Póvoa de Varzim

| Póvoa de Varzim | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

|

Clockwise from top: Nova Póvoa, Rua Santos Minho, Touro, the City Park, Lagoa Beach, Senhora das Dores Church, and Praça do Almada. | |||

| |||

|

Motto: Ala-arriba! (Portuguese) "Go upwards!" | |||

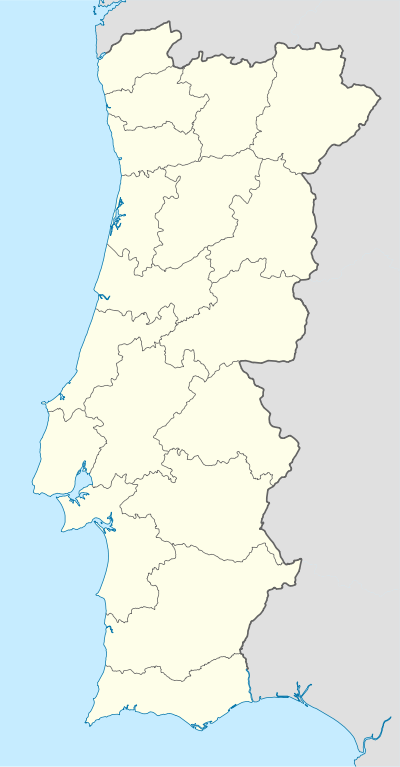

Póvoa de Varzim Location in Portugal | |||

| Coordinates: 41°22′48″N 8°45′39″W / 41.38000°N 8.76083°WCoordinates: 41°22′48″N 8°45′39″W / 41.38000°N 8.76083°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | Norte | ||

| Subregion | Grande Porto | ||

| District | Porto | ||

| Roman control | ca. 138 BC | ||

| Fiefdom | 1033 | ||

| Municipal charter | March 9, 1308 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | City council and Assembly | ||

| • Mayor | Aires Pereira (PSD) | ||

| • Assembly president | Afonso Pinhão Ferreira (PSD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 82.1 km2 (31.7 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 190 m (620 ft) | ||

| Highest elevation | 202 m (663 ft) | ||

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) | ||

| Population (2011) | |||

| • Total | 63,408 | ||

| • Density | 770/km2 (2,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Poveiro, Poveira (Povoan) | ||

| Time zone | WET (UTC0) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | WEST (UTC) | ||

| Postal code | 4490-000 — 4490-999, 4494-909, 4495-001 — 4495-613, 4496-903, 4750-010 — 4750-554 | ||

| Area code(s) | 252 | ||

| Municipal Holiday | June 29, St. Peter Festival | ||

| Website | www.cm-pvarzim.pt | ||

Póvoa de Varzim (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpɔvwɐ ðɨ vɐɾˈzĩ], locally [ˈpɔβwə ðɨ βəɾˈzĩŋ]), also spelled Povoa de Varzim, is a Portuguese city in Northern Portugal and sub-region of Greater Porto. It sits in a sandy coastal plain, a cuspate foreland, halfway between the Minho and Douro rivers. The population of the municipality was 63,408 at the time of the 2011 census. According to the 2001 census, there were 63,470 inhabitants, with 42,396 living in the city proper.[1] The city expanded, southwards, to Vila do Conde, and there are about 100,000 inhabitants in the urban area alone. It is the seventh-largest urban agglomeration in Portugal and the third largest in Northern Portugal.

Permanent settlement in Póvoa de Varzim dates back to around four to six thousand years ago; around 900 BC, unrest in the region led to the establishment of Cividade de Terroso, a fortified city, which developed maritime trade routes with the civilizations of classical antiquity. Modern Póvoa de Varzim emerged after the conquest by the Roman Republic of the city by 138 BC, fishing and fish processing units soon developed, which turned out to be the foundations of the local economy. By the 11th century, the fish industry and fertile farmlands were the economic base of a feudal lordship and Varzim was fiercely disputed between the local overlords and the early Portuguese kings, which resulted in the establishment of the present day's municipality in 1308 and being subdued to monastic power some years later. Póvoa de Varzim's importance reemerged with the Age of Discovery due to its shipbuilders and merchants proficiency and wealth, who traded around the globe in complex trade routes. By the 17th century, the fish processing industry rebounded and, some time later, Póvoa became the dominant fishing port in northern Portugal.[2]

Póvoa de Varzim has been a well-known beach resort for over three centuries, the most popular in Northern Portugal,[3] which unfolded an influential literary culture and artistic patronage in music and theater. Póvoa de Varzim is one of the few legal gambling areas in Portugal, and has significant textile and food industries.[3] The town has retained a distinct cultural identity and ancient customs such as the writing system of siglas poveiras, the masseira farming technique and festivals.

History

Castro Culture and Roman conquest

Discoveries of Acheulean stone tools suggest Póvoa de Varzim has been inhabited since the Lower Palaeolithic, around 200,000 BC. The first groups of shepherds settled on the coast where Póvoa de Varzim is now located between the 4th millennium and early 2nd millennium BC.[4] A Neolithic-Calcolithic necropolis, with seven known burial mounds, can still be seen around São Félix Hill and Cividade Hill.[5]

Widespread pillaging by rival tribes led the resident populations of the coastal plain of Póvoa de Varzim to raise a fortified town atop the hill that stood next to the sea.[6] The city area covered 12,000 m2 (3.0 acres) and had several hundred inhabitants. It maintained commercial relations with the Mediterranean civilizations, during the Carthaginian dominion of the southern Iberian Peninsula.[4]

During the Punic Wars, the Romans became aware of the Castro region's rich deposits of gold and tin. Viriathus, leading Lusitanian troops, hindered the expansion of the Roman Republic north of the river Douro. His murder in 138 BC opened the way for the Roman legions. Over the following two years, Decimus Junius Brutus advanced into the Castro region from south of the Douro, crushed the Castro armies, and left Cividade de Terroso, in ruins.[4]

The region was pacified during the reign of Caesar Augustus and the Castro people returned to the coastal plain, where Villa Euracini and Roman fish factories were built.[7][8] With the annexation by the Roman Republic, trading supported regional economic development, with Roman merchants organized in true commercial companies who looked for monopoly in commercial relations.[9]

Feudalism and municipalism

With the fall of the Roman Empire, Suebi populations established themselves in the countryside.[10] It was first mentioned on March 26, 953 during the rule of Mumadona Dias, Countess of Portugal.[11] The region was attacked by the Vikings in the 960s, by the Moors in 997 and again by Norman pirates in 1015-1016.[10][12] Hints indicate a Norse settlement in Villa Euracini after those invasions.[13] During the Middle Ages, the name Euracini evolved to Uracini, Vracini, Veracini, Verazini, Verazim, Varazim and, eventually, Varzim.[7]

In 1033, Guterre Pelayo, a leading captain of the Reconquista for the County of Portugal, was recognized by Bermudo, Emperor in Gallaecia, as the Lord of Varzim, during the cahotic epoch following Almanzor's attack on the Christian realms. Henry, the Portuguese count, recognized his rule over the port of Varzim amongst several other possessions.[14] Varzim overlords gained significant power and, when Portugal was already a stable kingdom, Sancho I of Portugal attacked the fief and seized the port, destroyed most of the properties and expelled the farmers. The northern area became known as Varzim dos Cavaleiros (Knights' Varzim) and belonged to the military order of the Knights Hospitaller, who inherited the wealth of the local overlords. Lower Varzim, the royal southern land, was the location of the port and contiguous farmlands.[15][16]

