Pareto principle

The Pareto principle (also known as the 80–20 rule, the law of the vital few, and the principle of factor sparsity)[1] states that, for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.[2] Management consultant Joseph M. Juran suggested the principle and named it after Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who, while at the University of Lausanne in 1896, published his first paper "Cours d'économie politique." Essentially, Pareto showed that approximately 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population; Pareto developed the principle by observing that 20% of the peapods in his garden contained 80% of the peas.[3]

It is a common rule of thumb in business; e.g., "80% of your sales come from 20% of your clients." Mathematically, the 80–20 rule is roughly followed by a power law distribution (also known as a Pareto distribution) for a particular set of parameters, and many natural phenomena have been shown empirically to exhibit such a distribution.[4]

The Pareto principle is only tangentially related to Pareto efficiency. Pareto developed both concepts in the context of the distribution of income and wealth among the population.

In economics

The original observation was in connection with population and wealth. Pareto noticed that 80% of Italy's land was owned by 20% of the population.[5] He then carried out surveys on a variety of other countries and found to his surprise that a similar distribution applied.

A chart that gave the inequality a very visible and comprehensible form, the so-called 'champagne glass' effect,[6] was contained in the 1992 United Nations Development Program Report, which showed the distribution of global income to be very uneven, with the richest 20% of the world's population controlling 82.7% of the world's income.[7]

| Quintile of population | Income |

|---|---|

| Richest 20% | 82.70% |

| Second 20% | 11.75% |

| Third 20% | 2.30% |

| Fourth 20% | 1.85% |

| Poorest 20% | 1.40% |

In science

The more unified a theory is, the more predictions it makes, and the greater the chance is of some of them being cheaply testable. Modifications of existing theories makes much fewer new and unique predictions, increasing the risk of the few there is all being very expensive to test.[9] If the Pareto principle or any other kind of increased costs were the cause of stagnation in the unification of especially physics, the modification of existing theories would have been even more severely slowed down than ever the unification by breakthroughs.[10] [11]

In business

The distribution is claimed to appear in several different aspects relevant to entrepreneurs and business managers. For example:

- 80% of a company's profits come from 20% of its customers

- 80% of a company's complaints come from 20% of its customers

- 80% of a company's profits come from 20% of the time its staff spend

- 80% of a company's sales come from 20% of its products

- 80% of a company's sales are made by 20% of its sales staff[12]

Therefore, many businesses have an easy access to dramatic improvements in profitability by focusing on the most effective areas and eliminating, ignoring, automating, delegating or retraining the rest, as appropriate.

In software

In computer science and engineering control theory, such as for electromechanical energy converters, the Pareto principle can be applied to optimization efforts.[13]

For example, Microsoft noted that by fixing the top 20% of the most-reported bugs, 80% of the related errors and crashes in a given system would be eliminated.[14]

In load testing, it is common practice to estimate that 80% of the traffic occurs during 20% of the time.

In software engineering, Lowell Arthur expressed a corollary principle: "20 percent of the code has 80 percent of the errors. Find them, fix them!"[15]

Occupational health and safety

The Pareto principle is used in occupational health and safety to underline the importance of hazard prioritization. Assuming 20% of the hazards will account for 80% of the injuries and by categorizing hazards, safety professionals can target those 20% of the hazards that cause 80% of the injuries or accidents. Alternatively, if hazards are addressed in random order, then a safety professional is more likely to fix one of the 80% of hazards which account for some fraction of the remaining 20% of injuries.[16]

Aside from ensuring efficient accident prevention practices, the Pareto principle also ensures hazards are addressed in an economical order as the technique ensures the resources used are best used to prevent the most accidents.[17]

Other applications

In the systems science discipline, Epstein and Axtell created an agent-based simulation model called SugarScape, from a decentralized modeling approach, based on individual behavior rules defined for each agent in the economy. Wealth distribution and Pareto's 80/20 principle became emergent in their results, which suggests the principle is a natural phenomenon.[18]

The Pareto principle has many applications in quality control. It is the basis for the Pareto chart, one of the key tools used in total quality control and six sigma. The Pareto principle serves as a baseline for ABC-analysis and XYZ-analysis, widely used in logistics and procurement for the purpose of optimizing stock of goods, as well as costs of keeping and replenishing that stock.[19]

The Pareto principle was also mentioned in the book 24/8 - The Secret for being Mega-Effective by Achieving More in Less Time by Amit Offir. Offir claims that if you want to function as a one-stop shop, simply focus on the 20% of what is important in a project and that way you will save a lot of time and energy.

