Antlion

| Antlions Temporal range: 251–0 Ma Mesozoic – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult Distoleon tetragrammicus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Neuroptera |

| Suborder: | Myrmeleontiformia |

| Superfamily: | Myrmeleontoidea |

| Family: | Myrmeleontidae |

| Subfamilies | |

|

Acanthaclisinae | |

| Synonyms | |

Antlion, also spelled ant-lion and ant lion, is a name applied to a group of about 2,000 species of insects in the family Myrmeleontidae (sometimes misspelled as "Myrmeleonidae"). The best-known genus is Myrmeleon ("antlion"). Strictly speaking, the term "antlion" applies to the larval form of the members of this family, but while several languages have names for the adult, no word for them in English is widely used. Very rarely, the adults are called antlion lacewings.

The length of a fully grown, well-nourished predatory larva is typically up to 1.2 cm, and that of an adult up to 4 cm.[1]

The antlion larva is often called "doodlebug" in North America because of the odd winding, spiralling trails it leaves in the sand while looking for a good location to build its trap, as these trails look as if someone has doodled in the sand.[2]

Description and ecology

Antlions are worldwide in distribution, most commonly in arid and sandy habitats. A few species occur in cold-temperate places; a famous example is the European Euroleon nostras, whose scientific name means "our European lion". They can be fairly small to very large Neuroptera (wingspan range of 2–15 cm).[3]

The antlion larvae eat small arthropods – mainly ants – while the adults of some species eat pollen and nectar, while others are predators of small arthropods in the adult stage, too.[4] In certain species of Myrmeleontidae, such as Dendroleon pantheormis, the larva, although resembling that of Myrmeleon structurally, makes no pitfall, but seizes passing prey from the hole in which it shelters.[3]

The adult has two pairs of long, narrow, multiveined wings in which the apical veins enclose regular oblong spaces, and a long, slender abdomen. Although they greatly resemble dragonflies or damselflies, they belong to an entirely different infraclass among the winged insects. Antlions are easily distinguished from damselflies by their prominent, apically clubbed antennae which are about as long as head and thorax combined. Also, the pattern of wing venation differs, with the very long hypostigmatic cell (behind the fusion point of Sc and R1) being several times as long as wide. They also are very feeble fliers and are normally found fluttering about in the night, in search of a mate. The adult is thus rarely seen in the wild because it is typically active only in the evening.[3]

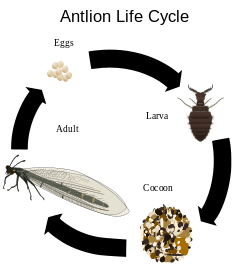

The lifecycle of the antlion begins with oviposition (egg-laying). The female antlion repeatedly taps the sand surface with the tip of her abdomen. She then inserts her abdomen into the sand and lays an egg. The antlion larva is a ferocious-appearing creature with a robust, fusiform body, a very plump abdomen, the thorax bearing three pairs of walking legs. The prothorax forms a slender mobile "neck" for the large, square, flattened head, which bears an enormous pair of sickle-like jaws with several sharp, hollow projections. The jaws are formed by the maxillae and mandibles, which in each pincer enclose a canal for injecting venom between them. Depending on species and where it lives, the larvae either hide under leaves or pieces of wood, in cracks of rocks, or dig pits in sandy areas. Antlion larvae are unusual among the insects as they lack an anus. All the metabolic waste generated during the larval stage is stored and is eventually emitted as meconium near the end of its pupal stage.[5]

The pupal stage of the antlion is quiescent. The larva makes a globular cocoon of sand stuck together with fine silk spun from a slender spinneret at the posterior end of the body. These cocoons may be buried several centimeters deep in the sand. It remains there for one month, until the completion of the transformation into the sexually mature insect, which then emerges from the case, leaving the pupal integument behind, and climbs to the surface. After about 20 minutes, the adult's wings are fully opened and it flies off in search of a mate. The adult is considerably larger than the larva; they exhibit the greatest disparity in size between larva and adult of any type of holometabolous insects, by virtue of the adults having an extremely thin, flimsy exoskeleton – in other words, they have extremely low mass per unit of volume.

Systematics

The closest living relatives of antlions are the owlflies (Ascalaphidae). The extinct Babinskaiidae, known only from fossils, were also very closely related. These three form the most strongly derived lineages of the superfamily Myrmeleontoidea.[6]

The numerous genera and species of antlions are for the largest part assigned to a diversity of subfamilies. A few genera, mostly fossil, are of more uncertain or basal position. The fossil record of antlions is very small by neuropteran standards. However, some Mesozoic fossils attest to the antlions' origin more than 150 million years ago. These were at one time separated as family Palaeoleontidae, but are now usually recognized as the most primitive examples of actual antlions.[4]

| Subfamilies, with some notable species and genera |

|---|

|

Antlions of uncertain systematic position are:[6]

- Palaeoleon (fossil)

- Porrerus

- Samsonileon (fossil)

Etymology

The exact meaning of the name "antlion" is uncertain. It has been thought to refer to ants forming a large percentage of the prey of the insect, the suffix "lion" merely suggesting destroyer or hunter. In any case, the term seems to go back to classical antiquity.[7]

The scientific name of the type genus Myrmeleo – and thus, the family as a whole – is derived from Ancient Greek léon (λέων) "lion" + mýrmex (μύρμηξ) "ant", in a literal translation of the names common across Europe.[7] In most European and Middle Eastern languages, at least the larvae are known under the local term corresponding to "antlion".[7]

Sand pit traps

An average-sized larva digs a pit about 2 in (5 cm) deep and 3 in (7.5 cm) wide at the edge. This behavior has also been observed in a family of flies, the Vermileonidae, whose larvae dig the same sort of pit to feed on ants. Having marked out the chosen site by a circular groove,[8][9] the antlion larva starts to crawl backwards, using its abdomen as a plough to shovel up the soil. By the aid of one front leg, it places consecutive heaps of loosened particles upon its head, then with a smart jerk throws each little pile clear of the scene of operations. Proceeding thus, it gradually works its way from the circumference towards the center. As it slowly moves round and round, the pit gradually gets deeper and deeper, until the slope angle reaches the critical angle of repose (that is, the steepest angle the sand can maintain, where it is on the verge of collapse from slight disturbance). When the pit is completed, the larva settles down at the bottom, buried in the soil with only the jaws projecting above the surface, often in a wide-opened position on either side of the very tip of the cone.

