North American P-51 Mustang

| P-51 Mustang | |

|---|---|

| |

| P-51 Mustangs of the 375th Fighter Squadron, Eighth Air Force mid-1944. | |

| Role | Fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| First flight | 26 October 1940 |

| Introduction | January 1942 (RAF) [1] |

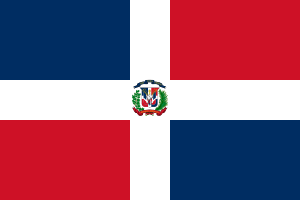

| Status | Retired from military service 1984 (Dominican Air Force)[2] |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces Royal Air Force Chinese Nationalist Air Force numerous others (see below) |

| Number built | More than 15,000[3] |

| Unit cost |

US$50,985 in 1945[4] |

| Variants | North American A-36 Rolls-Royce Mustang Mk.X Cavalier Mustang |

| Developed into | North American F-82 Twin Mustang Piper PA-48 Enforcer |

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II, the Korean War and other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in 1940 by North American Aviation (NAA) in response to a requirement of the British Purchasing Commission for license-built Curtiss P-40 fighters. The prototype NA-73X airframe was rolled out on 9 September 1940, 102 days after the contract was signed and first flew on 26 October.[5][6][7]

The Mustang was originally designed to use the Allison V-1710 engine of the P-40, which had limited high-altitude performance. It was first flown operationally by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a tactical-reconnaissance aircraft and fighter-bomber (Mustang Mk I). The addition of the Rolls-Royce Merlin to the P-51B/C model transformed the Mustang's performance at altitudes above 15,000 ft, matching or bettering that of the Luftwaffe's fighters.[8][nb 1] The definitive version, the P-51D, was powered by the Packard V-1650-7, a license-built version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin 60 series two-stage two-speed supercharged engine, and armed with six .50 caliber (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns.[10]

From late 1943, P-51Bs (supplemented by P-51Ds from mid-1944) were used by the USAAF's Eighth Air Force to escort bombers in raids over Germany, while the RAF's 2 TAF and the USAAF's Ninth Air Force used the Merlin-powered Mustangs as fighter-bombers, roles in which the Mustang helped ensure Allied air superiority in 1944.[11] The P-51 was also used by Allied air forces in the North African, Mediterranean and Italian theaters, and saw limited service against the Japanese in the Pacific War. During World War II, Mustang pilots claimed 4,950 enemy aircraft shot down.[nb 2]

At the start of the Korean War, the Mustang was the main fighter of the United Nations until jet fighters such as the F-86 took over this role; the Mustang then became a specialized fighter-bomber. Despite the advent of jet fighters, the Mustang remained in service with some air forces until the early 1980s. After World War II and the Korean War, many Mustangs were converted for civilian use, especially air racing, and increasingly, preserved and flown as historic warbird aircraft at airshows.

Design and development

In April 1940[13] the British government established a purchasing commission in the United States, headed by Sir Henry Self.[14] Self was given overall responsibility for Royal Air Force (RAF) production and research and development, and also served with Sir Wilfrid Freeman, the "Air Member for Development and Production". Self also sat on the British Air Council Sub-committee on Supply (or "Supply Committee") and one of his tasks was to organize the manufacturing and supply of American fighter aircraft for the RAF. At the time, the choice was very limited, as no U.S. aircraft then in production or flying met European standards, with only the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk coming close. The Curtiss-Wright plant was running at capacity, so P-40s were in short supply.[15]

North American Aviation (NAA) was already supplying its Harvard trainer to the RAF, but was otherwise underutilized. NAA President "Dutch" Kindelberger approached Self to sell a new medium bomber, the B-25 Mitchell. Instead, Self asked if NAA could manufacture the Tomahawk under license from Curtiss. Kindelberger said NAA could have a better aircraft with the same engine in the air sooner than establishing a production line for the P-40. The Commission stipulated armament of four .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, the Allison V-1710 liquid-cooled engine, a unit cost of no more than $40,000, and delivery of the first production aircraft by January 1941.[16] In March 1940, 320 aircraft were ordered by Sir Wilfred Freeman who had become the executive head of Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP), and the contract was promulgated on 24 April.[17]

The NA-73X, which was designed by a team led by lead engineer Edgar Schmued, followed the best conventional practice of the era, but included several new features.[nb 3] One was a wing designed using laminar flow airfoils which were developed co-operatively by North American Aviation and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). These airfoils generated very low drag at high speeds.[18] During the development of the NA-73X, a wind tunnel test of two wings, one using NACA 5-digit airfoils and the other using the new NAA/NACA 45–100 airfoils, was performed in the University of Washington Kirsten Wind Tunnel. The results of this test showed the superiority of the wing designed with the NAA/NACA 45–100 airfoils.[19][nb 4]

The other feature was a new radiator design that exploited the "Meredith Effect", in which heated air exited the radiator as a slight amount of jet thrust. Because NAA lacked a suitable wind tunnel to test this feature, it used the GALCIT 10 ft (3.0 m) wind tunnel at Caltech. This led to some controversy over whether the Mustang's cooling system aerodynamics were developed by NAA's engineer Edgar Schmued or by Curtiss, although NAA had purchased the complete set of P-40 and XP-46 wind tunnel data and flight test reports for US$56,000.[21] The NA-73X was also one of the first aircraft to have a fuselage lofted mathematically using conic sections; this resulted in the aircraft's fuselage having smooth, low drag surfaces.[22] To aid production, the airframe was divided into five main sections—forward, center, rear fuselage and two wing halves — all of which were fitted with wiring and piping before being joined.[22]

The prototype NA-73X was rolled out in September 1940, just 102 days after the order had been placed; it first flew on 26 October 1940, 149 days into the contract, an uncommonly short gestation period even during the war.[23] With test pilot Vance Breese at the controls[24]) the prototype handled well and accommodated an impressive fuel load. The aircraft's two-section, semi-monocoque fuselage was constructed entirely of aluminum to save weight. It was armed with four .30 in (7.62 mm) M1919 Browning machine guns, two in the wings and two mounted under the engine and firing through the propeller arc using gun synchronizing gear.

While the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) could block any sales it considered detrimental to the interests of the US, the NA-73 was considered to be a special case because it had been designed at the behest of the British. In September 1940 a further 300 NA-73s were ordered by MAP.[16] To ensure uninterrupted delivery Colonel Oliver P. Echols arranged with the Anglo-French Purchasing Commission to deliver the aircraft, and NAA gave two examples (41-038 and 41-039) to the USAAC for evaluation.[25][nb 5]

Operational history

U.S. operational service

Pre-war theory

Pre-war doctrine was based on the idea "the bomber will always get through".[27] Despite RAF and Luftwaffe experience, the USAAC still believed in 1942 that tightly packed formations of bombers would have so much firepower that they could fend off fighters on their own.[27] Fighter escort was low-priority, and when an escort fighter was planned in 1941, not considering what the nascent NA-73 design could be developed into – at a time when a heavy fighter with twin engines was considered to be most appropriate, like the Americans' own fast-flying Lockheed P-38 Lightning for existing types in the USAAF inventory – it would be a heavily up-armed "gunship" conversion of a strategic bomber that would get a chance to prove itself in action.[28] Additionally, a high-speed fighter with the range of a bomber was thought to be an engineering impossibility.[29]

Eighth Air Force bomber operations 1942–1943

The 8th Air Force started operations from Britain in August 1942. At first, because of the limited scale of operations, there was no conclusive evidence American doctrine was failing. In the 26 operations flown to the end of 1942, the loss rate had been under 2%.[30] This rate was better than the RAF's night efforts, and similar to the losses one would expect due to mechanical failure.

In January 1943, at the Casablanca Conference, the Allies formulated the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) plan for "round-the-clock" bombing – USAAF daytime operations complementing the RAF nighttime raids on industrial centers. In June 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the Pointblank Directive to destroy the Luftwaffe's capacity before the planned invasion of Europe, putting the CBO into full implementation. Following this, the 8th Air Force's heavy bombers conducted a series of deep-penetration raids into Germany, beyond the range of escort fighters.

German daytime fighter efforts were, at that time, focused on the Eastern Front and several other distant locations. Initial efforts by the 8th met limited and unorganized resistance, but with every mission the Luftwaffe moved more aircraft to the west and quickly improved their battle direction. The Schweinfurt–Regensburg mission in August lost 60 B-17s of a force of 376, the 14 October attack lost 77 of a force of 291—26% of the attacking force. Losses were so severe that long-range missions were called off.[31]

For the US, the very concept of self-defending bombers was called into question. But instead of abandoning daylight raids and turning to night bombing, as the RAF suggested, they chose other paths; at first it was believed that that a bomber with more guns (the Boeing YB-40) would be able to escort the bomber formations, but, when the concept proved to be unsuccessful, thoughts then turned to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning.[32] [nb 6] In early 1943 the USAAF also decided that the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and P-51B be considered for the role of a smaller escort fighter and, in July a report stated that the P-51B was "... the most promising plane ..." with an endurance of four hours 45 minutes with the standard internal fuel of 184 gallons plus 150 gallons carried externally.[34] In August a P-51B was fitted with an extra internal 85 gallon tank and, although there were problems with longitudinal stability and some compromises in performance with the tank full, it was decided that because the fuel from the fuselage tank would be used during the initial stages of a mission, the fuel tank would be fitted in all Mustangs destined for VIII Fighter Command.[35]

P-51 introduction

The P-51 Mustang was a solution to the clear need for an effective bomber escort. The Mustang was at least as simple as other aircraft of its era. It used a common, reliable engine and had internal space for a huge fuel load. With external fuel tanks, it could accompany the bombers all the way to Germany and back.[36] Enough P-51s became available to the 8th and 9th Air Forces in the winter of 1943–1944.