In health care in the United States, 20% of patients have been found to use 80% of health care resources.[20]

Several criminology studies have found 80% of crimes are committed by 20% of criminals.This statistic is used to support both stop-and-frisk policies and broken windows policing, as catching those criminals committing minor crimes will likely net many criminals wanted for (or who would normally commit) larger ones.

In the financial services industry, this concept is known as profit risk, where 20% or fewer of a company's customers are generating positive income, while 80% or more are costing the company money.[21]

Mathematical notes

The idea has rule of thumb application in many places, but it is commonly misused. For example, it is a misuse to state a solution to a problem "fits the 80–20 rule" just because it fits 80% of the cases; it must also be that the solution requires only 20% of the resources that would be needed to solve all cases. Additionally, it is a misuse of the 80–20 rule to interpret data with a small number of categories or observations.

This is a special case of the wider phenomenon of Pareto distributions. If the Pareto index α, which is one of the parameters characterizing a Pareto distribution, is chosen as α = log45 ≈ 1.16, then one has 80% of effects coming from 20% of causes.

It follows that one also has 80% of that top 80% of effects coming from 20% of that top 20% of causes, and so on. Eighty percent of 80% is 64%; 20% of 20% is 4%, so this implies a "64-4" law; and similarly implies a "51.2-0.8" law. Similarly for the bottom 80% of causes and bottom 20% of effects, the bottom 80% of the bottom 80% only cause 20% of the remaining 20%. This is broadly in line with the world population/wealth table above, where the bottom 60% of the people own 5.5% of the wealth.

The 64-4 correlation also implies a 32% 'fair' area between the 4% and 64%, where the lower 80% of the top 20% (16%) and upper 20% of the bottom 80% (also 16%) relates to the corresponding lower top and upper bottom of effects (32%). This is also broadly in line with the world population table above, where the second 20% control 12% of the wealth, and the bottom of the top 20% (presumably) control 16% of the wealth.

The term 80–20 is only a shorthand for the general principle at work. In individual cases, the distribution could just as well be, say, 80–10 or 80–30. There is no need for the two numbers to add up to the number 100, as they are measures of different things, e.g., 'number of customers' vs 'amount spent'). However, each case in which they do not add up to 100%, is equivalent to one in which they do; for example, as noted above, the "64-4 law" (in which the two numbers do not add up to 100%) is equivalent to the "80–20 law" (in which they do add up to 100%). Thus, specifying two percentages independently does not lead to a broader class of distributions than what one gets by specifying the larger one and letting the smaller one be its complement relative to 100%. Thus, there is only one degree of freedom in the choice of that parameter.

Adding up to 100 leads to a nice symmetry. For example, if 80% of effects come from the top 20% of sources, then the remaining 20% of effects come from the lower 80% of sources. This is called the "joint ratio", and can be used to measure the degree of imbalance: a joint ratio of 96:4 is very imbalanced, 80:20 is significantly imbalanced (Gini index: 60%), 70:30 is moderately imbalanced (Gini index: 40%), and 55:45 is just slightly imbalanced.

The Pareto principle is an illustration of a "power law" relationship, which also occurs in phenomena such as brush fires and earthquakes.[22] Because it is self-similar over a wide range of magnitudes, it produces outcomes completely different from Gaussian distribution phenomena. This fact explains the frequent breakdowns of sophisticated financial instruments, which are modeled on the assumption that a Gaussian relationship is appropriate to, for example, stock price movements.[23]

Equality measures

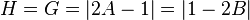

Gini coefficient and Hoover index

Using the "A : B" notation (for example, 0.8:0.2) and with A + B = 1, inequality measures like the Gini index (G) and the Hoover index (H) can be computed. In this case both are the same.

