Sufism in Pakistan

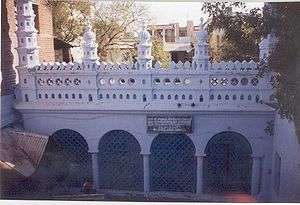

Sufism has an illustrious history in Pakistan and rest of South Asia evolving for over 1,000 years.[1] The presence of Sufism has been a leading entity increasing the reaches of Islam throughout South Asia.[2] Following the entrance of Islam in the early 8th century, Sufi mystic traditions became more visible during the 10th and 11th centuries of the Delhi Sultanate.[3] A conglomeration of four chronologically separate dynasties, the early Delhi Sultanate consisted of rulers from Turkic and Afghan lands.[4] This Persian influence flooded South Asia with Islam, Sufi thought, syncretic values, literature, education, and entertainment that has created an enduring impact on the presence of Islam in South Asia today.[5] Today, there are thousands of Sufi shrines and mausoleums which dot the landscape of Pakistan.

Sufism

Sufism is a branch of Islam, defined by adherents as the inner, mystical dimension of Islam; others contend that it is a perennial philosophy of existence that pre-dates religion, the expression of which flowered within Islam. Its essence has also been expressed via other religions and metareligious phenomena.[6][7][8] A practitioner of this tradition is generally known as a ṣūfī (صُوفِيّ). They belong to different ṭuruq or "orders" – congregations formed around a master – which meet for spiritual sessions (majalis), in meeting places known as zawiyahs, khanqahs, or tekke.[9] All Sufi orders (turuq) trace many of their original precepts from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his cousin and son-in-law Ali ibn Abi Talib, with the notable exception of the Sunni Naqshbandi order who claim to trace their origins through the first sunni Caliph, Abu Bakr.[10] However, Alevi, Bektashi[11] and Shia Muslims claim that every Sufi order traces its spiritual lineage (silsilah or Silsila) back to one of the Twelve Imams (even the Naqshbandi silsilah leads to the sixth imam Ja'far al-Sadiq and Salman the Persian, a renowned follower of the first imam Ali ibn Abi Talib), the spiritual heads of Islam who were foretold in the Hadith of the Twelve Successors and were all descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and Ali. Because of this Ali ibn Abi Talib is also called the father of Sufism.[12][13] Prominent orders include Alevi, Bektashi, Mevlevi, Ba 'Alawiyya, Chishti, Rifa'i, Khalwati, Naqshbandi, Nimatullahi, Oveyssi, Qadiria Boutshishia, Qadiriyyah, Qalandariyya, Sarwari Qadiri, Shadhiliyya and Suhrawardiyya.[14]

Early history

Sufism has been known in South Asia since its very beginnings. Some of the greatest and most renowned Sufis were from this region, including 8th-century saints such as Moinuddin Chishti and Ibrahim ibn Adham and their successors, e.g. Shaqiq al-Balkhi and al-Farabi (9th century).

Towards the end of the first millennium, a number of manuals began to be written summarizing the doctrines of Sufism and describing some typical Sufi practices. Two of the most famous of these are now available in English translation: the Kashf al-Mahjûb of Hujwiri, and the Risâla of Qushayri.[15]

Two of Imam Al Ghazali's greatest treatises, the "Revival of Religious Sciences" and the "Alchemy of Happiness," argued that Sufism originated from the Qur'an and was thus compatible with mainstream Islamic thought, and did not in any way contradict Islamic Law—being instead necessary to its complete fulfillment. This became the mainstream position among Islamic scholars for centuries, challenged only recently on the basis of selective use of a limited body of texts . Ongoing efforts by both traditionally trained Muslim scholars and Western academics are making Imam Al-Ghazali's works available in English translation for the first time,[16] allowing English-speaking readers to judge for themselves the compatibility of Islamic Law and Sufi doctrine.

