Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (French: Pays des Illinois) — sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (French: la Haute-Louisiane; Spanish: Alta Luisiana) — was a region in what is now the Midwestern United States. The terms generally referred to the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, though settlement was concentrated in what is now the U.S. state of Illinois, with outposts in Missouri and Indiana. Explored in 1673 from Green Bay to the Arkansas River by the Canadien expedition of Louis Joliet and Jacques Marquette, the area was claimed by France.

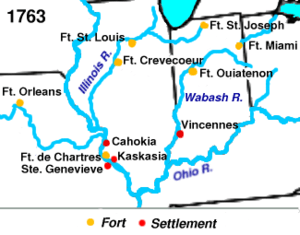

Up until 1717, the Illinois Country was governed by the French province of Canada, but by order of King Louis XV, the Illinois Country was annexed to the French province of Louisiana, with the northeastern border being on or near the Illinois River.[1] The territory thus became known as "Upper Louisiana." By the mid-18th century, the major settlements included Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Chartres, Saint Philippe, and Prairie du Rocher, all on the east side of the Mississippi in present-day Illinois; and Ste. Genevieve across the river in Missouri, as well as Fort Vincennes in what is now Indiana.[2]

As a consequence of the French defeat in the Seven Years' War, the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River was ceded to the British, and the land west of the river to the Spanish. Following the British occupation of the left bank (when heading downstream) of the Mississippi in 1764, some Canadien settlers remained in the area, while others crossed the river, forming new settlements such as St. Louis.

Eventually, the eastern part of the Illinois Country became part of the British Province of Quebec, while the inhabitants chose to side with the Americans during the revolt of the thirteen colonies. Although the lands west of the Mississippi were sold in 1803 to the United States by France—which had reclaimed possession of Luisiana from the Spanish in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso—French language and culture continued to exist in the area, with the Missouri French dialect still being spoken into the 20th century.[2]

Because of the deforestation that resulted from the cutting of much wood for fuel during the 19th-century age of steamboats, the Mississippi River became more shallow and broad, with more severe flooding and lateral changes in its channel in the stretch from St. Louis to the confluence with the Ohio River. As a consequence, many architectural and archaeological resources were lost to flooding and destruction of early French colonial villages originally located near the river, including Kaskaskia, St. Philippe, Cahokia, and Ste. Genevieve.[3]

Location and boundaries

The boundaries of the Illinois Country were defined in a variety of ways, but the region now known as the American Bottom was nearly at the center of all descriptions. One of the earliest known geographic features designated as Ilinois was what later became known as Lake Michigan, on a map prepared in 1671 by French Jesuits. Early French missionaries and traders referred to the area southwest and southeast of the lake, including much of the upper Mississippi Valley, by this name. Illinois was also the name given to an area inhabited by the Illiniwek. A map of 1685 labels a large area southwest of the lake les Ilinois; in 1688, the Italian cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli labeled the region (in Italian) as Illinois country. In 1721, the seventh civil and military district of Louisiana was named Illinois. It included more than half of the present state, as well as the land between the Arkansas River and the line of 43 degrees north latitude, and the country between the Rocky Mountains and the Mississippi River. A royal ordinance of 1722—following the transfer of the Illinois Country's governance from Canada to Louisiana—may have featured the broadest definition of the region: all land claimed by France south of the Great Lakes and north of the mouth of the Ohio River, which would include the lower Missouri Valley as well as both banks of the Mississippi.[1]

A generation later, trade conflicts between Canada and Louisiana led to a more defined boundary between the French colonies; in 1745, Louisiana governor general Vaudreuil set the northeastern bounds of his domain as the Wabash valley up to the mouth of the Vermilion River (near present-day Danville, Illinois); from there, northwest to le Rocher on the Illinois River, and from there west to the mouth of the Rock River (at present day Rock Island, Illinois).[1] Thus, Vincennes and Peoria were the limit of Louisiana'a reach; the outposts at Ouiatenon (on the upper Wabash near present-day Lafayette, Indiana), Chicago, Fort Miamis (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana) and Prairie du Chien operated as dependencies of Canada.[1]