Since the sides of the pit consist of loose sand at its angle of repose,[10] they afford an insecure foothold to any small insects that inadvertently venture over the edge, such as ants. Slipping to the bottom, the prey is immediately seized by the lurking antlion; if it attempts to scramble up the treacherous walls of the pit, it is speedily checked in its efforts and brought down by showers of loose sand which are thrown at it from below by the larva. By throwing up loose sand from the bottom of the pit, the larva also undermines the sides of the pit, causing them to collapse and bring the prey with them. Thus, it does not matter whether the larva actually strikes the prey with the sand showers.

Antlion larvae are capable of capturing and killing a variety of insects and other arthropods, and can even subdue small spiders. The projections in the jaws of the larva are hollow and through this, the larva sucks the fluids out of its victim. After the contents are consumed, the dry carcass is flicked out of the pit. The larva readies the pit once again by throwing out collapsed material from the center, steepening the pit walls to the angle of repose.

Antlions are especially abundant in soft sand beneath trees or under overhanging rocks. The larvae prefer dry places that are protected from the rain. When it first hatches, the tiny larva specializes in very small insects, but as it grows larger, it constructs larger pits, and thus catches larger prey. Eventually, the larva attains its maximum size and undergoes metamorphosis. The entire length of time from egg-laying to adulthood may take two or three years due to the uncertainty and irregular nature of its food supply.

In Japan, Dendroleon jezoensis larvae can become coated with lichen, and were recorded at densities up to 344 per square metre. Many antlions take a long time (up to several years) to complete their lifecycle; they can survive for many months without feeding.[11]

-

Antlion larva trails (doodles) in sand

-

4.8cm)_DD11.176086%2C-4.335053%40Bobo-Dioulasso%2CBF_thu29oct2015-1054h.jpg)

Thorax and head (with club-shaped antenna) of antlion adult

-

Larva

-

20x closeup of larva

-

Video of antlion larva trying to catch prey with sand traps and eating a small spider

-

Video of a larva trapping an ant by throwing sand at it

Folklore

In popular folklore in the southern United States, people recite a poem or chant to make the antlion come out of its hole.[12] Similar practices have been recorded from Africa, the Caribbean, China and Australia.[13]

The Myrmecoleon was a mythical ant-lion hybrid written about in the Physiologus, where animal descriptions were paired with Christian morals. The ant-lion as described was said to starve to death because of its dual nature – the lion nature of the father could only eat meat, but the ant half from the mother could only eat grain chaff, thus the offspring could not eat either and would starve.[14] It was paired with the Biblical verse Matthew 5:37[15] The fictional ant-lion of Physiologus is probably derived from a misreading of Job 4:11.[14]

References

- ↑ Galveston County Master Gardeners: Beneficial insects in the garden

- ↑ "What are Antlions?". The Antlion Pit. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 Chisholm, 1911

- 1 2 Engel, Michael S. & Grimaldi, David A. (2007): The neuropterid fauna of Dominican and Mexican amber (Neuropterida, Megaloptera, Neuroptera). American Museum Novitates 3587: 1–58. PDF fulltext

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- 1 2 See references in Haaramo, Mikko (2008): Mikko's Phylogeny Archive: Neuroptera. Version of 2008-MAR-11. Retrieved 2008-APR-27.

- 1 2 3 Swanson, Mark (2007): The Antlion Pit – "Antlion" in the World's Languages. Retrieved 2008-MAY-04.

- ↑ Scharf, Inon & Ovadia, Ofer (2006): Factors influencing site abandonment and site selection in a sit-and-wait Predator: A review of pit-building antlion Larvae. Journal of Insect Behavior 19: 197-218. PDF fulltext

- ↑ Haaramo, Mikko (2008): Mikko's Phylogeny Archive: Neuroptera. Version of 2008-MAR-11. Retrieved 2008-APR-27.

- ↑ Botz, Jason T.; Loudon, Catherine; Barger, J. Bradley; Olafsen, Jeffrey S. & Steeples, Don W. (2003): Effects of slope and particle size on ant locomotion: Implications for choice of substrate by antlions. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 76(3): 426–435 abstract

- ↑ Insects as Predators by T New published by NSW University Press, 1991. Page 69.

- ↑ Howell, Jim (2006). Hey, Bug Doctor!: The Scoop on Insects in Georgia's Homes and Gardens. University of Georgia Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0820328049.

- ↑ Ouchley, Kelby (2011). Bayou-Diversity: Nature and People in the Louisiana Bayou Country. LSU Press. p. 85. ISBN 0807138614.

- 1 2 Dekkers, Midas (2000). Dearest Pet: On Bestiality. Verso. p. 78. ISBN 9781859843109.

- ↑ Grant, Robert M. (1999). Early Christians and Animals. Psychology Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 9780415202046.

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Myrmeleontidae. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ant-lion. |

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ant-lion". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ant-lion". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Look up antlion in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Glenurus gratus on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Antlion Death Trap, a National Geographic video posted on YouTube.

- Ant Lion Zoology, an informative and entertaining video about ant lions and their relatives

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||