Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

| Paleo-Hebrew alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Hebrew |

Time period | 10th century BCE – 135 CE |

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

Child systems | Samaritan alphabet |

| U+10900–U+1091F | |

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

|

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet (Hebrew: הכתב העברי הקדום), also spelt Palaeo-Hebrew alphabet, is a variant of the Phoenician alphabet.[1] Like the Phoenician alphabet, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet contains 22 letters, all of which are consonants, and is described as an abjad. The term was coined by Solomon Birnbaum in 1954 who wrote "To apply the term Phoenician to the script of the Hebrews is hardly suitable".[2] Even so, the script is nearly identical to the Phoenician script.

Archeological evidence of the use of the script by the Israelites for writing the Hebrew language dates to around the 10th century BCE. The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet began to fall out of use by the Jews in the 5th century BCE when the Aramaic alphabet was adopted as the predominant writing system for Hebrew, from which the present Jewish "square-script" Hebrew alphabet evolved. The Samaritans, who now number less than one thousand people, have continued to use a derivative of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, known as the Samaritan alphabet.

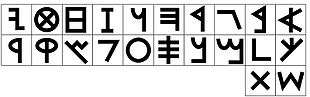

Letters

The chart below compares the letters of the Phoenician script with those of the Paleo-Hebrew and the present Hebrew alphabet, with names traditionally used in English.

| Phoenician | Paleo-Hebrew | Hebrew letter (Dfus) | English name |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

א | Aleph |

| |

|

ב | Bet |

| |

|

ג | Gimel |

| |

|

ד | Dalet |

| |

|

ה | He |

| |

|

ו | Waw |

| |

|

ז | Zayin |

| |

|

ח | Heth |

| |

|

ט | Teth |

| |

|

י | Yodh |

| |

|

כ/ך | Kaph |

| |

|

ל | Lamedh |

| |

|

מ/ם | Mem |

| |

|

נ/ן | Nun |

| |

|

ס | Samekh |

| |

|

ע | Ayin |

| |

פ/ף | Pe | |

| |

|

צ/ץ | Tsade |

| |

|

ק | Qoph |

| |

|

ר | Resh |

| |

|

ש | Shin |

| |

|

ת | Taw |

History

According to contemporary scholars, the Paleo-Hebrew script developed alongside others in the region during the course of the late second and first millennia BCE. It is closely related to the Phoenician script.

The earliest known inscription in the Paleo-Hebrew script was the Zayit Stone discovered on a wall at Tel Zayit, in the Beth Guvrin Valley in the lowlands of ancient Judea.[3] The 22 letters were carved on one side of the 38 lb (17 kg) stone - which resembles a bowl on the other. The find is attributed to the mid-10th century BCE.

The script of the Gezer calendar,[4][5] dated to the late 10th century BCE, bears strong resemblance to contemporaneous Phoenician script from inscriptions at Byblos.

Clear Hebrew features are visible in the scripts of the Moabite inscriptions of the Mesha Stele, set up around 840 BCE by King Mesha of Moab.[6] Similarly, the Tel Dan Stele from approximately 810 BCE resembles Hebrew inscriptions although its writing is classified as Old Aramaic and it dates from a period when Dan had already fallen into the orbit of Damascus.

The 8th-century Hebrew inscriptions exhibit many specific and exclusive traits, leading modern scholars to conclude that already in the 10th century BCE the Paleo-Hebrew script was used by wide scribal circles.

Even though very few 10th-century Hebrew inscriptions have been found, the quantity of the epigraphic material from the 8th century onward shows the gradual spread of literacy among the people of the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah.

In 1855 a Phoenician inscription in 22 lines was found among the ruins of Sidon. Each line contained about 40 or 50 characters. A facsimile copy of the writing was published in United States Magazine in July 1855. The inscription was on the lid of a large stone sarcophagus carved in fine Egyptian style. The writing was primarily a genealogical history of a king of Sidon buried in the sarcophagus.[7]

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was in common use in the ancient Israelite kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Following the exile of the Kingdom of Judah in the 6th century BCE, in the Babylonian exile, Jews began using a form of the Assyrian script, which was another offshoot of the same family of scripts. The Samaritans, who remained in the Land of Israel, continued to use the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet.

