Parnassus plays

The Parnassus plays are three satiric comedies that were performed as part of the Christmas festivities by students of St John's College at Cambridge University in London. It is not known who wrote them, but they date from between 1598 and 1602.[1] For the most part, the three plays follow the experiences of two students, Philomusus and Studioso. The first play, The Pilgrimage to Parnassus, tells the story of two pilgrims on a journey to Parnassus. The plot is an allegory understood to represent the story of two students progressing through the traditional medieval course of education known as the Trivium. The accomplishment of their education is represented by Mount Parnassus. The second play, The Return from Parnassus, drops the allegory and describes the two graduates' unsuccessful attempts to make a living. As does the third play, The Return from Parnassus: Or the Scourge of Simony, which is the only one that was contemporaneously published.[2]

It has been said that this trilogy of plays “in originality and breadth of execution, and in complex relationship to the academic, literary, theatrical and social life of the period, ranks supreme among the extant memorials of the university stage.”[3]And that they are “among the most inexplicably neglected key documents of Shakespeare’s age.”[4]

The plays

The first part, The Pilgrimage to Parnassus, describes allegorically the progress of the two students through the university courses of logic, rhetoric, and grammar, and the temptations that are set before them by their meeting with Madido, a drunkard, Stupido, a puritan who hates learning, Amoretto, a lover, and Ingenioso, a disappointed student.

The first play was doubtlessly intended to stand alone, but the favour with which it was received led to the writing of a sequel, The Return from Parnassus, which deals with the struggles of the two students after the completion of their studies at the university, and shows them discovering by bitter experience of how little pecuniary value their learning is.

A further sequel, The Return from Parnassus, Or the Scourge of Simony, is a more ambitious, and from every point of view more interesting than the two earlier plays. A knowledge of what occurs in the first two plays is helpful, in order to understand some of the allusions made by Ingenioso, Studioso and Philomusus in the third play, The Return from Parnassus: Or the Scourge of Simony, but it’s not required.

Synopsis of The Pilgrimage to Parnassus

|

|

An old farmer, Consiliodorus, gives advice to his son, Philomusus, and his nephew, Studioso, as the two young men are about to begin their journey to Parnassus. The two young men say goodbye to Consiliodorus. The first place they travel through is the land of Logique, where they encounter Madido, who urges them not to bother with their journey, but to stay and drink with him. They decline and continue on.

Next, in the land of Rhetorique, Philomusus and Studioso overtake a character named Stupido, a fellow pilgrim, who has so far been traveling for ten years. Stupido’s uncle, in a letter, has advised him to give up the journey and to recognize that there is no value in studies.

Philomusus and Studioso then encounter, Amaretto, who sees himself as a great lover. Amaretto encourages them to leave their pilgrimage, and instead linger in the land of Poetry and dally with wenches. This time Philomusus and Studioso are persuaded and abandon, at least for a while, the path to Parnassus.

Before it’s too late, Philomusus and Studioso have come to their senses, have decided to leave the amorous land of poetry. They continue on, and meet a character who is former student, Ingenioso. He tries to discourage Philomusus and Studioso from their pilgrimage by telling them that there is nothing but poverty on Mount Parnassus. Dromo enters drawing on a clown by a rope, because he feels that every play needs a clown. They finally arrive at the foothills of Mount Parnassus, and take a moment to gaze up at it in a spirit of celebration. Studioso invites the audience to applaud.

Synopsis of The Return from Parnassus

|

|

Consiliodorus, father to Philomusus and uncle to Studioso is meeting with a messenger, Leonarde, who will deliver a letter to Philomusus and Studioso. He sent those two young men to on a journey seven years ago, and now expects results. Consiliodorus exits as Philomusus and Studioso enter, both bemoaning that since leaving Parnassus fate hasn’t been kind and the world is not a fruitful place for scholars. They meet a former student, Ingenioso, who tells them he has been living by the printing house and selling pamphlets. Now he is pursuing the support of a patron. The patron appears, and Ingenioso offers him immortality through his verse. Ingenioso then offers the patron a pamphlet that is dedicated to him. The patron glances at it, gives Ingenioso two small coins, and exits. Ingenioso, alone, is furious with the patron’s miserliness. Philomusus and Studioso reenter to hear how it went. Ingenioso now plans to go to London and live by the printers trade. Philomusus and Studioso decide to go along, and include Luxuioso, who has also left Parnassus to go to London. The four, now former students, take a moment to bid farewell to Parnassus.