According to a 1258 chronic, while Sancho II of Portugal was disputing the throne with his brother, Afonso, who was invited by the knights to take over the Portuguese throne, Gavião of Varzim used the opportunity to destroy the king's assets in Lower Varzim. He violently entered in the king's lands, destroyed it significantly, in such a way that no bread could be sowed, nor a car could cross that place as it often used to do. Sancho II was overthrown, Afonso became king and ordered the resettlement of the royal land and king's chronicler explicitly stated that all the port was property of the king.[17]

Gomes Lourenço, of the Honour of Varzim, was a very influential knight and godfather of King Denis.[16] He took advantage of his relationship with important people in the kingdom in order to get the recognition of the seaport, located in Lower Varzim, as his honour. He tried to convince King Denis, that the king's father, Afonso, took it from him unfairly. Justifying the attitude with the Honour of Varzim, Gomes and his descendants went to the port to get the tribute from the fishermen.[16]

In 1308, King Denis granted a charter, the Foral, giving the royal land to 54 families of Varzim; these had to found a municipality known as Póvoa around Praça Velha, siding Varzim Old Town, controlled by the knights. In 1312, King Denis donated Póvoa to his bastard son, Afonso Sanches, Lord of Albuquerque, who included it in the patrimony of the Monastery of Santa Clara, which he had just founded in Vila do Conde.[18] In 1367, King Ferdinand I confirmed the charters, privileges and uses of Póvoa de Varzim. These were again confirmed by John I in 1387. But the domain of the monastery over the town grew stronger and the people asked King Manuel I to end the situation. In 1514, during the era of charter reform, the King granted a new charter to Póvoa de Varzim. Besides the town hall and square, the town gained a pillory, granted significant self-government, and involved itself in the Portuguese discoveries.[11]

Shipbuilders, seafarers and fishermen

In the 16th century, the fishermen started to work in maritime activities, as pilots or seafarers in the crew of the Portuguese ships, due to their high nautical knowledge.[19] The fishermen of the region are known to fish in Newfoundland since, at least, 1506.[19] During the reign of John III the Povoan shipmaking art was already renowned, and Povoan carpenters were sought after by Lisbon's Ribeira das Naus shipyard due to their high technical skills.[20] The single floored houses dominated the town's landscape, but there are indications of multiple floored habitations with rich architecture. The seafarers' social class, well-off gentlemen, was associated with this richer architecture around Praça Velha square.[8]

In the 17th century, the shipbuilding industry boomed in Ribeira, area around Póvoa Fortress in the sheltered bay, and one third of the population had some relation with this activity, building ships for the merchant navigation. During this period there was a relevant urban expansion: the Praça civic center with the town hall and the Madre Deus Chapel, the area of the old town where the Main church was located and the fishermen neighborhood of Junqueira was starting its affirmation as a new urban center.[8]

In the beginning of the 18th century, there was a decline in the Ribeira shipyard activities, due to the aggradation of the Portuguese coast and the Povoan shipyard started to work in the construction of fishing vessels.[19] There was a significant increase of the fisher community in the middle of the century, becoming the main activity, and during the reign of Joseph I with the country in the middle of an economic crisis, Póvoa started a rapid development.[19] The Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon noticed their overwhelming notoriety in the Minho coast and considered Povoans to be the most expert fishermen from Cape St. Vincent to Caminha, with a sizable number of fishermen, ships and high sea fishing. The result was a very considerable quantity of caught fish.[21]

The community became wealthier and, following a royal provision by Queen Mary I in 1791, the inspector general Almada reorganized the town's layout, a new civic center with a monumental city hall, streets and infrastructure were built, all of which provided potential for a new business — sea baths.[11]

The Baths of Póvoa and the modern city

Since 1725, the iodine-rich seawaters of Póvoa, due to the peculiar high quantities of seaweed that ends up in Póvoa beaches from the sheltered bay to Cape Santo André, brought by ocean currents, lead that Benedictine monks choose to take sea-baths in there, searching cures for skin and bone problems. Still in the 18th century, other people went to Póvoa with the same concerns.[22] In the 19th century, the town became popular as a summer destination for the wealthy of Entre-Douro-e-Minho province and Portuguese Brazilians, due to its large sandy beaches and the development of theaters, hotels and casinos. It then became renowned for its refined literary culture, artistic patronage in music and theater, and intellectual tertulia.[20][23]

On February 27, 1892, a shipwreck had critical impact in community. Seven lanchas poveiras wrecked in a storm and 105 fishermen were killed, just metres off the shore.[24] Over-fishing by steamboats created severe social problems and fishermen emigration. The fishing industry lost much of its importance. Meanwhile, Póvoa developed into the most popular holiday destination in northern Portugal,[3] The textile and food industries thrived. Streetcars appeared in 1874 and endured until the first years of the 20th century. The rail connection to Porto opened in 1875 and to inland Minho region in 1878. National highways linking the city to Barcelos, Famalicão and Viana do Castelo opened. The first urbanization project for the waterfront was drafted in 1891. All these events led to a major growth between the 1930s and 1960s.[25]

Póvoa de Varzim developed a cosmopolitan style and became a service-sector city. It is one of northern Portugal's main urban centres. Póvoa is the focal point of a larger area, which includes Vila do Conde and Esposende.[23]

Geography

.jpg)

Occupying an area of 82.1 km2 (31.7 sq mi), Póvoa de Varzim lies between the Cávado and Ave rivers, or, from a wider perspective, halfway between the Minho and Douro rivers on the northern coast of Portugal — the Costa Verde. It is bordered to the north by the municipality of Esposende, to the northeast by Barcelos, to the east by Vila Nova de Famalicão, and to the south by Vila do Conde. To the west, it has a shoreline on the Atlantic Ocean.[26]

The rocky cliffs, common features downstream of the Minho's estuary, disappear in Póvoa de Varzim, giving way to a coastal plain. The plain is located in a cuspate foreland, an old marine plateau, conferring a sandy soil to the coastal lands, and forming sand dunes, currently preserved only in northern Aguçadoura. Wandering along the coast one discerns Cape Santo André, the tip of the cuspate foreland and the Avarus Promontory, referred to by Ptolemy.[27]

São Félix Hill (202 m or 663 ft) and Cividade Hill (155 m or 509 ft) rise above the landscape. Despite their modest rise, the expanse of the plain makes them easy reference points on the horizon. The mountain chain known as Serra de Rates divides the municipality in two distinctive areas: the coastal plain and hills where the forests become more abundant and the soils have less sea influence. In this landscape dominated by the plain and low hills, only the hill of Corga da Soalheira (150 m or 490 ft) in the interior, is easily recognizable.[27]

The municipality has no large rivers, but abundant small water streams exist. Some of these courses are permanent, such as the Este River, which feeds into the Ave. The source of the Esteiro Stream is located at the base of Cividade Hill and empties at the beach of Aver-o-Mar, while the Alto River's source is at the base of São Félix and reaches the Atlantic at Rio Alto Beach. The land is well-irrigated, springs and wells are very common, since underground water is often close to the surface.[4]

The forest areas suffer from strong demographic pressure and intensive agriculture. Forests are still important in parishes surrounded by the Serra de Rates, whose flora is distinguished by the pedunculate oak or the european holly. In the 18th century, the monks of Tibães planted pines, which characterized the civil parish of Estela. In the past the Atlantic forest predominated, with trees such as oaks, ash trees, hazels, strawberry trees, holm oak, and alders.[4] The rocks throughout the entire coastline are home to large populations of clams, fish and seaweed. These rocks and the dunes form rich ecosystems, but are threatened by holiday-makers, dune sports and waterfront construction.[28]

