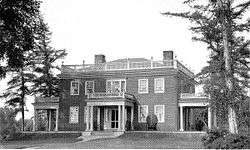

Parker House (Blue Hill, Maine)

|

Parker House | |

| |

|

Photograph c. 1900 | |

| |

| Location | 185 South St., Blue Hill, Maine |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 44°23′49″N 68°35′19″W / 44.39694°N 68.58861°WCoordinates: 44°23′49″N 68°35′19″W / 44.39694°N 68.58861°W |

| Area | 5.8 acres (2.3 ha) |

| Built | 1816 |

| Architect | Clough, George A. |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP Reference # | 04001047[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 22, 2004 |

Parker House is an historic house at 185 South Street in Blue Hill, Maine. Built c. 1816 and substantially updated in the Colonial Revival style in 1900 to a design by George Albert Clough, the house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004 for its architectural significance.

Description and history

Parker House is believed to have been constructed for Robert Parker and his wife Ruth, a daughter of Blue Hill founder Joseph Wood, in 1816 (or possibly in 1812), on an upland portion of the Parker family land grants of which Parker Point[2] was also part. After passing to other owners including Frederick Fisher, grandson of Blue Hill's first settled minister Jonathan Fisher, the house was remodeled in 1900 by George A. Clough for Mrs. Frederick Augustus Merrill, a resident of Boston descended from Ruth Parker's sister, Edith Wood Hinckley, the first child of early settlers to be born in Blue Hill.[3]

Parker House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places both for the quality of its original features and for changes made by Clough in the Colonial Revival spirit. The house contains much original woodwork including several fine fireplaces; Clough's contributions included Tuscan-columned porches and the addition of a (now removed) wrap-around veranda and balustrades on the roofs. Prior to designation the present owner altered the interior using a device Clough's more famous contemporary John Calvin Stevens had employed when remodeling the Federal Elias Thomas House in Portland, Maine, combining two downstairs rooms and marking the transition with a screen of columns and pilasters.[4]

The classical mode of the Colonial Revival was considered an advancement in taste over the earlier, more rustic Shingle Style, but at this period - especially after 1893, the year of the Columbian Exposition - the style began to have associations with retrograde social politics, specifically nativism.[5] Under pressure from below by the growing political influence of recent immigrants and from above by the social dominance of Gilded Age nouveaux riches, old families around the dawn of the 20th century tended to insist somewhat on their gentility, and often chose to imbue a sense of family history into the design and decoration of their houses.

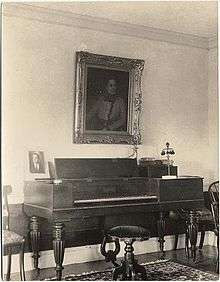

The Merrills were no exception. They filled Parker House with oil portraits by family friend J. Harvey Young, (the one of Mrs. Merrill's mother Mary Peters Hinckley Ober painted posthumously), and with antiques with family provenance, a few wrested from local cousins, creating for themselves a kind of ersatz ancestral home. (It seems clear this had long been their intention: their daughters Edith and Ruth, born in the 1880s, shared the names of two of Joseph Wood's.[6]). Among such acquisitions was a table which came up from Beverly with Joseph Wood, later given to the Blue Hill Historical Society by Mrs. Merrill's granddaughter, Betty Darling Bates.[7] (It can be seen at Holt House, the Society's headquarters,[8] built by Stephen Holt and his wife Edith, youngest of the Parker daughters).[9] There was also the inevitable spinning wheel, a Peters family heirloom, still in the house but now banished upstairs.

This sense of created history extended to legends concerning the house's construction, traditionally assumed to be complete before 1813. (This would have had to be the case for the tale of Joseph Wood dying in the house to be true). The story of workmen on the roof hearing the guns at Castine signaling the commencement of the War of 1812, dropping everything in their haste to join the fight then returning to pick up rusty tools where they'd fallen is surely apocryphal, being just the sort of tale conjured up at the time to romanticize the patriotic spirit of early Americans.