The Draper and the Tayler, local businessmen both both complain that they trusted Philomusus and Studioso, did some draping and tailoring, and Philomusus and Studioso ran away owing them money. The tapsters has a similar problem with another former student, Luxuioso. Philomusus and Studioso meet up, both complain of the lowly jobs they have taken, Philomusus is a sexton/gravedigger, and Studioso is a household servant, farmhand, waiter and tutor. Percevall enters with a grave-digging job for Philomusus. Percevall wants Philomusus to quickly dig a grave for his father, who may not be dead yet, but will be very soon. He also wants Philomusus to write out the soon-to-be-dead father’s will so that Percevall will inherit his fortune. Next Studioso enters with the boy he is tutoring, and attempts to give a lesson in Latin grammar. Then Luxurio and a boy enter, on the way to a fair. Luxurio has written some poems and plans to sell them at the fair by having the boy recite them. They give a demonstration.

Ingenioso has found a kind of patron in Gullio, a character that is partly based on Thomas Nashe’s portrait of “an upstart” in his pamphlet Pierce Penniless. Gullio “maintains” Ingenioso very neglectfully. Foppishly dressed Gullio falsely boasts of being a valiant, noble and romantic character. Ingenioso offers himself as a poet to memorialize Gullio in sonnets. Gullio then persuades Ingenioso to impersonate his mistress, Lesbia, while Gullio rehearses love poetry that Gullio himself has written and derived from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Venus and Adonis. Gullio plans to eventually recite these verses as part of his wooing of Lesbia. In the next scene, Consiliodorus, father to Philomusus, uncle to Studioso, who funded their journey to Parnassus meets with the carrier and horse-back messenger Leonarde. Leonarde reports that he scolded Philomusus and Studioso and reminded them that their nurturing was costly. Leonarde thinks they may have found jobs as clerks. Consiliodorus is disappointed they are not doing as well as they should be doing.

Ingenioso composes amorous verses in the styles of Chaucer, Spenser, and William Shakespeare, the last alone being to the patron's satisfaction. Gullio, a great admirer of "sweet Mr. Shakespeare", says he will obtain a picture of him for his study and will "worship sweet Mr Shakespeare and to honour him will lay his Venus and Adonis under my pillow, as we read of one – I do not well remember his name, but I'm sure he was a king – slept with Homer under his bed's head". Percevall enters. He has a new position as the church warden and is now referred to as Mr. Warden. He’s looking for the Sexton, who is Philomusus. Philomusus hasn’t been doing a good job as Sexton, and Perceval informs him he is no longer the Sexton. Studioso then enters, he has also lost his position, which was to be tutor to a young boy and perform other household tasks. These two protagonists have reached a depth of hopeless misery ill-equipped for a world that does not appreciate scholars. At least they have each other, as they dejectedly agree to go wandering off in poverty together.

Ingenioso’s foolosh patron, Gullio, had asked Ingenioso to write and deliver poetic messages to a young woman. This goes badly, Gullio blames Ingenioso, and yet another former scholar, Ingenioso, loses his position. Rather than go wandering off like Studioso and Philomusus, he plans to somehow compose and publish satires.

Luxurio appears along with the boy. Luxurio’s attempt to sell his poems has not been fruitful, and he is now broke. He bids farewell to poetry. He intends to go away, drink the world dry, as he accepts his status as a beggar.

