Stochastic context-free grammar

Grammar theory to model symbol strings originated from work in computational linguistics aiming to understand the structure of natural languages.[1][2][3] Probabilistic context free grammars (PCFGs) have been applied in probabilistic modeling of RNA structures almost 40 years after they were introduced in computational linguistics.[4][5][6][7][8]

PCFGs extend context-free grammars similar to how hidden Markov models extend regular grammars. Each production is assigned a probability. The probability of a derivation (parse) is the product of the probabilities of the productions used in that derivation. These probabilities are typically computed by machine learning on large databases. A probabilistic grammar's validity is constrained by context of its training dataset.

PCFGs have application in areas as diverse as natural language processing to the study the structure of RNA molecules and design of programming languages. Designing efficient PCFGs has to weigh factors of scalability and generality. Issues such as grammar ambiguity must be resolved. The grammar design affects results accuracy. Grammar parsing algorithms have various time and memory requirements.

Definitions

Derivation: The process of recursive generation of strings from a grammar.

Parsing: Finding a valid derivation using an automaton.

Parse Tree: The alignment of the grammar to a sequence.

An example of a parser for PCFG grammars is the pushdown automaton. The algorithm parses grammar nonterminals from left to right in a stack-like manner. This brute-force approach is not very efficient. In RNA secondary structure prediction variants of the Cocke–Younger–Kasami (CYK) algorithm (CYK) algorithm provide more efficient alternatives to grammar parsing than pushdown automata.[9] Another example of a PCFG parser is the Stanford Statistical Parser which has been trained using Treebank,.[10]

Formal definition

Similar to a CFG, a probabilistic context-free grammar G can be defined by a quintuple:

where

- M is the set of non-terminal symbols

- T is the set of terminal symbols

- R is the set of production rules

- S is the start symbol

- P is the set of probabilities on production rules

Relation with Hidden Markov Models

PCFGs models extend context-free grammars the same way as hidden Markov models extend regular grammars.

The Inside-Outside algorithm is an analogue of the Forward-Backward algorithm. It computes the total probability of all derivations that are consistent with a given sequence, based on some PCFG. This is equivalent to the probability of the PCFG generating the sequence, and is intuitively a measure of how consistent the sequence is with the given grammar. The Inside-Outside algorithm is used in model parametrization to estimate prior frequencies observed from training sequences in the case of RNAs.

Dynamic programming variants of the CYK algorithm find the Viterbi parse of a RNA sequence for a PCFG model. This parse is the most likely derivation of the sequence by the given PCFG.

Grammar construction

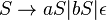

Context-free grammars are represented as a set of rules inspired from attempts to model natural languages.[3] The rules are absolute and have a typical syntax representation known as Backus-Naur Form. The production rules consist of terminal  and non-terminal S symbols and a blank

and non-terminal S symbols and a blank  may also be used as an end point. In the production rules of CFG and PCFG the left side has only one nonterminal whereas the right side can be any string of terminal or nonterminals. In PCFG nulls are excluded.[9] An example of a grammar:

may also be used as an end point. In the production rules of CFG and PCFG the left side has only one nonterminal whereas the right side can be any string of terminal or nonterminals. In PCFG nulls are excluded.[9] An example of a grammar:

This grammar can be shortened using the | 'or' character into:

Terminals in a grammar are words and through the grammar rules a non-terminal symbol is transformed into a string of either terminals and/or non-terminals. The above grammar is read as "beginning from a terminal S the emission can generate either a or b or  ".

Its derivation is:

".

Its derivation is:

Ambiguous grammar may result in ambiguous parsing if applied on homographs since the same word sequence can have more than one interpretation. Pun sentences such as the newspaper headline "Iraqi Head Seeks Arms" are an example of ambiguous parses.

One strategy of dealing with ambiguous parses (originating with grammarians as early as Pāṇini) is to add yet more rules, or prioritize them so that one rule takes precedence over others. This, however, has the drawback of proliferating the rules, often to the point where they become difficult to manage. Another difficulty is overgeneration, where unlicensed structures are also generated.

