similarly to the quadratic sieve (Lenstra 2002).

Quantum algorithms

Hallgren (2007) showed that a quantum computer can find a product representation, as described above, for the solution to Pell's equation in polynomial time. Hallgren's algorithm, which can be interpreted as an algorithm for finding the group of units of a real quadratic number field, was extended to more general fields by Schmidt & Völlmer (2005).

Example

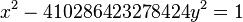

As an example, consider the instance of Pell's equation for n = 7; that is,

The sequence of convergents for the square root of seven are

h / k (Convergent) h2 −7k2 (Pell-type approximation) 2 / 1 −3 3 / 1 +2 5 / 2 −3 8 / 3 +1

Therefore, the fundamental solution is formed by the pair (8, 3). Applying the recurrence formula to this solution generates the infinite sequence of solutions

- (1, 0); (8, 3); (127, 48); (2024, 765); (32257, 12192); (514088, 194307); (8193151, 3096720); (130576328, 49353213); ... (sequence A001081 (x) and A001080 (y) in OEIS)

The smallest solution can be very large. For example, the smallest solution to  is (32188120829134849, 1819380158564160), and this is the equation which Frenicle challenged Wallis to solve.[5] Values of n such that the smallest solution of

is (32188120829134849, 1819380158564160), and this is the equation which Frenicle challenged Wallis to solve.[5] Values of n such that the smallest solution of  is greater than the smallest solution for any smaller value of n are

is greater than the smallest solution for any smaller value of n are

- 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 29, 46, 53, 61, 109, 181, 277, 397, 409, 421, 541, 661, 1021, 1069, 1381, 1549, 1621, 2389, 3061, 3469, 4621, 4789, 4909, 5581, 6301, 6829, 8269, 8941, 9949, ... (sequence A033316 in OEIS)

(For these records, see ![]() A033315 (x), and

A033315 (x), and ![]() A033319 (y)).

A033319 (y)).

The smallest solution of Pell equations

The following is a list of the smallest solution to  with n ≤ 128. For square n, there are no solutions except (1, 0). (sequence A002350 (x) and A002349 (y) in OEIS, or

with n ≤ 128. For square n, there are no solutions except (1, 0). (sequence A002350 (x) and A002349 (y) in OEIS, or ![]() A033313 (x) and

A033313 (x) and ![]() A033317 (y) (for nonsquare n))

A033317 (y) (for nonsquare n))

n x y n x y n x y n x y 1 - - 33 23 4 65 129 16 97 62809633 6377352 2 3 2 34 35 6 66 65 8 98 99 10 3 2 1 35 6 1 67 48842 5967 99 10 1 4 - - 36 - - 68 33 4 100 - - 5 9 4 37 73 12 69 7775 936 101 201 20 6 5 2 38 37 6 70 251 30 102 101 10 7 8 3 39 25 4 71 3480 413 103 227528 22419 8 3 1 40 19 3 72 17 2 104 51 5 9 - - 41 2049 320 73 2281249 267000 105 41 4 10 19 6 42 13 2 74 3699 430 106 32080051 3115890 11 10 3 43 3482 531 75 26 3 107 962 93 12 7 2 44 199 30 76 57799 6630 108 1351 130 13 649 180 45 161 24 77 351 40 109 158070671986249 15140424455100 14 15 4 46 24335 3588 78 53 6 110 21 2 15 4 1 47 48 7 79 80 9 111 295 28 16 - - 48 7 1 80 9 1 112 127 12 17 33 8 49 - - 81 - - 113 1204353 113296 18 17 4 50 99 14 82 163 18 114 1025 96 19 170 39 51 50 7 83 82 9 115 1126 105 20 9 2 52 649 90 84 55 6 116 9801 910 21 55 12 53 66249 9100 85 285769 30996 117 649 60 22 197 42 54 485 66 86 10405 1122 118 306917 28254 23 24 5 55 89 12 87 28 3 119 120 11 24 5 1 56 15 2 88 197 21 120 11 1 25 - - 57 151 20 89 500001 53000 121 - - 26 51 10 58 19603 2574 90 19 2 122 243 22 27 26 5 59 530 69 91 1574 165 123 122 11 28 127 24 60 31 4 92 1151 120 124 4620799 414960 29 9801 1820 61 1766319049 226153980 93 12151 1260 125 930249 83204 30 11 2 62 63 8 94 2143295 221064 126 449 40 31 1520 273 63 8 1 95 39 4 127 4730624 419775 32 17 3 64 - - 96 49 5 128 577 51

Connections

Pell's equation has connections to several other important subjects in mathematics.

