Papist

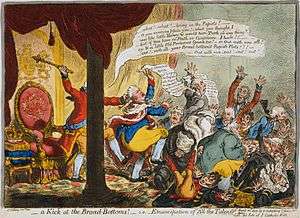

Papist is a sectarian term referring to the Roman Catholic Church, its teachings, practices, or adherents. It is usually understood as a disparaging term.[2] The word gained currency during the English Reformation, as it was used to denote a person whose loyalties were to the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church, rather than to the Church of England. Attested from 1534, papist derives (through Middle French) from Latin papa, meaning "Pope".[3]

Description

The word was in common use by Protestant writers until the mid-nineteenth century, as shown by its frequent appearance in Thomas Macaulay's History of England from the Accession of James II and in other works of that period, including those with no sectarian bias. It also appeared in the compound form "Crypto-Papist", referring to members of Reformed, Protestant, or nonconformist churches who at heart were allegedly Roman Catholics.[4][5][6]

The word is found in certain surviving statutes of the United Kingdom, for example in the English Bill of Rights of 1688 and the Scottish Claim of Right of 1689. Under the Act of Settlement of 1701, no one who professes "the popish religion" or marries "a papist" may succeed to the throne of the United Kingdom. Fears that Roman Catholic secular leaders would be anti-Protestant arose after the Roman Catholic Church was banned in England in the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), author of Gulliver's Travels, employed the term throughout his satirical A Modest Proposal, in which he proposed selling Irish babies to be eaten by wealthy English landlords.

Similar terms, "papalism" and "popery", are sometimes used,[7][8][9] as in the Popery Act 1698 and the Irish Popery Act. The Seventh-day Adventist prophetess Ellen G. White uses the terms "papist" and "popery" throughout her book The Great Controversy, a volume harshly criticized for its anti-Catholic tone.

During the 1928 American presidential election, Democratic Party nominee Al Smith was labeled a "papist" by his political opponents. He was the first Roman Catholic ever to gain the presidential nomination of a major party, and this led to fears that, if he were elected, the United States government would follow the dictates of the Vatican.[10] As of 2015, John F. Kennedy is the only Roman Catholic to be elected President of the United States.

The term is still used by some today,[11][12] although not as frequently as in previous eras.

See also

References

- ↑ Bulut, Mehmet (2001). Ottoman-Dutch economic relations in the early modern period 1571-1699. Uitgeverij Verloren. p. 112. ISBN 978-90-6550-655-9.

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/papist

- ↑ papist, Merriam Webster Online

- ↑ Walter Walsh, The Secret History of the Oxford Movement (C.J. Thynnes, 1898), pp. 8 and 187

- ↑ The American National Preacher, August 1851, Sermon DLIII, p. 190

- ↑ Alexis Khomiakhov, a Russian lay theologian of the nineteenth century, wrote, "All Protestants are Crypto-Papists" (James J. Stamoolis (2004). Brad Nassif, ed. Three views on Eastern Orthodoxy and evangelicalism. Zondervan. p. 20. ISBN 0310235391.).

- ↑ Dr J. J. Overbeck and His Scheme for the Re-establishment of the Orthodox Church in the West

- ↑ http://www.thefreedictionary.com/popery

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/popery

- ↑ Michael O'Brien, John F. Kennedy: A Biography, Thomas Dunne Books, 2005, p. 414.

- ↑ Vladimir Moss, Letter to a Papist

- ↑ Ian Paisley, Papist Doctrine of Oaths