Peano axioms

In mathematical logic, the Peano axioms, also known as the Dedekind–Peano axioms or the Peano postulates, are a set of axioms for the natural numbers presented by the 19th century Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano. These axioms have been used nearly unchanged in a number of metamathematical investigations, including research into fundamental questions of whether number theory is consistent and complete.

The need to formalize arithmetic was not well appreciated until the work of Hermann Grassmann, who showed in the 1860s that many facts in arithmetic could be derived from more basic facts about the successor operation and induction.[1] In 1881, Charles Sanders Peirce provided an axiomatization of natural-number arithmetic.[2] In 1888, Richard Dedekind proposed another axiomatization of natural-number arithmetic, and in 1889, Peano published a more precisely formulated version of them as a collection of axioms in his book, The principles of arithmetic presented by a new method (Latin: Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita).

The Peano axioms contain three types of statements. The first axiom asserts the existence of at least one member of the set of natural numbers. The next four are general statements about equality; in modern treatments these are often not taken as part of the Peano axioms, but rather as axioms of the "underlying logic".[3] The next three axioms are first-order statements about natural numbers expressing the fundamental properties of the successor operation. The ninth, final axiom is a second order statement of the principle of mathematical induction over the natural numbers. A weaker first-order system called Peano arithmetic is obtained by explicitly adding the addition and multiplication operation symbols and replacing the second-order induction axiom with a first-order axiom schema.

Formulation

When Peano formulated his axioms, the language of mathematical logic was in its infancy. The system of logical notation he created to present the axioms did not prove to be popular, although it was the genesis of the modern notation for set membership (∈, which comes from Peano's ε) and implication (⊃, which comes from Peano's reversed 'C'.) Peano maintained a clear distinction between mathematical and logical symbols, which was not yet common in mathematics; such a separation had first been introduced in the Begriffsschrift by Gottlob Frege, published in 1879.[4] Peano was unaware of Frege's work and independently recreated his logical apparatus based on the work of Boole and Schröder.[5]

The Peano axioms define the arithmetical properties of natural numbers, usually represented as a set N or  The signature (a formal language's non-logical symbols) for the axioms includes a constant symbol 0 and a unary function symbol S.

The signature (a formal language's non-logical symbols) for the axioms includes a constant symbol 0 and a unary function symbol S.

The constant 0 is assumed to be a natural number:

- 0 is a natural number.

The next four axioms describe the equality relation. Since they are logically valid in first-order logic with equality, they are not considered to be part of "the Peano axioms" in modern treatments.[6]

- For every natural number x, x = x. That is, equality is reflexive.

- For all natural numbers x and y, if x = y, then y = x. That is, equality is symmetric.

- For all natural numbers x, y and z, if x = y and y = z, then x = z. That is, equality is transitive.

- For all a and b, if b is a natural number and a = b, then a is also a natural number. That is, the natural numbers are closed under equality.

The remaining axioms define the arithmetical properties of the natural numbers. The naturals are assumed to be closed under a single-valued "successor" function S.

- For every natural number n, S(n) is a natural number.

Peano's original formulation of the axioms used 1 instead of 0 as the "first" natural number.[7] This choice is arbitrary, as axiom 1 does not endow the constant 0 with any additional properties. However, because 0 is the additive identity in arithmetic, most modern formulations of the Peano axioms start from 0. Axioms 1 and 6 define a unary representation of the natural numbers: the number 1 can be defined as S(0), 2 as S(S(0)) (which is also S(1)), and, in general, any natural number n as the result of n-fold application of S to 0, denoted as Sn(0). The next two axioms define the properties of this representation.

- For all natural numbers m and n, m = n if and only if S(m) = S(n). That is, S is an injection.

- For every natural number n, S(n) = 0 is false. That is, there is no natural number whose successor is 0.

Axioms 1, 6, 7 and 8 imply that the set of natural numbers contains the distinct elements 0, S(0), S(S(0)), and furthermore that {0, S(0), S(S(0)), …} ⊆ N. This shows that the set of natural numbers is infinite. However, to show that N = {0, S(0), S(S(0)), …}, it must be shown that N ⊆ {0, S(0), S(S(0)), …}; i.e., it must be shown that every natural number is included in {0, S(0), S(S(0)), …}. To do this however requires an additional axiom, which is sometimes called the axiom of induction. This axiom provides a method for reasoning about the set of all natural numbers.