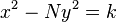

Algebraic number theory

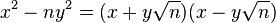

Pell's equation is closely related to the theory of algebraic numbers, as the formula

is the norm for the ring ![\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{n}]](../I/m/e24f9d622bf1230a6ae265794604a4bf.png) and for the closely related quadratic field

and for the closely related quadratic field  . Thus, a pair of integers

. Thus, a pair of integers  solves Pell's equation if and only if

solves Pell's equation if and only if  is a unit with norm 1 in

is a unit with norm 1 in ![\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{n}]](../I/m/e24f9d622bf1230a6ae265794604a4bf.png) . Dirichlet's unit theorem, that all units of

. Dirichlet's unit theorem, that all units of ![\mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{n}]](../I/m/e24f9d622bf1230a6ae265794604a4bf.png) can be expressed as powers of a single fundamental unit (and multiplication by a sign), is an algebraic restatement of the fact that all solutions to the Pell equation can be generated from the fundamental solution. The fundamental unit can in general be found by solving a Pell-like equation but it does not always correspond directly to the fundamental solution of Pell's equation itself, because the fundamental unit may have norm −1 rather than 1 and its coefficients may be half integers rather than integers.

can be expressed as powers of a single fundamental unit (and multiplication by a sign), is an algebraic restatement of the fact that all solutions to the Pell equation can be generated from the fundamental solution. The fundamental unit can in general be found by solving a Pell-like equation but it does not always correspond directly to the fundamental solution of Pell's equation itself, because the fundamental unit may have norm −1 rather than 1 and its coefficients may be half integers rather than integers.

Chebyshev polynomials

Demeyer (2007) mentions a connection between Pell's equation and the Chebyshev polynomials: If Ti (x) and Ui (x) are the Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kind, respectively, then these polynomials satisfy a form of Pell's equation in any polynomial ring R[x], with n = x2 − 1:

Thus, these polynomials can be generated by the standard technique for Pell equations of taking powers of a fundamental solution:

It may further be observed that, if (xi,yi) are the solutions to any integer Pell equation, then xi = Ti (x1) and yi = y1Ui − 1(x1) (Barbeau, chapter 3).

Continued fractions

A general development of solutions of Pell's equation  in terms of continued fractions of

in terms of continued fractions of  can be presented, as the solutions x and y are approximates to the square root of n and thus are a special case of continued fraction approximations for quadratic irrationals.

can be presented, as the solutions x and y are approximates to the square root of n and thus are a special case of continued fraction approximations for quadratic irrationals.

The relationship to the continued fractions implies that the solutions to Pell's equation form a semigroup subset of the modular group. Thus, for example, if p and q satisfy Pell's equation, then

is a matrix of unit determinant. Products of such matrices take exactly the same form, and thus all such products yield solutions to Pell's equation. This can be understood in part to arise from the fact that successive convergents of a continued fraction share the same property: If pk−1/qk−1 and pk/qk are two successive convergents of a continued fraction, then the matrix

has determinant (−1)k.

Størmer's theorem applies Pell equations to find pairs of consecutive smooth numbers. As part of this theory, Størmer also investigated divisibility relations among solutions to Pell's equation; in particular, he showed that each solution other than the fundamental solution has a prime factor that does not divide n.

As Lenstra (2002) describes, Pell's equation can also be used to solve Archimedes' cattle problem.