Sufi orders appeared at the beginning of 12th century and have established strong links with the state apparatus since then. This connection became apparent when Sufis were actively encouraged by Sunni dynasties to convert Ismaili Shia presence in Sindh.[17]

Sufi Tariqahs

Shadhiliyya

Shadhilyya was founded by Imam Nooruddeen Abu Al Hasan Ali Ash Sadhili Razi. Fassiya branch of Shadhiliyya was brought to South Asia by Sheikh Aboobakkar Miskeen sahib Radiyallah of Kayalpatnam and Sheikh Mir Ahmad Ibrahim Raziyallah of Madurai. Mir Ahmad Ibrahim is the first of the three Sufi saints revered at the Madurai Maqbara in Tamil Nadu. There are more than 70 branches of Shadhiliyya and in South Asia. Of these, the Fassiyatush Shadhiliyya is the most widely practised order.[18]

Chishtiyyah

The Chishtiyya order emerged from Central Asia and Persia. The first saint was Abu Ishaq Shami (d. 940–41) establishing the Chishti order in Chisht-i-Sharif within Afghanistan[19] Furthermore, Chishtiyya took root with the notable saint Moinuddin Chishti (d. 1236) who championed the order within Delhi Sultanate, making it one of the largest orders in South Asia today.[20] Scholars also mentioned that he had been a part-time disciple of Abu Najib Suhrawardi.[21] Khwaja Moiuddin Chishti was originally from Sistan (eastern Iran, southwest Afghanistan) and grew up as a well traveled scholar to Central Asia, Middle East, and South Asia.[22] He reached Delhi in 1193 during the end of Ghurid reign, then shortly settled in Ajmer-Rajasthan when the Delhi Sultanate formed. Moinuddin Chishti's Sufi and social welfare activities dubbed Ajmer the "nucleus for the Islamization of central and southern South Asia."[21] The Chishti order formed khanqah to reach the local communities, thus helping Islam spread with charity work. Islam in South Asia grew with the efforts of dervishes, not with violent bloodshed or forced conversion. Chishtis were famous establishing khanqahs and for their simple teachings of humanity, peace, and generosity. This group drew an unprecedented amount of Hindus of lower and higher castes within vicinity.[21] Until this day, both Muslims and non-Muslims visit the famous tomb of Moinuddin Chishti; it has become even a popular tourist and pilgrimage destination. Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (d. 1605), the 3rd Mughal ruler frequented Ajmer as a pilgrim, setting a tradition for his constituents.[23] Successors of Khwaja Moinudden Chishti include eight additional saints; together, these names are considered the big eight of the medieval Chishtiyya order. Moinuddin Chishti (d. 1233 in Ajmer, India) Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki (d. 1236 in Delhi, India) Fariduddin Ganjshakar (d. 1265 in Pakpattan, Pakistan) Nizamuddin Auliya (d. 1335 in Delhi). Nasiruddin Chiragh Dehlavi[24] Bande Nawaz (d. 1422 in Gulbarga, India)[25] Akhi Siraj Aainae Hind (d. 1357 in Bengal, India[26] Alaul Haq Pandavi[27] Ashraf Jahangir Semnani(d. 1386, Kichaucha India)[28]

The Ishq-Nuri Tariqa is a contemporary expression and evolution of the traditional Chishti spiritual path, which was founded in Lahore, Pakistan, in the 1960s.

Suhrwardiyyah

The founder of this order was Abdul-Wahir Abu Najib as-Suhrawardi (d. 1168).[29] He was actually a disciple of Ahmad Ghazali, who is also the younger brother of Abu Hamid Ghazali. The teachings of Ahmad Ghazali led to the formation of this order. This order was prominent in medieval Iran prior to Persian migrations into South Asia during the Mongol Invasion[30] Consequently, it was Abu Najib as-Suhrawardi’s nephew that helped bring the Suhrawardiyyah to mainstream awareness.[31] Abu Hafs Umar as-Suhrawardi (d. 1243) wrote numerous treatises on Sufi theories. Most notably, the text trans. “Gift of Deep Knowledge: Awa’rif al-Mar’if” was so widely read that it became a standard book of teaching in South Asiaan madrasas.[29] This helped spread the Sufi teachings of the Suhrawardiyya. Abu Hafs was a global ambassador of his time. From teaching in Baghdad to diplomacy between the Ayyubid rulers in Egypt and Syria, Abu Hafs was a politically involved Sufi leader. By keeping cordial relations with the Islamic empire, Abu Hafs’s followers in South Asia continued to approve of his leadership and approve political participation of Sufi orders.[29]

