Pall Mall, London

| |

|---|---|

Pall Mall in 2009 | |

| Length | 0.3 mi (0.5 km) |

| Location | Westminster, London, UK |

| East end | Haymarket |

| West end | St James's Street |

| Construction | |

| Commissioned | July 1661 |

| Inauguration | September 1661 |

| Other | |

| Known for | gentlemen's clubs · Monopoly |

Pall Mall /ˌpæl ˈmæl/ is a street in the City of Westminster in London, parallel to The Mall, stretching from St James's Street across Waterloo Place to the Haymarket. Pall Mall East continues to Trafalgar Square. The street is a major thoroughfare in the St James's area of London, and a section of the regional A4 road. The street's name is derived from "pall-mall", a ball game that was played there during the 17th century.

History and topography

Early history and pall-mall field

Pall Mall was built in 1661, replacing an earlier highway slightly to the south that ran from the Haymarket (approximately where Warwick House Street is now) to the royal residence, St James's Palace.[1] Evidence suggests a road had been in this location since Saxon times, although the earliest documentary references are from the 12th century in connection with St James's Hospital, a leper colony. When St James's Park was laid by order of Henry VIII in the 16th century, the park's boundary wall was built along the south side of the road.[lower-alpha 1] In 1620, the Privy Council ordered the High Sheriff of Middlesex to clear "divers base sheddes and tentes sett up under St. James Park wall betweene Charinge Chrosse and St. James House, ... whiche are all offensive and noe way fitt to be suffered to stand."[2]

Pall-mall, a ball game similar to croquet, was introduced to England in the early-17th century by James I. The game, already popular in France and Scotland, was enjoyed by James' sons Henry and Charles.[3] In 1630, St James's Field, London's first pall-mall court, was laid out to the north of the Haymarket - St James road. Archibald Lumsden received a grant in September 1635 "for sole furnishing of all the malls, bowls, scoops, and other necessaries for the game of Pall Mall within his grounds in St. James's Fields and that such as resort there shall pay him such sums of money as are according to the ancient order of the game."[4]

After the Restoration and King Charles II's return to London on 29 May 1660, a pall-mall court was constructed in St James's Park just south of the wall, on the site of The Mall.[2] Samuel Pepys's diary entry for 2 April 1661 records that he "... went into St. James's Park, where I saw the Duke of York playing at Pelemele, the first time that I ever saw the sport."[5] This new court suffered from dust blown over the wall from coaches travelling along the highway, which was "... very troublsom to the players at Mall." Accordingly, in July 1661 posts and rails were erected "to barre up the old way".[2] The court for pall-mall was very long and narrow, and often known as an alley, so the old court provided a suitable route for relocating the eastern approach to St James's Palace. A grant was made to Dan O'Neale, Groom of the Bedchamber, and John Denham, Surveyor of the King's Works "of a piece of ground 1,400 feet in length and twenty-three in breadth, between St. James's Park and Pall Mall." The grant was endorsed "Our warrant for the building of the new street to St James's."[4]

A new road was built on the site of the old pall-mall court, and opened to in September 1661.[2] It was officially named Catherine Street, after Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II, but was better known as Pall Mall Street or the Old Pall Mall.[4][6][lower-alpha 2]

17th- and 18th-century buildings

In 1662 Pall Mall was one of several streets "thought fitt immediately to be repaired, new paved or otherwise amended" under the Streets, London and Westminster Act 1662.[10] The paving commissioners appointed to oversee the work included the Earl of St Albans. The terms of the act allowed the commissioners to remove any building encroaching on the highway, with compensation for those at least 30 years old. The commissioners determined that the real tennis court and adjoining house at the northeast corner of Pall Mall and St James's Street should be demolished, and in 1664 notified Martha Barker, the owner of the Crown lease, that they "thought fitt to have it taken down to enlarge the said way". Barker initially rejected the £230 offered in compensation, but must have acquiesced, as the court was demolished by 1679.[2]

During the period 1662–1667, the street was developed extensively. The Earl of St Albans had received a lease from the Crown in 1662 on 45 acres of land that was formerly St James's Fields. Soon afterwards the earl began to lay out the site for the development of St James's Square, Jermyn Street, Charles Street, St Albans Street, King Street and the other streets now known as St James's. The location was convenient for the royal palaces of Whitehall and St James and the houses on the east, north and west sides of the square were developed along with those on the north side of Pall Mall, each house was constructed separately as was usual at that time. At first houses were not built along the south side of St James's Square, or the adjoining portion of Pall Mall. The earl petitioned the king in late 1663 that the class of occupants they hoped to attract to the new district would not take houses without the prospect of eventually acquiring them outright. Despite opposition from the Lord Treasurer, the Earl of Southampton, on 1 April 1665 the king granted the Earl of St Albans the freehold of the St James's Square site, along with all the ground on the north side of Pall Mall between St James's Street and the east side of St James's Square. The freehold of the north side of Pall Mall subsequently passed to other private owners.[2]

