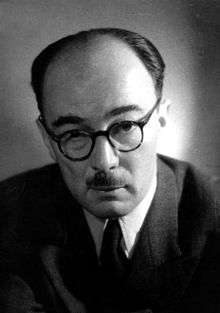

Paweł Jasienica

| Paweł Jasienica | |

|---|---|

Paweł Jasienica | |

| Born |

Leon Lech Beynar 10 November 1909 Simbirsk, Russia |

| Died |

19 August 1970 (aged 60) Warsaw, Poland |

| Resting place | Powązki Cemetery |

| Occupation | writer, historian |

| Language | Polish |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Ethnicity | Polish |

| Citizenship | Polish |

| Alma mater | Stefan Batory University |

| Genre | history |

| Subject | Polish history |

| Notable works | Piast Poland, Jagiellonian Poland, The Commonwealth of Both Nations |

Paweł Jasienica was the pen name of Leon Lech Beynar (10 November 1909 – 19 August 1970), a Polish historian, journalist and soldier.

During World War II, Jasienica (then, Leon Beynar) fought in the Polish Army, and later, the Armia Krajowa resistance. Near the end of the war, he was also working with the anti-Soviet resistance, which later led to him taking up a new name, Paweł Jasienica, to hide from the communist government of the People's Republic of Poland. He was associated with the Tygodnik Powszechny weekly and several other newspapers and magazines. He is best known for his 1960s books on Polish history—on the Kingdom of Poland under the Piast Dynasty, the Jagiellon Dynasty, and the elected kings of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Those books, still popular, played an important role in popularizing Polish history among several generations of readers.

Jasienica became an outspoken critic of the censorship in the People's Republic of Poland, and as a notable dissident, he was persecuted by the government. He was subject to significant invigilation by the security services, and his second wife was in fact an agent of the communist secret police. For a brief period marking the end of his life, his books were prohibited from being distributed or printed.

Life

Youth

Beynar was born on 10 November 1909 in Simbirsk, Russia,[1] to Polish parents, Mikołaj Beynar and Helena Maliszewska. His paternal grandfather, Ludwik Beynar, fought in the January Uprising and married a Spanish woman, Joanna Adela Feugas.[2] His maternal grandfather, Wiktor Maliszewski, fought in the November Uprising.[2] Both of his grandfathers eventually settled in the Russian Empire.[2] His father, Mikołaj, worked as an agronomist.[2] Beynar's family lived in Russia and Ukraine—they moved from Simbirsk to a location near Bila Tserkva and Uman, then to Kiev until the Russian Revolution of 1917, after which they decided to settle in the independent Poland.[3] After brief stay in Warsaw, during the Polish–Soviet War, his family settled in Opatów, and in 1924, moved to Grodno.[2]

Beynar graduated from gymnasium (secondary school) in Wilno (Vilnius) and graduated in history from Stefan Batory University in Wilno (his thesis concerned the January Uprising).[1][2][4] At the university he was an active member of several organizations including Klub Intelektualistów (Intellectuals' Club) and Akademicki Klub Włóczęgów (Academic Club of Vagabonds). After graduating, he finished training for the officer cadet (podchorąży) in the Polish Army.[2] From 1928 to 1937 he lived in Grodno, where he worked as a history teacher in a gymnasium; later he was employed as an announcer for Polish Radio Wilno.[1][2][3] Here also, Beynar embarked on his career as author and essayist, writing for a local newspaper, Słowo Wileńskie (The Wilno Word).[1] On 11 November 1934 he marred Władysława Adamowicz, and in 1938 his daughter Ewa was born.[2] In 1935 he published his first history book - about king Zygmunt August, Zygmunt August na ziemiach dawnego Wielkiego Księstwa (Sigismund Augustus on the Lands of the Former Grand Duchy [of Lithuania]).[1]