When the Pointblank offensive resumed in early 1944, matters had changed dramatically. The defence was initially layered, using the shorter range P-38s and P-47s to escort the bombers during the initial stages of the raid and then handing over to the P-51 when they turned for home. This provided continuous coverage during the entire raid. The Mustang was so clearly superior to earlier US designs that the Eighth Air Force began to steadily switch its fighter groups to the Mustang, first exchanging arriving P-47 groups for those of the 9th Air Force using P-51s, then gradually converting its Thunderbolt and Lightning groups. By the end of 1944, 14 of its 15 groups flew the Mustang.[37]

The Luftwaffe's twin-engine heavy fighters brought up to deal with the bombers proved to be easy prey for the Mustangs and had to be quickly withdrawn from combat. The Focke-Wulf Fw 190A, already suffering from poor high-altitude performance, was no match for the Mustang at the B-17's altitude, and when laden with heavy bomber-hunting weapons as a replacement for the more vulnerable twin-engined Zerstörer heavy fighters, it suffered badly. The Messerschmitt Bf 109G was on a more even footing at high altitudes, but this lightweight platform was even more greatly affected by increases in armament. The Mustang's much lighter armament, tuned for anti-fighter combat, allowed them to overcome both with relative ease.

The Luftwaffe initially adapted to the U.S. fighters by modifying their tactics. Instead of approaching in small groups in ad-hoc formations, they instead formed up en masse in front of the bomber's line of approach, and then attacked by making a single pass through the formation. Flying in close formation with the bombers, the P-51s had little time to react before the attackers were already running out of range.

Fighting the Luftwaffe

Major General James Doolittle, the new commander of the 8th Air Force as 1944 started, told the fighters in the late winter of 1944 to stop flying in formation with the bombers and instead attack the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found. The Mustang groups were sent in well before the bombers in a "fighter sweep" as a form of air supremacy action, intercepting German fighters, be they the usual single-engined Bf 109Gs or Fw 190As, or the twin-engined Zerstörer heavy fighters like the Bf 110Gs, wherever they were found to be forming up. As a result, the Luftwaffe lost 17% of its fighter pilots in just over a week, and the Allies were able to establish air superiority.[38] As Doolittle later noted, "Adolf Galland said that the day we took our fighters off the bombers and put them against the German fighters, that is, went from defensive to offensive, Germany lost the air war."[39]

The Luftwaffe's answer, especially to their Zerstörer twin-engined bomber destroyer units' evisceration by the USAAF, was the Gefechtsverband (battle formation). It consisted of a Sturmgruppe of heavily armed and armored Fw 190As escorted by two Begleitgruppen of light fighters, often Bf 109Gs, whose task was to keep the Mustangs away from the Sturmböcke Fw 190As attacking the bombers. This scheme was excellent in theory but difficult to apply in practice as the large German formation took a long time to assemble and was difficult to maneuver. It was often intercepted by the escorting P-51s using the newer "fighter sweep" tactics out ahead of the heavy bomber formations, breaking up the Gefechtsverband formations before reaching the bombers; when the Sturmgruppe was able to work as intended, the effects were devastating. With their engines and cockpits heavily armored, the Fw 190As attacked from astern and gun camera films show that these attacks were often pressed to within 100 yds (90 m).[40]

While not always able to avoid contact with the escorts, the threat of mass attacks and later the "company front" (eight abreast) assaults by armored Sturmgruppe Fw 190s brought an urgency to attacking the Luftwaffe wherever it could be found, either in the air or on the ground. Beginning in late February 1944, 8th Air Force fighter units began systematic strafing attacks on German airfields with increasing frequency and intensity throughout the spring with the objective of gaining air supremacy over the Normandy battlefield. In general these were conducted by units returning from escort missions but, beginning in March, many groups also were assigned airfield attacks instead of bomber support. The P-51, particularly with the advent of the K-14 Gyro gunsight and the development of "Clobber Colleges" for the training of fighter pilots in fall 1944, was a decisive element in Allied countermeasures against the Jagdverbände.

The numerical superiority of the USAAF fighters, superb flying characteristics of the P-51, and pilot proficiency helped cripple the Luftwaffe's fighter force. As a result, the fighter threat to US, and later British, bombers was greatly diminished by July 1944. The RAF, long proponents of night bombing for protection, were able to re-open daylight bombing in 1944 as a result of the destruction of the Luftwaffe. Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe during the war, was quoted as saying, "When I saw Mustangs over Berlin, I knew the jig was up."[41][42][43]

Beyond Pointblank

On 15 April 1944, VIII FC began Operation Jackpot, attacks on Luftwaffe fighter airfields. As the efficacy of these missions increased, the number of fighters at the German airbases fell to the point where they were no longer worthwhile targets. On 21 May, targets were expanded to include railways, locomotives and rolling stock used by the Germans to transport materiel and troops, in missions dubbed "Chattanooga".[44] The P-51 excelled at this mission, although losses were much higher on strafing missions than in air-to-air combat, partially because, like other fighters using liquid-cooled engines, the Mustang's coolant system could be punctured by small arms, unlike the air-cooled Double Wasp radials of its Republic P-47 Thunderbolt stablemates based in England, regularly tasked with ground strafing missions.

Given the overwhelming Allied air superiority, the Luftwaffe put its effort into the development of aircraft of such high performance that they could operate with impunity, but which also made bomber attack much more difficult, merely from the flight velocities they achieved. Foremost among these were the Messerschmitt Me 163B point-defense rocket interceptors, which started their operations with JG 400 near the end of July 1944, and the longer-endurance Messerschmitt Me 262A jet fighter, first flying with the Gruppe-strength Kommando Nowotny unit by the end of September 1944. In action, the Me 163 proved to be more dangerous to the Luftwaffe than to the Allies and was never a serious threat. The Me 262A was a serious threat, but attacks on their airfields neutralized them. The pioneering Junkers Jumo 004 axial-flow jet engines of the Me 262As needed careful nursing by their pilots and these aircraft were particularly vulnerable during takeoff and landing.[45] Lt. Chuck Yeager of the 357th Fighter Group was one of the first American pilots to shoot down an Me 262, which he caught during its landing approach. On 7 October 1944, Lt. Urban Drew of the 365th Fighter Group shot down two Me 262s that were taking off, while on the same day Lt. Col. Hubert Zemke, who had transferred to the Mustang equipped 479th Fighter Group, shot down what he thought was a Bf 109, only to have his gun camera film reveal that it may have been an Me 262.[46] On 25 February 1945, Mustangs of the 55th Fighter Group surprised an entire Staffel of Me 262As at takeoff and destroyed six jets.[47]

The Mustang also proved useful against the V-1s launched toward London. P-51B/Cs using 150 octane fuel were fast enough to catch the V-1 and operated in concert with shorter-range aircraft like advanced marks of the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Tempest.

By 8 May 1945,[48] the 8th, 9th and 15th Air Force's P-51 groups [nb 7] claimed some 4,950 aircraft shot down (about half of all USAAF claims in the European theater, the most claimed by any Allied fighter in air-to-air combat)[48] and 4,131 destroyed on the ground. Losses were about 2,520 aircraft.[49] The 8th Air Force's 4th Fighter Group was the top-scoring fighter group in Europe, with 1,016 enemy aircraft claimed destroyed. This included 550 claimed in aerial combat and 466 on the ground.[50]

In air combat, the top-scoring P-51 units (both of which exclusively flew Mustangs) were the 357th Fighter Group of the 8th Air Force with 565 air-to-air combat victories and the Ninth Air Force's 354th Fighter Group with 664, which made it one of the top scoring fighter groups. Martin Bowman reports that in the European Theater of Operations, Mustangs flew 213,873 sorties and lost 2,520 aircraft to all causes. The top Mustang ace was the USAAF's George Preddy, whose final tally stood at 26 and a third, 23 of which were scored with the P-51, when he was shot down and killed by friendly fire on Christmas Day 1944 during the Battle of the Bulge.[48]

In China and the Pacific Theater

In 1943, P-51B joined the American Volunteer Group. In early 1945, P-51C, D and K variants also joined the Chinese Nationalist Air Force. These Mustangs were provided to the 3rd, 4th and 5th Fighter Groups and used to attack Japanese targets in occupied areas of China. The P-51 became the most capable fighter in China while the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force used the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate against it.

The P-51 was a relative latecomer to the Pacific Theater. This was due largely to the need for the aircraft in Europe, although the P-38's twin-engine design was considered a safety advantage for long over-water flights. The first P-51s were deployed in the Far East later in 1944, operating in close-support and escort missions, as well as tactical photo reconnaissance. As the war in Europe wound down, the P-51 became more common: eventually, with the capture of Iwo Jima, it was able to be used as a bomber escort during Boeing B-29 Superfortress missions against the Japanese homeland.