Probabilistic grammars circumvent these problems by ranking various productions on frequency weights, resulting in a "most likely" (winner-take-all) interpretation. As usage patterns are altered in diachronic shifts, these probabilistic rules can be re-learned, thus upgrading the grammar.

Assigning probability to production rules makes a PCFG. These probabilities are informed by observing distributions on a training set of similar composition to the language to be modeled. On most samples of broad language, probabilistic grammars where probabilities are estimated from data typically outperform hand-crafted grammars. CFGs when contrasted with PCFGs are not applicable to RNA structure prediction because while they incorporate sequence-structure relationship they lack the scoring metrics that reveal a sequence structural potential [11]

Applications

RNA structure prediction

Energy minimization[12][13] and PCFG provide ways to predicting RNA secondary structure with comparable performance.[4][5][9] However structure prediction by PCFGs is scored probabilistically rather than by minimum free energy calculation. PCFG model parameters are directly derived from frequencies of different features observed in databases of RNA structures [11] rather than by experimental determination as is the case with energy minimization methods.[14][15]

The types of various structure that can be modeled by an PCFG include long range interactions, pairwise structure and other nested structures. However, pseudoknots can not be modeled.[4][5][9] PCFGs extend CFG by assigning probabilities to each production rule. A maximum probability parse tree from the grammar implies a maximum probability structure. Since RNAs preserve their structures over their primary sequence; RNA structure prediction can be guided by combining evolutionary information from comparative sequence analysis with biophysical knowledge about a structure plausibility based on such probabilities. Also search results for structural homologs using PCFG rules are scored according to PCFG derivations probabilities. Therefore building grammar to model the behavior of base-pairs and single-stranded regions starts with exploring features of structural multiple sequence alignment of related RNAs.[9]

The above grammar generates a string in an outside-in fashion, that is the basepair on the furthest extremes of the terminal is derived first. So a string such as  is derived by first generating the distal a's on both sides before moving inwards:

is derived by first generating the distal a's on both sides before moving inwards:

A PCFG model extendibility allows constraining structure prediction by incorporating expectations about different features of an RNA . Such expectation may reflect for example the propensity for assuming a certain structure by an RNA.[11] However incorporation of too much information may increase PCFG space and memory complexity and it is desirable that a PCFG-based model be as simple as possible.[11][16]

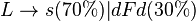

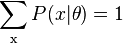

Every possible string x a grammar generates is assigned a probability weight  given the PCFG model

given the PCFG model  . It follows that the sum of all probabilities to all possible grammar productions is

. It follows that the sum of all probabilities to all possible grammar productions is  . The scores for each paired and unpaired residue explain likelihood for secondary structure formations. Production rules also allow scoring loop lengths as well as the order of base pair stacking hence it is possible to explore the range of all possible generations including suboptimal structures from the grammar and accept or reject structures based on score thresholds.[9][11]

. The scores for each paired and unpaired residue explain likelihood for secondary structure formations. Production rules also allow scoring loop lengths as well as the order of base pair stacking hence it is possible to explore the range of all possible generations including suboptimal structures from the grammar and accept or reject structures based on score thresholds.[9][11]

Implementations

RNA secondary structure implementations based on PCFG approaches can be utilized in :

- Finding consensus structure by optimizing structure joint probabilities over MSA.[16][17]

- Modeling base-pair covariation to detecting homology in database searches.[4]

- pairwise simultaneous folding and alignment.[18][19]

Different implementation of these approaches exist. For example Pfold is used in secondary structure prediction from a group of related RNA sequences,[16] covariance models are used in searching databases for homologous sequences and RNA annotation and classification,[4][20] RNApromo, CMFinder and TEISER are used in finding stable structural motifs in RNAs.[21][22][23]

Design considerations

PCFG design impacts the secondary structure prediction accuracy. Any useful structure prediction probabilistic model based on PCFG has to maintain simplicity without much compromise to prediction accuracy. Too complex a model of excellent performance on a single sequence may not scale.[9] A grammar based model should be able to:

- Find the optimal alignment between a sequence and the PCFG.