World War II

During World War II, Beynar was a soldier in the Polish Army, fighting the German Wehrmacht when it invaded Poland in September 1939.[1][3] He commanded a platoon near Sandomierz and was eventually taken prisoner by the Germans.[2] While in a temporary prisoner-of-war camp in Opatów, he was able to escape with the help of some old school friends from the time his family lived there in the early 1920s.[2] He joined the Polish underground organization, "Związek Walki Zbrojnej" (Association for Armed Combat), later transformed into the "Armia Krajowa" ("AK"; the Home Army), and continued the fight against the Germans.[1][3][4][5] In the resistance he had the rank of lieutenant, worked in the local Wilno headquarters and was an editor of an underground newspaper "Pobudka".[2][3] He was also involved in the underground teaching.[2] In July 1944 he took part in the operation aimed at the liberation of Wilno from the Germans (Operation Ostra Brama). In the wake of this operation, around 19–21 August, his partisan unit, like many others, was intercepted and attacked by the Soviets. He was taken prisoner; sources vary as to whether he was to be exiled to Siberia or conscripted into the Polish People's Army. Either way he escaped and rejoined AK partisans (the Home Army 5th Wilno Brigade).[3][5][6] For a while, he was an aide to Major Zygmunt Szendzielarz (Łupaszko) and was member of the anti-Soviet resistance, Wolność i Niezawisłość (WiN, Freedom and Independence). He was promoted to the rank of captain.[1][3][4][5] Wounded in August 1945, he left the Brigade before it was destroyed by the Soviets, and avoided the fate of most of its officers who were sentenced to death.[5][6] While recovering from his wounds, he found shelter in the village of Jasienica.[1][6]

Post-war

After recovering from his wounds in 1945, Beynar decided to leave the resistance, and instead began publishing in an independent Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny.[1][3][4] It was then that he took the pen-name Jasienica (from the name of the place where he had received treatment for his injuries) in order not to endanger his wife, who was still living in Soviet-controlled Vilnius, Lithuania.[6] Soon he became a member of the weekly's staff and then an editor.[3] In 1948 he was arrested by the Polish secret police (Polish: Urząd Bezpieczeństwa) but after several weeks was released after the intervention of Bolesław Piasecki from the PAX Association.[1][3][4][5] In gratitude to Piasecki, he worked with PAX in the future, leaving Tygodnik Powszechny for PAX in 1950.[1][3] From 1950 he was a director of Polish Caritas charity.[3] His essays were published in Dziś i Jutro, Słowo Powszechne, Życie Warszawy, Po Prostu.[3] From at least this period till his death he would live in Warsaw.[2] His wife Władysława died 29 March 1965.[2]

Over time he became increasingly involved in various dissident organizations.[1] In December 1959 he became a vice president of the Union of Polish Writers (Związek Literatów Polskich, ZLP).[1] He also published in the magazine Świat (1951–1969). In 1962 he was the last president of the literary discussion society, Klub Krzywego Koła. In 1966 he was a vice president of the PEN Club.[1] While in the late 1940s and 1950s he focused mostly on journalistic activity, later he turned to writing popular history in book format.[1][3] In the 1960s he wrote his most famous works, historical books about history of Poland - the Kingdom of Poland in the times of the Piast dynasty, the Jagiellonian dynasty, and the era of elected kings (the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth).[1][7] His book on the Jagiellonian Poland was recognized as the best book of the year by the readers.[2]

Jasienica was, however, very outspoken in his criticism of the censorship in the People's Republic of Poland. On 29 February 1968 during a ZLP meeting, Jasienia presented a harsh critique of the government.[2] These acts, and in particular his signing of the dissident Letter of 34 in 1964 against censorship and his involvement in the 1968 protests led to his being labeled a political dissident, for which he suffered government persecution.[1][2][4][5][8] Partly as a response to government's persecution of Jasienica, in 1968 the satirist Janusz Szpotański dedicated one of his anti-government poems, Ballada o Łupaszce (The Ballad of Łupaszko), written while Szpotański was in Mokotów Prison, to the writer.[9] In the aftermath of the 1968 events, Polish communist media, and communist leader, Władysław Gomułka, on 19 March 1968, alleged that in 1948 Jasienica was freed because he collaborated with the communist regime; this allegation caused much controversy and damaged Jasienica's reputation.[2][3][4][5][8] He was subject to much invigilation by the security services.[1] In December 1969, five years after his first wife's death, he became married again. This marriage, after his death, proven to be highly controversial, as his second wife was in fact a secret police informant before the marriage, and continued to write reports about him throughout their marriage.[6][10][11] Since then, till his death, his books were prohibited from being distributed or printed.[1][3][8]