The P-51 was often mistaken for the Japanese Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien in both China and Pacific because of its similar appearance.

Pilot observations

Chief Naval Test Pilot and C.O. Captured Enemy Aircraft Flight Capt. Eric Brown, CBE, DSC, AFC, RN, tested the Mustang at RAE Farnborough in March 1944, and noted, "The Mustang was a good fighter and the best escort due to its incredible range, make no mistake about it. It was also the best American dogfighter. But the laminar flow wing fitted to the Mustang could be a little tricky. It could not by any means out-turn a Spitfire [sic]. No way. It had a good rate-of-roll, better than the Spitfire, so I would say the plusses to the Spitfire and the Mustang just about equate. If I were in a dogfight, I'd prefer to be flying the Spitfire. The problem was I wouldn't like to be in a dogfight near Berlin, because I could never get home to Britain in a Spitfire!"[51]

The U.S Air Forces, Flight Test Engineering, assessed the Mustang B on 24 April 1944 "The rate of climb is good and the high speed in level flight is exceptionally good at all altitudes, from sea level to 40,000 feet. The airplane is very maneuverable with good controllability at indicated speeds to 400 MPH. The stability about all axes is good and the rate of roll is excellent, however, the radius of turn is fairly large for a fighter. The cockpit layout is excellent, but visibility is poor on the ground and only fair in level flight."[52]

Kurt Bühligen, the third-highest scoring German fighter pilot of World War II's Western Front (with 112 confirmed victories, three against Mustangs), later stated, "We would out-turn the P-51 and the other American fighters, with the Bf 109 or the FW 190. Their turn rate was about the same. The P-51 was faster than us but our munitions and cannon were better."[53][54]

Post-World War II

_F-51_Mustangs.jpg)

In the aftermath of World War II, the USAAF consolidated much of its wartime combat force and selected the P-51 as a "standard" piston-engine fighter, while other types, such as the P-38 and P-47, were withdrawn or given substantially reduced roles. As the more advanced (P-80 and P-84) jet fighters were introduced, the P-51 was also relegated to secondary duties.

In 1947, the newly formed USAF Strategic Air Command employed Mustangs alongside F-6 Mustangs and F-82 Twin Mustangs, due to their range capabilities. In 1948, the designation P-51 (P for pursuit) was changed to F-51 (F for fighter), and the existing F designator for photographic reconnaissance aircraft was dropped because of a new designation scheme throughout the USAF. Aircraft still in service in the USAF or Air National Guard (ANG) when the system was changed included: F-51B, F-51D, F-51K, RF-51D (formerly F-6D), RF-51K (formerly F-6K), and TRF-51D (two-seat trainer conversions of F-6Ds). They remained in service from 1946 through 1951. By 1950, although Mustangs continued in service with the USAF after the war, the majority of the USAF's Mustangs had become surplus to requirements and placed in storage, while some were transferred to the Air Force Reserve (AFRES) and the Air National Guard (ANG).

From the start of the Korean War, the Mustang once again proved useful. A substantial number of stored or in-service F-51Ds were shipped, via aircraft carriers, to the combat zone and were used by the USAF, and the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF). The F-51 was used for ground attack, fitted with rockets and bombs, and photo-reconnaissance, rather than being as interceptors or "pure" fighters. After the first North Korean invasion, USAF units were forced to fly from bases in Japan, and the F-51Ds, with their long range and endurance, could attack targets in Korea that short-ranged F-80 jets could not. Because of the vulnerable liquid cooling system, however, the F-51s sustained heavy losses to ground fire.[3] Due to its lighter structure, and a shortage of spare parts, the newer, faster F-51H was not used in Korea.

Mustangs continued flying with USAF and ROKAF fighter-bomber units on close support and interdiction missions in Korea until 1953, when they were largely replaced as fighter-bombers by USAF F-84s, and by United States Navy (USN) Grumman F9F Panthers. Other air forces and units using the Mustang included the Royal Australian Air Force's (RAAF)'s 77 Squadron, which flew Australian-built Mustangs as part of British Commonwealth Forces Korea. The Mustangs were replaced by Gloster Meteor F8s in 1951. The South African Air Force's (SAAF)'s 2 Squadron used U.S.-built Mustangs as part of the U.S. 18th Fighter Bomber Wing, and had suffered heavy losses by 1953, after which 2 Squadron converted to the F-86 Sabre.

F-51s flew in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard throughout the 1950s. The last American USAF Mustang was F-51D-30-NA AF Serial No. 44-74936, which was finally withdrawn from service with the West Virginia Air National Guard in late 1956 and retired to what was then called the Air Force Central Museum, although it was briefly reactivated to fly at the 50th anniversary of the Air Force Aerial Firepower Demonstration at the Air Proving Ground, Eglin AFB, Florida, on 6 May 1957.[55] This aircraft, painted as P-51D-15-NA Serial No. 44-15174, is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, in Dayton, Ohio.[56]

The final withdrawal of the Mustang from USAF dumped hundreds of P-51s onto the civilian market. The rights to the Mustang design were purchased from North American by the Cavalier Aircraft Corporation, which attempted to market the surplus Mustang aircraft in the U.S. and overseas. In 1967 and again in 1972, the USAF procured batches of remanufactured Mustangs from Cavalier, most of them destined for air forces in South America and Asia that were participating in the Military Assistance Program (MAP). These aircraft were remanufactured from existing original F-51D airframes but were fitted with new V-1650-7 engines, a new radio fit, tall F-51H-type vertical tails, and a stronger wing that could carry six 0.50 in (13 mm) machine guns and a total of eight underwing hardpoints. Two 1,000 lb (454 kg) bombs and six 5 in (127 mm) rockets could be carried. They all had an original F-51D-type canopy, but carried a second seat for an observer behind the pilot. One additional Mustang was a two-seat dual-control TF-51D (67-14866) with an enlarged canopy and only four wing guns. Although these remanufactured Mustangs were intended for sale to South American and Asian nations through the MAP, they were delivered to the USAF with full USAF markings. They were, however, allocated new serial numbers (67-14862/14866, 67-22579/22582 and 72-1526/1541).[56]

The last U.S. military use of the F-51 was in 1968, when the U. S. Army employed a vintage F-51D (44-72990) as a chase aircraft for the Lockheed YAH-56 Cheyenne armed helicopter project. This aircraft was so successful that the Army ordered two F-51Ds from Cavalier in 1968 for use at Fort Rucker as chase planes. They were assigned the serials 68-15795 and 68-15796. These F-51s had wingtip fuel tanks and were unarmed. Following the end of the Cheyenne program, these two chase aircraft were used for other projects. One of them (68-15795) was fitted with a 106 mm recoilless rifle for evaluation of the weapon's value in attacking fortified ground targets.[57] Cavalier Mustang 68-15796 survives at the Air Force Armament Museum, Eglin AFB, Florida, displayed indoors in World War II markings.

The F-51 was adopted by many foreign air forces and continued to be an effective fighter into the mid-1980s with smaller air arms. The last Mustang ever downed in battle occurred during Operation Power Pack in the Dominican Republic in 1965, with the last aircraft finally being retired by the Dominican Air Force (FAD) in 1984.[58]

Non-U.S. service

The Mustang was developed for the RAF, who were its first users. After World War II, the P-51 Mustang served in the air arms of more than 25 nations.[11] During the war, a Mustang cost about $51,000,[4] while many hundreds were sold postwar for the nominal price of one dollar to signatories of the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, ratified in Rio de Janeiro in 1947.[59]

The following is a list of some of the countries that used the P-51 Mustang.

.jpg)

- In November 1944, 3 Squadron RAAF became the first Royal Australian Air Force unit to use Mustangs. At the time of its conversion from the P-40 to the Mustang the squadron was based in Italy with the RAF's First Tactical Air Force.

- 3 Squadron was renumbered 4 Squadron after returning to Australia from Italy and converted to P-51Ds. Several other Australian or Pacific based squadrons converted to either CAC-built Mustangs or to imported P-51Ks from July 1945, having been equipped with P-40s or Boomerangs for wartime service; these units were: 76, 77, 82, 83, 84 and 86 Squadrons. Only 17 Mustangs reached the RAAF's First Tactical Air Force front line squadrons by the time World War II ended in August 1945.

- 76, 77 and 82 Squadrons were formed into 81 Fighter Wing of the British Commonwealth Air Force (BCAIR) which was part of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) stationed in Japan from February 1946. 77 Squadron used its P-51s extensively during the first months of the Korean War, before converting to Gloster Meteor jets.[60]

- Five reserve units from the Citizen Air Force (CAF) also operated Mustangs. 21 "City of Melbourne" Squadron, based in the state of Victoria; 22 "City of Sydney" Squadron, based in New South Wales; 23 "City of Brisbane" Squadron, based in Queensland; 24 "City of Adelaide" Squadron, based in South Australia; and 25 "City of Perth" Squadron, based in Western Australia; all of these units were equipped with CAC Mustangs, rather than P-51D or Ks. The last Mustangs were retired from these units in 1960 when CAF units adopted a non-flying role.[61]

- Nine Cavalier F-51D (including the two TF-51s) were given to Bolivia, under a program called Peace Condor.[62]

- Canada had five squadrons equipped with Mustangs during World War II. RCAF 400, 414 and 430 squadrons flew Mustang Mk Is (1942–1944), and 441 and 442 Squadrons flew Mustang Mk IIIs and IVAs in 1945. Postwar, a total of 150 Mustang P-51Ds were purchased and served in two regular (416 "Lynx" and 417 "City of Windsor") and six auxiliary fighter squadrons (402 "City of Winnipeg", 403 "City of Calgary", 420 "City of London", 424 "City of Hamilton", 442 "City of Vancouver" and 443 "City of New Westminster"). The Mustangs were declared obsolete in 1956, but a number of special-duty versions served on into the early 1960s.

