Bit error rate

In digital transmission, the number of bit errors is the number of received bits of a data stream over a communication channel that have been altered due to noise, interference, distortion or bit synchronization errors.

The bit error rate (BER) is the number of bit errors per unit time. The bit error ratio (also BER) is the number of bit errors divided by the total number of transferred bits during a studied time interval. BER is a unitless performance measure, often expressed as a percentage.[1]

The bit error probability pe is the expectation value of the bit error ratio. The bit error ratio can be considered as an approximate estimate of the bit error probability. This estimate is accurate for a long time interval and a high number of bit errors.

Example

As an example, assume this transmitted bit sequence:

0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1

and the following received bit sequence:

0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1,

The number of bit errors (the underlined bits) is, in this case, 3. The BER is 3 incorrect bits divided by 10 transferred bits, resulting in a BER of 0.3 or 30%.

Packet error ratio

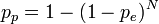

The packet error ratio (PER) is the number of incorrectly received data packets divided by the total number of received packets. A packet is declared incorrect if at least one bit is erroneous. The expectation value of the PER is denoted packet error probability pp, which for a data packet length of N bits can be expressed as

,

,

assuming that the bit errors are independent of each other. For small bit error probabilities, this is approximately

Similar measurements can be carried out for the transmission of frames, blocks, or symbols.

Factors affecting the BER

In a communication system, the receiver side BER may be affected by transmission channel noise, interference, distortion, bit synchronization problems, attenuation, wireless multipath fading, etc.

The BER may be improved by choosing a strong signal strength (unless this causes cross-talk and more bit errors), by choosing a slow and robust modulation scheme or line coding scheme, and by applying channel coding schemes such as redundant forward error correction codes.

The transmission BER is the number of detected bits that are incorrect before error correction, divided by the total number of transferred bits (including redundant error codes). The information BER, approximately equal to the decoding error probability, is the number of decoded bits that remain incorrect after the error correction, divided by the total number of decoded bits (the useful information). Normally the transmission BER is larger than the information BER. The information BER is affected by the strength of the forward error correction code.

Analysis of the BER

The BER may be evaluated using stochastic (Monte Carlo) computer simulations. If a simple transmission channel model and data source model is assumed, the BER may also be calculated analytically. An example of such a data source model is the Bernoulli source.

Examples of simple channel models used in information theory are:

- Binary symmetric channel (used in analysis of decoding error probability in case of non-bursty bit errors on the transmission channel)

- Additive white gaussian noise (AWGN) channel without fading.

A worst-case scenario is a completely random channel, where noise totally dominates over the useful signal. This results in a transmission BER of 50% (provided that a Bernoulli binary data source and a binary symmetrical channel are assumed, see below).

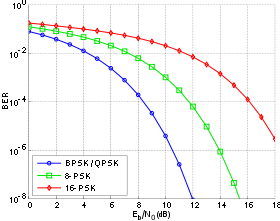

In a noisy channel, the BER is often expressed as a function of the normalized carrier-to-noise ratio measure denoted Eb/N0, (energy per bit to noise power spectral density ratio), or Es/N0 (energy per modulation symbol to noise spectral density).

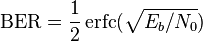

For example, in the case of QPSK modulation and AWGN channel, the BER as function of the Eb/N0 is given by:

.[2]

.[2]

People usually plot the BER curves to describe the performance of a digital communication system. In optical communication, BER(dB) vs. Received Power(dBm) is usually used; while in wireless communication, BER(dB) vs. SNR(dB) is used.

Measuring the bit error ratio helps people choose the appropriate forward error correction codes. Since most such codes correct only bit-flips, but not bit-insertions or bit-deletions, the Hamming distance metric is the appropriate way to measure the number of bit errors. Many FEC coders also continuously measure the current BER.

A more general way of measuring the number of bit errors is the Levenshtein distance. The Levenshtein distance measurement is more appropriate for measuring raw channel performance before frame synchronization, and when using error correction codes designed to correct bit-insertions and bit-deletions, such as Marker Codes and Watermark Codes.[3]

Mathematical draft

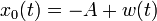

The BER is the likelihood of a bit misinterpretation due to electrical noise  . Considering a bipolar NRZ transmission, we have

. Considering a bipolar NRZ transmission, we have

for a "1" and

for a "1" and  for a "0". Each of

for a "0". Each of  and

and  has a period of

has a period of  .

.

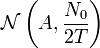

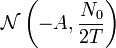

Knowing that the noise has a bilateral spectral density  ,

,

is

is

and  is

is  .

.

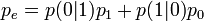

Returning to BER, we have the likelihood of a bit misinterpretation  .

.

and

and

where  is the threshold of decision, set to 0 when

is the threshold of decision, set to 0 when  .

.