Kubrawiyyah

This order was founded by Abu'l Jannab Ahmad, nicknamed Najmuddin Kubra (d. 1221) who was from the border between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan[32] This Sufi saint was a widely acclaimed teacher with travels to Turkey, Iran, and Kashmir. His education also fostering generations of students who became saints themselves.[30] This order became important in Kashmir during the late 14th century.[33] Kubra and his students made significant contributions to Sufi literature with mystical treatises, mystical psychology, and instructional literature such as text "al-Usul al-Ashara" and "Mirsad ul Ibad."[30] These popular texts regarding are still mystic favorites in South Asia and in frequent study. The Kubrawiya remains in Kashmir - India and within Huayy populations in China.[30] Noorbakshia Sufi order is present in the Baltistan region of Gilgit-Baltistan.

Naqshbandiyyah

The origin of this order can be traced back to Khwaja Ya‘qub Yusuf al-Hamadani (d. 1390), who lived in Central Asia.[30][34] It was later organized by Baha’uddin Naqshband (b. 1318–1389) of Tajik and Turkic background.[30] He is widely referred to as the founder of the Naqshbandi order. Khwaja Muhammad al-Baqi Billah Berang (d. 1603) introduced the Naqshbandiyyah to South Asia.[20][30] This order was particularly popular Mughal elites due to ancestral links to the founder, Khawja al-Hamadani[35] [36] Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty in 1526, was already initiated in the Naqshbandi order prior to conquering South Asia. This royal affiliation gave considerable impetus to the order.[4]

Qadiriyyah

The Qadiriyyah order was founded by Abdul-Qadir Gilani who was originally from Iran (d. 1166)[30] It is popular among the Muslims of South Asia.[37] The Qadiriyyah has two off shoots Zahidi Qadri and Sarwar Qadri. The Sarwari Qadri Order was founded by Hazrat Sakhi Sultan Bahu (RA).

Sarwari Qadri

The Sarwari Qadri order was founded by Sultan Bahu which branched out of the Qadiriyyah order. Hence, it follows the same approach of the order but unlike most Sufi orders, it does not follow a specific dress code, seclusion, or other lengthy exercises. Its mainstream philosophy is related directly to the heart and contemplating on the name of Allah[38] i.e. the word الله (allāh) as written on own heart.[39]

Mujahhidiyyah

Less accurate information is known about the following other orders within South Asia: Mujahhidiyyah.

Opposing schools of thought

Decline of Sufism in Pakistan

Sufism started to lose its role as a powerful influence in the life of the Muslims of Pakistan since the early 1970s. The elections in 1970 gave rise to orthodox Muslim parties that emphasized Sharia and were hostile to heterodox folk Sufi traditions. The mass media and economic migration of Pakistanis to the Middle East exposed to them to the Muslims of other nations. The Umrah and Hajj travel to Makkah and Madina became easier and cost effective due to direct air travel. Millions of Pakistanis performed Haj and the society became more religious. The Muslim television channels also increased the awareness of Sharia and Sufi traditions declined. The Pakistan's Muslim society questioned and opposed the folk and heterodox Sufi traditions. Pakistan witnessed the growth of the Wahhabi movement with many Madrasa and mosques moving to Salafi Islam. The Urs, the death anniversary of a Sufi saint, had turned into yearly fairs over the centuries where entertainment, music, trade and commerce took precedence over religion. The orthodox Muslims violently opposed these practices, termed it as shirk and many incidents violent confrontations took place.[40] Sufism does not play a prominent role in Pakistani society any more. Many hardline Muslims and political movements are not in favor of it in Pakistan. Many folk traditions of Sufism are now considered to be haram or forbidden in Islam.[41] The Urs of Sufi saint in Karachi, Abdullah Shah Ghazi and Pir Mangho has seen steady decline of attendance over the years.