Climate

Póvoa's climate is classified as Mediterranean climate (Csb in the Köppen climate classification system), with gentle summers and mild winters, influenced by the Atlantic ocean.[29] Average temperatures oscillate between 12.5 and 15 °C (54.5 and 59.0 °F). Temperature extremes recorded at Sá Carneiro Airport, records started in 1967, range from −3.8 °C (25.2 °F) to 38.3 °C (100.9 °F). Between 1971 and 2000, on average there were 4.2 days a year below 0 °C (32.0 °F) and 10.1 days a year above 30 °C (86.0 °F). The city possesses a microclimate and is considered the region least subject to frosts in all northern Portugal, and very uncommon snowfall, due to the winter winds that normally blow from the south and southwest.[4]

Most of the rain is concentrated in the winter months, due to the Azores High which influences the subsidence of the air resulting in very dry air during the summer. Topography and distance from the sea influences precipitation even at short distances.[30] The urban area receives between 900 millimetres (35 in) and 1,200 millimetres (47 in) of rain per year, while the city's countryside can get up to 1,500 millimetres (59 in).[31] The prevailing northern winds, known as Nortadas, arise in the summer after midday.[4] During its dry summer, a mass of hot and wet air, brought by the south and western maritime winds, creates the city's characteristic fog covering only the coast, which often dissipates with the afternoon sun.[32]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1720 | 1,396 | — |

| 1736 | 1,796 | +28.7% |

| 1750 | 2,184 | +21.6% |

| 1768 | 3,360 | +53.8% |

| 1780 | 3,776 | +12.4% |

| 1795 | 4,328 | +14.6% |

| 1801 | 4,676 | +8.0% |

| 1821 | 5,672 | +21.3% |

| 1830 | 6,097 | +7.5% |

| 1836 | 8,036 | +31.8% |

| 1849 | 15,300 | +90.4% |

| 1864 | 18,704 | +22.2% |

| 1878 | 20,578 | +10.0% |

| 1890 | 23,372 | +13.6% |

| 1900 | 24,527 | +4.9% |

| 1911 | 25,083 | +2.3% |

| 1920 | 25,929 | +3.4% |

| 1930 | 28,780 | +11.0% |

| 1940 | 31,693 | +10.1% |

| 1950 | 37,938 | +19.7% |

| 1960 | 40,444 | +6.6% |

| 1970 | 42,698 | +5.6% |

| 1981 | 54,248 | +27.1% |

| 1991 | 54,788 | +1.0% |

| 2001 | 63,470 | +15.8% |

| 2011 | 63,408 | −0.1% |

| Before 1849, data refers only to Póvoa de Varzim Parish (N.S. Conceição). 1720-1836 Sources:[8] 1864-2001,[33] | ||

A native of Póvoa de Varzim is called a Poveiro which can be rendered into English as Povoan. According to the 2001 Census, there were 63,470 inhabitants that year, 38 848 (61.2%) of whom lived in the city. The number goes up to 100,000 if adjacent satellite areas are taken into account,[23] ranking it as the seventh largest independent urban area in Portugal, within a polycentric agglomeration of about 3 million people, ranging from Braga to Porto.[34]

The urban area has a population density of 3035/km2 (7,864/mi²), while the rural and suburban areas have a density of 355.5/km2 (920/mi²). The rural areas away from the city tend to be scarcely populated, becoming denser near it. During the summer the resident population in the city triples; this seasonal movement from neighbouring cities is due to the draw of the beach and 29.9% of homes had seasonal use in 2001, the highest in Greater Porto.[35] Póvoa de Varzim is the youngest city in the region with a birth rate of 13.665 and mortality rate of 8.330.[36] Unlike other urban areas of greater Porto, it is not a satellite city. Significant commuting occurs only with Vila do Conde,[35] an urban expansion area of Póvoa since the 18th century.[37]

For centuries a fishing community of mostly Norman origin, where ethnic isolationism was a common practice, Póvoa de Varzim is today a cosmopolitan town, with people originating from the Ave Valley who settled in the coastal Northern districts during the 20th century, the ancient immigration from Galicia,[38] Portuguese-Africans (who arrived in significant numbers after the independence of Angola and Mozambique) in the late 1970s and people of diverse nationalities, the biggest immigrant communities are Ukrainians, Brazilians, Chinese, Russians, and Angolans.[39]

The population of the entire municipality grew only 1% between 1981 and 1991, then increased by 15.3% between 1991 and 2001. During that period, the urban population had grown 23%, with the number of families increasing considerably — by about 44.5%. In 2005 Expresso considered it as the most developed in Porto district and Primeiro de Janeiro as the "city of future" in the Porto district, the quality of living, the infrastructure development such as the light rail metro and a 15 minutes distance from Porto and Braga, prompted new residents originating from near-by cities such as Guimarães, Famalicão, Braga and Porto which lead to a real estate development that may double the resident population in the medium term.[40]

Due to the practice of endogamy and the caste system, Póvoa's fishing community maintained local ethnic characteristics. Anthropological and cultural data indicate Nordic fishermen settling during the period of the coast's resettlement.[13] In As Praias de Portugal (Beaches of Portugal, 1876), Ramalho ortigão wrote that the Povoan fishermen were a "race" in the Portuguese coast; entirely different from the Mediterranean type of Ovar and Olhão, Poveiro is of "Saxon" type. On the other hand, the man from the interior was a farmer with Galician character (Paleo and Nordid-Atlantid). In a 1908 research, anthropologist Fonseca Cardoso considered that Poveiros were the result of a mixture of Phoenicians, Teutons, Jews and, mostly, Normans.[41] In the book The Races of Europe (1938), Poveiros were distinguished by having a greater than usual degree of blondism, broad faces of unknown origin, and broad jaws.[42]

Poveiros have migrated to other places and this attenuated the population growth. One should notice that the Poveiros tended to create their own associations abroad, there are Casa dos Poveiros (Poveiros House) in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo), Germiston in South Africa and Toronto in Canada. In Rio de Janeiro, the community was known by not wanting other peoples of other origins, including Portuguese born in other regions, within their community. In 1920, many Poveiros emigrated in Brazil returned, as many refused to lose Portuguese nationality.[43] The governor of Angola, with an ambition to develop fisheries, suggested the creation of a Povoan colony in Porto Alexandre. Due to fisher classes affairs, the fisher areas of Vila do Conde, Esposende and Matosinhos have strong Povoan cultural influence and half of the population of Vila do Conde and Matosinhos are of Povoan descent.[44]

Economy

The economy of Póvoa de Varzim is driven by tourism (namely gambling, hotels and restaurants), manufacturing, construction, fishing, and agro-business. During the 2001 census, 1770 companies are headquartered in Póvoa de Varzim, of which 2.82% were of the primary sector, 33.73% of the secondary and 63.45% of the tertiary. Despite its weight in Greater Porto international trade is weak, in 2004 it represented 1.1% of departures and 0.9% of arrivals, its coverage rate of arrivals against departures suppressed the 100% mark.[36] The activity rate had grown from 48% to 51.1% from 1991 to 2001,[23] but there were 3353 citizens unemployed in June 2006.[45]

