Pauli equation

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli equation or Schrödinger–Pauli equation is the formulation of the Schrödinger equation for spin-½ particles, which takes into account the interaction of the particle's spin with an external electromagnetic field. It is the non-relativistic limit of the Dirac equation and can be used where particles are moving at speeds much less than the speed of light, so that relativistic effects can be neglected. It was formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1927.[1]

Equation

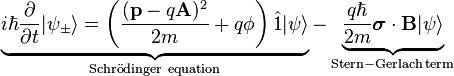

For a particle of mass m and charge q, in an electromagnetic field described by the vector potential A = (Ax, Ay, Az) and scalar electric potential ϕ, the Pauli equation reads:

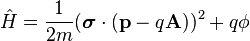

Pauli equation (general) ![\left[ \frac{1}{2m}(\boldsymbol{\sigma}\cdot(\mathbf{p} - q \mathbf{A}))^2 + q \phi \right] |\psi\rangle = i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} |\psi\rangle](../I/m/4edf587d205900f46fdb16df27d2b4a1.png)

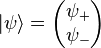

where σ = (σx, σy, σz) are the Pauli matrices collected into a vector for convenience, p = −iħ∇ is the momentum operator wherein ∇ denotes the gradient operator, and

is the two-component spinor wavefunction, a column vector written in Dirac notation.

is a 2 × 2 matrix operator, because of the Pauli matrices. Substitution into the Schrödinger equation gives the Pauli equation. This Hamiltonian is similar to the classical Hamiltonian for a charged particle interacting with an electromagnetic field, see Lorentz force for details of this classical case. The kinetic energy term for a free particle in the absence of an electromagnetic field is just p2/2m where p is the kinetic momentum, while in the presence of an EM field we have the minimal coupling p = P − qA, where P is the canonical momentum.

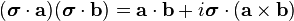

The Pauli matrices can be removed from the kinetic energy term, using the Pauli vector identity:

to obtain[2]

Pauli equation (standard form) ![\hat{H} |\psi\rangle = \left[\frac{1}{2m}\left[\left(\mathbf{p} - q \mathbf{A}\right)^2 - q \hbar \boldsymbol{\sigma}\cdot \mathbf{B}\right] + q \phi\right]|\psi\rangle = i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} |\psi\rangle](../I/m/4e5c00f7f1870e55343f3a881cc36c17.png)

where B = ∇ × A is the magnetic field.

Relationship with the Schrödinger equation and the Dirac equation

The Pauli equation is non-relativistic, but it does predict spin. As such, it can be thought of as occupying the middle ground between:

- The familiar Schrödinger equation (on a complex scalar wavefunction), which is non-relativistic and does not predict spin.

- The Dirac equation (on a complex four-component spinor), which is fully relativistic (with respect to special relativity) and predicts spin.

Note that because of the properties of the Pauli matrices, if the magnetic vector potential A is equal to zero, then the equation reduces to the familiar Schrödinger equation for a particle in a purely electric potential ϕ, except that it operates on a two-component spinor:

Therefore, we can see that the spin of the particle only affects its motion in the presence of a magnetic field.

Relationship with Stern–Gerlach experiment

Both spinor components satisfy the Schrödinger equation. For a particle in an externally applied B field, the Pauli equation reads:

Pauli equation (B-field)

where

is the 2 × 2 identity matrix, which acts as an identity operator.

The Stern–Gerlach term can obtain the spin orientation of atoms with one valence electron, e.g. silver atoms which flow through an inhomogeneous magnetic field.

Analogously, the term is responsible for the splitting of spectral lines (corresponding to energy levels) in a magnetic field as can be viewed in the anomalous Zeeman effect.

See also

References

- Schwabl, Franz (2004). Quantenmechanik I. Springer. ISBN 978-3540431060.

- Schwabl, Franz (2005). Quantenmechanik für Fortgeschrittene. Springer. ISBN 978-3540259046.

- Claude Cohen-Tannoudji, Bernard Diu, Frank Laloe (2006). Quantum Mechanics 2. Wiley, J. ISBN 978-0471569527.

![\left[ \frac{\mathbf{p}^2}{2m} + q \phi \right] \begin{pmatrix}

\psi_+ \\

\psi_-

\end{pmatrix} = i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \begin{pmatrix}

\psi_+ \\

\psi_-

\end{pmatrix}.](../I/m/1fedf162fef34df307e34ed97084aeb5.png)