Attacks on Sufi shrines

Sufism, a mystical Islamic tradition, has a long history and a large popular following in Pakistan. Popular Sufi culture is centred on Thursday night gatherings at shrines and annual festivals which feature Sufi music and dance. The Sufi teachings of Islam have intermingled with local folk tribal and pagan practices in Pakistan and rest of South Asia to produce distinct traditions that are not considered to be Muslim beliefs. Most Islamic fundamentalists criticise its popular character, which in their view, does not accurately reflect the teachings and practice of the Prophet and his companions.[42][43]

Since March 2005, 209 people have been killed and 560 injured in 29 different terrorist attacks targeting shrines devoted to Sufi saints in Pakistan, according to data compiled by the Center for Islamic Research Collaboration and Learning (CIRCLe).[44] As of 2010, the attacks have increased each year. The attacks are generally attributed to banned militant organisations.[45]

See also

- List of mausolea and shrines in Pakistan

- Mausoleums of Multan

- Chishtiyyah

- Suhrawardiyya

- Shadhiliyya

- Kubrawiyyah

- Naqshbandiyyah

- Qadiriyyah

- List of Sufi saints

- Islam in Pakistan

References

- ↑ Jafri, Saiyid Zaheer Husain (2006). The Islamic Path: Sufism, Politics, and society in India. New Delhi: Konrad Adenauer Foundation.

- ↑ Schimmel, p.346

- ↑ Schimmel, Anniemarie (1975). "Sufism in Indo-Pakistan". Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 345.

- 1 2 Walsh, Judith E. (2006). A Brief History of India. Old Westbury: State University of New York. p. 58.

- ↑ Jafri, Saiyid Zaheer Husain (2006). The Islamic Path: Sufism, Politics, and Society in India. New Delhi: Konrad Adenauer Foundation. p. 4.

- ↑ Alan Godlas, University of Georgia, Sufism's Many Paths, 2000, University of Georgia

- ↑ Nuh Ha Mim Keller, "How would you respond to the claim that Sufism is Bid'a?", 1995. Fatwa accessible at: Masud.co.uk

- ↑ Zubair Fattani. "The meaning of Tasawwuf". Islamic Academy.

- ↑ The New Encyclopedia Of Islam By Cyril Glassé, p.499

- ↑ Kabbani, Muhammad Hisham (2004). Classical Islam and the Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition. Islamic Supreme Council of America. p. 557. ISBN 1-930409-23-0.

- ↑ http://bektashiorder.com/excerpts-from-babas-book

- ↑ http://www.spiritualfoundation.net/fatherofsufism.htm

- ↑ http://khawajamoinuddin.wordpress.com/hazrat-ali-the-father-of-sufism/

- ↑ The Jamaat Tableegh and the Deobandis by Sajid Abdul Kayum, Chapter 1: Overview and Background.

- ↑ The most recent version of the Risâla is the translation of Alexander Knysh, Al-Qushayri's Epistle on Sufism: Al-risala Al-qushayriyya Fi 'ilm Al-tasawwuf (ISBN 978-1859641866). Earlier translations include a partial version by Rabia Terri Harris (Sufi Book of Spiritual Ascent) and complete versions by Harris, and Barbara R. Von Schlegell.

- ↑ Several sections of the Revival of Religious Sciences have been published in translation by the Islamic Texts Society; see http://www.fonsvitae.com/sufism.html. The Alchemy of Happiness has been published in a complete translation by Claud Field (ISBN 978-0935782288), and presents the argument of the much larger Revival of Religious Sciences in summary form.

