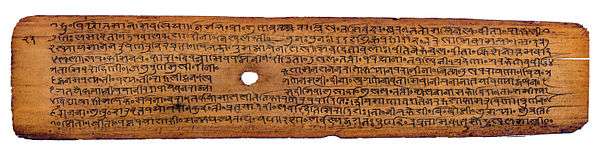

Palm-leaf manuscript

_Manuscript_LACMA_M.88.134.4_(1_of_2).jpg)

Palm-leaf manuscripts (Talapatra grandham) are manuscripts made out of dried palm leaves. Palm leaves were used as writing materials in South Asia and in Southeast Asia dating back to the 5th century BCE,[1] and possibly much earlier.[2] Their use began in South Asia, and spread elsewhere, as texts on dried and smoke treated palm leaves of Borassus species (Palmyra palm) or the ola leaf (leaf of the Corypha umbraculifera or Talipot palm).[2]

One of the oldest surviving palm leaf manuscript is a Sanskrit Shaivism text from the 9th-century, discovered in Nepal, now preserved at the Cambridge University Library.[3]

History

Palm leaf manuscripts were written in ink on rectangular cut and cured palm leaf sheet. Each sheet typically had a hole through which a string could pass through, and with these the sheets were tied together with a string to bind like a book. A palm leaf text thus created had a limited time (between few decades to ~600 years) and the document had to be copied onto new sets of dried palm leaves as the document decayed due to dampness, insect activity, mold and fragility.[2]

The oldest surviving palm leaf Indian manuscripts have been found in colder, drier climates such as in parts of Nepal, Tibet and central Asia, the source of 1st-millennium CE manuscripts.[4] The individual sheets of palm leaves were called Patra or Parna in Sanskrit (Pali/Prakrit: Panna), and the medium when ready to write was called Tada-patra (or Tala-patra, Tali, Tadi).[4] The famous 5th-century CE Indian manuscript called the Bower Manuscript discovered in Chinese Turkestan, was written on birch-bark sheets shaped in the form of treated palm leaves.[4]

John Guy and Jorrit Britschgi state Hindu temples served as centers where ancient manuscripts were routinely used for learning and where the texts were copied when they wore out.[5] In South India, temples and associated mutts served custodial functions, and a large number of manuscripts on Hindu philosophy, poetry, grammar and other subjects were written, multiplied and preserved inside the temples.[6] Archaeological and epigraphical evidence indicates existence of libraries called Sarasvati-bhandara, dated possibly to early 12th-century and employing librarians, attached to Hindu temples.[7] Palm leaf manuscripts were also preserved inside Jain temples and in Buddhist monasteries.

With the spread of Indian culture to Southeast Asian countries like as Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines, these nations also became home to large collections. Palm-leaf manuscripts called Lontar in dedicated stone libraries have been discovered by archaeologists at Hindu temples in Bali Indonesia and in 10th century Cambodian temples such as Angkor Wat and Banteay Srei.[8]

One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit manuscripts on palm leaves is of the Parameshvaratantra, a Shaiva Siddhanta text of Hinduism. It is from the 9th-century, and dated to about 828 CE.[3] The discovered palm-leaf collection also includes a few parts of another text, the Jñānārṇavamahātantra and currently held by the University of Cambridge.[3]

With the introduction of printing presses in the early 19th century, this cycle of copying from palm leaves came to an end. Many governments are making efforts to preserve what is left of their palm leaf documents.[9][10][11]

Impact on the design of regional alphabet scripts

The rounded or diagonal shapes of the letters of many of the scripts of South India and Southeast Asia, such as Devanagari, Nandinagari, Telugu script, Lontara, the Javanese script, the Balinese alphabet, the Odia alphabet, the Burmese alphabet, the Tamil script and others may have developed as an adaptation to writing on palm leaves, as angular letters tend to split the leaf.[12]