This boundary between Canada and the Illinois Country remained in effect until the Treaty of Paris in 1763, after which France surrendered its remaining territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain. (Although British forces had occupied the "Canadian" posts in the Illinois and Wabash countries in 1761, they did not occupy Vincennes or the Mississippi River settlements at Cahokia and Kaskaskia until 1764, after the ratification of the peace treaty.[4]) As part of a general report on conditions in the newly conquered lands, Gen. Thomas Gage, then commandant at Montreal, explained in 1762 that, although the boundary between Louisiana and Canada wasn't exact, it was understood the upper Mississippi above the mouth of the Illinois was in Canadian trading territory.[5]

Distinctions became somewhat clearer after the Treaty of Paris in 1763, when Britain acquired Canada and the land claimed by France east of the Mississippi and Spain acquired Louisiana west of the Mississippi. Many French settlers moved west across the river to escape British control.[6] On the west bank, the Spanish also continued to refer to the western region governed from St. Louis as the District of Illinois and referred to St. Louis as the city of Illinois.[1]

Exploration and settlement

The first French explorations of the Illinois Country were in the first half of the 17th century, led by explorers and missionaries based in Canada. Étienne Brûlé explored the upper Illinois country in 1615 but did not document his experiences. Joseph de La Roche Daillon reached an oil spring at the northeasternmost fringe of the Mississippi River basin during his 1627 missionary journey.

In 1669-70, Father Jacques Marquette, a missionary in French Canada, was at a mission station on Lake Superior, when he met native traders from the Illinois Confederation. He learned about the great river that ran through their country to the south and west. In 1673-74, with a commission from the Canadian government, Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi River territory from Green Bay to the Arkansas River, including the Illinois River valley. In 1675, Marquette returned to found a Jesuit mission at the Grand Village of the Illinois. Over the next decades missions, trade posts, and forts were established in the region.[7][8] By 1714, the principal European, non-native inhabitants were Canadien fur traders, missionaries and soldiers, dealing with Native Americans, particularly the group known as the Kaskaskia. The main French settlements were established at Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Sainte Genevieve. By 1752, the population had risen to 2,573.[9]

Fort St. Louis du Rocher

French explorers led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle built Fort St. Louis on a large butte by the Illinois River in the winter of 1682.[10] Called La Rocher, the butte provided an advantageous position for the fort above the river.[10] A wooden palisade was the only form of defenses that La Salle used in securing the site. Inside the fort were a few wooden houses and native shelters. The French intended St. Louis to be the first of several forts to defend against English incursions and keep their settlements confined to the East Coast. Accompanying the French to the region were allied members of several native tribes from eastern areas, who integrated with the Kaskaskia: the Miami, Shawnee, and Mahican. The tribes established a new settlement at the base of the butte known as Hotel Plaza. After La Salle's five-year monopoly ended New France governor Joseph-Antoine de La Barre wished to put Fort Saint Louis along with Fort Frontenac under his jurisdiction.[11] By orders of the governor, traders and his officer were escorted to Illinois.[11] On August 11, 1683, LaSalle's armorer, Pierre Prudhomme, obtained approximately one and three-quarters of a mile of the north portage shore.[11]

During the earliest of the French and Indian Wars, the French used the fort as a refuge against attacks by Iroquois, who were allied with the British. The Iroquois forced the settlers, then commanded by Henri de Tonti, to abandon the fort in 1691. De Tonti reorganized the settlers at Fort Pimitoui in modern-day Peoria.

French troops commanded by Pierre Deliette may have occupied Fort St. Louis from 1714 to 1718; Deliette's jurisdiction over the region ended when the territory was transferred from Canada to Louisiana. Fur trappers and traders used the fort periodically in the early 18th century until it became too dilapidated. No surface remains of the fort are found at the site today. The region was periodically occupied by a variety of native tribes who were forced westward by the expansion of European settlements. These included the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Ojibwe.

On April 20, 1769, an Illinois Confederation warrior assassinated Chief Pontiac while he was on a diplomatic mission in Cahokia. According to local legend, the Ottawa, along with their allies the Potawatomi, attacked a band of Illini along the Illinois River. The tribe climbed to the butte to seek refuge from the attack. The Ottawa and Potawatomi continued the siege until the Illini tribe starved to death. After hearing the story, Europeans referred to the butte as Starved Rock.