Yet with Civil War era anti-draft riots and lynchings of free blacks by protestors vivid in the memory of many living in 1900, being less remote in time than the Vietnam War and Watergate are to us, such stories may have had particular meaning to New Englanders[10] steeped in the traditions of Abolitionism and military service: Mrs. Merrill's elder brother had fought under Grant[11] and she was proud to be descended from Nehemiah Hinckley, Edith Wood's husband, a Blue Hill soldier who walked home from West Point after the Revolution.

As remodeled, Parker House was emphatically a summer home - Clough's French windows were not designed to keep out winter chills - but was also conceived as a place in the country. Inspired by the House and Garden Movement,[12] in the fashion of the day Mrs. Merrill kept a Jersey cow and laying hens, unthinkable on Parker Point where the family had previously summered. She also cultivated gladiolus in her garden, entering them at the annual Blue Hill Fair,[13] and, in the spirit of agricultural improvement then abroad in the land, engaged Frederick Vernon Coville, the developer of the modern Highbush Blueberry, to plant a number of his early cultivars on the property. (His services did not come cheap. According to her granddaughter's recollections, Mrs. Merrill would sometimes say to guests to whom she served any, "Did you enjoy the berries? They cost me a nickel apiece.") Fashionable too were her artistic pursuits. The house contains two oil still-lives and a set of hand-painted Limoges china as well as examples of her needlepoint.

Although a golfer, Mrs. Merrill's husband was also artistically inclined. A letter preserved at the house from his patient and former professor at Harvard, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. thanks Dr. Merrill for the gift of a hand-turned hub, presented as a token of Holmes's famous remark about Boston. Dr. Merrill crafted several of the picture frames in the house including one inscribed as being made of wood from the Boston Old Elm on the Common, "Boston's Oldest Inhabitant" as it was known until it blew down in a gale in 1876. The Merrills' younger daughter Ruth followed suit, graduating from the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Her thesis project, a self-portrait, still hangs in the house.

Now entering its third century, Parker House and its collections are sufficiently restored to have been included in a recent charity house tour. Illustrating close family ties to its grander neighbor, Barncastle, Parker House had on view memorabilia including scrapbooks, portraits and photographs belonging to Barncastle's builder, Effie Hinckley Kline,[14] founder of the Boston Ideal Opera Company and patron of the arts in Cleveland, and her husband Virgil, John D. Rockefeller's private lawyer,[15] friend and mentor of Charles W. Chesnutt and advisor to James A Garfield. Visitors were invited to examine the portrait collection to see if they could determine which pair, badly damaged by vandals in the 1940s, have received expert restoration in recent years.

See also

References

- ↑ Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Wikimapia - Let's describe the whole world!". wikimapia.org. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ Clough, Annie L. (1953). "Head of the Bay: Sketches and Pictures of Blue Hill, Maine 1762–1952". Blue Hill, Maine: Shoreacre Press.

- ↑ Shettleworth, Earle (2003). "John Calvin Stevens on the Portland Peninsula 1880 to 1940". Portland, Maine: Greater Portland Landmarks, Inc.

- ↑ "nativism: Definition from Answers.com". answers.com. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ "RootsWeb's WorldConnect Project: Blue Hill, Maine Founding Families". wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ Sargent, Emma Worcester (1923). "Epes Sargent of Gloucester and his Descendants". Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, p. 282.

- ↑ "Blue Hill Historical Society". bluehillhistory.org. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ Candage, R.G.F. (1905) "Historical Sketches of Bluehill, Maine". Ellsworth, Maine: Bluehill Historical Society.

- ↑ Brooks, Van Wyck (1940). "New England: Indian Summer, 1865–1915". Boston: E.P. Dutton & Co.

- ↑ "Maine Memory Network | Military enlistees, Blue Hill, 1864". mainememory.net. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ Baker, J.M. (2002). American House Styles: A Concise Guide. W.W. Norton. p. 117. ISBN 9780393323252. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ "Blue Hill Fair: Revisiting The Fair From 'Charlotte's Web' Sixty Years Later (PHOTOS)". huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ Yergin, Daniel (1991). "The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power". New York: Simon & Schuster.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||