Synopsis of The Return from Parnassus; Or the Scourge of Simony

|

|

Before the play begins, Studioso and Philomusus travelled to Rome with the expectation of becoming rich, but they discovered that expatriate Englishmen don’t live as well as they had hoped. They then travelled around, and tried various honest jobs, but now they have run out of such opportunities, and must therefore turn to dishonest work. They establish a medical practice in London, with Philomusus masquerading as a fashionable French doctor, but they end that charade in time to avoid arrest.

Ingenioso has now become a satirist. On the excuse of discussing a recently published collection of extracts from contemporary poetry, John Bodenham's Belvedere, he briefly criticises a number of writers of the day, including Edmund Spenser, Henry Constable, Michael Drayton, John Davies, John Marston, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, Shakespeare, and Thomas Nashe; the last of whom is referred to as dead. Ingenioso attempts to sell a book to Danter, who is a printer. (He is based on an actual person, John Danter.) Ingenioso's last book lost money, but his new one is more promising, it’s about cuckolds in Cambridge.

Needing employment, Academico finds his old friend from college, Amaretto, whose father, Sir Raderick, has a position as a parson to offer. But Amoretto has just accepted a bribe to give it to Immerito. Amoretto pretends not to recognize Academico, and gets rid of him by an off-putting and lengthy discourse regarding technicalities of hunting. Immerito is examined by Sir Radeerick and the Recorder, who find him educated and pliable enough for the job. This practice of selling church positions is “simony”, which is referred to in the subtitle of this play.

Sir Raderick is worried about certain libels written about his family, which are going around in London. They are being written in verse by Furor Poeticus at the encouragement of Ingenioso. A confrontation occurs between the poets and sir Raderick, after he has taken possession of Prodigo’s forfeited land.

Studioso and Philomusus attempt other jobs. They apply to Richard Burbage's theatre hoping to becoming actors, but they realize that actors don’t get paid enough. They are engaged by a company of fiddlers, but their first performance is at the front door of Sir Raderick’s house. The pages of Sir Raderick and Amoretto pretend to be their masters, and dismiss the fiddlers with out payment. At last, Studioso and Philomusus decide to work as shepherds in Kent, while Ingenioso and Furor have to escape to the Isle of Dogs. Academico goes back to Cambridge.

Authorship, dating and meaning

It is not known if they were all the work of one person. John Weever, the satirist Joseph Hall and the dramatist John Day have been proposed as possible authors. The three pieces were evidently performed at Christmas of different years, the last being not later than Christmas 1602, as is shown by the references to Queen Elizabeth I, while the Pilgrimage mentions books not printed until 1598, and hence can hardly have been earlier than that year. The prologue of The Return from Parnassus: Or the Scourge of Simony states that that play had been written for the preceding year, and also, in a passage of which the reading is somewhat doubtful, implies that the whole series had extended over four years. Thus we arrive at either 1599, 1600 and 1602, or 1598, 1599 and 1601, as, on the whole, the most likely dates of performance. Frederick Gard Fleay, on grounds which do not seem conclusive, dates them 1598, 1601 and 1602.

The question of how far the characters are meant to represent actual persons has been much discussed. Fleay maintains that the whole is a personal satire, his identifications of the chief characters in The Return from Parnassus: Or the Scourge of Simony being (1) Ingenioso, Thomas Nashe, (2) Furor Poeticus, J. Marston, (3) Phantasma, Sir John Davies, (4) Philomusus, T. Lodge, (5) Studioso, Drayton. Israel Gollancz identifies Judicio with Henry Chettle (Proc. of Brit. Acad., 1903–1904, p. 202). Dr. Ward, while rejecting Fleays identifications as a whole, considers that by the time the final part was written the author may have more or less identified Ingenioso with Nashe, though the character was not originally conceived with this intention. This is of course possible, and the fact that Ingenioso himself speaks in praise of Nashe, who is regarded as dead, is not an insuperable objection. We must not, however, overlook the fact that the author was evidently very familiar with Nashe's works, and that all three parts, not only in the speeches of Ingenioso, but throughout, are full of reminiscences of his writings.