- The Chinese Nationalist Air Force obtained the P-51 during the late Sino-Japanese War to fight against the Japanese. After the war, Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist government used the planes against insurgent Communist forces. The Nationalists retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Pilots supporting Chiang brought most of the Mustangs with them, where the aircraft became part of the island's defence arsenal.

People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China- The Communist Chinese captured 39 P-51s from the Nationalists while they were retreating to Taiwan.[62]

Costa Rica

Costa Rica- The Costa Rica Air Force flew four P-51Ds from 1955 to 1964.[62]

Cuba

Cuba- In November 1958, three US-registered civilian P-51D Mustangs were illegally flown separately from Miami to Cuba, on delivery to the rebel forces of the 26th of July Movement, then headed by Fidel Castro during the Cuban Revolution. One of the Mustangs was damaged during delivery, and none of them were used operationally. After the success of the revolution in January 1959, with other rebel aircraft plus those of the existing Cuban government forces, they were adopted into the Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria. Due to increasing U.S. restrictions, lack of spares and maintenance experience, they never achieved operational status. At the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the two intact Mustangs were already effectively grounded at Campo Columbia and at Santiago. After the failed invasion, they were placed on display with other symbols of "revolutionary struggle", and one remains on display at the Museo del Aire.[63][64][65]

Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic- The Dominican Republic (FAD) was the largest Latin American air force to employ the P-51D, with six aircraft acquired in 1948, 44 ex-Swedish F-51Ds purchased in 1948 and a further Mustang obtained from an unknown source.[66] It was the last nation to have any Mustangs in service, with some remaining in use as late as 1984. Nine of the final 10 aircraft were sold back to American collectors in 1988.[62]

El Salvador

El Salvador- The FAS purchased five Cavalier Mustang IIs (and one dual control Cavalier TF-51) that featured wingtip fuel tanks to increase combat range and up-rated Merlin engines. Seven P-51D Mustangs were also in service.[62] They were used during the 1969 Soccer War against Honduras, the last time the P-51 was used in combat. One of them, FAS-404, was shot down by a F4U-5 flown by Cap. Fernando Soto in the last aerial combat between piston engine fighters in the world.[67]

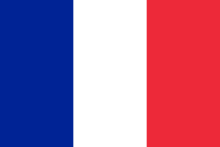

France

France- In late 1944, the first French unit began its transition to reconnaissance Mustangs. In January 1945, the Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 2/33 of the French Air Force took their F-6Cs and F-6Ds over Germany on photographic mapping missions. The Mustangs remained in service until the early 1950s, when they were replaced by jet fighters.[62]

.svg.png) Germany

Germany- Several P-51s were captured by the Luftwaffe as Beuteflugzeug ("captured aircraft") following crash landings. These aircraft were subsequently repaired and test-flown by the Zirkus Rosarius, or Rosarius Staffel, the official Erprobungskommando of the Luftwaffe High Command, for combat evaluation at Göttingen. The aircraft were repainted with German markings and bright yellow nose and belly for identification. A number of P-51B/P-51Cs – including examples marked with Luftwaffe Geschwaderkennung codes T9+CK, T9+FK, T9+HK and T9+PK (with the "T9" prefix not known to be officially assigned to any existing Luftwaffe formation from their own records, outside of the photos of Zirkus Rosarius-flown aircraft) — with a total of three captured P-51Ds also flown by the unit.[68] Some of these P-51s were found by Allied forces at the end of the war; others crashed during testing.[69] The Mustang is also listed in the appendix to the novel KG 200 as having been flown by the German secret operations unit KG 200, which tested, evaluated and sometimes clandestinely operated captured enemy aircraft during World War II.[70]

.jpg)

- The Fuerza Aérea Guatemalteca (FAG) had 30 P-51D Mustangs in service from 1954 to the early 1970s.[62]

Haiti

Haiti- Haiti had four P-51D Mustangs when President Paul Eugène Magloire was in power from 1950-1956, with the last retired in 1973–74 and sold for spares to the Dominican Republic.[71]

- Indonesia acquired some P-51Ds from the departing Netherlands East Indies Air Force in 1949 and 1950. The Mustangs were used against Commonwealth (RAF, RAAF and RNZAF) forces during the Indonesian confrontation in the early 1960s. The last time Mustangs were deployed for military purposes was a shipment of six Cavalier II Mustangs (without tip tanks) delivered to Indonesia in 1972–1973, which were replaced in 1976.[72][73]

Israel

Israel- A few P-51 Mustangs were illegally bought by Israel in 1948, crated and smuggled into the country as agricultural equipment for use in the War of Independence (1948) and quickly established themselves as the best fighter in the Israeli inventory.[74] Further aircraft were bought from Sweden, and were replaced by jets at the end of the 1950s, but not before the type was used in the Suez Crisis, Operation Kadesh (1956). Reputedly, during this conflict, one Israeli pilot literally cut communications between Suez City and the Egyptian front lines by using his Mustang's propeller on the telephone wires.[75]

Italy

Italy- Italy was a postwar operator of P-51Ds; deliveries were slowed by the Korean war, but between September 1947 and January 1951, by MDAP count, 173 examples were delivered. They were used in all the AMI fighter units: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 51 Stormo (Wing), and some in schools and experimental units. Considered a "glamorous" fighter, P-51s were even used as personal aircraft by several Italian commanders. Some restrictions were placed on its use due to unfavorable flying characteristics. Handling had to be done with much care when fuel tanks were fully utilized and several aerobatic maneuvers were forbidden. Overall, the P-51D was highly rated even compared to the other primary post-war fighter in Italian service, the Supermarine Spitfire, partly because these P-51Ds were in very good condition in contrast to all other Allied fighters supplied to Italy. Phasing out of the Mustang began in summer 1958.[76]

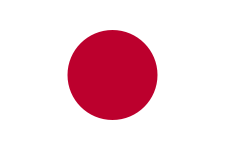

Japan

Japan- The P-51C-11-NT Evalina, marked as "278" (former USAAF serial: 44-10816) and flown by 26th FS, 51st FG, was hit by gunfire on 16 January 1945 and belly-landed on Suchon Airfield in China, which was held by the Japanese. The Japanese repaired the aircraft, roughly applied Hinomaru roundels and flew the aircraft to the Fussa evaluation centre (now Yokota Air Base) in Japan.[62]

.jpg)

- The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force received 40 P-51Ds and flew them during the Indonesian National Revolution particularly the two 'politionele acties': Operatie Product in 1947 and Operatie Kraai in 1949.[77] When the conflict was over, Indonesia received some of the ML-KNIL Mustangs.[62]

Nicaragua

Nicaragua- Fuerza Aerea de Nicaragua (GN) purchased 26 P-51D Mustangs from Sweden in 1954 and later received 30 P-51D Mustangs from the U.S. together with two TF-51 models from MAP after 1954. All aircraft of this type were retired from service by 1964.[62]

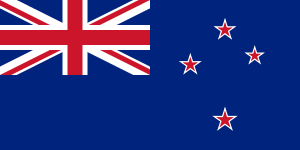

New Zealand

New Zealand- New Zealand ordered 370 P-51 Mustangs to supplement its Vought F4U Corsairs in the Pacific Ocean Areas theatre. Scheduled deliveries were for an initial batch of 30 P-51Ds, followed by 137 more P-51Ds and 203 P-51Ms.[78] The original 30 were being shipped as the war ended in August 1945; these were stored in their packing cases and the order for the additional Mustangs was cancelled. In 1951 the stored Mustangs entered service in 1 (Auckland), 2(Wellington), 3 (Canterbury) and 4 (Otago) squadrons of the Territorial Air Force (TAF). The Mustangs remained in service until they were prematurely retired in August 1955 following a series of problems with undercarriage and coolant system corrosion problems. Four Mustangs served on as target tugs until the TAF was disbanded in 1957.[78] RNZAF pilots in the Royal Air Force also flew the P-51, and at least one New Zealand pilot scored victories over Europe while on loan to a USAAF P-51 squadron.

- The Philippines acquired 103 P-51D Mustangs after World War II. These became the backbone of the postwar Philippine Army Air Corps and Philippine Air Force and were used extensively during the Huk campaign, fighting against Communist insurgents.

- Mustangs were also the first aircraft of the Philippine air demonstration squadron, which was formed in 1953 and given the name "The Blue Diamonds" the following year.[79] The Mustangs were replaced by 56 F-86 Sabres in the late 1950s, but some were still in service for COIN roles up to the early 1980s.