Jasienica died from cancer[8] on 19 August 1970 in Warsaw. Some publicists later speculated to what extent his death was caused by "hounding from the party establishment".[12] He is buried in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery.[2] His funeral was attended by many dissidents and became a political manifestation; Adam Michnik recalls seeing Antoni Słonimski, Stefan Kisielewski, Stanisław Stomma, Jerzy Andrzejewski, Jan Józef Lipski and Władysław Bartoszewski.[8] Bohdan Cywiński read a letter from Antoni Gołubiew.[2][8]

Work

Jasienica book publishing begun with a historical book, Zygmunt August na ziemiach dawnego Wielkiego Księstwa (Sigismund Augustus in the lands of the former Grand Duchy; 1935). He is best known for his highly acclaimed[13] and popular[1] historical books from the 1960s about Piast Poland, Jagiellon Poland and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: Polska Piastów (Piast Poland, 1960), Polska Jagiellonów (Jagiellon Poland, 1963) and the trilogy Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów (The Commonwealth of Both Nations, 1967–1972). This trilogy made him one of the most popular Polish history writers.[1] Throughout his life he avoided writing about modern history, to minimize the influence that the official, communist Marxist historiography would have on his works. This was also one of the reasons for the popularity of his works, which were seen as a rare, legally obtainable alternative to the official version of history.[1][14][15][16] His books, publication of which resumed once again after his death, were labeled as "best-selling", and became the most reprinted postwar history of Poland.[15][16]

His Dwie drogi (Two ways, 1959) about the January Uprising of the 1860s represent the latest historical period he has tackled. His other popular historical books include Trzej kronikarze, (Three chroniclers; 1964), a book about three medieval chroniclers of Polish history (Thietmar of Merseburg, Gallus Anonymus and Wincenty Kadłubek), in which he discusses the Polish society through ages;[17] and Ostatnia z rodu (Last of the Family; 1965) about the last queen of the Jagiellon dynasty, Anna Jagiellonka. His Rozważania o wojnie domowej (1978; Thoughts on Civil War) were the last book he has finished; unlike majority of his other works, this book is ostensibly about the civil war (Chouannerie) in Brittany, France. This work does however contains numerous arguments applicable to more modern Polish history; arguments that Jasienica thought would not be allowed by the censors if the book discussed Polish history.[8]

In addition to historical books, Jasienica, wrote a series of essays about archeology - Słowiański rodowód (Slavic genealogy; 1961) and Archeologia na wyrywki. Reportaże (Archeological excerpts: reports; 1956), journalistic travel reports (Wisła pożegna zaścianek, Kraj Nad Jangtse) and science and technology (Opowieści o żywej materii, Zakotwiczeni). Those works were mostly created around the 1950s and 1960s.

His Pamiętnik (Diary) was the work that he begun shortly before his death, and that was never finished.