The Crown kept the freehold of all the land south of the street except for No. 79, which was granted by Charles II to Nell Gwynne's trustees in 1676 or 1677. The buildings constructed on the south side of Pall Mall in subsequent years were grander than those on the north owing to stricter design and building standards imposed by the Crown commissioners.[2]

When the road alignment moved to the north, several houses built to face south onto the eastern end of the highway in the 1650s now backed north onto the new street. In 1664, their tenants petitioned the king that their houses had been "... built applicable to it [the original road] and cannot be turned without great damage and charge." As compensation, they asked to be given the site of the old road "... to augment their gardens ..." Their request was successful and the trustees of the Earl of St Albans received a sixty-year lease on most of the former highway from April 1665 so that the trustees could issue sub-leases to their tenants.[2]

Several other portions of the old highway were leased for construction. At the east end land was leased to Sir Philip Warwick, who built Warwick House (where Warwick House Street is now) and to Sir John Denham, this parcel became part of the grounds of Marlborough House. Portions leased at the west end included the land between St James's Palace and the tennis court at the corner of St James's Street, and a parcel of land leased to the Duchess of Cleveland that became the site of 8–12 Cleveland Row and Stornoway House.[2]

Later history

By the 18th century, Pall Mall was well known for its shops as well as its grand houses. The shops included that of the Vulliamy family who made clocks at No. 68 between 1765 and 1854. Robert Dodsley ran a bookshop at No. 52, where he suggested the ideal of a dictionary to Samuel Johnson. Writers and artists began to move to Pall Mall during this century; both Richard Cosway and Thomas Gainsborough lived at Schomberg House at Nos. 80-82.[11]

The street was one of the first in London to be lit by gas after F.A. Winsor set up experimental lighting on 4 June 1807 to celebrate King George III's birthday. Permanent lighting was installed in 1820.[11] The eastern end of Pall Mall was widened between 1814 and 1818; a row of houses on its north side was demolished to make way for the Royal Opera Arcade.[2]

Pall Mall is known for the various gentlemen's clubs built there in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Travellers Club was founded in 1819 and moved to No. 49 Pall Mall in 1822. Its current premises at No. 106 was built in 1823 by Charles Barry.[12] The Athenaeum Club took its name from the Athenaeum in Rome, a university founded by the Emperor Hadrian. The club moved to No. 107 Pall Mall in 1830 from tenements in Somerset House. Its entrance hall was designed by Decimus Burton.[13] The Reform Club at Nos. 104-105 was founded for the British Radicals in 1836.[14] The Army and Navy Club at Nos. 36-39 was founded in 1837. The name was suggested by the Duke of Wellington in order to accommodate Royal Navy members.[15] Other clubs on Pall Mall include the United Service Club (now occupied by the Institute of Directors), the Oxford and Cambridge Club and the Royal Automobile Club.[11]

Pall Mall was once the centre of London's fine art scene; in 1814 the Royal Academy, the National Gallery and Christie's auction house were all based on the street.[16]

The freehold of nearly all of the southern side of the Pall Mall is still owned by the Crown Estate. St. James's Palace is on the south side of the street at the western end. Marlborough House, which was once a royal residence, is its neighbour to the east, opening off a courtyard just to the south of the street. The Prince Regent's Carlton House once stood at the eastern end. Pall Mall was the location of the War Office, with which it became synonymous (just as Whitehall refers to the administrative centre of the UK government). The War Office was accommodated in a complex of buildings based on the ducal mansion, Cumberland House, which was designed by Matthew Brettingham and Robert Adam.

The street contained two other architecturally important ducal residences, Schomberg House, and Buckingham House, the London residence of the Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos which was rebuilt for them by Sir John Soane (not to be confused with the Buckingham House which became Buckingham Palace). Buckingham House was demolished in 1908 to make way for the Royal Automobile Club.

The former branch of the Midland Bank in Pall Mall was designed by Edwin Lutyens.

Popular culture

Pall Mall is also one of the streets on the UK version of the Monopoly board.