Poland

Poland- During World War II, five Polish Air Force in Great Britain squadrons used Mustangs. The first Polish unit equipped (7 June 1942) with Mustang Mk Is was "B" Flight of 309 "Ziemi Czerwieńskiej" Squadron[nb 8] (an Army Co-Operation Command unit), followed by "A" Flight in March 1943. Subsequently, 309 Squadron was redesignated a fighter/reconnaissance unit and became part of Fighter Command. On 13 March 1944, 316 "Warszawski" Squadron received their first Mustang Mk IIIs; rearming of the unit was completed by the end of April. By 26 March 1943, 306 "Toruński" Sqn and 315 "Dębliński" Sqn received Mustangs Mk IIIs (the whole operation took 12 days). On 20 October 1944, Mustang Mk Is in No. 309 Squadron were replaced by Mk IIIs. On 11 December 1944, the unit was again renamed, becoming 309 Dywizjon Myśliwski "Ziemi Czerwieńskiej" or 309 "Land of Czerwien" Polish Fighter Squadron.[80] In 1945, 303 "Kościuszko" Sqn received 20 Mustangs Mk IV/Mk IVA replacements. Postwar, between 6 December 1946 and 6 January 1947, all five Polish squadrons equipped with Mustangs were disbanded. Poland returned approximately 80 Mustangs Mk IIIs and 20 Mustangs Mk IV/IVAs to the RAF, which transferred them to the U.S. government.[81]

Somalia

Somalia- The Somalian Air Force operated eight P-51Ds in post-World War II service.[82]

- No.5 Squadron South African Air Force operated a number of Mustang Mk IIIs (P-51B/C) and Mk IVs (P-51D/K) in Italy during World War II, beginning in September 1944 when the squadron converted to the Mustang Mk III from Kittyhawks. The Mk IV and Mk IVA came into SA service in March 1945. These aircraft were generally camouflaged in the British style, having been drawn from RAF stocks; all carried RAF serial numbers and were struck off charge and scrapped in October 1945. In 1950, 2 Squadron SAAF was supplied with F-51D Mustangs by the United States for Korean War service. The type performed well in South African hands before being replaced by the F-86 Sabre in 1952 and 1953.[62]

- Within a month of the outbreak of the Korean War, 10 F-51D Mustangs were provided to the badly depleted Republic of Korea Air Force as a part of the Bout One Project. They were flown by both South Korean airmen, several of whom were veterans of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy air services during World War II, as well as by U.S. advisers led by Major Dean Hess. Later, more were provided both from U.S. and from South African stocks, as the latter were converting to F-86 Sabres. They formed the backbone of the South Korean Air Force until they were replaced by Sabres.[62]

- It also served with the ROKAF Black Eagles aerobatic team, until retired 1954.

- Sweden's Flygvapnet first recuperated four of the P-51s (two P-51Bs and two early P-51Ds) that had been diverted to Sweden during missions over Europe. In February 1945, Sweden purchased 50 P-51Ds designated J 26, which were delivered by American pilots in April and assigned to the F 16 wing at Uppsala as interceptors. In early 1946, the F 4 wing at Östersund was equipped with a second batch of 90 P-51Ds. A final batch of 21 Mustangs was purchased in 1948. In all, 161 J 26s served in the Swedish Air Force during the late 1940s. About 12 were modified for photo reconnaissance and re-designated S 26. Some of these aircraft participated in the secret Swedish mapping of new Soviet military installations at the Baltic coast in 1946–47 (Operation Falun), an endeavour that entailed many intentional violations of Soviet airspace. However, the Mustang could outdive any Soviet fighter of that era, so no S 26s were lost in these missions.[83] The J 26s were replaced by De Havilland Vampires around 1950. The S 26s were replaced by S 29Cs in the early 1950s.[62]

- Switzerland

- The Swiss Air Force operated a few USAAF P-51s that had been impounded by Swiss authorities during World War II after the pilots were forced to land in neutral Switzerland. After the war, Switzerland also bought 130 P-51s for $4,000 each. They served until 1958.[62]

- United Kingdom

- The RAF was the first air force to operate the Mustang. As the first Mustangs were built to British requirements, these aircraft used factory numbers and were not P-51s; the order comprised 320 NA-73s, followed by 300 NA-83s, all of which were designated North American Mustang Mark I by the RAF.[84] The first RAF Mustangs diverted from American orders were 93 P-51s, designated Mark IA, followed by 50 P-51As used as Mustang Mk IIs.[85]

- The first Mustang Mk Is entered service in January 1942, the first unit being 26 Squadron RAF.[86] Due to poor high-altitude performance, the Mustangs were used by Army Co-operation Command, rather than Fighter Command, and were used for tactical reconnaissance and ground-attack duties. On 27 July 1942, 16 RAF Mustangs undertook their first long-range reconnaissance mission over Germany. During the Dieppe Raid (19 August 1942) four British and Canadian Mustang squadrons, including 26 Squadron saw action. By 1943–1944, British Mustangs were used extensively to seek out V-1 flying bomb sites. The final RAF Mustang Mk I and Mustang Mk II aircraft were struck off charge in 1945.

- The RAF also operated 308 P-51Bs and 636 P-51Cs[87] which were known in RAF service as Mustang Mk IIIs; the first units converted to the type in late 1943 and early 1944. Mustang Mk III units were operational until the end of World War II, though many units had already converted to the Mustang Mk IV and Mk IVAs (828 in total, comprising 282 P-51D-NAs or Mk IVs, and 600 P-51Ks or Mk IVA).[88] As the Mustang was a Lend-Lease type, all aircraft still on RAF charge at the end of the war were either returned to the USAAF "on paper" or retained by the RAF for scrapping. The final Mustangs were retired from RAF use in 1947.[62]

- USSR

- The Soviet Union received at least 10 early-model ex-RAF Mustang Mk Is and tested but found them to "under-perform" compared to contemporary USSR fighters, relegating them to training units. Later Lend-Lease deliveries of the P-51B/C and D series, along with other Mustangs abandoned in Russia after the famous "shuttle missions", were repaired and used by the Soviet Air Force but not in front-line service.[89]

- Uruguay

- The Uruguayan Air Force (FAU) used 25 P-51D Mustangs from 1950 to 1960; some were subsequently sold to Bolivia.[62]

P-51s and civil aviation

Many P-51s were sold as surplus after the war, often for as little as $1,500. Some were sold to former wartime fliers or other aficionados for personal use, while others were modified for air racing.[90] One of the most significant Mustangs involved in air racing was a surplus P-51C-10-NT (44-10947) purchased by film stunt pilot Paul Mantz. The aircraft was modified by creating a "wet wing", sealing the wing to create a giant fuel tank in each wing, which eliminated the need for fuel stops or drag-inducing drop tanks. This Mustang, named "Blaze of Noon" after the film Blaze of Noon, came in first in the 1946 and 1947 Bendix Air Races, second in the 1948 Bendix, and third in the 1949 Bendix. He also set a U.S. coast-to-coast record in 1947. The Mantz Mustang was sold to Charles F. Blair Jr (future husband of Maureen O'Hara) and renamed Excalibur III. Blair used it to set a New York-to-London (c. 3,460 mi/5,568 km) record in 1951: 7h 48min from takeoff at Idlewild to overhead London Airport. Later that same year, he flew from Norway to Fairbanks, Alaska, via the North Pole (c. 3,130 mi/5,037 km), proving that navigation via sun sights was possible over the magnetic north pole region. For this feat, he was awarded the Harmon Trophy, and the Air Force was forced to change its thoughts on a possible Soviet air strike from the north. This Mustang now resides in the National Air and Space Museum at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.[91]

The most prominent firm to convert Mustangs to civilian use was Trans-Florida Aviation, later renamed Cavalier Aircraft Corporation, which produced the Cavalier Mustang. Modifications included a taller tailfin and wingtip tanks. A number of conversions included a Cavalier Mustang specialty: a "tight" second seat added in the space formerly occupied by the military radio and fuselage fuel tank.

In 1958, 78 surviving RCAF Mustangs were retired from service's inventory and were ferried by Lynn Garrison an RCAF pilot, from their varied storage locations to Canastota, New York, where the American buyers were based. In effect, Garrison flew each of the surviving aircraft at least once. These aircraft make up a large percentage of the aircraft presently flying worldwide.[92]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the United States Department of Defense wished to supply aircraft to South American countries and later Indonesia for close air support and counter insurgency, it turned to Cavalier to return some of their civilian conversions back to updated military specifications.

In the 21st century, a P-51 can command a price of more than $1 million, even for only partially restored aircraft.[92] There were 204 privately owned P-51s in the U.S. on the FAA registry in 2011,[93] most of which are still flying, often associated with organizations such as the Commemorative Air Force (formerly the Confederate Air Force).[94]

In May 2013, Doug Matthews set an altitude record of 42,568 ft (12,975 m) in a P 51 named "The Rebel,” for piston powered aircraft weighing 3,000 to 6,000 kg (6,600 to 13,200 lb).[95] Mathews departed from a grass runway at Florida's Indiantown airport and flew “The Rebel” over Lake Okeechobee. He set world records for time to reach altitudes of 9,000 m (30,000 ft), 18 minutes, and 12,000 m (39,000 ft), 31 minutes. He achieved a new height record of 40,100 ft (12,200 m) in level flight and a 42,500 ft (13,000 m) maximum altitude.[96][97] The previous record of 36,902 ft (11,248 m) had stood since 1954.