In 2006, Polish journalist and former dissident Adam Michnik said that:

I belong to the generation '68, a generation that has special debt to Paweł Jasienica - in fact he paid with his life for daring to defend us, the youth. I want for somebody to be able to write, at some point, that in my generation there were people who stayed true to his message. Those who never forgot about his beautiful life, his wise and brave books, his terrible tragedy.[8]

Polish historian Henryk Samsonowicz echoes Michnik's essay in his introduction to a recent (2008) edition of Trzej kronikarze, describing Jasienica as a person who did much to popularize Polish history.[17] Hungarian historian Balázs Trencsényi notes that "Jasienica's impact of the formation of the popular interpretation of Polish history is hard to overestimate".[14] British historian Norman Davies, himself an author of a popular account of Polish history (God's Playground), notes that Jasienica, while more of "a historical writer than an academic historian", had "formidable talents", gained "much popularity" and that his works would find no equals in the time of communist Poland.[16] Samsonowicz notes that Jasienica "was a brave writer", going against prevailing system, and willing to propose new hypotheses and reinterpret history in innovative ways.[17] Michnik notes how Jasienica was willing to write about Polish mistakes, for example in the treatment of Cossacks.[8] Ukrainian historian Stephen Velychenko also positively commented on Jasienica's extensive coverage of the Polish-Ukrainian history.[15] Both Michnik and Samsonowicz note how Jasienica's works contain hidden messages in which Jasienica discusses more contemporary history, such as in his Rozważania....[8][17][18]

Bibliography

Several of Jasienica's books have been translated into English by Alexander Jordan and published by the American Institute of Polish Culture, based in Miami, Florida.

- Zygmunt August na ziemiach dawnego Wielkiego Księstwa (Sigismund Augustus on the lands of the former Grand Duchy; 1935)

- Ziemie północno-wschodnie Rzeczypospolitej za Sasów (North-eastern lands of the Commonwealth during the Sas dynasty; 1939)

- Wisła pożegna zaścianek (Vistula will say farewell to gentry's province; 1951)

- Świt słowiańskiego jutra (Dawn of the Slavic tomorrow; 1952)

- Biały front (White front, 1953)

- Opowieści o żywej materii (Tales of living matter; 1954)

- Zakotwiczeni (Moored; 1955)

- Chodzi o Polskę (It's about Poland; 1956)

- Archeologia na wyrywki. Reportaże (Archeological excerpts: reports; 1956; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-085-5)

- Ślady potyczek (Traces of battles; 1957; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-196-8)

- Kraj Nad Jangtse (Country at Yangtze; 1957; latest Polish edition from 2008 uses the Kraj na Jangcy title; ISBN 978-83-7469-798-9)

- Dwie drogi (Two ways; 1959; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-89325-28-0)

- Myśli o dawnej Polsce (Thoughts about Old Poland; 1960; latest Polish edition 1990; ISBN 83-07-01957-5)

- Polska Piastów (1960; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-479-7), translated as Piast Poland (1985; ISBN 0-87052-134-9)

- Słowiański rodowód (Slavic genealogy; 1961, latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-705-7)

- Tylko o historii (Only about History; 1962, latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-267-5)

- Polska Jagiellonów (1963; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-522-0), translated as Jagiellonian Poland (1978; ISBN 978-1-881284-01-7)

- Trzej kronikarze (Three chroniclers; 1964; latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-750-7)

- Ostatnia z rodu (Last of the Family; 1965; latest Polish edition 2009; ISBN 978-83-7648-135-7)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów (1967–1972), translated as The Commonwealth of Both Nations; 1987, ISBN 0-87052-394-5), often published in three separate volumes:

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.1: Srebrny wiek (1967; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-580-0), translated as 'The Commonwealth of Both Nations I: The Silver Age (1992; ISBN 0-87052-394-5)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.2: Calamitatis Regnum (1967; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-582-4)), translated as 'The Commonwealth of Both Nations II: Calamity of the Realm (1992; ISBN 1-881284-03-4)

- Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów t.3: Dzieje agoni (1972; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-583-1), translated as 'The Commonwealth of Both Nations III: A Tale of Agony (1992; ISBN 1-881284-04-2)

- Rozważania o wojnie domowej (Thoughts on Civil War; 1978; latest Polish edition 2008)

- Pamiętnik (Diary; 1985; latest Polish edition 2007; ISBN 978-83-7469-612-8)

