Partial fractions in complex analysis

In complex analysis, a partial fraction expansion is a way of writing a meromorphic function f(z) as an infinite sum of rational functions and polynomials. When f(z) is a rational function, this reduces to the usual method of partial fractions.

Motivation

By using polynomial long division and the partial fraction technique from algebra, any rational function can be written as a sum of terms of the form 1 / (az + b)k + p(z), where a and b are complex, k is an integer, and p(z) is a polynomial . Just as polynomial factorization can be generalized to the Weierstrass factorization theorem, there is an analogy to partial fraction expansions for certain meromorphic functions.

A proper rational function, i.e. one for which the degree of the denominator is greater than the degree of the numerator, has a partial fraction expansion with no polynomial terms. Similarly, a meromorphic function f(z) for which |f(z)| goes to 0 as z goes to infinity at least as quickly as |1/z|, has an expansion with no polynomial terms.

Calculation

Let f(z) be a function meromorphic in the finite complex plane with poles at λ1, λ2, ..., and let (Γ1, Γ2, ...) be a sequence of simple closed curves such that:

- The origin lies inside each curve Γk

- No curve passes through a pole of f

- Γk lies inside Γk+1 for all k

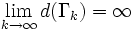

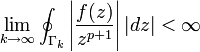

-

, where d(Γk) gives the distance from the curve to the origin

, where d(Γk) gives the distance from the curve to the origin

Suppose also that there exists an integer p such that

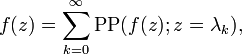

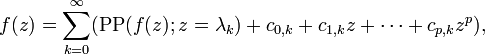

Writing PP(f(z); z = λk) for the principal part of the Laurent expansion of f about the point λk, we have

if p = -1, and if p > -1,

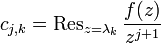

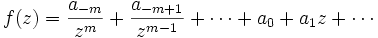

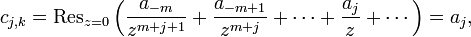

where the coefficients cj,k are given by

λ0 should be set to 0, because even if f(z) itself does not have a pole at 0, the residues of f(z)/zj+1 at z = 0 must still be included in the sum.

Note that in the case of λ0 = 0, we can use the Laurent expansion of f(z) about the origin to get

so that the polynomial terms contributed are exactly the regular part of the Laurent series up to zp.

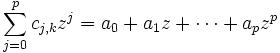

For the other poles λk where k ≥ 1, 1/zj+1 can be pulled out of the residue calculations:

To avoid issues with convergence, the poles should be ordered so that if λk is inside Γn, then λj is also inside Γn for all j < k.

Example

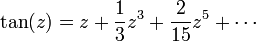

The simplest examples of meromorphic functions with an infinite number of poles are the non-entire trigonometric functions, so take the function tan(z). tan(z) is meromorphic with poles at (n + 1/2)π, n = 0, ±1, ±2, ... The contours Γk will be squares with vertices at ±πk ± πki traversed counterclockwise, k > 1, which are easily seen to satisfy the necessary conditions.

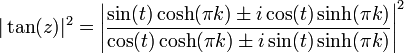

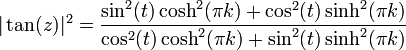

On the horizontal sides of Γk,

so

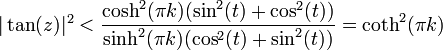

sinh(x) < cosh(x) for all real x, which yields

For x > 0, coth(x) is continuous, decreasing, and bounded below by 1, so it follows that on the horizontal sides of Γk, |tan(z)| < coth(π). Similarly, it can be shown that |tan(z)| < 1 on the vertical sides of Γk.

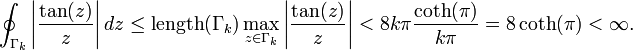

With this bound on |tan(z)| we can see that

(The maximum of |1/z| on Γk occurs at the minimum of |z|, which is kπ).

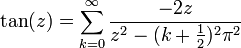

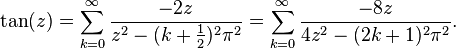

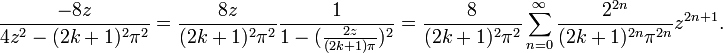

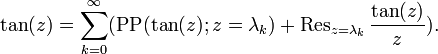

Therefore p = 0, and the partial fraction expansion of tan(z) looks like

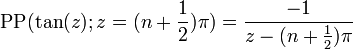

The principal parts and residues are easy enough to calculate, as all the poles of tan(z) are simple and have residue -1:

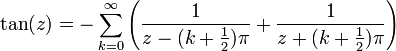

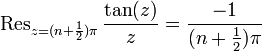

We can ignore λ0 = 0, since both tan(z) and tan(z)/z are analytic at 0, so there is no contribution to the sum, and ordering the poles λk so that λ1 = π/2, λ2 = -π/2, λ3 = 3π/2, etc., gives

Applications

Infinite products

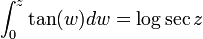

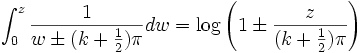

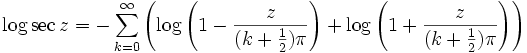

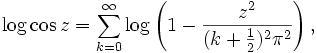

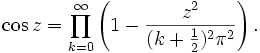

Because the partial fraction expansion often yields sums of 1/(a+bz), it can be useful in finding a way to write a function as an infinite product; integrating both sides gives a sum of logarithms, and exponentiating gives the desired product:

Applying some logarithm rules,

which finally gives

Laurent series

The partial fraction expansion for a function can also be used to find a Laurent series for it by simply replacing the rational functions in the sum with their Laurent series, which are often not difficult to write in closed form. This can also lead to interesting identities if a Laurent series is already known.

Recall that

We can expand the summand using a geometric series:

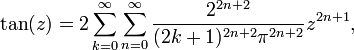

Substituting back,

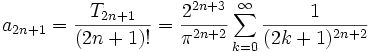

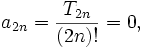

which shows that the coefficients an in the Laurent (Taylor) series of tan(z) about z = 0 are

where Tn are the tangent numbers.

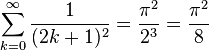

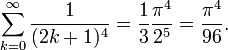

Conversely, we can compare this formula to the Taylor expansion for tan(z) about z = 0 to calculate the infinite sums:

See also

References

- Markushevich, A.I. Theory of functions of a complex variable. Trans. Richard A. Silverman. Vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1965.

![\sum_{j=0}^p c_{j,k}z^j = [\operatorname{Res}_{z=\lambda_k} f(z)] \sum_{j=0}^p \frac{1}{\lambda_k^{j+1}} z^j](../I/m/9e2ce47b9447753f111d5e177a902af0.png)

![z = t \pm \pi k i,\ \ t \in [-\pi k, \pi k],](../I/m/64dbae5a41e0ea4eadc30ea8f363bddd.png)

![\tan(z) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \left[\left(\frac{-1}{z - (k + \frac{1}{2})\pi} - \frac{1}{(k + \frac{1}{2})\pi}\right) + \left(\frac{-1}{z + (k + \frac{1}{2})\pi} + \frac{1}{(k + \frac{1}{2})\pi}\right)\right]](../I/m/0411d1af8334a546c2fe1f529ee1fce1.png)