- If K is a set such that:

- 0 is in K, and

- for every natural number n, if n is in K, then S(n) is in K,

The induction axiom is sometimes stated in the following form:

- If φ is a unary predicate such that:

- φ(0) is true, and

- for every natural number n, if φ(n) is true, then φ(S(n)) is true,

In Peano's original formulation, the induction axiom is a second-order axiom. It is now common to replace this second-order principle with a weaker first-order induction scheme. There are important differences between the second-order and first-order formulations, as discussed in the section Models below.

Arithmetic

The Peano axioms can be augmented with the operations of addition and multiplication and the usual total (linear) ordering on N. The respective functions and relations are constructed in second-order logic, and are shown to be unique using the Peano axioms.

Addition

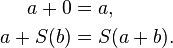

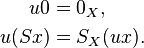

Addition is a function that maps two natural numbers (two elements of N) to another one. It is defined recursively as:

For example,

- a + 1 = a + S(0) = S(a + 0) = S(a).

The structure (N, +) is a commutative semigroup with identity element 0. (N, +) is also a cancellative magma, and thus embeddable in a group. The smallest group embedding N is the integers.

Multiplication

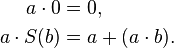

Similarly, multiplication is a function mapping two natural numbers to another one. Given addition, it is defined recursively as:

It is easy to see that setting b equal to 0 yields the multiplicative identity:

- a · 1 = a · S(0) = a + (a · 0) = a + 0 = a

Moreover, multiplication distributes over addition:

- a · (b + c) = (a · b) + (a · c).

Thus, (N, +, 0, ·, 1) is a commutative semiring.

Inequalities

The usual total order relation ≤ on natural numbers can be defined as follows, assuming 0 is a natural number:

- For all a, b ∈ N, a ≤ b if and only if there exists some c ∈ N such that a + c = b.

This relation is stable under addition and multiplication: for  , if a ≤ b, then:

, if a ≤ b, then:

- a + c ≤ b + c, and

- a · c ≤ b · c.

Thus, the structure (N, +, ·, 1, 0, ≤) is an ordered semiring; because there is no natural number between 0 and 1, it is a discrete ordered semiring.

The axiom of induction is sometimes stated in the following strong form, making use of the ≤ order:

- For any predicate φ, if

- φ(0) is true, and

- for every n, k ∈ N, if k ≤ n implies φ(k) is true, then φ(S(n)) is true,

- then for every n ∈ N, φ(n) is true.

This form of the induction axiom is a simple consequence of the standard formulation, but is often better suited for reasoning about the ≤ order. For example, to show that the naturals are well-ordered—every nonempty subset of N has a least element—one can reason as follows. Let a nonempty X ⊆ N be given and assume X has no least element.

- Because 0 is the least element of N, it must be that 0 ∉ X.

- For any n ∈ N, suppose for every k ≤ n, k ∉ X. Then S(n) ∉ X, for otherwise it would be the least element of X.

Thus, by the strong induction principle, for every n ∈ N, n ∉ X. Thus, X ∩ N = ∅, which contradicts X being a nonempty subset of N. Thus X has a least element.

First-order theory of arithmetic

All of the Peano axioms except the ninth axiom (the induction axiom) are statements in first-order logic.[10] The arithmetical operations of addition and multiplication and the order relation can also be defined using first-order axioms. The axiom of induction is second-order, since it quantifies over predicates (equivalently, sets of natural numbers rather than natural numbers), but it can be transformed into a first-order axiom schema of induction. Such a schema includes one axiom per predicate definable in the first-order language of Peano arithmetic, making it weaker than the second-order axiom.[11]

First-order axiomatizations of Peano arithmetic have an important limitation, however. In second-order logic, it is possible to define the addition and multiplication operations from the successor operation, but this cannot be done in the more restrictive setting of first-order logic. Therefore, the addition and multiplication operations are directly included in the signature of Peano arithmetic, and axioms are included that relate the three operations to each other.

The following list of axioms (along with the usual axioms of equality), which contains six of the seven axioms of Robinson arithmetic, is sufficient for this purpose:[12]

- ∀x∈N. 0 ≠ S(x)

- ∀x,y∈N. S(x) = S(y) ⇒ x = y

- ∀x∈N. x + 0 = x

- ∀x,y∈N. x + S(y) = S(x + y)

- ∀x∈N. x ⋅ 0 = 0

- ∀x,y∈N. x ⋅ S(y) = x ⋅ y + x

In addition to this list of numerical axioms, Peano arithmetic contains the induction schema, which consists of a countably infinite set of axioms. For each formula φ(x,y1,...,yk) in the language of Peano arithmetic, the first-order induction axiom for φ is the sentence

where  is an abbreviation for y1,...,yk. The first-order induction schema includes every instance of the first-order induction axiom, that is, it includes the induction axiom for every formula φ.

is an abbreviation for y1,...,yk. The first-order induction schema includes every instance of the first-order induction axiom, that is, it includes the induction axiom for every formula φ.