- Score the probability of the structures for the sequence and subsequences.

- Parameterize the model by training on sequences/structures.

- Find the optimal grammar parse tree (CYK algorithm).

- Check for ambiguous grammar (Conditional Inside algorithm).

The resulting of multiple parse trees per grammar denotes grammar ambiguity. This may be useful in revealing all possible base-pair structures for a grammar. However an optimal structure is the one where there is one and only one correspondence between the parse tree and the secondary structure.

Two types of ambiguities can be distinguished. Parse tree ambiguity and structural ambiguity. Structural ambiguity does not affect thermodynamic approaches as the optimal structure selection is always on the basis of lowest free energy scores.[11] Parse tree ambiguity concerns the existence of multiple parse trees per sequence. Such an ambiguity can reveal all possible base-paired structures for the sequence by generating all possible parse trees then finding the optimal one.[24][25][26] In the case of structural ambiguity multiple parse trees describe the same secondary structure. This obscures the CYK algorithm decision on finding an optimal structure as the correspondence between the parse tree and the structure is not unique.[27] Grammar ambiguity can be checked for by the conditional-inside algorithm.[9][11]

Building a PCFG model

A probabilistic context free grammar consists of terminal and nonterminal variables. Each feature to be modeled has a production rule that is assigned a probability estimated from a training set of RNA structures. Production rules are recursively applied until only terminal residues are left.

A starting non-terminal  produces loops. The rest of the grammar proceeds with parameter

produces loops. The rest of the grammar proceeds with parameter  that decide whether a loop is a start of a stem or a single stranded region s and parameter

that decide whether a loop is a start of a stem or a single stranded region s and parameter  that produces paired bases.

that produces paired bases.

The formalism of this simple PCFG looks like:

The application of PCFGs in predicting structures is a multi-step process. In addition, the PCFG itself can be incorporated into probabilistic models that consider RNA evolutionary history or search homologous sequences in databases. In an evolutionary history context inclusion of prior distributions of RNA structures of a structural alignment in the production rules of the PCFG facilitates good prediction accuracy.[17]

A summary of general steps for utilizing PCFGs in various scenarios:

- Generate production rules for the sequences.

- Check ambiguity.

- Recursively generate parse trees of the possible structures using the grammar.

- Rank and score the parse trees for the most plausible sequence.[9]

Algorithms

Several algorithms dealing with aspects of PCFG based probabilistic models in RNA structure prediction exist. For instance the inside-outside algorithm and the CYK algorithm. The inside-outside algorithm is a recursive dynamic programming scoring algorithm that can follow expectation-maximization paradigms. It computes the total probability of all derivations that are consistent with a given sequence, based on some PCFG. The inside part scores the subtrees from a parse tree and therefore subsequences probabilities given an PCFG. The outside part scores the probability of the complete parse tree for a full sequence.[28][29] CYK modifies the inside-outside scoring. Note that the term 'CYK algorithm' describes the CYK variant of the inside algorithm that finds an optimal parse tree for a sequence using a PCFG. It extends the actual CYK algorithm used in non-probabilistic CFGs.[9]

The inside algorithm calculates  probabilities for all

probabilities for all  of a parse subtree rooted at

of a parse subtree rooted at  for subsequence

for subsequence  . Outside algorithm calculates

. Outside algorithm calculates  probabilities of a complete parse tree for sequence x from root excluding the calculation of

probabilities of a complete parse tree for sequence x from root excluding the calculation of  . The variables α and β refine the estimation of probability parameters of an PCFG. It is possible to reestimate the PCFG algorithm by finding the expected number of times a state is used in a derivation through summing all the products of α and β divided by the probability for a sequence x given the model

. The variables α and β refine the estimation of probability parameters of an PCFG. It is possible to reestimate the PCFG algorithm by finding the expected number of times a state is used in a derivation through summing all the products of α and β divided by the probability for a sequence x given the model  . It is also possible to find the expected number of times a production rule is used by an expectation-maximization that utilizes the values of α and β.[28][29] The CYK algorithm calculates

. It is also possible to find the expected number of times a production rule is used by an expectation-maximization that utilizes the values of α and β.[28][29] The CYK algorithm calculates  to find the most probable parse tree

to find the most probable parse tree  and yields

and yields  .[9]

.[9]

Memory and time complexity for general PCFG algorithms in RNA structure predictions are  and

and  respectively. Restricting a PCFG may alter this requirement as is the case with database searches methods.

respectively. Restricting a PCFG may alter this requirement as is the case with database searches methods.