We can use the average energy of the signal  to find the final expression :

to find the final expression :

±§

±§

Bit error rate test

BERT or bit error rate test is a testing method for digital communication circuits that uses predetermined stress patterns consisting of a sequence of logical ones and zeros generated by a test pattern generator.

A BERT typically consists of a test pattern generator and a receiver that can be set to the same pattern. They can be used in pairs, with one at either end of a transmission link, or singularly at one end with a loopback at the remote end. BERTs are typically stand-alone specialised instruments, but can be personal computer–based. In use, the number of errors, if any, are counted and presented as a ratio such as 1 in 1,000,000, or 1 in 1e06.

Common types of BERT stress patterns

- PRBS (pseudorandom binary sequence) – A pseudorandom binary sequencer of N Bits. These pattern sequences are used to measure jitter and eye mask of TX-Data in electrical and optical data links.

- QRSS (quasi random signal source) – A pseudorandom binary sequencer which generates every combination of a 20-bit word, repeats every 1,048,575 words, and suppresses consecutive zeros to no more than 14. It contains high-density sequences, low-density sequences, and sequences that change from low to high and vice versa. This pattern is also the standard pattern used to measure jitter.

- 3 in 24 – Pattern contains the longest string of consecutive zeros (15) with the lowest ones density (12.5%). This pattern simultaneously stresses minimum ones density and the maximum number of consecutive zeros. The D4 frame format of 3 in 24 may cause a D4 yellow alarm for frame circuits depending on the alignment of one bits to a frame.

- 1:7 – Also referred to as 1 in 8. It has only a single one in an eight-bit repeating sequence. This pattern stresses the minimum ones density of 12.5% and should be used when testing facilities set for B8ZS coding as the 3 in 24 pattern increases to 29.5% when converted to B8ZS.

- Min/max – Pattern rapid sequence changes from low density to high density. Most useful when stressing the repeater’s ALBO feature.

- All ones (or mark) – A pattern composed of ones only. This pattern causes the repeater to consume the maximum amount of power. If DC to the repeater is regulated properly, the repeater will have no trouble transmitting the long ones sequence. This pattern should be used when measuring span power regulation. An unframed all ones pattern is used to indicate an AIS (also known as a blue alarm).

- All zeros – A pattern composed of zeros only. It is effective in finding equipment misoptioned for AMI, such as fiber/radio multiplex low-speed inputs.

- Alternating 0s and 1s - A pattern composed of alternating ones and zeroes.

- 2 in 8 – Pattern contains a maximum of four consecutive zeros. It will not invoke a B8ZS sequence because eight consecutive zeros are required to cause a B8ZS substitution. The pattern is effective in finding equipment misoptioned for B8ZS.

- Bridgetap - Bridge taps within a span can be detected by employing a number of test patterns with a variety of ones and zeros densities. This test generates 21 test patterns and runs for 15 minutes. If a signal error occurs, the span may have one or more bridge taps. This pattern is only effective for T1 spans that transmit the signal raw. Modulation used in HDSL spans negates the bridgetap patterns' ability to uncover bridge taps.

- Multipat - This test generates five commonly used test patterns to allow DS1 span testing without having to select each test pattern individually. Patterns are: all ones, 1:7, 2 in 8, 3 in 24, and QRSS.

- T1-DALY and 55 OCTET - Each of these patterns contain fifty-five (55), eight bit octets of data in a sequence that changes rapidly between low and high density. These patterns are used primarily to stress the ALBO and equalizer circuitry but they will also stress timing recovery. 55 OCTET has fifteen (15) consecutive zeroes and can only be used unframed without violating one's density requirements. For framed signals, the T1-DALY pattern should be used. Both patterns will force a B8ZS code in circuits optioned for B8ZS.

Bit error rate tester

A bit error rate tester (BERT), also known as a bit error ratio tester or bit error rate test solution (BERTs) is electronic test equipment used to test the quality of signal transmission of single components or complete systems.

The main building blocks of a BERT are:

- Pattern generator, which transmits a defined test pattern to the DUT or test system

- Error detector connected to the DUT or test system, to count the errors generated by the DUT or test system

- Clock signal generator to synchronize the pattern generator and the error detector

- Digital communication analyser is optional to display the transmitted or received signal

- Electrical-optical converter and optical-electrical converter for testing optical communication signals

See also

References

- ↑ Jit Lim (14 December 2010). "Is BER the bit error ratio or the bit error rate?". EDN. Retrieved 2015-02-16.

- ↑ Digital Communications, John Proakis, Massoud Salehi, McGraw-Hill Education, Nov 6, 2007

- ↑ "Keyboards and Covert Channels" by Gaurav Shah, Andres Molina, and Matt Blaze (2006?)

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C" (in support of MIL-STD-188).

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C" (in support of MIL-STD-188).