Póvoa de Varzim has been noted internationally for its Renewable energy industry. The world's first commercial wave farm was located in its coast,[46] at the Aguçadora Wave Park. The wave farm used Pelamis P-750 machines.[47][48][49] The project failed and was replaced by the windfloat project, a new proctotype on offshore wind farms, from a distinct company, that is still operating.[50] Energie, a company headquartered in Póvoa de Varzim, developed a thermodynamic solar system combining solar energy and a heat pump to generate energy.[51]

The fact that it is a seaside city has shaped Póvoa de Varzim's economy: the fishing industry, from the fishing vessels that put in each day to the canning industry and to the city's fish market, beach agriculture, seaweed-gathering for fertilizing fields, and tourism are the result of its geography. Tourism and the related industries are more relevant in Póvoa's economy these days, as fisheries have lost importance. Nevertheless, the mean value of fish landed in 2004, in its seaport, was almost three times that of Matosinhos seaport and significantly higher in the average vessels' capacity. Its fishing productivity is also comparatively higher than the national average.[36] A Poveira is a traditional Povoan canning factory and most of its production, 80 to 85%, is exported and deals with high-end brands in canned fish, for MDC markets such as Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Scandinavia, Austria, Singapore and Australia.[52][53] Export market brands include: Poveira, D'Henry IV, Ala-Arriba, Minerva, and Alva.[54]

Monte Adriano, the seventh largest construction company in Portugal,[55] and the joint venture between the Royal Lankhorst Euronete and Quintas & Quintas, producer of deepwater mooring systems, are two large companies based in the city.[56] The manufacturing industry is an important employer, mostly in the textile industry that has low productivity and income. These industries are located out of the city in Beiriz, Balasar, and Rates. Other employers include the blanket handicraft industry of Terroso and Laundos, and the wood industries of Rates. One of the initiatives of the municipality is the Parque Industrial de Laundos (Industrial Park of Laundos), in the city's outskirts, next to the A28 Motorway.[57]

In the coast, the masseira farm fields were developed. This technique increases agricultural yields by using large, rectangular depressions dug into sand dunes, with the spoil piled up into banks surrounding the depression. Grapes are cultivated on the banks to the south, east and west, and trees and reeds on the northern slope act as a windbreak against the prevailing northern wind. Garden crops are grown in the central depression.[58] Póvoa de Varzim is part of the ancient Vinho Verde winemaking region. Production is still specialized in horticultural goods, but most of the masseiras were substituted by greenhouses and a significant share of the production is exported to other Western European markets. The inland valley region is committed to milk production and the Agros corporation headquarters of Lactogal, the largest dairy products and milk producer company in the Iberian Peninsula, is located in Espaço Agros and has several departments such as exhibition park and laboratories, and the largest agricultural project in northern Portugal.[59]

Government

The City Council and assembly are lodged in a 1790 Neoclassical style building. | |

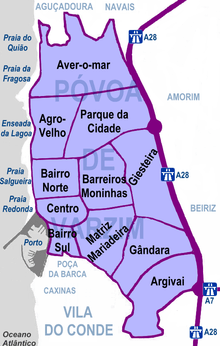

| Civil parishes of Póvoa de Varzim | |

Póvoa de Varzim is governed by a Câmara Municipal (City Council) composed of nine councilmen. A Municipal Assembly exists and it is the legislative body of the municipality.

After the first free elections, with the end of the Estado Novo period, only right-wing parties have governed the city: the city council was governed by the CDS between 1976 and 1989 and since then by the PSD. The CDS saw its popularity suffer an abrupt decline in 1997, and has since then been the third political party. On the other hand, the PSD in the same year achieved its first absolute majority with 62.4% of the votes. After the 2013 municipal elections, five councilmen were members of the centre-right Partido Social Democrata (PSD), three of the centre-left Partido Socialista (PS) and one of the right-wing Centro Democrático e Social - Partido Popular (CDS-PP). The mayor is Aires Pereira, for the PSD, elected with 46.01% of the votes. The PSD holds the majority of public offices both in the Municipal Assembly and in the administrative parishes. Póvoa de Varzim Assembly is singly elected and comprises 27 members, with the PSD holding 14 seats, the PS 8, the CDS 4 and the left-wing CDU, 1.[60]

Póvoa de Varzim is the northernmost municipality in the Porto Metropolitan Area, about 27 km (17 mi) north of Porto. However, it is not a Porto's Commuter town.[35] Póvoa de Varzim is also part of the Association of Municipalities of the Ave Valley, along with neighbouring cities such as Vila do Conde, Guimarães, and Famalicão, with which it has the most important modern demographic links.

Since the establishment of the County of Portugal around 1095, Varzim was an administrative and military unit that stretched from the sea to Cividade de Terroso and São Félix Hills.[10][16][61][62] Póvoa de Varzim was established as a municipality in 1308 with the election of a town hall judge and boundary exemption.[14] As the town achieved broad self-government in the 16th century, restricted borders were created, which split the town itself and since disputed by the town hall. Over time, these were expanded to approach the medieval lordship boundaries.[63] However, Caxinas and Poça da Barca, south expansion areas of Póvoa de Varzim in the 18th and 19th centuries with fisher populations from Póvoa, are administrated by Vila do Conde, in spite of the centuries-old requests of Póvoa de Varzim for these to be incorporated in its municipality.[37][64] Inland, the parishes of Rio Mau, Touginhó, and Arcos are also historically disputed.[14]

The origin of the coat of arms of Póvoa de Varzim is unknown, but it certainly has local traits and symbolism. The coat of arms consists of a golden sun and a silver moon; in the middle a golden cross completed by two anchor silver arms, representing safety at sea. Over the cross, a ring, of which falls a golden rosary that interlaces with the anchor arms, representing faith and divine protection. The crest is made of five silver towers due to its city status. The flag is broken in blue and white. Between 1939 and 1958, a different coat of Arms and flag were used, which the population criticized; it consisted of a golden shield, covered by a red net, the sea and a black Poveiro boat; the flag was plain red. The population did not accept these new symbols and years later the old ones would be restored.

Cityscape

Urban morphology

Located in the coastal plain between the sea and hills, the city of Póvoa de Varzim has eleven Partes (parts), or districts. These districts are, in turn, part of two formal administrative structures known as freguesias (civil parishes): U.F. Póvoa de Varzim, Beiriz e Argivai and U.F. Aver-o-Mar, Amorim e Terroso.[23][65][66] To the south, the city is extending out to combine with Vila do Conde.[14][37]

The city started from an inland town that extended to the coast. The Bairro da Matriz, whose nucleus was the centre from whence the city grew, is intersected by 14th century narrow and twisted streets lined by single family homes. The historical district has old buildings such as the sixteenth-century house in front of Matriz Church — the main church, the old Town Hall (14th century), the seventeenth century Solar dos Carneiros and house of Captain Leite Ferreira, and the eighteenth century Limas and the Coentrão Houses. The fishermen were grouped in the south coast, around Póvoa Cove (Enseada da Póvoa); The fisher district was already developed in the 18th century with its structure of narrow streets parallel to the coast.[23]

Póvoa de Varzim City Centre or Centro is dominated by the service sector and by the shopping streets of Junqueira and Mousinho de Albuquerque Avenue. Praça do Almada, the central square, is tipped by City Hall, municipal departments, banks and other services. In the middle of the square, to the west, the Manueline pillory of Póvoa de Varzim stands. The Pelourinho, granted to the town in 1514, is a national monument representing the municipal emancipation of Póvoa de Varzim.