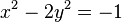

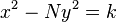

The negative Pell equation

The negative Pell equation is given by

(eq.1)

(eq.1)

It has also been extensively studied; it can be solved by the same method of using continued fractions and will have solutions when the period of the continued fraction has odd length. However we do not know which roots have odd period lengths so we do not know when the negative Pell equation is solvable. But we can eliminate certain n since a necessary but not sufficient condition for solvability is that n is not divisible by a prime of form 4m + 3. Thus, for example, x2 − 3py2 = −1 is never solvable, but x2 − 5py2 = −1 may be, such as when p = 13 or 17 (of course, p needs to be with the form 4m + 1), though not when p = 41.

Numbers n for which x2 − ny2 = −1 is solvable are

- 1, 2, 5, 10, 13, 17, 26, 29, 37, 41, 50, 53, 58, 61, 65, 73, 74, 82, 85, 89, 97, 101, 106, 109, 113, 122, 125, 130, 137, 145, 149, 157, 170, 173, 181, 185, 193, 197, 202, 218, 226, 229, 233, 241, 250, ... (sequence A031396 in OEIS)

The solutions of x (for values of n in this sequence) are listed in ![]() A130226.

A130226.

These n values are divisible neither by 4 nor by a prime of the form 4m + 3, but these conditions are not sufficient --- the counterexamples are listed in ![]() A031398, the first few such ns are 34, 146, 178, 194, 205, 221, 305, 377, 386, 410, 466, 482, ... In fact, if and only if the period length of the continued fraction for

A031398, the first few such ns are 34, 146, 178, 194, 205, 221, 305, 377, 386, 410, 466, 482, ... In fact, if and only if the period length of the continued fraction for  (

(![]() A003285) is odd, then x2 − ny2 = −1 is solvable.

A003285) is odd, then x2 − ny2 = −1 is solvable.

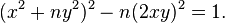

Cremona & Odoni (1989) demonstrate that the proportion of square-free n divisible by k primes of the form 4m + 1 for which the negative Pell equation is solvable is at least 40%. If it does have a solution, then it can be shown that its fundamental solution leads to the fundamental one for the positive case by squaring both sides of eq. 1,

to get,

Or, since ny2 = x2 + 1 from eq.1, then,

showing that fundamental solutions to the positive case are bigger than those for the negative case.

Transformations

I. The related equation,

(eq.2)

(eq.2)

can be used to find solutions to the positive Pell equation for certain d. Legendre proved that all primes of form d = 4m + 3 solve one case of eq.2, with the form 8m + 3 solving the negative, and 8m + 7 for the positive. Their fundamental solution then leads to the one for x2−dy2 = 1. This can be shown by squaring both sides of eq. 2,

to get,

Since  from eq.2, then,

from eq.2, then,

or simply,

showing that fundamental solutions to eq.2 are smaller than eq.1. For example, u2-3v2 = -2 is {u,v} = {1,1}, so x2 − 3y2 = 1 has {x,y} = {2,1}. On the other hand, u2 − 7v2 = 2 is {u,v} = {3,1}, so x2 − 7y2 = 1 has {x,y} = {8,3}.

II. Another related equation,

(eq.3)

(eq.3)

can also be used to find solutions to Pell equations for certain d, this time for the positive and negative case. For the following transformations,[6] if fundamental {u,v} are both odd, then it leads to fundamental {x,y}.

1. If u2 − dv2 = −4, and {x,y} = {(u2 + 3)u/2, (u2 + 1)v/2}, then x2 − dy2 = −1.

Ex. Let d = 13, then {u,v} = {3, 1} and {x,y} = {18, 5}.

2. If u2 − dv2 = 4, and {x,y} = {(u2 − 3)u/2, (u2 − 1)v/2}, then x2 − dy2 = 1.

Ex. Let d = 13, then {u,v} = {11, 3} and {x,y} = {649, 180}.

3. If u2 − dv2 = −4, and {x,y} = {(u4 + 4u2 + 1)(u2 + 2)/2, (u2 + 3)(u2 + 1)uv/2}, then x2 − dy2 = 1.

Ex. Let d = 61, then {u,v} = {39, 5} and {x,y} = {1766319049, 226153980}.