Fort de Chartres

On January 1, 1718, a trade monopoly was granted to John Law and his Company of the West (which was to become the Company of the Indies in 1719). Hoping to make a fortune mining precious metals in the area, the company with a military contingent sent from New Orleans built a fort to protect its interests. Construction began on the first Fort de Chartres (in present-day Illinois) in 1718 and was completed in 1720.

The original fort was located on the east bank of the Mississippi River, downriver (south) from Cahokia and upriver of Kaskaskia. The nearby settlement of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois, was founded by French-Canadian colonists in 1722, a few miles inland from the fort.

The fort was to be the seat of government for the Illinois Country and help to control the aggressive Fox Indians. The fort was named after Louis, duc de Chartres, son of the regent of France. Because of frequent flooding, another fort was built further inland in 1725. By 1731, the Company of the Indies had gone defunct and turned Louisiana and its government back to the king. The garrison at the fort was removed to Kaskaskia, Illinois in 1747, about 18 miles to the south. A new stone fort was planned near the old fort and was described as "nearly complete" in 1754, although construction continued until 1760.

The new stone fort was headquarters for the French Illinois Country for less than 20 years, as it was turned over to the British in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris at the end of the French and Indian War. The British Crown declared almost all the land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River from Florida to Newfoundland a Native American territory called the Indian Reserve following the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The government ordered settlers to leave or get a special license to remain. This and the desire to live in a Catholic territory caused many of the Canadiens to cross the Mississippi to live in St. Louis or Ste. Genevieve.

The British took control of Fort de Chartres on October 10, 1765 and renamed it Fort Cavendish. The British softened the initial expulsion order and offered the Canadien inhabitants the same rights and privileges enjoyed under French rule. In September 1768, the British established a Court of Justice, the first court of common law in the Mississippi Valley (the French law system is called civil law).

After severe flooding in 1772, the British saw little value in maintaining the fort and abandoned it. They moved the military garrison to the fort at Kaskaskia and renamed it Fort Gage. Chartres' ruined but intact magazine is considered the oldest surviving European structure in Illinois and was reconstructed in the 20th century, with much of the rest of the Fort.

Agricultural settlement

According to historian, Carl J. Ekberg, the French settlement pattern in Illinois Country was generally unique in 17th- and 18th-century French North America. These were unlike other such French settlements, which primarily had been organized in separated homesteads along a river with long rectangular plots stretching back from the river (ribbon plots). The Illinois Country French, although they marked long-ribbon plots, did not reside on them. Instead, settlers resided together in farming villages, more like the farming villages of northern France, and practiced communal agriculture.[12]

After the port of New Orleans, along the Mississippi River to the south, was founded in 1718, more African slaves were imported to the Illinois Country for use as agricultural and mining laborers. By the mid-eighteenth century, slaves accounted for as high as a third of the population.[13]

Other settlements

- In 1675, Jacques Marquette founded the mission of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin at the Grand Village of the Illinois, near present Utica, Illinois, which was destroyed by Iroquois in 1680.[7][8]

- Peoria was at first the southernmost part of New France, then the northernmost part of the French Colony of Louisiana, and finally the westernmost part of the newly formed United States. Fort Crevecoeur was first founded in 1680. Another fort, often called Fort Pimiteoui, and later Old Fort Peoria, was established in 1691.[14] French interests dominated at Peoria for well over a hundred years, from the time the first French explorers came up the Illinois River in 1673 until the first United States settlers began to move into the area around 1815. A small French presence persisted for a time on the east bank of the river, but was gone by about 1846. Today, only faint echoes of French Peoria survive in the street plan of downtown Peoria, and in the name of an occasional street, school, or hotel meeting room: Joliet, Marquette, LaSalle.

- The Mission of the Guardian Angel was established near the Chicago portage between 1696-1700.