- Polska anarchia (Polish Anarchy; 1988; latest Polish edition 2008; ISBN 978-83-7469-880-1)

Awards

- Medals:

- Order of Polonia Restituta, Grand Cross, awarded on 3 May 2007 (posthumously)[17]

- Order of Polonia Restituta, Knight's Cross, awarded on 22 July 1956

- Cross of Valour, awarded by the Wilno Region Headquarters of Armia Krajowa in 1944, confirmed by Polish Ministry of Defense in 1967

- Armia Krajowa Cross, awarded in 1967 in London

- Awards:

- 2007 laureate of Poland's "Custodian of National Memory" Prize.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 (Polish) Paweł Jasienica (1909–1970), Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 (Polish) Aleksandra Gromek Gadkowska, PAWEŁ JASIENICA, 2 March 2011. Retrieved on 23 April 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 (Polish) Zbigniew Żbikowski, Paweł Jasienica: Kapitan martwej armii, Życie, 14 April 2001. Retrieved 18 April 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tadeusz Borowski; Tadeusz Drewnowski; Alicia Nitecki (2007). Postal indiscretions: the correspondence of Tadeusz Borowski. Northwestern University Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-8101-2203-1. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (Polish) Prawa autorskie po Jasienicy tylko dla jego córki, gazeta.pl, 28 December 2006. Retrieved 18 April 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Polish) Helena Kowalik, Ubeckie donosy z sypialni', trop-reportera.pl. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Stanley S. Sokol; Sharon F. Mrotek Kissane; Alfred L. Abramowicz (1992). The Polish biographical dictionary: profiles of nearly 900 Poles who have made lasting contributions to world civilization. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-86516-245-7. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (Polish) Michnik o Jasienicy: pisarz w obcęgach, Gazeta Wyborcza, 28 September 2006

- ↑ (Polish) Janusz Szpotański, Ballada o Łupaszce, last accessed 4/19/2011

- ↑ (Polish) Piotr Jezierski, Uwieść Jasienicę, Historia, Polskie Radio. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ (Polish) Cezary Łazarewicz,Nesia wszystko doniesie Polityka, 12 March 2010 r. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Adam Michnik (2 May 2011). In Search of Lost Meaning: The New Eastern Europe. University of California Press. p. 214–. ISBN 978-0-520-26923-1. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- ↑ Antony Polonsky; Joanna B. Michlic (2004). The neighbors respond: the controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland. Princeton University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-691-11306-7. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 Balázs Trencsényi (2007). Narratives unbound: historical studies in post-communist Eastern Europe. Central European University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-963-7326-85-1. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Stephen Velychenko (1993). Shaping identity in Eastern Europe and Russia: Soviet-Russian and Polish accounts of Ukrainian history, 1914-1991. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-312-08552-0. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 Norman Davies (30 March 2005). God's Playground: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Polish) Henryk Samsonowicz, Wstęp, in Paweł Jasienica, Trzej kronikarze, 2008 edition

- ↑ Marcin Kula (2004). Krótki raport o użytkowaniu historii. Wydawn. Naukowe PWN. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-83-01-14227-8. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- ↑ (Polish) Rok 2007 - Uroczystość wręczenia Nagrody Kustosz Pamięci Narodowej, ipn.gov.pl, Retrieved 18 April 2011.

Further reading

- Marian Brandys, Jasienica i inni (Jasienica and Others), Warsaw, Iskry, 1995, ISBN 83-207-1492-3

- Bernard Wiaderny, Paweł Jasienica: Fragment biografii, wrzesien 1939 – brygada Łupaszki, 1945 (Paweł Jasienica: Fragment of a Biography, September 1939 – Łupaszko's Brigade, 1945); Warsaw, Antyk

- Ewa Beynar-Czeczott, Mój ojciec Paweł Jasienica (My father Paweł Jasienica); Prószyński i S-ka 2006, ISBN 83-7469-437-8)

![]() Polish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paweł Jasienica

Polish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paweł Jasienica

|