During the 3rd century BCE, Jews began to use a stylized, "square" form of the Aramaic alphabet that was used by the Persian Empire (which in turn was adopted from the Assyrians),[8] while the Samaritans continued to use a form of the Paleo-Hebrew script, called the Samaritan script. After the fall of the Persian Empire, Jews used both scripts before settling on the Assyrian form. For a limited time thereafter, the use of the Paleo-Hebrew script among Jews was retained only to write the Tetragrammaton.[9]

Further development

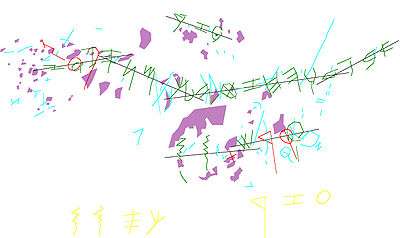

The independent Hebrew script evolved by developing numerous cursive features, the lapidary features of the Phoenician alphabet being ever less pronounced with the passage of time. The aversion of the lapidary script may indicate that the custom of erecting stelae by the kings and offering votive inscriptions to the deity was not widespread in Israel. Even the engraved inscriptions from the 8th century exhibit elements of the cursive style, such as the shading, which is a natural feature of pen-and-ink writing. Examples of such inscriptions include the Siloam inscription,[10] numerous tomb inscriptions from Jerusalem,[11][12] the Ketef Hinnom amulets, a fragmentary Hebrew inscription on an ivory which was taken as war spoils (probably from Samaria) to Nimrud, and the hundreds of 8th to 6th-century Hebrew seals from various sites. The most developed cursive script is found on the 18 Lachish ostraca,[13] letters sent by an officer to the governor of Lachish just before the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE. A slightly earlier (circa 620 BCE) but similar script is found on an ostracon excavated at Mesad Hashavyahu, containing a petition for redress of grievances (an appeal by a field worker to the fortress's governor regarding the confiscation of his cloak, which the writer considers to have been unjust).[14][15]

Decline of use

After the Babylonian capture of Judea, when most of the nobles were taken into exile, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet continued to be used by the people who remained. One example of such writings are the 6th-century BCE jar handles from Gibeon, on which the names of winegrowers are inscribed. Beginning from the 5th century BCE onward, when the Aramaic language and script became an official means of communication, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was preserved mainly for writing the Tanakh by a coterie of erudite scribes. Some Paleo-Hebrew fragments of the Torah were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls: manuscripts 4Q12, 6Q1: Genesis. 4Q22: Exodus. 1Q3, 2Q5, 4Q11, 4Q45, 4Q46, 6Q2: Leviticus.[16] In some Qumran documents, YHWH is written in Paleo-Hebrew while the rest of the text is in Aramaic square script.[17] The vast majority of the Hasmonean coinage, as well as the coins of the First Jewish-Roman War and Bar Kokhba's revolt, bears Paleo-Hebrew legends. The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet fell completely out of use only after 135 CE.

Use by Samaritans

The paleo-Hebrew alphabet continued to be used by the Samaritans which has been adopted and is known as the Samaritan alphabet.[18] The Samaritans have continued to use the script for writing both Hebrew and Aramaic texts until the present day. A comparison of the earliest Samaritan inscriptions and the medieval and modern Samaritan manuscripts clearly indicates that the Samaritan script is a static script which was used mainly as a book hand.

According to the Babylonian Talmud

The Talmudic sages did not share a uniform stance on the subject of Paleo-Hebrew. Some stated that Paleo-Hebrew was the original script used by the Israelites at the time of the Exodus,[19] while others believed that Paleo-Hebrew merely served as a stopgap in a time when the original script (The Assyrian Script) was lost.[20] According to both opinions, Ezra the Scribe (c. 500 BCE) introduced, or reintroduced the Assyrian script to be used as the primary Alphabet for the Hebrew language.[19] The arguments given for both opinions are rooted in Jewish scripture and/or tradition.