- Cahokia, established in 1699 by French missionaries from Quebec, was one of the earliest permanent settlements in the region. It became one of the most populous of the northern towns. In 1787, it was made the seat of St. Clair County in the Northwest Territory. In 1801, William Henry Harrison, then governor of Indiana Territory, enlarged St. Clair County to administer a vast area extending to the Canadian border. By 1814, the county had been reduced to almost the size of the present St. Clair County, Illinois. The county seat was shifted from Cahokia to Belleville. On April 20, 1769, the great Indian leader Chief Pontiac was murdered in Cahokia by a chief of the Peoria.

- Kaskaskia, established in 1703, was at first a tiny mission station. It later flourished to become capital of the Illinois Territory, 1809–1818, and the first capital of the state of Illinois, 1818-1820. The French built a fort here in 1721, which was destroyed in 1763 by the British. (The fort was situated above what was then the lower course of the Kaskaskia River, but became the new channel of the Mississippi in 1881.) During the American Revolution, General George Rogers Clark took possession of the village in 1778. The residents rang the church bell in celebration, and it became known as the "liberty bell". (It had been sent in 1741 by King Louis XV.) Flooding and a lateral shift of the river channel in 1881 cut off the old settlement from the mainland of Illinois and destroyed some of the village and its archaeology. Much of the village cemetery was transferred to the higher ground of Fort Kaskaskia State Park across the river. Today visitors can reach the remnants of Kaskaskia only by a bridge and road from the Missouri side. In the Great Flood of 1993, the Mississippi submerged all but a few rooftops and the steeple of the Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception, built in 1843 and moved brick by brick to the new location on Kaskaskia Island about 1893.

- In 1720, Philip Francois Renault, the Director of Mining Operations for the Company of the West, arrived with about 200 laborers and mechanics and 500 African slaves from Santo Domingo to work the mines. However, the mines yielded only unprofitable coal and lead, providing insufficient revenues for the Company of the West to survive. In 1723, Renault, with his workers and slaves, established the village St. Philippe (on the Bottoms down from the present-day unincorporated community of Renault, Illinois in Monroe County, Illinois.) It was about 3 miles north of Fort de Chartres. This is the first record of African slaves in the region. Some of the French farmers also used slaves for labor, but most families held only a few, if any. The village quickly produced an agricultural surplus, with its goods sold to lower Louisiana, as well as to settlements less successful than those in the Illinois Country, such as Arkansas Post.

- The original Ste. Genevieve was established around 1750 along the western banks of the Mississippi River. The village consisted mostly farmers and merchants of French-Canadian descent from the settlements on the east side. Despite flooding, the town remained in that location until the great flood of 1785 destroyed much property. The villagers decided to move the entire village to higher ground about two miles north and half a mile back from the river floodplain. The city has retained the most buildings of French Colonial architecture in the US.

- The French established Fort Orleans in 1723 along the Missouri River near Brunswick, Missouri.

- Fort Vincennes, later known as St. Vinennes and eventually Vincennes, Indiana, was established in 1732. The British renamed it Fort Sackville after their capture in the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War.) George Rogers Clark renamed it Fort Patrick Henry, for the Governor of Virginia, when he took it in the American Revolution. Although part of the original expansive Illinois Country, as part of the Northwest Territory, it became the seat of a separate county.

- The French built Fort Massac on the Ohio River in 1757 near the present Metropolis, Illinois.

- Saint Louis, Missouri was founded in 1764 by French fur traders. In 1765, St. Louis was made the capital of French Upper Louisiana, and after 1767, control of the western Mississippi region was given to the Spanish. In 1780, St. Louis was attacked by British forces, mostly Native Americans, during the American Revolutionary War.[15]

Illinois Country under American control

During the Revolutionary War, General George Rogers Clark took possession of the part of the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi for Virginia. In November 1778, the Virginia legislature created the county of Illinois, comprising all of the lands lying west of the Ohio River to which Virginia had any claim, with Kaskaskia as the county seat. Captain John Todd was named as governor. However, this government was limited to the former Canadien settlements and was rather ineffective.

For their assistance to General Clark in the war, settled Canadien and Indian residents of Illinois Country were given full citizenship. Under the Northwest Ordinance and many subsequent treaties and acts of Congress, the Canadien and Indian residents of Vincennes and Kaskaskia were granted specific exemptions, as they had declared themselves citizens of Virginia. The term Illinois Country was sometimes used in legislation to refer to these settlements.