Equivalent axiomatizations

There are many different, but equivalent, axiomatizations of Peano arithmetic. While some axiomatizations, such as the one just described, use a signature that only has symbols for 0 and the successor, addition, and multiplications operations, other axiomatizations use the language of ordered semirings, including an additional order relation symbol. One such axiomatization begins with the following axioms that describe a discrete ordered semiring.[13]

-

.

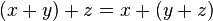

.  , i.e., addition is associative.

, i.e., addition is associative. -

.

.  , i.e., addition is commutative.

, i.e., addition is commutative. -

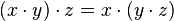

.

.  , i.e., multiplication is associative.

, i.e., multiplication is associative. -

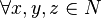

.

.  , i.e., multiplication is commutative.

, i.e., multiplication is commutative. -

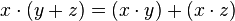

.

.  , i.e., the distributive law.

, i.e., the distributive law. -

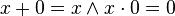

.

.  , i.e., zero is the identity element for addition.

, i.e., zero is the identity element for addition. -

.

.  , i.e., one is the identity element for multiplication.

, i.e., one is the identity element for multiplication. -

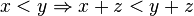

.

.  , i.e., the '<' operator is transitive.

, i.e., the '<' operator is transitive. -

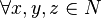

.

.  , i.e., the '<' operator is irreflexive.

, i.e., the '<' operator is irreflexive. -

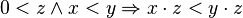

.

.  .

. -

.

.  .

. -

.

.  .

. -

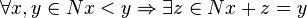

.

. -

.

.  .

. -

.

.  .

.

The theory defined by these axioms is known as PA−; PA is obtained by adding the first-order induction schema.

An important property of PA− is that any structure M satisfying this theory has an initial segment (ordered by ≤) isomorphic to N. Elements of M \ N are known as nonstandard elements.

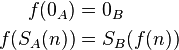

Models

A model of the Peano axioms is a triple (N, 0, S), where N is a (necessarily infinite) set, 0 ∈ N and S : N → N satisfies the axioms above. Dedekind proved in his 1888 book, What are numbers and what should they be (German: Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen) that any two models of the Peano axioms (including the second-order induction axiom) are isomorphic. In particular, given two models (NA, 0A, SA) and (NB, 0B, SB) of the Peano axioms, there is a unique homomorphism f : NA → NB satisfying

and it is a bijection. This means that second-order Peano axioms are categorical. This is not the case with any first-order reformulation of the Peano axioms, however.

Nonstandard models

Although the usual natural numbers satisfy the axioms of PA, there are other non-standard models as well; the compactness theorem implies that the existence of nonstandard elements cannot be excluded in first-order logic. The upward Löwenheim–Skolem theorem shows that there are nonstandard models of PA of all infinite cardinalities. This is not the case for the original (second-order) Peano axioms, which have only one model, up to isomorphism. This illustrates one way the first-order system PA is weaker than the second-order Peano axioms.

When interpreted as a proof within a first-order set theory, such as ZFC, Dedekind's categoricity proof for PA shows that each model of set theory has a unique model of the Peano axioms, up to isomorphism, that embeds as an initial segment of all other models of PA contained within that model of set theory. In the standard model of set theory, this smallest model of PA is the standard model of PA; however, in a nonstandard model of set theory, it may be a nonstandard model of PA. This situation cannot be avoided with any first-order formalization of set theory.

It is natural to ask whether a countable nonstandard model can be explicitly constructed. The answer is affirmative as Skolem in 1933 provided an explicit construction of such a nonstandard model. On the other hand, Tennenbaum's theorem, proved in 1959, shows that there is no countable nonstandard model of PA in which either the addition or multiplication operation is computable.[14] This result shows it is difficult to be completely explicit in describing the addition and multiplication operations of a countable nonstandard model of PA. However, there is only one possible order type of a countable nonstandard model. Letting ω be the order type of the natural numbers, ζ be the order type of the integers, and η be the order type of the rationals, the order type of any countable nonstandard model of PA is ω + ζ·η, which can be visualized as a copy of the natural numbers followed by a dense linear ordering of copies of the integers.

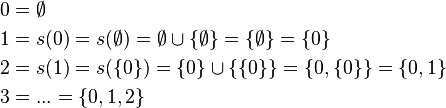

Set-theoretic models

The Peano axioms can be derived from set theoretic constructions of the natural numbers and axioms of set theory such as the ZF.[15] The standard construction of the naturals, due to John von Neumann, starts from a definition of 0 as the empty set, ∅, and an operator s on sets defined as:

- s(a) = a ∪ { a }.