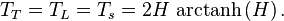

Theil index

The Theil index is an entropy measure used to quantify inequalities. The measure is 0 for 50:50 distributions and reaches 1 at a Pareto distribution of 82:18. Higher inequalities yield Theil indices above 1.[24]

See also

- 1% rule (Internet culture)

- 10/90 gap

- Benford's law

- Diminishing returns

- Elephant flow

- Long tail

- Mathematical economics

- Megadiverse countries

- Ninety-ninety rule

- Pareto distribution

- Pareto priority index

- Parkinson's law

- Price's law

- Principle of least effort

- Profit risk

- Rank-size distribution

- Sturgeon's law

- Vitality curve

- Wealth concentration

- Zipf's law

References

- ↑ THE APPLICATION OF THE PARETO PRINCIPLE IN SOFTWARE ENGINEERING. Ankunda R. Kiremire 19th October, 2011

- ↑ Bunkley, Nick (March 3, 2008), "Joseph Juran, 103, Pioneer in Quality Control, Dies", New York Times

- ↑ "What is 80/20 rule?". 80/20 Rule of Presenting Ideas. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ↑ Newman, MEJ. "Power laws, Pareto Distributions, and Zipf's law" (PDF). p. 11. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ↑ Pareto, Vilfredo; Page, Alfred N. (1971), Translation of Manuale di economia politica ("Manual of political economy"), A.M. Kelley, ISBN 978-0-678-00881-2

- ↑ Gorostiaga, Xabier (January 27, 1995), "World has become a 'champagne glass' globalisation will fill it fuller for a wealthy few", National Catholic Reporter

- ↑ United Nations Development Program (1992), 1992 Human Development Report, New York: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Human Development Report 1992, Chapter 3, retrieved 2007-07-08

- ↑ "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" 1877–1878, Charles Sanders Peirce

- ↑ "Karl Popper (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy/Spring 2013 Edition)". Plato.stanford.edu.

- ↑ All Life is Problem Solving, Karl Popper

- ↑ Living Life the 80/20 Way by Richard Koch

- ↑ Gen, M.; Cheng, R. (2002), Genetic Algorithms and Engineering Optimization, New York: Wiley

- ↑ Rooney, Paula (October 3, 2002), Microsoft's CEO: 80–20 Rule Applies To Bugs, Not Just Features, ChannelWeb

- ↑ Pressman, Roger S. (2010). Software Engineering: A Practitioner's Approach (7th ed.). Boston, Mass: McGraw-Hill, 2010. ISBN 978–0–07–337597–7.

- ↑ Woodcock, Kathryn (2010). Safety Evaluation Techniques. Toronto, ON: Ryerson University. p. 86.

- ↑ "Introduction to Risk-based Decision. Making" (PDF). USCG Safety Program. United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Epstein, Joshua; Axtell, Robert (1996), Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom-Up, MIT Press, p. 208, ISBN 0-262-55025-3

- ↑ Rushton, Oxley & Croucher (2000), pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Myrl Weinberg: In health-care reform, the 20-80 solution | Contributors | projo.com | The Providence Journal

- ↑ Profit Risk

- ↑ Bak, Per (1999), How Nature Works: the science of self-organized criticality, Springer, p. 89, ISBN 0-387-94791-4

- ↑ Taleb, Nassim (2007), The Black Swan, pp. 229–252, 274–285

- ↑ On Line Calculator: Inequality

Further reading

- Bookstein, Abraham (1990), "Informetric distributions, part I: Unified overview", Journal of the American Society for Information Science 41 (5): 368–375, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199007)41:5<368::AID-ASI8>3.0.CO;2-C

- Klass, O. S.; Biham, O.; Levy, M.; Malcai, O.; Soloman, S. (2006), "The Forbes 400 and the Pareto wealth distribution", Economics Letters 90 (2): 290–295, doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2005.08.020 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Koch, R. (2001), The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More with Less, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing

- Koch, R. (2004), Living the 80/20 Way: Work Less, Worry Less, Succeed More, Enjoy More, London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, ISBN 1-85788-331-4

- Reed, W. J. (2001), "The Pareto, Zipf and other power laws", Economics Letters 74 (1): 15–19, doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(01)00524-9

- Rosen, K. T.; Resnick, M. (1980), "The size distribution of cities: an examination of the Pareto law and primacy", Journal of Urban Economics 8 (2): 165–186, doi:10.1016/0094-1190(80)90043-1 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Rushton, A.; Oxley, J.; Croucher, P. (2000), The handbook of logistics and distribution management (2nd ed.), London: Kogan Page, ISBN 978-0-7494-3365-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pareto principle. |