PCFG in homology search

Covariance models (CMs) are a special type of PCFGs with applications in database searches for homologs, annotation and RNA classification. Through CMs it is possible to build PCFG-based RNA profiles where related RNAs can be represented by a consensus secondary structure.[4][5] The RNA analysis package Infernal uses such profiles in inference of RNA alignments.[30] The Rfam database also uses CMs in classifying RNAs into families based on their structure and sequence information.[20]

CMs are designed from a consensus RNA structure. A CM allows indels of unlimited length in the alignment. Terminals constitute states in the CM and the transition probabilities between the states is 1 if no indels are considered.[9] Grammars in a CM are as follows:

-

- probabilities of pairwise interactions between 16 possible pairs

-

- probabilities of generating 4 possible single bases on the left

-

- probabilities of generating 4 possible single bases on the right

-

- bifurcation with a probability of 1

-

- start with a probability of 1

-

- end with a probability of 1

-

The model has 6 possible states and each state grammar includes different types of secondary structure probabilities of the non-terminals. The states are connected by transitions. Ideally current node states connect to all insert states and subsequent node states connect to non-insert states. In order to allow insertion of more than one base insert states connect to themselves.[9]

In order to score a CM model the inside-outside algorithms are used. CMs use a slightly different implementation of CYK. Log-odds emission scores for the optimum parse tree -  - are calculated out of the emitting states

- are calculated out of the emitting states  . Since these scores are a function of sequence length a more discriminative measure to recover an optimum parse tree probability score-

. Since these scores are a function of sequence length a more discriminative measure to recover an optimum parse tree probability score-  - is reached by limiting the maximum length of the sequence to be aligned and calculating the log-odds relative to a null. The computation time of this step is linear to the database size and the algorithm has a memory complexity of

- is reached by limiting the maximum length of the sequence to be aligned and calculating the log-odds relative to a null. The computation time of this step is linear to the database size and the algorithm has a memory complexity of  .[9]

.[9]

Example: Using evolutionary information to guide structure prediction

The KH-99 algorithm by Knudsen and Hein lays the basis of the Pfold approach to predicting RNA secondary structure.[16] In this approach the parameterization requires evolutionary history information derived from an alignment tree in addition to probabilities of columns and mutations. The grammar probabilities are observed from a training dataset.

Estimate column probabilities for paired and unpaired bases

In a structural alignment the probabilities of the unpaired bases columns and the paired bases columns are independent of other columns. By counting bases in single base positions and paired positions one obtains the frequencies of bases in loops and stems.

For basepair X and Y an occurrence of  is also counted as an occurrence of

is also counted as an occurrence of  . Identical basepairs such as

. Identical basepairs such as  are counted twice.

are counted twice.

Calculate mutation rates for paired and unpaired bases

By pairing sequences in all possible ways overall mutation rates are estimated. In order to recover plausible mutations a sequence identity threshold should be used so that the comparison is between similar sequences. This approach uses 85% identity threshold between pairing sequences. First single base positions differences -except for gapped columns- between sequence pairs are counted such that if the same position in two sequences had different bases X, Y the count of the difference is incremented for each sequence.

while

first sequence pair

second sequence pair

Calculate mutation rates. Letmutation of base X to base Y

Let

the negative of the rate of X mutation to other bases

the probability that the base is not paired.