Notable buildings

- St James's Palace

- No. 36 – Army and Navy Club [17]

- No. 59 – Quebec Government Office in London [18]

- No. 71 – Oxford and Cambridge Club [19]

- No. 80 – Schomberg House

- No. 89 – Royal Automobile Club [20]

- No. 100 – Embassy of Kosovo [21]

- No. 104 – Reform Club [22]

- No. 106 – Travellers Club [23]

- No. 107 – Athenaeum Club [24]

- No. 116 – Institute of Directors [25]

- No. 125 – Embassy of Kazakhstan [26]

Street numbering

The street numbers run consecutively from north-side east to west and then continue on the south-side west to east.

Comparisons in Literature

When William Makepeace Thackeray visited Dublin in 1845, he compared Pall Mall to O'Connell Street, then known as Upper Sackville Street, with: "The street is exceedingly broad and handsome; the shops at the commencement, rich and spacious; but in Upper Sackville Street, which closes with the pretty building and gardens of the Rotunda, the appearance of wealth begins to fade somewhat, and the houses look as if they had seen better days. Even in this, the great street of the town, there is scarcely any one, and it is as vacant and listless as Pall Mall in October."[27]

See also

- List of London's gentlemen's clubs

- The Diogenes Club, a fictional club located in Pall Mall

References

Notes

- ↑ In 1685, the boundary wall became the parish boundary for the parish of Westminster St James.

- ↑ By 9 August 1662, Pepys's diary reports a duel "... at the old Pall Mall at St. James's ..." in which Thomas Jermyn (nephew of the Earl of St Albans) was wounded and Colonel Giles Rawlins was killed.[7] On 15 May 1663, he "... walked in the Parke, discoursing with the keeper of the Pell Mell, who was sweeping of it; who told me of what the earth is mixed that do floor the Mall, and that over all there is cockle-shells powdered, and spread to keep it fast; which, however, in dry weather, turns to dust and deads the ball."[8] The pall-mall field was a popular place for recreation at this time and Pepys records several other visits. By July 1665 Pepys used "Pell Mell" to refer to the street as well as the game: "Walked round to White Hall, the Park being quite locked up; and I observed a house shut up this day in the Pell Mell, where heretofore in Cromwell's time we young men used to keep our weekly clubs."[9]

Citations

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 619-620.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 F. H. W. Sheppard (General Editor) (1960). "Pall Mall". Survey of London: volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster, Part 1. Institute of Historical Research. p. 322–324. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 619.

- 1 2 3 Wheatley, Henry Benjamin (1870). Round about Piccadilly and Pall Mall. p. 319.

- ↑ Pepys, Samuel (2 April 1661). "March 1st". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

- ↑ F. H. W. Sheppard (General Editor) (1960). "Piccadilly, South Side". Survey of London: volumes 29 and 30: St James Westminster, Part 1. Institute of Historical Research. p. 251–270. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ Pepys, Samuel (9 August 1662). "August 9th". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

- ↑ Pepys, Samuel (15 May 1663). "May 15th". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

- ↑ Pepys, Samuel (4 July 1665). "July 4th". Diary of Samuel Pepys. ISBN 0-520-22167-2.

- ↑ John Raithby, ed. (1819), "Streets, London and Westminster Act 1662", Statutes of the Realm: Volume 5: 1628–80, pp. 351–357, retrieved 5 July 2013

- 1 2 3 Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 620.

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 944-5.

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 685.

- ↑ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 27.

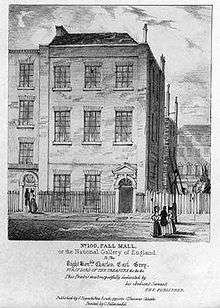

- ↑ "Illustration of building facades along the street in 1814 (297k GIF format)". Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- ↑ "Army and Navy Club website". 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Québec Government website". 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Oxford and Cambridge Club website". 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Royal Automobile Club website". 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "The London Diplomatic List" (PDF). 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Reform Club website". 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Travellers Club website". 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Athenaeum Club website". 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "Institute of Directors website". 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "The London Diplomatic List" (PDF). 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Thackeray, W. M. (1846). An Irish Sketch Book. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

Sources

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2008). The London Encyclopedia. Pan McMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

Further reading

- John Timbs (1867), "Pall Mall", Curiosities of London (2nd ed.), London: J.C. Hotten, OCLC 12878129

- Charles Dickens (1882), "Pall Mall", Dickens's Dictionary of London, London: Macmillan & Co.

External links

- Introductory page from the Survey of London – see also here for the Survey of London's chapters on each of the principal buildings in the street, and here for its diagrams showing the north and south sides in 1814 and the south side in 1960.

- Pall Mall on TourUK

- Panoramic photograph of Pall Mall

- 19th Century Gentleman's Clubs on Pall Mall (including photographs)

- The Institute of Directors' 116 Pall Mall

Coordinates: 51°30′25″N 0°07′59″W / 51.50694°N 0.13306°W