Incidents

- On June 9, 1973 William Penn Patrick (43) a certified pilot, and his passenger, Christian Hagert, died when Patrick's privately owned P-51 Mustang crashed in Lakeport, California.[98][99]

- On September 16, 2011 The Galloping Ghost, a modified P-51 piloted by Jimmy Leeward of Ocala, Florida, crashed during an air race in Reno, Nevada. Leeward and at least nine people on the ground were killed when the racer suddenly crashed near the edge of the grandstand.[100]

- On October 23, 2013, "Galveston Gal," P-51D no. 44-73458 N4151D, piloted by 51-year-old pilot Keith Hibbett of Denton accompanied by his 66-year-old passenger John Stephen Busby, who was visiting from the United Kingdom, were killed when the aircraft crashed in about four feet of water off the coast of Galveston, Texas. Busby was celebrating his 41st wedding anniversary.[101][102]

- On July 4, 2014, John Early and Michael Schlarb were killed when Early's P-51 crashed shortly after takeoff in Durango County, Colorado.[103]

Variants

Production

- Source: U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909[104]

- NA.73X

- Prototype, one built

- A-36 Apache / A-36 Invader

- Order in FY 42 as a dive bomber by the AAF. Initially named Apache; also known as Invader but renamed Mustang (See A-36 article) . 500 ea.

- P-51

- 57 taken over by USAAF from RAF Mustang Mk IA contract. Fitted with Allison V-1710-39 engines.

- P-51A

- 310 built at Inglewood, California, 50 delivered to RAF as Mustang Mk II.

- P-51B

- 1,988 built at Inglewood. First production version to be equipped with the Merlin engine.

- P-51C

- 1,750 built at Dallas, Texas

- TP-51C

- Field modification to create dual-control variant; at least five known built during World War II for training and VIP transport[105]

- P-51D

- A total of 8,156 were built: 6,502 at Inglewood, 1,454 at Dallas.

- XP-51F

- lightweight version; three built

- XP-51G

- lightweight version; five-bladed propeller. Two built

- P-51H

- 555 built at Inglewood

- XP-51J

- Allison-engined light weight development. Two built

- P-51K

- 1,500 built at Dallas, Texas

- P-51L

- cancelled

- P-51M

- As P-51H. One built at Dallas Contract terminated.

- Mustang Mk.I

- 620 built at Inglewood

- Mustang Mk.IA

- 150 built at Inglewood

- 57 were retained by USAAF to become P-51s, further two became XP-51Bs

- Mustang Mk.II

- 50 P-51A delivered to RAF

- Mustang Mk.III

- 852 P-51B/C delivered to RAF under Lend Lease

- Mustang Mk.IV

- 281 P-51D delivered to RAF under Lend Lease

- Mustang Mk.IVA

- 595 P-51K delivered to RAF under Lend Lease

- Rolls-Royce Mustang Mk.X

- Five prototype conversions only – two Mustang Mk.I airframes were initially trial fitted with Rolls-Royce Merlin 65 engines in mid-late 1942, in order to test the performance of the aircraft with a powerplant better adapted to medium/high altitudes. The successful conversion of the Packard V-1650 Merlin-powered NAA P-51B/C equivalent rendered this experiment as superfluous. Although the conversions were highly successful, the planned production of 500 examples was cancelled.[106]

- Commonwealth CA-17 Mustang Mk.20

- 80 Australian assembled P-51Ds, (100 delivered as kits but only 80 assembled).

- Commonwealth CA-18 Mustang Mk. 21, Mk.22 and Mk.23

- Licence production of 120 of the P-51D model, of which the Mk.21 and Mk.22 used the American-built Packard V-1650-3 or V-1650-7 and the Mk.23, which followed the Mk.21, was powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 or Merlin 70 engines. 170 were ordered but only 120 were built.

- Total number built

- 15,586

Survivors

Specifications (P-51D Mustang)

Data from Erection and Maintenance Manual for P-51D and P-51K.[107] P-51 Tactical Planning Characteristics & Performance Chart,[108] The Great Book of Fighters,[109] and Quest for Performance[110]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 32 ft 3 in (9.83 m)

- Wingspan: 37 ft 0 in (11.28 m)

- Height: 13 ft 4½ in (4.08 m:tail wheel on ground, vertical propeller blade.)

- Wing area: 235 sq ft (21.83 m²)

- Airfoil: NAA/NACA 45-100 / NAA/NACA 45-100

- Empty weight: 7,635 lb (3,465 kg)

- Loaded weight: 9,200 lb (4,175 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 12,100 lb (5,490 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Packard V-1650-7 liquid-cooled V-12, with a 2 stage intercooled supercharger, 1,490 hp (1,111 kW) at 3,000 rpm;[111] 1,720 hp (1,282 kW) at WEP

- Propellers: constant-speed, variable-pitch Hamilton Standard, propeller

- Propeller diameter: 11 ft 2 in (3.40 m)

- *Maximum fuel capacity: 419 US gal (349 imp gal; 1,590 l)

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0163

- Drag area: 3.80 sqft (0.35 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 5.83

Performance

- Maximum speed: 437 mph (380 kn, 703 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m)

- Cruise speed: 362 mph (315 kn, 580 km/h)

- Stall speed: 100 mph (87 kn, 160 km/h)

- Range: 1,650 mi (1,434 nmi, 2,755 km) with external tanks

- Service ceiling: 41,900 ft (12,800 m)

- Rate of climb: 3,200 ft/min (16.3 m/s)

- Wing loading: 39 lb/sqft (192 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.18 hp/lb (300 W/kg)

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 14.6

- Recommended Mach limit 0.8

Armament

- Guns: 6 × 0.50 caliber (12.7mm) AN/M2 Browning machine guns with 1,840 total rounds (380 rounds for each on the inboard pair, and 270 rounds for each of the outer two pair)

- Rockets: 6 or 10 × 5.0 in (127 mm) T64 H.V.A.R rockets (P-51D-25, P-51K-10 on)[nb 10]

- Bombs: 1,000 lb (453 kg) total on two wing hardpoints

Notable appearances in media

- Battle Hymn (1956) is based on the real-life experiences of Lt Col Dean E. Hess, USAF (played by Rock Hudson) and his cadre of U.S. Air Force instructors in the early days of the Korean War, training the pilots of the Republic of Korea Air Force and leading them during their first missions in F-51D/F-51Ks.

- Goodbye, Mickey Mouse (1982) is a historical novel by Len Deighton. Set in Britain in early 1944 it tells the story of the 220th Fighter Group of the U.S. Eighth Air Force flying P-51s in the lead up to the Allied invasion of Europe. The Group is based at the fictional Steeple Thaxted airfield in Norfolk.

- The Tuskegee Airmen (1995), the story of how a group of African-American pilots overcame racist opposition to become one of the finest U.S. fighter groups in World War II, flying P-51s, although the 99th Squadron would have used P-40s and P-39s during their North African stint.[115]

- Red Tail Reborn (2007), the story behind the restoration of a flying memorial aircraft.

- Red Tails (2012) is a George Lucas produced film about the Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group, featuring P-51 Mustangs in their role as escort fighters.[116]

Scale replicas

As indicative of the iconic nature of the P-51, manufacturers within the hobby industry have created scale plastic model kits of the P-51 Mustang, with varying degrees of detail and skill levels. The aircraft have also been the subject of numerous scale flying replicas.[117] Aside from the popular R/C-controlled aircraft, several kitplane manufacturers offer ½, ⅔, and ¾-scale replicas capable of comfortably seating one (or even two) and offering high performance combined with more forgiving flight characteristics.[118] Such aircraft include the Titan T-51 Mustang, W.A.R. P-51 Mustang, Linn Mini Mustang, Jurca Gnatsum, Thunder Mustang, and Loehle 5151 Mustang.[119]

See also

- Related development

- Cavalier Mustang

- FK-Lightplanes SW51 Mustang production scale replica

- North American A-36

- Rolls-Royce Mustang Mk.X

- North American F-82 Twin Mustang

- North American FJ-1 Fury

- Piper PA-48 Enforcer

- Stewart S-51D Mustang Homebuilt scale replica

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Focke-Wulf Fw 190D

- Focke-Wulf Ta 152

- Hawker Tempest

- Lavochkin La-9

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Supermarine Spitfire

- Yakovlev Yak-9

- Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of aircraft of the United Kingdom in World War II

- List of fighter aircraft

- Allied technological cooperation during World War II

References

Notes

- ↑ While the Merlin powered Mustangs demonstrated much higher top speeds at altitudes above 15,000 ft than the Allison powered variants, it is a myth that the range of the Merlin-engined Mustang improved over that of the Allison variants; depending on conditions, both engines provided the Mustang with long range capabilities.[9]

- ↑ Among Allied aircraft, the P-51's victory total in World War II was second only to the carrier borne Grumman F6F Hellcat.[12]

- ↑ Because the new fighter was designed to a British, rather than an American or USAAC, specification it was allocated a private-venture civil designation instead of the more usual XP- (eXperimental Pursuit) group.

- ↑ For more specific information on the P-51's airfoil, known as the NAA/NACA 45–100 series, see[20]

- ↑ One of the NA-73s given to the army, s/n 41-038 is still in existence and last flew in 1982.[26]

- ↑ Adolf Galland thought the P-38 "clearly inferior" to the Luftwaffe's own fighters.[33]

- ↑ All but three of these FGs flew P-38s, P-40s or P-47s before converting to the Mustang.