Regional variations

Burmese

Odisha

Palm leaf manuscripts of Odisha include scriptures, pictures of Devadasi and various mudras of the Kama Sutra. Some of the early discoveries of Odia palm leaf manuscripts include writings like Smaradipika, Ratimanjari, Pancasayaka and Anangaranga in both Odia and Sanskrit.[13] State Museum of Odisha at Bhubaneswar houses 40,000 palm leaf manuscripts.Most of them are written in the Odia script, though the language is Sanskrit. The oldest manuscript here belongs to the 14th century but the text can be dated to the 2nd century.[14]

Tamil Nadu

In 1997 The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) recognised the Tamil Medical Manuscript Collection as part of the Memory of the World Register. A very good example of usage of palm leaf manuscripts to store the history is a Tamil grammar book named Tolkāppiyam which was written c. 4th century. A global digitalization project led by the Tamil Heritage Foundation collects, preserves, digitizes and makes ancient palm-leaf manuscript documents available to users via the internet.[15]

Javanese and Balinese

In Indonesia the palm-leaf manuscript is called lontar. The Indonesian word is the modern form of Old Javanese rontal. It is composed of two Old Javanese words, namely ron "leaf" and tal "Borassus flabellifer, palmyra palm". Due to the shape of the palmyra palm's leaves, which are spread like a fan, these trees are also known as "fan trees". The leaves of the rontal tree have always been used for many purposes, such as for the making of plaited mats, palm sugar wrappers, water scoops, ornaments, ritual tools, and writing material. Today, the art of writing in rontal still survive in Bali, performed by Balinese Brahmin as sacred duty to rewrite Hindu texts.

Many old manuscripts dated from ancient Java, Indonesia, were written on rontal palm-leaf manuscript. Manuscripts dated from 14th to 15th century Majapahit period, or even earlier, such as the Arjunawiwaha, the Smaradahana, the Nagarakretagama and the Kakawin Sutasoma, were discovered on the neighboring islands of Bali and Lombok. This suggested that the tradition of preserving, copying and rewriting palm-leaf manuscripts continued for centuries. Other palm-leaf manuscripts include Sundanese language works: the Carita Parahyangan, the Sanghyang siksakanda ng karesian and the Bujangga Manik.

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.cedar.buffalo.edu/~zshi/Papers/kbcs04_261.pdf

- 1 2 3 "Literature | The Story of India - Photo Gallery". PBS. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- 1 2 3 Pārameśvaratantra (MS Add.1049.1) with images, Puṣkarapārameśvaratantra, University of Cambridge (2015)

- 1 2 3 Amalananda Ghosh (1991), An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004092648, pages 360-361

- ↑ John Guy and Jorrit Britschgi (2011), Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India, 1100-1900, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 978-1588394309, page 19

- ↑ Saraju Rath (2012), Aspects of Manuscript Culture in South India, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004219007, pages ix, 158-168, 252-259

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), From Temple schools to Universities, in Handbook of Oriental Studies, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 183-186

- ↑ Wayne A. Wiegand and Donald Davis (1994), Encyclopedia of Library History, Routledge, ISBN 978-0824057879, page 350

- ↑ "Conservation and Digitisation of Rolled Palm Leaf Manuscripts in Nepal". Asianart.com. 2005-11-14. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ 論述貝葉經整理與編目工作

- ↑ "Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts". Laomanuscripts.net. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ↑ Sanford Steever, 'Tamil Writing'; Kuipers & McDermott, 'Insular Southeast Asian Scripts', in Daniels & Bright, The World's Writing Systems, 1996, p. 426, 480

- ↑ Nāgārjuna Siddha (2002). Conjugal Love in India: Ratiśāstra and Ratiramaṇa : Text, Translation, and Notes. BRILL. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-90-04-12598-8. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/ancient-palm-leaf-manuscripts-are-in-danger-of-crumbling-away/1/265760.html

- ↑ Interview: Digitalizing heritage for the coming generation. Bhasha India. Microsoft. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

External links

![]() Media related to Palm-leaf manuscripts at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Palm-leaf manuscripts at Wikimedia Commons