Bairro Norte, the beach district, is north of town and is densely occupied.[23] Continuous to this area, the Agro-Velho beach district, mostly known as Nova Póvoa, is the area of the city with most high-rises, the largest of which the Nova Póvoa, with 30 floors and 95 metres (312 ft) high, complete in 1979, was the tallest building in Portugal until the year 2000 and is still today one of the five tallest buildings. Close at hand, Barreiros and Parque da Cidade are districts from the latest expansion.[23]

Inland, Giesteira, derived from the old village of Giesteira that, with Argivai, formed the main nucleus of the settlement before the 14th century, and whose lavradores (farmers) set up "Póvoa" in the coast. Argivai is divided by the Santa Clara Aqueduct, the second largest aqueduct in Portugal, construction started in 1626. The old areas of Mariadeira, Regufe, Penalves, and Gândara have modest development, possess different topologies and are residential with small central areas.[63] The Regufe Quarter has as symbol the Regufe Lighthouse, a sample from the 19th century iron art. Aver-o-mar is the northernmost urban coastal district and also of residential nature, with the exception of Santo André also known as Quião, which keeps an untouched fishing character recognized by family homes that have grown up in a spontaneous way.[23]

Of the diverse religious buildings the 18th century Baroque churches are prominent: the Matriz Church, the Senhora das Dores Church and its six chapels, and the fishermen Lapa Church, with its curious Lapa Lighthouse. On the other hand, Misericórdia Church and Coração de Jesus Basilica denote the preference for the Neoclassical style in the end of the 19th century. The Romanesque revival style can be seen in São José de Ribamar.

Beaches and parks

Póvoa de Varzim's beach is a 12 km, or 7.5 mi (12.1 km), stretch, forming sheltered bays and divided by rocks, rich in iodine. Most beaches in the city are family-oriented such as Redonda, Salgueira or Lagoa Beach and during the summer period it can get crowded while those away from the city core, such as Santo André, are less crowded. Salgueira and Aguçadoura are surfing beaches. Located near a camping park, Rio Alto Beach is chosen by naturists given its difficult access and the privacy offered by the sand dunes.[67]

The Póvoa de Varzim City Park is almost entirely landscaped and includes hills, an island, small ponds, a stream, and a lake shaped by man. It has great lawn areas, rustic buildings and amphitheatres. It is a popular place for jogging, cycling and birdwatching. It stretches from the A28 freeway to Pedreira Lake.[68]

Espaço Agros is a private-sponsored park with 22 hectare in the former Anjo woodland that kept the essential rural values of the location, with some landscaping and environmental improvements, such as a lake.[69] Damaged by the construction of high speed roads, the woodland is expected to get a further 5.2 hectare public parkland.[23][28]

São Félix Hill (Monte São Félix), with iconic panoramic views over the city and the countryside, is a religious and forested hill that has the Senhora da Saúde Sanctuary at the foot of the hill and São Félix church at the summit. There's a gardened stairway throw the hill's slope. Rates Park is an adventure-camp with sport activities, canopy walkways, ecotourism by foot, horse, all-terrain vehicles or mountain biking.

Countryside

The green belt of Póvoa de Varzim includes a web of 98 localities in the parishes of Aguçadoura, Amorim, Balazar, Beiriz, Estela, Laundos, Navais, Rates, and Terroso. São Pedro de Rates, Codixeira, Aldeia, Pedreira, Fontainhas, Areosa, Teso, and Santo André de Baixo are the main rural communities, but there are tiny villages, such as Além, Calves, Gestrins, Gresufes, Passô, Sejães, and Crasto.

Terroso, Amorim and Beiriz are located in the urban hinterland. Beiriz has the notorious Beiriz carpets and diverse old country estates such as villas and a tapada, a hunting park, while Amorim is known for the bread eaten at high temperatures just after being made — the Broa de Amorim. The hills of Póvoa de Varzim: Cividade and São Félix are located in Terroso and Laúndos, respectively. On the first hill, there is Cividade de Terroso, with 3 thousand years was one of the major Castro culture cities, and the eremite Saint Félix is thought to have lived on the second hill during the Middle Ages.[70]

Rates was a small town during the Middle Ages which developed around the monastery established by Count Henry in 1100 on the site of an older temple and gained importance due to the legend of Saint Peter of Rates, first bishop of Braga, becoming a central site in the Portuguese way of Saint James.[71] Of the millenarian monastery, the São Pedro de Rates Church remains and is one of the oldest and best preserved Romanesque monuments in Portugal and is classified as national monument since 1910. Bordering Rates, Balazar became a Christian pilgrimage destination in the 20th century due to Alexandrina Maria da Costa, died 1955, who gained fame as a Saint,[72] beatified by Pope John Paul II.[73]

The northern sandy land of the municipality, Aguçadoura, Navais, and Estela is the farming area of Póvoa de Varzim, supplying the European markets with horticultural goods.[74] In old times, the population attributed legends, magical virtues or therapeutic effects to several springs. In Navais, there is the very ancient Moura Encontada Fountain, associated with Moura — a feminine water deity and guardian of enchanted treasures.[75]

Culture and contemporary life

Junqueira is Póvoa de Varzim's busiest shopping district, that cater to both the daily needs of residents and visitors. The main street, a shopping street since the 18th century, is a pedestrian area since 1955, one of the earliest in Portugal, and a model for other Portuguese cities that later did similar developments.[76] It has about 1 km (0.62 mi) of pedestrian streets. Dotted with boutiques in old traditional buildings, Junqueira is renowned for its jewellery, with Ourivesaria Gomes is a well known goldsmith in Portugal.[77]

People in Póvoa de Varzim observe a variety of festivals each year. The major celebration is Póvoa de Varzim Holiday, dedicated to Saint Peter. Neighbourhoods are decorated and, on the night of June 28 to 29, the population gathers in the streets and neighbourhoods compete in the rusgas carnival.[78] The population behaves much like football supporters, when defending their preferred quarter. Families who emigrated to the United States and beyond, have been known to come back to Póvoa, time and again, simply to relish the spectacular feelings of excitement and community present at this festival. Easter Monday or Anjo festival is a remnant of a pagan festival, formerly called "Festa da Hera" (The Ivy Festival), in which several family picnics are held in the woods.[20]

Carnival is a traditional festival in Póvoa de Varzim with the old Carnival Balls, masked people gathering in Rua da Junqueira until the late 1970s which led to the 1980s expensive carnival parades in the waterfront. The remains of such organized events are now celebrated spontaneously by the people who gather for a parade in Avenida dos Banhos. Despite not having any sort of advertising or media coverage, Póvoa's "Spontaneous Carnival" (Carnaval dos espontâneos) started to attract thousands of people.[79]

Póvoa de Varzim's waterfront is a beach and nightlife area popular with tourists and locals alike. Avenida dos Banhos, along Redonda and Salgueira beaches, is an iconic avenue, with nightclubs, bars, and esplanades along the way. Passeio Alegre is a beach square filled with esplanades and nearby Caetano de Oliveira Square, to the north, is a small lively square, with several bars where younger Povoans meet, before going on to the nightclubs. Póvoa has an LGBT-friendly history since the late 1990s, and held the Northern Portugal Pride, the first city in the North to held a gay pride festival, which ended in 2005, due to climbing rental prices. It was organized by former Hit Club and ILGA Portugal.[80]