Especially for the last transformation, it can be seen how solutions to {u,v} are much smaller than {x,y}, since the latter are sextic and quintic polynomials in terms of u.

Notes

- ↑ Lettre IX. Euler à Goldbach, dated 10 August 1750 in: P. H. Fuss, ed., Correspondance Mathématique et Physique de Quelques Célèbres Géomètres du XVIIIeme Siècle … (Mathematical and physical correspondence of some famous geometers of the 18th century), vol. 1, (St. Petersburg, Russia: 1843), pp. 35-39 ; see especially page 37. From page 37: "Pro hujusmodi quaestionibus solvendis excogitavit D. Pell Anglus peculiarem methodum in Wallisii operibus expositam." (For solving such questions, the Englishman Dr. Pell devised a singular method [which is] shown in Wallis' works.)

- 1 2 3 Knorr, Wilbur R. (1976), "Archimedes and the measurement of the circle: a new interpretation", Archive for History of Exact Sciences 15 (2): 115–140, doi:10.1007/bf00348496, MR 0497462.

- 1 2 John Stillwell (2002), Mathematics and its history (2nd ed.), Springer, pp. 72–76, ISBN 978-0-387-95336-6

- ↑ "Solution d'un Problème d'Arithmétique", in J.-A. Serret (Ed.), Oeuvres de Lagrange, vol. 1, pp. 671–731, 1867.

- ↑ Prime Curios!: 313

- ↑ A Collection of Algebraic Identities: Pell Equations.

References

- Barbeau, Edward J. (2003), Pell's Equation, Problem Books in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-95529-1, MR 1949691.

- Whitford, Edward Everett (1912), The Pell equation (Phd Thesis), Columbia University

- Cremona, John E.; Odoni, R. W. K. (1989), "Some density results for negative Pell equations; an application of graph theory", Journal of the London Mathematical Society. Second Series 39 (1): 16–28, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-39.1.16, ISSN 0024-6107.

- Demeyer, Jeroen (2007), Diophantine Sets over Polynomial Rings and Hilbert’s Tenth Problem for Function Fields (PDF), Ph.D. thesis, Universiteit Gent, p. 70.

- Edwards, Harold M. (1996), Fermat's Last Theorem: A Genetic Introduction to Algebraic Number Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 50, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90230-9, MR 0616635. Originally published 1977.

- Hallgren, Sean (2007), "Polynomial-time quantum algorithms for Pell’s equation and the principal ideal problem", Journal of the ACM 54 (1): Art. No. 4, doi:10.1145/1206035.1206039..

- Lenstra, H. W., Jr. (2002), "Solving the Pell Equation" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society 49 (2): 182–192, MR 1875156..

- Pinch, R. G. E. (1988), "Simultaneous Pellian equations", Math. Proc. Cambridge Philos. Soc. 103 (1): 35–46, doi:10.1017/S0305004100064598.

- Rahn, Johann Heinrich (1668) [1659], Brancker, Thomas; Pell, eds., An introduction to algebra

- Schmidt, A.; Völlmer, U. (2005), "Polynomial time quantum algorithm for the computation of the unit group of a number field", Proc. 37th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, New York: ACM, pp. 475–480, doi:10.1145/1060590.1060661.

- Wildberger, N.J., Divine Proportions : Rational Trigonometry to Universal Geometry, Wild Egg Books, Sydney, 2005.

Further reading

- Williams, H. C. (2002). "Solving the Pell equation". In Bennett, M. A.; Berndt, B.C.; Boston, N.; Diamond, H.G.; Hildebrand, A.J.; Philipp, W. Surveys in number theory: Papers from the millennial conference on number theory. Natick, MA: A K Peters. pp. 325–363. ISBN 1-56881-162-4. Zbl 1043.11027.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Pell's equation", MathWorld.

- Pell's equation

- Pell equation solver (n has no upper limit)

- Pell equation solver (n<10^10, can also return the solution to x^2-ny^2 = +-1, +-2, +-3, and +-4)