- ↑ "Ziemi Czerwieńskiej" = "Land of Czerwien", RAF Polish units retained the name and the logo of a squadron from the Polish Air Force which fought the Germans in 1939.

- ↑ Note that all panel lines on the upper wings have been carefully filled, smoothed and primed before application of (on natural metal Mustangs) final coats of high speed silver lacquer. Even small flaws on the surface of P-51 wings could cut performance.

- ↑ The P-51D and K Maintenance manual notes that carrying 1,000 lb bombs was not recommended because the racks were not designed for them.[112] Three rockets could be carried on removable 'Zero Rail' launchers with the wing racks installed, 10 without wing racks.[113]

Citations

- ↑ "Mustang Aces of the Ninth & Fifteenth Air Forces & the RAF".

- ↑ Hickman. Kennedy. "World War II: North American P-51 Mustang". About.com. Retrieved: 19 June 2014

- 1 2 "North American P-51D Mustang." National Museum of the United States Air Force, 2 April 2011. Retrieved: 17 January 2012.

- 1 2 Knaack 1978

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp. 77, 90-2, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Borth 1945, pp. 92, 244.

- ↑ Kinzey 1996, p. 5.

- ↑ Kinzey 1996, p. 56.

- ↑ Kinzey 1996, p. 57.

- ↑ Kinzey 1997, pp. 10–13.

- 1 2 Gunston 1984, p. 58.

- ↑ Tillman 1996, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Wagner, Ray (2014-12-02). "chapter 3". Mustang Designer: Edgar Schmued and the P-51. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588344281.

- ↑ Pearcy 1996, p. 15.

- ↑ Pearcy 1996, p. 30.

- 1 2 Delve 1999, p. 11.

- ↑ Delve 1999, p. 12.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 3.

- ↑ Wagner 2000, pp. 16, 18.

- ↑ Selig, Michael. "P-51D wingroot section." uiuc.edu. Retrieved: 22 March 2008

- ↑ Yenne 1989, p. 49.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, p. 4.

- ↑ Kinzey 1996, pp. 5, 11.

- ↑ Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft, p. 6.

- ↑ "P-51 History: Mustang I." The Gathering of Mustangs & Legends. Retrieved: 26 March 2009.

- ↑ "North American XP-51 Prototype No. 4 – NX51NA ." EAA AirVenture Museum (Experimental Aircraft Association). Retrieved: 23 July 2013.

- 1 2 Miller 2007, p. 41.

- ↑ Miller 2007, p. 46.

- ↑ Miller 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ Hastings 1979, pp. 214–215.

- ↑ Craven and Cate 1949, pp. 704–705.

- ↑ Boylan 1955, p. 154.

- ↑ Galland1954, p. 148

- ↑ Boylan 1955, p. 155.

- ↑ Boylan 1955, pp. 155-156.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp. 77, 90-92, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Dean 1997, p. 338.

- ↑ Caldwell and Muller 2007, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ Ethell and Sand 2002, p. 126.

- ↑ Spick 1983, p. 111.

- ↑ Bowen 1980

- ↑ Sherman, Steven. "Aces of the Eighth Air Force in World War Two." Ace pilots, June 1999. Retrieved: 7 August 2011.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 77, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Olmsted 1994, p. 144.

- ↑ Forsyth 1996, pp. 149, 194.

- ↑ Scutts 1994, p. 58.

- ↑ Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Glancey 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Dean 1997, p. 339.

- ↑ "4th Fighter Wing." Global Security. Retrieved: 12 April 2007.

- ↑ Thompson with Smith 2008, p. 233.

- ↑ Flight Tests on the North American P-51B-5-NA Airplane, Army Air Forces Material Command, Flight Test Engineering Branch, Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, 24 April 1944

- ↑ Sims 1980, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ "Kurt Buhligen (deceased) - Art prints and originals signed by Kurt Buhligen (deceased)". directart.co.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "'Mustang' Taken Out of Mothballs For Demonstration". The Okaloosa News-Journal, Crestview, Florida, Volume 43, Number 14, page 3E.

- 1 2 Gunston, Bill. North American P-51 Mustang. New York: Gallery Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8317-1402-6.

- ↑ Wixey 2001, p. 55.

- ↑ "Dominican Republic." acig.org. Retrieved: 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Munson 1969, p. 97.

- ↑ Anderson 1975, pp. 16–43.

- ↑ Anderson 1975, pp. 50–65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Gunston 1990 p. 39.

- ↑ Hagedorn 1993, p. 147.

- ↑ Hagedorn 2006

- ↑ Dienst 1985

- ↑ Gunston and Dorr 1995, p. 107.

- ↑ Gunston and Dorr 1995, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2004, pp. 78–79, 80, 82.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2004, pp. 108–114.

- ↑ Gilman and Clive 1978, p. 314.

- ↑ Gunston and Dorr 1995, p. 108.

- ↑ Cavalier Mustangs Mustangs-Mustangs. Retrieved: 12 April 2007.

- ↑ "Indonesian Air Arms Overview". Scramble: Dutch Aviation Society. Retrieved: 12 April 2007.

- ↑ Darling 2002, p. 66.

- ↑ Yenne 1989, p. 62.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2003

- ↑ Kahin 2003, p. 90.

- 1 2 Wilson 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ "Blue Diamonds: Philippine Air Force." geocities.com. Retrieved: 21 March 2008.

- ↑ "309 Sqn photo gallery." polishairforce.pl. Retrieved: 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Mietelski 1981

- ↑ "Somali (SOM)." World Air Forces. Retrieved: 10 September 2011.

- ↑ Andersson, Lennart and Leif Hellström. Bortom Horisonten: Svensk Flygspaning mot Sovjetunionen 1946–1952 (in Swedish). Stockholm: All about Hobbies, 2009. ISBN 978-91-7243-015-0.

- ↑ Gruenhagen 1980, p. 193.

- ↑ Gruenhagen 1980, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Delve (1994) p 191

- ↑ Gruenhagen 1980, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Gruenhagen 1980, pp. 201, 205.

- ↑ Gordon 2008, pp. 448–449.

- ↑ Kyburz, Martin. "Racing Mustangs." Swiss Mustangs, 2009. Retrieved: 17 January 2012.

- ↑ "Mustang NA P-51C Mustang." NASM. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- 1 2 "P-51s for Sale." mustangsmustangs.net. Retrieved: 30 September 2010.

- ↑ "North American P-51". FAA Registry. Retrieved: 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Aircraft rides." Dixie Wing. Retrieved: 1 September 2010. Archived 4 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Doug Matthews sets several records flying a P-51 Mustang". World Warbird News. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Doug Matthews Sets World Records in P-51D". eaa.org. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "July 2012 NAA Record Newsletter". constantcontact.com. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ http://www3.ntsb.gov/aviationquery/brief.aspx?ev_id=86405&key=0 NTSB Report on Penn's fatal mishap Archived 20 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The Crash at Farrell's Ice Cream Parlor in Sacramento, CA – September 24, 1972, Postcript." Check Six, 2002. Retrieved: 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Barboza, Tony. "Reno air races crash: NTSB investigates elevator trim tab." Los Angeles Times, June 14, 2012. Retrieved: September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Pope, Stephen. "Two Killed in Crash of P-51 Galveston Gal". Flying magazine, 29 October 2013.

- ↑ "WWII plane crash: P-51 flight was anniversary gift." The Christian Science Monitor, 24 October 2013.

- ↑ "Two killed in plane crash at airport". The Durango Herald. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Andrade, John M. U.S. Military Aircraft Designations and Serials since 1909, p. 150. Leicester, UK: Midland Counties Publication, 1979, ISBN 0-904597-22-9.

- ↑ "History of the TP-51C Mustang." Collings Foundation. Retrieved: 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Birch 1987, pp. 96–98.

- ↑ AN 01-60JE-2 1944.

- ↑ P-51 Tactical Planning Characteristics & Performance Chart

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 2001

- ↑ Loftin 2006.

- ↑ "Objects: A19520106000 – Packard (Rolls-Royce) Merlin V-1650-7." Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Collections Database.

- ↑ AN 01-60JE-2 1944, pp. 398–399.

- ↑ AN 01-60JE-2 1944, p. 400.

- ↑ Pilot's Flight Operating Instructions, Army Model P-51-D-5, British Model Mustang IV Airplanes (April 5, 1944), pp. 38-40. Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ↑ Johnson 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ "Red Tails Promotional trailer." Youtube.com. Retrieved: 18 January 2012.

- ↑ Smith, O.S. "Other Mustang Kits and Links." Unofficial Stewart 51 Builders Page. Retrieved: 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "Where Dreams Take Flight." Titan Aircraft, 2012. Retrieved: 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "P-51D Mustang Replica." SOS-Eisberg, 2012. Retrieved: 24 April 2012.

Bibliography

- Aerei da combattimento della Seconda Guerra Mondiale (in Italian). Novara, Italy: De Agostini Editore, 2005.

- Anderson, Peter N. Mustangs of the RAAF and RNZAF. Sydney, Australia: A.H. & A.W. Reed Pty Ltd, 1975. ISBN 0-589-07130-0.