The set of natural numbers N is defined as the intersection of all sets closed under s that contain the empty set. Each natural number is equal (as a set) to the set of natural numbers less than it:

and so on. The set N together with 0 and the successor function s : N → N satisfies the Peano axioms.

Peano arithmetic is equiconsistent with several weak systems of set theory.[16] One such system is ZFC with the axiom of infinity replaced by its negation. Another such system consists of general set theory (extensionality, existence of the empty set, and the axiom of adjunction), augmented by an axiom schema stating that a property that holds for the empty set and holds of an adjunction whenever it holds of the adjunct must hold for all sets.

Interpretation in category theory

The Peano axioms can also be understood using category theory. Let C be a category with terminal object 1C, and define the category of pointed unary systems, US1(C) as follows:

- The objects of US1(C) are triples (X, 0X, SX) where X is an object of C, and 0X : 1C → X and SX : X → X are C-morphisms.

- A morphism φ : (X, 0X, SX) → (Y, 0Y, SY) is a C-morphism φ : X → Y with φ 0X = 0Y and φ SX = SY φ.

Then C is said to satisfy the Dedekind–Peano axioms if US1(C) has an initial object; this initial object is known as a natural number object in C. If (N, 0, S) is this initial object, and (X, 0X, SX) is any other object, then the unique map u : (N, 0, S) → (X, 0X, SX) is such that

This is precisely the recursive definition of 0X and SX.

Consistency

When the Peano axioms were first proposed, Bertrand Russell and others agreed that these axioms implicitly defined what we mean by a "natural number". Henri Poincaré was more cautious, saying they only defined natural numbers if they were consistent; if there is a proof that starts from just these axioms and derives a contradiction such as 0 = 1, then the axioms are inconsistent, and don't define anything. In 1900, David Hilbert posed the problem of proving their consistency using only finitistic methods as the second of his twenty-three problems.[17] In 1931, Kurt Gödel proved his second incompleteness theorem, which shows that such a consistency proof cannot be formalized within Peano arithmetic itself.[18]

Although it is widely claimed that Gödel's theorem rules out the possibility of a finitistic consistency proof for Peano arithmetic, this depends on exactly what one means by a finitistic proof. Gödel himself pointed out the possibility of giving a finitistic consistency proof of Peano arithmetic or stronger systems by using finitistic methods that are not formalizable in Peano arithmetic, and in 1958, Gödel published a method for proving the consistency of arithmetic using type theory.[19] In 1936, Gerhard Gentzen gave a proof of the consistency of Peano's axioms, using transfinite induction up to an ordinal called ε0.[20] Gentzen explained: "The aim of the present paper is to prove the consistency of elementary number theory or, rather, to reduce the question of consistency to certain fundamental principles". Gentzen's proof is arguably finitistic, since the transfinite ordinal ε0 can be encoded in terms of finite objects (for example, as a Turing machine describing a suitable order on the integers, or more abstractly as consisting of the finite trees, suitably linearly ordered). Whether or not Gentzen's proof meets the requirements Hilbert envisioned is unclear: there is no generally accepted definition of exactly what is meant by a finitistic proof, and Hilbert himself never gave a precise definition.

The vast majority of contemporary mathematicians believe that Peano's axioms are consistent, relying either on intuition or the acceptance of a consistency proof such as Gentzen's proof. The small number of mathematicians who advocate ultrafinitism reject Peano's axioms because the axioms require an infinite set of natural numbers.

See also

- Foundations of mathematics

- Gentzen's consistency proof

- Goodstein's theorem

- Paris–Harrington theorem

- Presburger arithmetic

- Robinson arithmetic

- Second-order arithmetic

- Non-standard model of arithmetic

- Set-theoretic definition of natural numbers

- Frege's theorem

Footnotes

- ↑ Grassmann 1861

- ↑ Peirce 1881; also see Shields 1997

- ↑ van Heijenoort 1967:94

- ↑ Van Heijenoort 1967, p. 2

- ↑ Van Heijenoort 1967, p. 83

- ↑ Van Heijenoort 1967, p. 83

- ↑ Peano 1889, p. 1

- ↑ Note: The non-contiguous set satisfies axiom 1 as it has a 0 element, 2-5 as it doesn't affect equality relations, 6 & 8 as all pieces have a successor, bar the zero element and axiom 7 as no two dominos topple, or are toppled by, the same piece.

- ↑ Note: Though the ring of dark pieces would itself satisfy axiom 9, it wouldn't satisfy axiom 8, as its zero element would have a predecessor.