Much of the Illinois Country region became an organized territory of the United States with the establishment of the Northwest Territory in 1787. In 1803, the old Illinois Country area west of the Mississippi was gained by the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase.

Flooding

During the 19th century, steamboat travel flourished on the Mississippi River, which grew the economy of St. Louis and other towns, but simultaneously led to deforestation along the river. Adverse environmental effects resulted, including more severe flooding as the river became broader and more shallow, lateral changes in the channel, instability of banks, and loss of towns due to flooding or channel changes. Much of archeological importance was lost in the flooding and destruction of French colonial towns such as Kaskaskia, St. Philippe, Cahokia, Illinois, and old Ste. Genevieve, Missouri.

See also

- Historic regions of the United States

- Missouri French, a dialect of the French language spoken by 1,000 people in remnants of Old France in Missouri

- New France

- Ohio Country

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ekberg, Carl (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. Urbana and Chicago, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780252069246. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- 1 2 Carrière, J. -M. (1939). "Creole Dialect of Missouri". American Speech (Duke University Press) 12 (6): 502–503. JSTOR 451217.

- ↑ Norris, F. Terry (1997). "Where Did the Villages Go? Steamboats, Deforestation, and Archaeological Loss in the Mississippi Valley". In Hurley, Andrew. Common Fields: An Environmental History of St. Louis. Missouri History Museum. pp. 73–89. ISBN 978-1-883982-15-7.

- ↑ Hamelle, W.H. (1915). A Standard History of White County, Indiana. Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing Co. p. 12. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ Shortt, Adam; Doughty, Arthur G., eds. (1907). Documents Relating to the Constitutional History of Canada, 1759-1791. Ottawa: Public Archives Canada. p. 72. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ Carrière, J. -M. (1939). "Creole Dialect of Missouri". American Speech (Duke University Press) 12 (6): 502–503. JSTOR 451217.

- 1 2 Native Americans-Historic:The Illinois-Society, The French Illinois State Museum

- 1 2 Jacques Marquette 1673 | Virtual Museum of New France Canadian Museum of History

- ↑ Guy Frégault, Le Grand Marquis: Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil et la Louisiane (Montreal, 1952), pp. 129–130

- 1 2 "The Illinois Archaeology - Starved Rock Site", Museum Link - Illinois State Museum, 2000, accessed June 15, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Skinner, Claiborne A. The Upper Country: French Enterprise in the Colonial Great Lakes. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2008. Print.

- ↑ Ekberg (2000), p. 28-32

- ↑ Ekberg (2000), p. 2-3

- ↑ The First European Settlement in Illinois

- ↑ Usgennet.org Attack On St. Louis: May 26, 1780.

References

- French Peoria in the Illinois Country, 1673-1846 Library of Congress exhibit

- Louisiana Digital Libraries Plan for Fort Orleans

Bibliography

- Alvord, Clarence W. and Sutton, Robert M., The Illinois Country, 1673–1818, ISBN 0-252-01337-9

- Belting, Natalia Maree, Kaskaskia under the French Regime by ISBN 0-8093-2536-5

- Brackenridge, Henri Marie, Recollections of Persons and Places in the West (Google Books)

- Ekberg, Carl J., Stealing Indian Women: Native Slavery in the Illinois Country, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

- Ekberg, Carl J., Francois Vallé and His World: Upper Louisiana Before Lewis and Clark, Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002.

- Ekberg, Carl J., French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000, ISBN 0-252-06924-2

- Ekberg, Carl J., Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier, Tucson, AZ: Patrice Press, 1996, ISBN 1-880397-14-5

External links

- Lenville J. Stelle, Inoca Ethnohistory Project: Eye Witness Descriptions of the Contact Generation, 1667 - 1700

- Foundation for Restoration of Ste. Genevieve, Inc. Guibourd Historic House & Mecker Research Library

- Ste. Genevieve County Historical and Genealogical Resources

- Felix Vallé State Historic Site Missouri Department of Natural Resources

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||