For unpaired bases a 4 X 4 mutation rate matrix is used that satisfies that the mutation flow from X to Y is reversible:[31]

For basepairs a 16 X 16 rate distribution matrix is similarly generated.[32][33] The PCFG is used to predict the prior probability distribution of the structure whereas posterior probabilities are estimated by the inside-outside algorithm and the most likely structure is found by the CYK algorithm.[16]

Estimate alignment probabilities

After calculating the column prior probabilities the alignment probability is estimated by summing over all possible secondary structures. Any column C in a secondary structure  for a sequence D of length l such that

for a sequence D of length l such that  can be scored with respect to the alignment tree T and the mutational model M. The prior distribution given by the PCFG is

can be scored with respect to the alignment tree T and the mutational model M. The prior distribution given by the PCFG is  . The phylogenetic tree, T can be calculated from the model by maximum likelihood estimation. Note that gaps are treated as unknown bases and the summation can be done through dynamic programming.[34]

. The phylogenetic tree, T can be calculated from the model by maximum likelihood estimation. Note that gaps are treated as unknown bases and the summation can be done through dynamic programming.[34]

Assign production probabilities to each rule in the grammar

Each structure in the grammar is assigned production probabilities devised from the structures of the training dataset. These prior probabilities give weight to predictions accuracy.[17][28][29] The number of times each rule is used depends on the observations from the training dataset for that particular grammar feature. These probabilities are written in parenthesis in the grammar formalism and each rule will have a total of 100%.[16] For instance:

Predict the structure likelihood

Given the prior alignment frequencies of the data the most likely structure from the ensemble predicted by the grammar can then be computed by maximizing  through the CYK algorithm. The structure with the highest predicted number of correct predictions is reported as the consensus structure.[16]

through the CYK algorithm. The structure with the highest predicted number of correct predictions is reported as the consensus structure.[16]

Pfold improvements on the KH-99 algorithm

PCFG based approaches are desired to be scalable and general enough. Compromising speed for accuracy needs to as minimal as possible. Pfold addresses the limitations of the KH-99 algorithm with respect to scalability, gaps, speed and accuracy.[16]

- In Pfold gaps are treated as unknown. In this sense the probability of a gapped column equals that of an ungapped one.

- In Pfold the tree T is calculated prior to structure prediction through neighbor joining and not by maximum likelihood through the PCFG grammar. Only the branch lengths are adjusted to maximum likelihood estimates.

- An assumption of Pfold is that all sequences have the same structure. Sequence identity threshold and allowing a 1% probability that any nucleotide becomes another limit the performance deterioration due to alignment errors.

Protein sequence analysis

Whereas PCFGs have proved powerful tools for predicting RNA secondary structure, usage in the field of protein sequence analysis has been limited. Indeed, the size of the amino acid alphabet and the variety of interactions seen in proteins make grammar inference much more challenging.[35] As a consequence, most applications of formal language theory to protein analysis have been mainly restricted to the production of grammars of lower expressive power to model simple functional patterns based on local interactions.[36][37] Since protein structures commonly display higher-order dependencies including nested and crossing relationships, they clearly exceed the capabilities of any CFG.[35] Still, development of PCFGs allows expressing some of those dependencies and providing the ability to model a wider range of protein patterns.

One of the main obstacles in inferring a protein grammar is the size of the alphabet that should encode the 20 different amino acids. It has been proposed to address this by using physico-chemical properties of amino acids to reduce significantly the number of possible combinations of right side symbols in production rules: 3 levels of a quantitative property are utilised instead of the 20 amino acid types, e.g. small, medium or large van der Waals volume.[38] Based on such a scheme, PCFGs have been produced to generate both binding site [38] and helix-helix contact site descriptors.[39] A significant feature of those grammars is that analysis of their rules and parse trees can provide biologically meaningful information.[38][39]

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 Chomsky, Noam (1956). "Three models for the description of language.". IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 2: 113–124. doi:10.1109/TIT.1956.1056813.