- Angelucci, Enzo and Peter Bowers. The American Fighter: The Definitive Guide to American Fighter Aircraft from 1917 to the Present. New York: Orion Books, 1985. ISBN 0-517-56588-9.

- Birch, David. Rolls-Royce and the Mustang. Derby, UK: Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-9511710-0-3.

- Bowen, Ezra. Knights of the Air (Epic of Flight). New York: Time-Life Books, 1980. ISBN 0-8094-3252-8.

- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1945.

- Bowman, Martin W. P-51 Mustang vs Fw 190: Europe 1943–45. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1-84603-189-3.

- Boylan, Bernard. Development of the Long Range Escort Fighter. Washington, D.C: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1955. Retrieved: 15 July 2014.

- Boyne, Walter J. Clash of Wings. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994. ISBN 0-684-83915-6.

- Breffort, Dominique with André Jouineau. Le North-American P-51 Mustang – de 1940 à 1980 (Avions et Pilotes 5)(in French). Paris: Histoire et Collections, 2003. ISBN 2-913903-80-0.

- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. "The North American Mustang." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Caldwell, Donald and Richard Muller. The Luftwaffe over Germany – Defense of the Reich. St. Paul, Minnesota: Greenhill books, MBI Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-185367-712-0.

- Carson, Leonard "Kit." Pursue & Destroy. Granada Hills, California: Sentry Books Inc., 1978. ISBN 0-913194-05-0.

- Carter, Dustin W. and Birch J. Matthews.Mustang: The Racing Thoroughbred. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Company, 1992. ISBN 978-0-88740-391-0.

- Craven, Wesley and James Cate. The Army Air Forces in World War II, Volume Two: Europe, Torch to Pointblank, August 1942 to December 1943. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1949.

- Darling, Kev. P-51 Mustang (Combat Legend). Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife, 2002. ISBN 1-84037-357-1.

- Davis, Larry. P-51 Mustang. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-89747-350-7.

- Dean, Francis H. America's Hundred Thousand. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1997. ISBN 0-7643-0072-5.

- Delve, Ken. The Mustang Story. London: Cassell & Co., 1999. ISBN 1-85409-259-6.

- Delve, Ken. The Source Book of the RAF. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1-85310-451-5.

- Dienst, John and Dan Hagedorn. North American F-51 Mustangs in Latin American Air Force Service. London: Aerofax, 1985. ISBN 0-942548-33-7.

- Donald, David, ed. Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Etobicoke, Ontario: Prospero, 1997. ISBN 1-85605-375-X.

- Dorr, Robert F.. P-51 Mustang (Warbird History). St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-7603-0002-X.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. Mustang: A Documentary History of the P-51. London: Jane's Publishing, 1981. ISBN 0-531-03736-3

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. P-51 Mustang: In Color, Photos from World War II and Korea. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers, 1993. ISBN 0-87938-818-8.

- Ethell, Jeffrey and Robert Sand. World War II Fighters. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 2002. ISBN 978-0-7603-1354-1.

- Forsyth, Robert. JV44: The Galland Circus. Burgess Hill, West Sussex, UK: Classic Publications, 1996. ISBN 0-9526867-0-8

- Furse, Anthony. Wilfrid Freeman: The Genius Behind Allied Survival and Air Supremacy, 1939 to 1945. Staplehurst, UK: Spellmount, 1999. ISBN 1-86227-079-1.

- Gilman J.D. and J. Clive. KG 200. London: Pan Books Ltd., 1978. ISBN 0-85177-819-4.

- Glancey, Jonathan. Spitfire: The Illustrated Biography. London: Atlantic Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84354-528-6.

- Gordon, Yefim. Soviet Air Power in World War 2. Hinckley, UK: Midland Ian Allan Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-85780-304-4.

- Grant, William Newby. P-51 Mustang. London: Bison Books, 1980. ISBN 0-89009-320-2.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Gruenhagen, Robert W. Mustang: The Story of the P-51 Fighter (rev. ed.). New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1980. ISBN 0-668-04884-0.

- Gunston, Bill. An Illustrated Guide to Allied Fighters of World War II. London: Salamander Books Ltd, 1981. ISBN 0-668-05228-7.

- Gunston, Bill. Aerei della seconda guerra mondiale (in Italian). Milan: Peruzzo editore, 1984. No ISBN.

- Gunston, Bill. North American P-51 Mustang. New York: Gallery Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8317-1402-6.

- Gunston, Bill and Robert F. Dorr. "North American P-51 Mustang: The Fighter That Won the War." Wings of fame, Volume 1. London: Aerospace, 1995, pp. 56–115. ISBN 1-874023-74-3.

- Hagedorn, Dan. Central American and Caribbean Air Forces. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians), 1993. ISBN 0-85130-210-6.

- Hagedorn, Dan. Latin American Air Wars & Aircraft. Crowborough, UK: Hikoki, 2006. ISBN 1-902109-44-9.

- Hastings, Max. Bomber Command. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0-76034-520-7.

- Hess, William N. Fighting Mustang: The Chronicle of the P-51. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970. ISBN 0-912173-04-1.

- "History, Boeing: P-51 Mustang". Boeing. Retrieved: 24 June 2014.

- Jackson, Robert. Aircraft of World War II: Development, Weaponry, Specifications. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, 2003. ISBN 0-7858-1696-8.

- Jackson, Robert. Mustang: The Operational Record. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1992. ISBN 1-85310-212-1.

- Jerram, Michael F. P-51 Mustang. Yeovil, UK: Winchmore Publishing Services Ltd., 1984, ISBN 0-85429-423-6.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. Bell P-39/P-63 Airacobra & Kingcobra. St. Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 1998. ISBN 1-58007-010-8.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. North American P-51 Mustang. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, 1996. ISBN 0-933424-68-X.

- Kaplan, Philip. Fly Navy: Naval Aviators and Carrier Aviation: A History. New York: Michael Friedman Publishing Group Incorporated, 2001. ISBN 1-58663-189-6.

- Kinzey, Bert. P-51 Mustang in Detail & Scale: Part 1; Prototype through P-51C. Carrollton, Texas: Detail & Scale Inc., 1996. ISBN 1-888974-02-8.

- Kinzey, Bert. P-51 Mustang in Detail & Scale: Part 2; P-51D thu P-82H. Carrollton, Texas: Detail & Scale Inc., 1997. ISBN 1-888974-03-6

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume 1 Post-World War II Fighters 1945–1973. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5.

- Lednicer, David A. and Ian J. Gilchrist. "A Retrospective: Computational Aerodynamic Analysis Methods Applied to the P-51 Mustang." AIAA paper 91-3288, September 1991.

- Lednicer, David A. "Technical Note: A CFD Evaluation of Three Prominent World War II Fighter Aircraft." Aeronautical Journal, Royal Aeronautical Society, June/July 1995.

- Lednicer, David A. "World War II Fighter Aerodynamics." EAA Sport Aviation, January 1999.

- Leffingwell, Randy (and David Newhardt, photography). Mustang: 40 Years. St. Paul, Minnesota: Crestline (Imprint of MBI Publishing Company), 2003. ISBN 0-7603-2122-1.

- Liming, R.A. Mathematics for Computer Graphics. Fallbrook, California: Aero Publishers, 1979. ISBN 978-0-8168-6751-6.

- Liming, R.A. Practical Analytic Geometry With Applications to Aircraft. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1944.

- Loftin, LK, Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft, NASA SP-468. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Office. Retrieved: 22 April 2006.

- Lowe, Malcolm V. North American P-51 Mustang (Crowood Aviation Series). Ramsbury, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-86126-830-3.

- Loving, George. Woodbine Red Leader: A P-51 Mustang Ace in the Mediterranean Theater. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003. ISBN 0-89141-813-X.

- Matricardi, Paolo. Aerei militari: Caccia e Ricognitori(in Italian). Milan: Mondadori Electa, 2006.

- Mietelski, Michał, Samolot myśliwski Mustang Mk. I-III wyd. I (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1981. ISBN 83-11-06604-3.

- Miller, Donald L. Eighth Air Force: The American Bomber Crews in Britain. London: Aurum Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-84513-221-7.

- Munson, Kenneth. Caccia e aerei da attacco e addestramento dal 1946 ad oggi(in Italian). Torino: Editrice S.A.I.E., 1969. No ISBN.

- O'Leary, Michael. P-51 Mustang: The Story of Manufacturing North American's Legendary World War II Fighter in Original Photos. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-58007-152-9.

- O'Leary, Michael. USAAF Fighters of World War Two. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 1986. ISBN 0-7137-1839-0.

- Olmsted, Merle. The 357th Over Europe: the 357th Fighter Group in World War II. St. Paul, Minnesota: Phalanx Publishing, 1994. ISBN 0-933424-73-6.

- Pace, Steve. "Mustang - Thoroughbred Stallion of the Air". Stroud, UK: Fonthill Media, 2012. ISBN 978-1-78155-051-9

- Pearcy, Arthur. Lend-Lease Aircraft in World War II. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1996. ISBN 1-85310-443-4.

- Sgarlato, Nico. "Mustang P-51" (in Italian). I Grandi Aerei Storici (Monograph series) N.7, November 2003. Parma, Italy: Delta Editrice. ISSN 1720-0636.