More recent authors consider the character of "Studioso" being used to satirize Shakespeare.[5][6]

The college recorder, Francis Brackyn was an actual person, who is harshly satirized in The Return from Parnassus: Or the Scourge of Simony as the character “Recorder”. Brackyn would be ridiculed yet again as the title character in another university play, Ignoramus.[7]

Printing history

The only part of the trilogy which was in print at an early date was The Return from Parnassus, or the Scourge of Simony (1606), two editions bearing the same date. This has been several times reprinted, including the edition of Professor Arber in the English Scholars' Library (1879). Manuscript copies of all three plays were found in the manuscript collection of Thomas Hearne preserved in the Bodleian Library by the Rev. Rev. William Macray, which he printed in 1868. (The text of The Return from Parnassus, or the Scourge of Simony was based on one of the editions of 1606, collated with the manuscript.) A recent edition (as of 1911) in modern spelling by Mr O. Smeaton in the Temple Dramatists is of little value. All questions connected with the play have been elaborately discussed by Dr. W. Lühr in a dissertation entitled Die drei cambridger Spiele vom Parnass (Kiel, 1900). See also, Dr. Ward's English Dramatic Literature, ii. 633–642; F. G. Fleay's Biog. Chron. of the Eng. Drama, ii. 347–355.

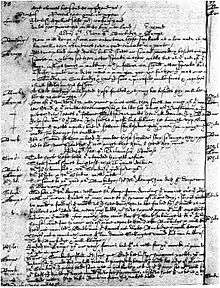

The two earlier plays were not known until Rev. Macray discovered them in the Hearne manuscript collection. The manuscript for The Return from Parnassus, or the Scourge of Simony (which titles the play The Progresse to Parnassus) is housed in the Folger Shakespeare Library. The most recent edition of the plays appeared in 1949, edited by the Oxford scholar J. B. Leishman.

A book-length treatment of the Parnassus plays is Paula Glatzer's The Complaint of the Poet: The Parnassus Plays published in 1977. [8]

A reading

A rehearsed reading of the Return from Parnassus, or The Scourge of Simony was performed 6 December 2009 as part of Shakespeare's Globe Theatre's Read Not Dead series. The cast included David Oakes as Ingenioso.

References

- ↑ Muir, Andrew. Shakespeare in Cambridge. Amberley Publishing Limited, 2015. ISBN 9781445641140

- ↑ Reyburn, Marjorie. New Facts and Theories about the Parnassus Plays. PMLA. Vol. 74, No. 4 (Sep., 1959). pp. 325-335. Modern Language Association.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes (1907–21). Volume VI. The Drama to 1642, Part Two. XII. University Plays. § 16. The Parnassus Trilogy.

- ↑ Sams, Eric. The Real Shakespeare; Retrieving the Early Years, 1564 —1594. Yale University Press. 1995 page 86.

- ↑ Ackroyd, Peter. Shakespeare the Biography. Chatto & Windus, 2005, pg 77

- ↑ Sams, Eric. '’The Real Shakespeare; Retrieving the Early Years, 1564–1594’’. Yale University Press 1995, pg 37

- ↑ Marlow, Christopher. Performing Masculinity in English University Drama, 1598-1636. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. (2013) ISBN 9781472405166

- ↑ Glatzer, Paula. The Complaint of the Poet: The Parnassus Plays: a Critical Study of the Trilogy Performed at St. John's College, Cambridge, 1598/99-1601/02, Authors Anonymous. The Edwin Mellen Press (1977) ISBN 978-0779938070

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ronald Brunlees McKerrow (1911). "Parnassus Plays". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ronald Brunlees McKerrow (1911). "Parnassus Plays". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Digital reproduction of the handwritten manuscript of The Return from Parnassus, or the Scourge of Simony [erroneously titled Progress to Parnassus] in the Folger Shakespeare Library Digital Image Collection