- 1 2 Chomsky, Noam (137-167). "On certain formal properties of grammars". Information and Control 2: 2. doi:10.1016/S0019-9958(59)90362-6. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 Noam Chomsky, ed. (1957). Syntactic Structures. Mouton & Co. Publishers, Den Haag, Netherlands,.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eddy S. R. and Durbin R. (1994). "RNA sequence analysis using covariance models.". Nucleic Acids Research 22 (11): 2079–2088. doi:10.1093/nar/22.11.2079. PMC 308124. PMID 8029015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sakakibara Y., Brown, M. Hughey, R., Mian, I. S.; et al. (1994). "Stochastic context-free grammars for tRNA modelling.". Nucleic Acids Research 22 (23): 5112–5120. doi:10.1093/nar/22.23.5112.

- 1 2 Grat, L. 1995. (1995). "Automatic RNA secondary structure determination with stochastic context-free grammars.". In Rawlings, C., Clark, D., Altman, R., Hunter, L., Lengauer, T and Wodak, S. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology, AAAI Press: 236–144.

- 1 2 Lefebvre, F (1995). "An optimized parsing algorithm well suited to RNA folding". In Rawlings, C., Clark, D., Altman, R., Hunter, L., Lengauer, T and Wodak, S. Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. AAAI Press: 222–230.

- 1 2 Lefebvre, F. (143-153). "A grammar-based unification of several alignment and folding algorithms.". In States. D. J., Agarwal, P., Gaasterlan, T., Hunter, L and Smith R. F., eds., Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Systems for Molecular Biology. AAAI Press. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 R. Durbin, S. Eddy, A. Krogh, G. Mitchinson, ed. (1998). Biological sequence analysis : probabilistic models of proteins and nucleic acids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62971-3.

- ↑ Klein, Daniel; Manning, Christopher (2003). "Accurate Unlexicalized Parsing" (PDF). Proceedings of the 41st Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: 423–430.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dowell R and Eddy S. "Evaluation of several lightweight stochastic context-free grammars for RNA secondary structure prediction.". BMC Bioinformatics 5 (71). doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-71.

- 1 2 McCaskill JS. (1990). "The Equilibrium Partition Function and Base Pair Binding Probabilities for RNA Secondary Structure.". Biopolymers. 29 (6-7): 1105–19. doi:10.1002/bip.360290621. PMID 1695107.

- 1 2 Juan V, Wilson C. (1999). "RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Based on Free Energy and Phylogenetic Analysis.". J Mol Biol. 289: 935–947. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.2801.

- 1 2 Zuker M (2000). "Calculating Nucleic Acid Secondary Structure.". Curr Opin Struct Biol. 10: 303–310. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00088-9.

- 1 2 Mathews DH., Sabina J., Zuker M., Turner DH. (1999). "Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure.". J Mol Biol. . 288 (5): 911–940. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. PMID 10329189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 B. Knudsen and J. Hein. (2003). "Pfold: RNA secondary structure prediction using stochastic context-free grammars.". Nucleic Acids Research. 31 (13): 3423–3428. doi:10.1093/nar/gkg614. PMC 169020. PMID 12824339.

- 1 2 3 4 Knudsen B, Hein J (1999). "RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Using Stochastic Context-Free Grammars and Evolutionary History.". Bioinformatics 15 (6): 446–454. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/15.6.446. PMID 10383470.

- 1 2 Rivas E, Eddy SR (2001). "Noncoding RNA Gene Detection Using Comparative Sequence Analysis.". BMC Bioinformatics. 2 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-2-8. PMC 64605. PMID 11801179.

- 1 2 Holmes I, Rubin GM (2002). "Pairwise RNA Structure Comparison with Stochastic Context-Free Grammars.". In Pac Symp Biocomput 2002: 163–174. doi:10.1142/9789812799623_0016.

- 1 2 3 P.P. Gardner, J. Daub, J. Tate, B.L. Moore, I.H. Osuch, S. Griffiths-Jones, R.D. Finn, E.P. Nawrocki, D.L. Kolbe, S.R. Eddy, A. Bateman. (2010). "Rfam: Wikipedia, clans and the "decimal" release.". Nucleic Acids Research 2011. 39 (Database): D141–D145. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1129. PMC 3013711. PMID 21062808.