Póvoa de Varzim has been a writers Mecca since the 19th century, gathering in tertulia sessions. Famous writers closely associated with the city are Almeida Garrett, António da Costa, Ramalho Ortigão, João Penha, Oliveira Martins, António Nobre, Antero de Figueiredo, Raul Brandão, Teixeira de Pascoaes, Alexandre Pinheiro Torres, and Agustina Bessa-Luís. However, the city is mostly remembered as the birthplace of Eça de Queiroz, one of the main writers in the Portuguese language. Camilo Castelo Branco wrote part of his life's work in former Hotel Luso-Brazileiro and José Régio wrote most of his work in Diana Bar, currently the beach library.[81]

In modern times, the city gained international prominence with Correntes d'Escritas, a literary festival where writers from the Portuguese and Spanish-speaking world gather in a variety of presentations and an annual award for best new release.[82] Latin American writer Luis Sepúlveda or the Africans Mia Couto and Ondjaki became associated with the city.[83][84]

Entertainment and performing arts

Casino da Póvoa is a gaming and entertainment venue since the 1930s. In 2006, it was the second casino in revenues, with 54 million euros and the third most popular with 1.2 million customers.[85] The casino has several bars, a live performances bar, a theater and restaurants, including haute cuisine of local and Portuguese inspiration. In the 19th century, Póvoa had over a dozen gambling venues, such as Salão Chinês, Café Suisso, Café David, Café Universal and Luso-Brasileiro. Póvoa de Varzim has hotels. The most historic of which is the Grande Hotel da Póvoa, built in the 1930s, an arresting modernist building and, siding it, the Hotel Luso-Brasileiro, the oldest in town, running since the 19th century, other 19th century former hotels are found in the city such as Hotel Universal in Praça do Almada.

Póvoa's theatrical tradition can be traced to 1793 when Italian operas and Portuguese comedies were presented in a theatre built in Campo das Cobras.[8] It developed with Teatro Garrett (1873) and Teatro Sá da Bandeira (1876).[14] The Varazim Teatro is a cultural and youth group of amateur theatre that has encouraged local drama with its own space known as Espaço D'Mente. Póvoa de Varzim Auditorium houses the local school of music and the Póvoa de Varzim Symphony Orchestra, which is the resident orchestra during the Festival Internacional de Música da Póvoa de Varzim, an event established in 1978.[86] Póvoa de Varzim Music Hall is the residence of Banda Musical da Póvoa de Varzim (1864) and its pops orchestra.

The Póvoa de Varzim Bullfighting Arena is used for Portuguese-style bullfighting, horse shows, and concerts. The most important run in the local bullring is known as Grande Corrida TV Norte (TV's Great Run - North) in late July. Others runs are held, such as 18th century-style Gala runs, with horsewomen,[87] or weaponless Garraida, with young bulls and Porto students.[88]

Museums

The Ethnography and History Municipal Museum of Póvoa de Varzim (1937) on Rua Visconde de Azevedo houses archaeological finds and exhibits relating to the seafaring history of the city. it is one of the oldest ethnic museums in Portugal and the "Siglas Poveiras" exhibit won the 1980 "European Museum of The Year Award". It possesses ancient sacred art, Poveiro boats and archaeological finds such as Roman inscriptions and Castro culture pottery.[89]

Themed museums exist: Santa Casa Museum with a religious theme, the Museum Nucleus of the Romanesque Church of Saint Peter of Rates, the Archaeological Nucleus of Cividade de Terroso, and the Bullfighting Museum located in Póvoa de Varzim bullring. Another two museums are due to open: Casa do Pescador (Fisherman home) and Farol de Regufe (Regufe lighthouse).

Small art galleries housing contemporary works of art are located in Casino da Póvoa, which exhibits paintings from some of the finest Portuguese artists, and the Ortopóvoa Art Gallery, bordering the Municipal Museum. An arts cooperative created in 1935, A Filantrópica has as its purpose the execution of cultural activities and inducement to artistic creation.[90]

The Rates Ecomuseum is a historical and countryside route, with various stops starting on the Praça (the Square) with the Senhor da Praça baroque chapel, the Rates pillory and the old Rates township house, and primordial springs, wind and water mills, rustic ways and houses.[91] The Arquivo Municipal is the city's archive planned for those who are interested in tracing their family pedigree chart or scrutinize the city's records.[92]

Ethnography

The culture of Póvoa de Varzim derives from different working classes and with influences arriving from the maritime route from the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean. The docudrama film Ala-Arriba! by José Leitão de Barros, popularized this unique Portuguese fishing community within the country during the 1940s. The local expression ala-arriba means "go upwards" and it represents the co-operation between the inhabitants.[93]

Siglas Poveiras are a form of proto-writing system, with a restricted number of symbols that were combined to form more complex symbols; these were used as a rudimentary visual communication system, and as a signature to mark belongings. Merchants wrote them in their books of credit; fishermen used it in religious rituals by marking them in the door of Catholic chapels near hills or beaches; in the table of the church during marriage and in their tombstone; and also had magical significance, such as the São Selimão sigla, that could be used as a protecting symbol and not as family mark.[94] Children used the same family mark with piques as a form of cadency. The youngest son would not have any pique and would inherit his father's symbol.[95] The siglas are still used, though much less commonly, by some families; and are, possibly, related with Viking traditions.[94]

The Poveiro is a specific genre of boat characterized by a wide flat-bottom and a deep helm. There were diverse boats with different sizes, uses and shapes. The most notable of which, the Lancha Poveira, was believed to be derived from the Drakkar Viking, but without a long stern and bow and with a lateen sail. Each boat carried carvings, namely a sigla poveira mark for boat identification and magical-religious protection at sea. According to a tradition that persists to this day, the youngest son is the heir of the family, as in old Brittany and Denmark, because it was expected that he would take care of his parents when they became old.[13] Women govern the family, because men were usually away from home fishing.[96]

The Branqueta is the traditional dress of the fishermen of Póvoa de Varzim. The Camisola Poveira are pullovers, part of the dress, that have fishery motifs in white, black and red, with the name of the owner embroidered in siglas poveiras. Other dresses include the urban tricana poveira for women and children's catalim caps. Handicrafts include the Tapetes de Beiriz rustic carpets.[97]

Formerly, the population was divided into different "castes", Lanchões, Rasqueiros, and Sardinheiros which were stratified depending on their Poveiro boat and fisheries caught. Apart from them, the Lavradores (the farmers) and the Sargaceiros and Seareiros, who went to the sea searching for fertilizers. As a rule, the groups remained distinct, and mixed marriages between them were forbidden, mostly because of the isolationism of the fishermen.[93][98]

São Félix Hill is a reference point for fishermen at sea and on the last Sunday of May, there is the Pilgrimage of Nossa Senhora da Saúde (Our Lady of Good Health) which covers a distance of 7 km (4.3 mi) between the Matriz Church and the hill. In Cape Santo André there is the Saint's Rock, which has a mark that the Povoan fishermen believe to be a footprint of Saint Andrew. The saint is seen as the "Boatman of Souls", fishing the souls of those who drown in the sea after a shipwreck, and helped in fisheries and marriages. The procession to the cape occurs on the dawn of the last day of November, when groups of men and women, wearing black hoods and holding lamps, go to the chapel via the beach. On August 15, the pinnacle of the fishermen's Feast of the Assumption occurs in the seaport with carefully arranged boats and fireworks.[99] In Mid-September, there's the Senhora das Dores festival with the century-old Pottery Fair.[100]

Cuisine

The most traditional ingredients of the local cuisine are locally-grown vegetables and fish. The fish used in the traditional cuisine are divided in two categories, the "poor" fish (sardine, ray, mackerel, and others) and the "wealthy" fish (such as whiting, snook, and alfonsino). The most famous local dish is Pescada à Poveira (Poveira Whiting), whose main ingredients are, along with the fish that gives the name to the dish, potatoes, eggs and a boiled onion and tomato sauce. Other fishery dishes include the Arroz de Sardinha (sardine rice), Caldeirada de Peixe (fish stew), Lulas Recheadas à Poveiro (Poveiro stuffed squids), Arroz de Marisco (seafood rice) and Lagosta Suada (steamed spiny lobster). Shellfish and boiled iscas, pataniscas, and bolinhos de bacalhau are popular snacks. Other dishes include Feijoada Poveira, made with white beans and served with dry rice (arroz seco); and Francesinha Poveira made in long bread that first appeared in 1962 as fast food for holidaymakers.[101]

Restaurants specializing in Portuguese barbecued chicken, seafood, francesinha, bacalhau can be found along the Estrada Nacional 13 road and other areas of the city.