- ↑ Partee et al. 2012:215

- ↑ Harsanyi 1983.

- ↑ Mendelson 1997:155

- ↑ Kaye 1991, pp. 16–18

- ↑ Kaye 1991, sec. 11.3

- ↑ Suppes 1960; Hatcher 1982

- ↑ Tarski & Givant 1987, sec. 7.6

- ↑ Hilbert 1900

- ↑ Godel 1931

- ↑ Godel 1958

- ↑ Gentzen 1936

References

- Martin Davis, 1974. Computability. Notes by Barry Jacobs. Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York University.

- Richard Dedekind (1888). Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen? (What are and what should the numbers be?) (PDF). Vieweg. Retrieved 31 October 2013.. Two English translations:

- 1963 (1901). Essays on the Theory of Numbers. Beman, W. W., ed. and trans. Dover.

- 1996. In From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics, 2 vols, Ewald, William B., ed. Oxford University Press: 787–832.

- Gentzen, G., 1936, Die Widerspruchsfreiheit der reinen Zahlentheorie. Mathematische Annalen 112: 132–213. Reprinted in English translation in his 1969 Collected works, M. E. Szabo, ed. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Kurt Gödel (1931). "Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme, I" (PDF). Monatshefte für Mathematik 38: 173–198. doi:10.1007/bf01700692.. See On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems for details on English translations.

- --------, 1958, "Über eine bisher noch nicht benützte Erweiterung des finiten Standpunktes," Dialectica 12: 280–87. Reprinted in English translation in 1990. Gödel's Collected Works, Vol II. Solomon Feferman et al., eds. Oxford University Press.

- Hermann Grassmann (1861). Lehrbuch der Arithmetik (A tutorial in arithmetic) (PDF). Enslin.

- Hatcher, William S., 1982. The Logical Foundations of Mathematics. Pergamon. Derives the Peano axioms (called S) from several axiomatic set theories and from category theory.

- David Hilbert,1901, "Mathematische Probleme". Archiv der Mathematik und Physik 3(1): 44–63, 213–37. English translation by Maby Winton, 1902, "Mathematical Problems," Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 8: 437–79.

- Kaye, Richard, 1991. Models of Peano arithmetic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853213-X.

- Mendelson, Elliott, 1997. Introduction to Mathematical Logic, 4th ed. Chapman & Hall.

- Peirce, C. S. (1881). "On the Logic of Number". American Journal of Mathematics 4 (1–4). pp. 85–95. doi:10.2307/2369151. JSTOR 2369151. MR 1507856. Reprinted (CP 3.252-88), (W 4:299-309).

- Paul Shields. (1997), "Peirce's Axiomatization of Arithmetic", in Houser et al., eds., Studies in the Logic of Charles S. Peirce.

- Patrick Suppes, 1972 (1960). Axiomatic Set Theory. Dover. ISBN 0-486-61630-4. Derives the Peano axioms from ZFC.

- Alfred Tarski, and Givant, Steven, 1987. A Formalization of Set Theory without Variables. AMS Colloquium Publications, vol. 41.

- Edmund Landau, 1965 Grundlagen Der Analysis. AMS Chelsea Publishing. Derives the basic number systems from the Peano axioms. English/German vocabulary included. ISBN 978-0-8284-0141-8

- Partee, Barbara; Ter Meulen, Alice; Wall, Robert (2012). Mathematical Methods in Linguistics. Springer.

- Harsanyi, John C. (1983). "Mathematics, the empirical facts and logical necessity". Erkenntniss 19: 167 ff.

- van Heijenoort, Jean, ed. (1976) [1967]. From Frege to Godel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879–1931 (3rd printing with corrections, 3rd ed.). Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-32449-8. Contains translations of the following two papers, with valuable commentary:

- Richard Dedekind, 1890, "Letter to Keferstein." pp. 98–103. On p. 100, he restates and defends his axioms of 1888.

- Giuseppe Peano, 1889. Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita (The principles of arithmetic, presented by a new method), pp. 83–97. An excerpt of the treatise where Peano first presented his axioms, and recursively defined arithmetical operations.

This article incorporates material from PA on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

External links

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Henri Poincaré" by Mauro Murzi. Includes a discussion of Poincaré's critique of the Peano's axioms.

- First-order arithmetic, a chapter of a book on the incompleteness theorems by Karl Podnieks.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Peano axioms", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Peano arithmetic at PlanetMath.org.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Peano's Axioms", MathWorld.

- What are numbers, and what is their meaning?: Dedekind commentary on Dedekind's work, Stanley N. Burris, 2001.