- 1 2 Yao Z, Weinberg Z, Ruzzo WL. (2006). "CMfinder-a covariance model based RNA motif finding algorithm.". Bioinformatics 22. (4): 445–452. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btk008. PMID 16357030.

- 1 2 Rabani M, Kertesz M, Segal E. (2008). "Computational prediction of RNA structural motifs involved in post-transcriptional regulatory processes.". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 14885–14890. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803169105.

- 1 2 3 Goodarzi H, Najafabadi HS, Oikonomou P, Greco TM, Fish L, Salavati R, Cristea IM, Tavazoie S. (2012). "Systematic discovery of structural elements governing stability of mammalian messenger RNAs.". Nature 485: 264–268. doi:10.1038/nature11013.

- 1 2 Sipser M. (1996). Introduction to Theory of Computation. Brooks Cole Pub Co.

- 1 2 Michael A. Harrison (1978). Introduction to Formal Language Theory. Addison-Wesley.

- 1 2 Hopcroft J.E., Ullman J.D. (1979). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation. Addison-Wesley.

- 1 2 Giegerich R. (2000). "Explaining and Controlling Ambiguity in Dynamic Programming.". In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Symposium on Combinatorial Pattern Matching 1848 Edited by: Giancarlo R, Sankoff D. Montréal, Canada: Springer-Verlag, Berlin.: 46–59.

- 1 2 3 4 Lari K. and Young, S. J. (1990). "The estimation of stochastic context-free grammars using the inside-outside algorithm". Computer Speech and Language 4: 35–56. doi:10.1016/0885-2308(90)90022-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Lari K and Young, S. J. (1991). "Applications of stochastic context-free grammars using the inside-outside algorithm.". Computer Speech and Language 5: 237–257. doi:10.1016/0885-2308(91)90009-F.

- 1 2 "Nawrocki E. P., and Eddy S. R." (2013). "Infernal 1.1:100-fold faster RNA homology searches.". Bioinformatics. 29 (22): 2933–2935. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509. PMC 3810854. PMID 24008419.

- 1 2 Tavaré S. (1986). "Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences.". Lectures on Mathematics in the Life Sciences. American Mathematical Society 17: 57–86.

- 1 2 Muse S.V. (1995). "Evolutionary analyses of DNA sequences subject to constraints of secondary structure.". Genetics. 139 (3): 1429–1439. PMC 1206468. PMID 7768450.

- 1 2 Schöniger M., von Haeseler A. (1994). "A stochastic model for the evolution of autocorrelated DNA sequences.". Mol Phylogenet Evol. 3 (3): 240–7. doi:10.1006/mpev.1994.1026.

- 1 2 J.K. Baker (1979). "Trainable grammars for speech recognition". In D. Klatt and J. Wolf, editors, Speech Communication Papers for the 97th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America 36 (20): 545–550.

- 1 2 Searls, D (2013). "Review: A primer in macromolecular linguistics". Biopolymers 99 (3): 203–217. doi:10.1002/bip.22101.

- ↑ Krogh, A; Brown, M; Mian, I; Sjolander, K; Haussler, D (1994). "Hidden Markov models in computational biology: Applications to protein modeling". J Mol Biol 235: 1501–1531. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1104. PMID 8107089.

- ↑ Sigrist, C; Cerutti, L; Hulo, N; Gattiker, A; Falquet, L; Pagni, M; Bairoch, A; Bucher, P (2002). "PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors". Brief Bioinform 3 (3): 265–274. doi:10.1093/bib/3.3.265. PMID 12230035.

- 1 2 3 Dyrka, W; Nebel, J-C (2009). "A Stochastic Context Free Grammar based Framework for Analysis of Protein Sequences". BMC Bioinformatics 10: 323. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-10-323.

- 1 2 Dyrka, W; Nebel J-C, Kotulska M (2013). "Probabilistic grammatical model of protein language and its application to helix-helix contact site classification". Algorithms for Molecular Biology 8: 31. doi:10.1186/1748-7188-8-31.

- ↑ Myers, G. (1995). "Approximately matching context-free languages". Information Processing Letters 54: 85–92. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(95)00007-Y.