Sports

The city has developed a number of sporting venues and has hosted several national, European and world championships in different sports. 38% of the population practiseF sport, a high rate when compared to the national average.

The most popular sport in Póvoa de Varzim is association football. The city is home to Varzim SC, a professional football club, who play in Estádio do Varzim on the North Side. City Park's Stadium and surrounding football fields are the main stage for Póvoa de Varzim's People's championship where its football clubs compete: Aguçadoura, Amorim, Argivai, Averomar, Balasar, Barreiros, Beiriz, Belém, Estela, Juve Norte, Laundos, Leões da Lapa, Mariadeira, Matriz, Navais, Rates, Regufe, Terroso, and Unidos ao Varzim.[102]

Swimming is the second most practised sport. The International Meeting of Póvoa de Varzim, in long course pool, is part of the European winter calendar.[103] The meeting occurs in the city pool complex belonging to Varzim Lazer, a municipal company that also runs other sports venues found north of the city: the tennis academy, the bullring, and the municipal pavilion. The other complex is property of Clube Desportivo da Póvoa, a club that is notorious, in the city, because it competes in several sports: rink hockey, volleyball, basketball, auto racing, and athletics. Other small clubs for other sports exist: Clube de Andebol da Póvoa de Varzim in Handball, Póvoa Futsal Club in Futsal and Póvoa de Varzim and Vila do Conde united clubs exists for Baseball and American Football, Villas Vikings and Villas Titans, respectively. Beach volley and Footvolley are more popular sports, and it was in Póvoa that footvolley was, for the first time, practiced in Portugal.[104]

The marina, near the seaport, offers sea activities developed by the local yacht club - the Clube Naval Povoense. Costa Verde Trophy, linking Póvoa and Viana do Castelo, is one of the regattas organized by the club and Rally Portugal yacht racing is a sailing and sightseeing event along the west Iberian coast.[105]

The Grande Prémio de São Pedro (Saint Peter Grand Prix), which occurs in the city's streets during the summer, is part of the national calendar of the Portuguese Athletics Federation.[106] In 2007, the Grande Prémio da Marginal (Waterfront Grand Prix), an annual event between Póvoa de Varzim and Vila do Conde, aiming for the funding of the National Association of Paramiloidosis.[107] The Cego do Maio Half Marathon aims at the promotion of the city and the sport activity among the population. In Cycling it hosts the Clássica da Primavera (Spring Classic) in April. Mountain bike events are common. There is a links golf course, a greyhound racing, and a shooting camp in the outskirts.

Due to its location and suitable urban areas, board culture is omnipresent in Póvoa de Varzim. Bodyboarders and surfers meet at Salgueira Beach. In Lota, a recreation area for several audiences, is especially popular amongst the skater and biker communities, and is considered the most charismatic skater area in the country.[108]

Media

O Comércio da Póvoa de Varzim (est. 1903), A Voz da Póvoa (est. 1938), and Póvoa Semanário, which appeared during the 1990s, are Póvoa de Varzim's major weekly newspapers; while the Gazeta da Póvoa de Varzim (1870–1874) was the first local newspaper. Most are dedicated to local news and have Internet editions.

The local radio stations Rádio Mar (89.0) and Radio Onda Viva (96.1) broadcast on FM and online. The stations' programming include local news and sports and feature an in-depth look at the city's top news by interviewing a guest at lunchtime on weekends. Radio Onda Viva airs Mandarin Chinese programming daily. The radio station, Rádio Mar, and the newspaper Póvoa Semanário belong to the same group; the same company offers news services to the neighbouring cities of Vila do Conde and Esposende.

Education

Higher education has limited history and availability. The Superior School of Industrial Studies and Management (ESEIG), part of Porto Polytechnic, was founded in 1990. The school was based in two campuses, one in Avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque and another one in Vila do Conde, but it was united in a single campus in 2001. The new campus has 31,544 square metres (7.795 acres) and includes facilities such as an auditorium and research space. ESEIG offers undergraduate and post-graduate education. Academic choices are centered around industrial engineering, industrial design, biomedical engineering, management, human resources, accountancy, and corporate finance.[109]

Póvoa de Varzim has public, denominational and independent schools in the city and outskirts. Public education in the municipality is provided by five school districts: Flávio Gonçalves, Cego do Maio, Aver-o-Mar, Campo Aberto, and Rates. These school districts arrange kindergartens and schools to the 9th grade of different locales of the municipality and are headed by Escolas de Educação Básica do 2.° e 3.°Ciclo (6th to the 9th grade schools) that give the name to each district.[110] Private schools are primarily run by Catholic parishes or groups, but the Grande Colégio da Póvoa de Varzim and Campo Verde School of Agriculture are eminent independent schools and MAPADI is a large facility and school for children with down syndrome. Colégio do Sagrado Coração de Jesus, where Agustina Bessa-Luís studied and developed her writing style, reopened in the 2007-2008 school year, planning to become a leading catholic school.

High schools (10th to the 12th grade) are situated in the school section at Póvoa city centre: Escola Secundária Eça de Queirós and Escola Secundária Rocha Peixoto. The Colégio de Amorim is an independent school in the outskirts that also offers secondary education. Eça de Queirós was a lyceum created in 1904 that maintains its humanist outlook and Rocha Peixoto was a former industrial and commercial school created in 1924.

The Rocha Peixoto Municipal Library, established in 1880, on the 300th anniversary of the death of Luís de Camões was housed in the current building in 1991. Small suburban library branches and Diana Bar Library are extension posts of the municipal library. A little more than one quarter of the population now has intermediate or superior level qualifications. The illiteracy level was 5.9 percent in 2001.

Infrastructure

Healthcare and security

The first healthcare structure, the Santa Casa da Misericórdia da Póvoa de Varzim (Holy House of Mercy), opened in 1756. The hospitals of the city are the São Pedro Pescador Hospital (state-run) and Clipóvoa Hospital (private). The public hospital suffers from lack of bed spaces. Due to this, it underwent expansion works and there is an ongoing plan to build a modern hospital, in the border between the cities of Póvoa de Varzim and Vila do Conde, to serve the population of both municipalities. The Centro de Saúde da Póvoa de Varzim (Health Centre) is a public primary care building which has extensions in the main suburbs.