- ↑ Pinto, Paulo (2003). "Dangerous Liaisons: Sufism and the State in Syria" (PDF). IWM Junior Visiting Fellows' Conferences XIV (1). Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ↑ "Fassiyathush Shazuliya | tariqathush Shazuliya | Tariqa Shazuliya | Sufi Path | Sufism | Zikrs | Avradhs | Daily Wirdh | Thareeqush shukr |Kaleefa's of the tariqa | Sheikh Fassy | Ya Fassy | Sijl | Humaisara | Muridheens | Prostitute Entering Paradise". Shazuli.com. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ↑ Durán, Khalid; Reuven Firestone; Abdelwahab Hechiche. Children of Abraham: An Introduction to Islam for Jews. Harriet and Robert Heilbrunn Institute for International Interreligious Understanding, American Jewish Committee. p. 204.

- 1 2 Alvi 13

- 1 2 3 Schimmel 346

- ↑ Aquil 6

- ↑ Walsh 80

- ↑ Aquil 8

- ↑ Askari, Syed Hasan, Tazkira-i Murshidi—Rare Malfuz of the 15th-Century Sufi Saint of Gulbarga. Proceedings of the Indian Historical Records Commission (1952)

- ↑ 'Akhbarul Akhyar' By Abdal Haqq Muhaddith Dehlwi (d.1052H-1642 CE). A short biography of the prominent sufis of India have been mentioned in this book including that of Hazrat Akhi Siraj Aainae Hind)

- ↑ 'Akhbarul Akhyar' By Abdal Haqq Muhaddith Dehlwi (d.1052H-1642 CE). A short biography of the prominent sufis of India have been mentioned in this book including that of Hazrat Alaul Haq Pandavi

- ↑ Ashraf, Syed Waheed, Hayate Syed Ashraf Jahangir Semnani, Published 1975, India

- 1 2 3 Schimmel 245

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Schimmel 256, Zargar

- ↑ Zargar, Schimmel

- ↑ Schimmel 254

- ↑ Schimmel 255

- ↑ Lal, Mohan. Encyclopædia of Indian literature 5. p. 4203.

- ↑ Ohtsuka, Kazuo. "Sufism". OxfordIslamicStudies.com. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- ↑ Alvi 15

- ↑ Gladney, Dru. "Muslim Tombs and Ethnic Folklore: Charters for Hui Identity" Journal of Asian Studies, August 1987, Vol. 46 (3): 495-532; pp. 48-49 in the PDF file.

- ↑

- ↑ Sult̤ān Bāhū (1998). Death Before Dying: The Sufi Poems of Sultan Bahu. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-92046-0.

- ↑ Sufism threatened

- ↑ Mystical Islam 'under threat' in Pakistan

- ↑ Produced by Charlotte Buchen. "Sufism Under Attack in Pakistan" (video). The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ↑ Huma Imtiaz; Charlotte Buchen (6 January 2011). "The Islam That Hard-Liners Hate" (blog). The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ↑ a think-tank based in Rawalpindi

- ↑ Sunni Ittehad Council: Sunni Barelvi activism against Deobandi-Wahhabi terrorism in Pakistan – by Aarish U. Khan| criticalppp.com| Let Us Build Pakistan

Bibliography

- De Bruijn, The Qalandariyyat in Persian Mystical Poetry from Sana'i, in The Heritage of Sufism, 2003.

- Ashk Dahlén, The Holy Fool in Medieval Islam: The Qalandariyat of Fakhr al-din Araqi, Orientalia Suecana, vol.52, 2004.

External links

- The Islam That Hard-Liners Hate

- Pakistan's Sufis Preach Faith and Ecstasy

- Sufism in Pakistan – the tolerant antidote?

- Mystical Islam 'under threat' in Pakistan

- Steeped in ancient mysticism, the passion of Pakistani Sufis infuriates Taliban

- The Sufis of India and Pakistan

- Sufism and Pakistani society

- Why are they targeting the Sufis?