A third opinion[21] in the Talmud states that the script never changed altogether. It would seem that the sage who expressed this opinion did not believe that Paleo-Hebrew ever existed, despite the strong arguments supporting it. His stance is rooted in a scriptural verse,[22] which makes reference to the shape of the letter vav. The sage argues further that, given the commandment to copy a Torah scroll directly from another, the script could not conceivably have been modified at any point. This third opinion was accepted by some early Jewish scholars,[23] and rejected by others, partially because it was permitted to write the Torah in Greek.[24]

Current use in Sacred Name Bibles

The Paleo-Hebrew script has been recently revived for specific use in several Sacred Name Bibles: including Zikarown Say’fer, The Besorah and the Halleluyah Scriptures. These translations use it for writing the Tetragrammaton and other divine names, incorporating these names written in this script in the midst of the English text.

Unicode

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was unified with the Phoenician alphabet and added to the Unicode Standard in July, 2006 with the release of version 5.0.

The Unicode block for Paleo-Hebrew, called Phoenician, is U+10900–U+1091F. It is intended for the representation of text in Palaeo-Hebrew, Archaic Phoenician, Phoenician, Early Aramaic, Late Phoenician cursive, Phoenician papyri, Siloam Hebrew, Hebrew seals, Ammonite, Moabite, and Punic.

| Phoenician[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1090x | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 |

| U+1091x | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤖 | 𐤗 | 𐤘 | 𐤙 | 𐤚 | 𐤛 | 𐤟 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Reinhard G. Kratz (11 November 2015). Historical and Biblical Israel: The History, Tradition, and Archives of Israel and Judah. OUP Oxford. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-104448-9.

[...] scribes wrote in Paleo-Hebrew, a local variant of the Phoenician alphabetic script [...]

- ↑ The Hebrew scripts, Volume 2, Salomo A. Birnbaum, Palaeographia, 1954, "To apply the term Phoenician to the script of the Hebrews is hardly suitable. I have therefore coined the term Palaeo-Hebrew."

- ↑ The site of Tel Zayit is about 50 km (35 miles) southwest of Jerusalem.

- ↑ An illustration of the Gezer script is available at this link.

- ↑ A transcription showing the script is available at this link.

- ↑ An illustration of the script used on Mesha's Stele is available at this link.

- ↑ The Newly Discovered Phoenician Inscription, New York Times, June 15, 1855, pg. 4.

- ↑ Angel Sáenz-Badillos (1993). A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- ↑ See Tetragrammaton#Dead Sea Scrolls Tetragrammaton: Dead Sea Scrolls.

- ↑ An illustration of the Siloam script is available at this link.

- ↑ An illustration of a tomb inscription said to be scratched onto an ossuary to identify the decedent is available here. An article describing the ossuaries Zvi Greenhut excavated from a burial cave in the south of Jerusalem can be found in Jerusalem Perspective (July 1, 1991), with links to other articles.

- ↑ Another tomb inscription is believed to be from the tomb of Shebna, an official of King Hezekiah. An illustration of the inscription may be viewed, but it is too large to be placed inline.

- ↑ An illustration of the Lachish script is available at this link.

- ↑ See Worker's appeal to governor.

- ↑ The conduct complained about is contrary to Exodus 22, which provides:“If you take your neighbor’s garment in pledge, you must return it to him before the sun sets; it is his only clothing, the sole covering for his skin. In what else shall he sleep?”

- ↑ Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

- ↑ e.g. File:Psalms Scroll.jpg

- ↑ An illustration of Samaritan script is available at this link.

- 1 2 Sanhedrin 21

- ↑ Megila 3, Shabbat 104

- ↑ Sanhedrin 22

- ↑ Exodus 27, 10

- ↑ Rabbeinu Chananel Sanhedrin 22

- ↑ Maimonides. "Mishne Torah Hilchos Stam 1:19".

References

- "Alphabet, Hebrew". Encyclopaedia Judaica (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth. Keter Publishing House. ISBN 965-07-0665-8

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia: The Hebrew Alphabet

- omniglot.com: Aramaic/Proto-Hebrew alphabet

- Ancient Hebrew alphabets

- The Alphabet of Biblical Hebrew

- 'Oldest Hebrew alphabet' is found

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||