The Municipal Police of Póvoa de Varzim, one of the first to be established in the country, is an administrative police force that acts solely within the municipality and reports directly to the mayor. The Polícia de Segurança Pública (PSP) does the city policing, while the Guarda Nacional Republicana (GNR) is responsible for the countryside. Regarding crime, Póvoa de Varzim is considered by the Polícia de Segurança Pública as a "calm" zone in all categories of offense; violent crime, in particular, is practically non-existent. Mostly, crime consists of minor robberies to homes, stores, or from cars.[111]

Póvoa is one of the twelve national sea borders controlled by the Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras (SEF). The Escola Prática dos Serviços, just east of the city by the A28 motorway, is the national headquarters for military administration instruction, with the Battalion of Military Administration, and, due to the reorganization of army services, the former Escola Prática de Administração Militar, from 2006 onwards it gained the material and transport services, thus increasing its range of functions and troop numbers.[112]

Transport

Póvoa de Varzim is served by a transportation network that employs maritime, aerial and terrestrial travel. The terrestrial access infrastructure is composed of national motorways (freeways), the national roads system, and light rail metro. These infrastructures and the airport, bus terminal, marina and harbour are daily used by commuters.

Public transportation within the city is provided by private-owned companies. The Central de Camionagem is a terminus for urban and long distance buses that provide mass transit in the surrounding region, namely the city's countryside, Porto, Minho Region, and Galicia in Spain. Litoral Norte as a wholly urban transportation network with 5 lines, while Linhares has the oldest bus network operating in the city, now owned by Transdev.[113]

The Francisco Sá Carneiro Airport (LPPR, better known as Porto Airport) is located 18 km (11 mi) south of the city. It is one of the busiest international airports in Portugal and serves all Greater Porto. Póvoa Aerodrome, officially known as S. Miguel de Laundos, is small-sized, with only 270 meters long for ultralight aviation and other small planes.

Line B of Porto Metro links Póvoa de Varzim to Porto and the airport with two services: a standard and a shuttle (the Expresso); through Verdes station, Metro trains link the city and the airport.[114] The line operates on a former railway, which opened in 1875 and closed in 2002 to give way for the metro. The railway network was expanded and reached Famalicão in 1881, it was closed entirely in 1995 and became a rail trail.[115]

The city is connected by road on a north-south axis from Valença, Viana do Castelo, and Esposende to Porto by the A28 motorway. It is also reached by the A7 (from Guimarães and Vila Nova de Famalicão) and A11 (from Braga and Barcelos) motorways on an east-west axis, through the south and north of the city, in that order, and both cross the A28. Although it lost usefulness for average and long distances, the National Roads system has acquired municipal interest: EN13 that cuts the city in half, in a north-south direction, is used by commuters originating from the northern suburbs and from the city of Vila do Conde, in the south, to travel downtown. The EN205 and the EN206 are used by commuters starting from the interior of the municipality.[23]

The traditional road system of the city, composed of roads that run parallel in the direction of the sea, can be seen in any of the following avenues: Avenida do Mar, Avenida Vasco da Gama, Avenida Mouzinho de Albuquerque, and Avenida Santos Graça. The Avenida dos Descobrimentos and Avenida dos Banhos, in other hand, run parallel to the coast. The growth of the city inland and northwards made ring roads more important, this can be seen in Avenida 25 de Abril, an urban belt road.

Sister cities

Within the European Union, Póvoa de Varzim is twinned, since 1986, with the city of Montgeron in France, with Eschborn in Germany (since 1998) and Żabbar in Malta (since 2001) and it received, due to the partnership with other European cities, the 1995 and 2005 Golden Stars of Town-twinning from the European Commission.[116]

In Brazil, Póvoa de Varzim is twinned with major cities. It is twinned with Rio de Janeiro since 1989,[117] it also built town-twinning links with the city of São Paulo. These metropolises hold Casa dos Poveiros, voluntary associations of immigrants from Póvoa de Varzim. The one from Rio was established in 1930 and the one from São Paulo in 1991.

See also

- List of notable residents of Póvoa de Varzim

- Sculptures in Póvoa de Varzim

- Landmarks in Póvoa de Varzim

- Aguçadora Wave Park

References

- ↑ "População residente (N.°) por Municípios - 2007" (in Portuguese). INE (Statistics Portugal). Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ↑ "Povoa de Varzim." Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911).

- 1 2 3 "Póvoa de Varzim." (in Portuguese) Grande Enciclopédia Universal (2004), vol. 16, pp. 10683-10684, Durclub

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Flores Gomes, José Manuel & Carneiro, Deolinda (2005). Subtus Montis Terroso — Património Arqueológico no Concelho da Póvoa de Varzim (in Portuguese). CMPV.

- ↑ "Portal do Arqueólogo - Laundos" (in Portuguese). IGESPAR. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ↑ Ferreira da Silva, Armando Coelho (1986). A Cultura Castreja no Noroeste de Portugal (in Portuguese). Museu Arqueológico da Citânia de Sanfins.

- 1 2 Barbosa, Viriato (1972). A Póvoa de Varzim, 2.ª edição (in Portuguese). Póvoa de Varzim.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Amorim, Sandra Araújo (2004). Vencer o Mar, Ganhar a Terra. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ↑ Autarcia e Comércio em Bracara Augusta no período Alto-Imperial

- 1 2 3 Barroca, Mário Jorge. "Fortificações e Povoamento no Norte de Portugal (Séc. IX a XI)" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Portugalia Nova Série, Vol XXV. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Freguesia: Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Mosteiro do Salvador de Vairão" (in Portuguese). Arquivo Nacional Torre do Tombo. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Barco Poveiro" (in Portuguese). Celtiberia. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Baptista de Lima, João (2008). Póvoa de Varzim - Monografia e Materiais para a sua história. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ↑ "A História da Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). Portal da Póvoa de Varzim. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Estudos de Cronologia: Os mais antigos documentos escritos em português - Instituto Camões

- ↑ Amorim, Manuel (2003). A Póvoa Antiga. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ↑ Costa, António Carvalho da (1706). Corografia portugueza e descripçam topografica do famoso reyno de Portugal. Tomo I, Tratado IV, Cap. XV "Da Villa da Povoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Off. de Valentim da Costa Deslandes. p. 409. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Fangueiro, Óscar (2008). Sete Séculos na Vida dos Poveiros. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- 1 2 3 Azevedo, José de (2008). Poveirinhos pela Graça de Deus. Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ↑ Memorias economicas. Academia real das sciencias de Lisboa. 1812.

- ↑ Projecto para a Construção de Pavilhões na Praia da Póvoa (Maio a Junho de 1924) - Arquivo Municipal da Póvoa de Varzim (2008)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Relatório do Plano de Urbanização da Póvoa de Varzim (in Portuguese) — CMPV, Departamento de Gestão Urbanística e Ambiente

- ↑ Azevedo, José (February 27, 2006). "Missa para lembrar tragédia no mar poveiro". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Eventos: Dia da Cidade" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Turismo: Conhecer a Póvoa, História" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- 1 2 Gomes, Paulino, coord. (1998). Póvoa de Varzim, Um Pé na Terra, Outro no Mar. Anégia Editores.

- 1 2 "Caracterização ambiental do Concelho da Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). Portal da Póvoa de Varzim. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ↑ McKnight, Tom L; Hess, Darrel (2000). "Climate Zones and Types: The Köppen System". Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 200–1. ISBN 0-321-61687-1.

- ↑ Araújo, Maria da Assunção. "O clima da região do Porto". Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ↑ "PBH do Rio Ave - Volume III – Análise" (in Portuguese). Administração da Região Hidrográfica do Norte. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ↑ Borges, Júlio. A Paisagem Poveira.

- ↑ "Recenseamento Geral da População e da Habitação dos censos de 1864, 1878, 1890, 1900, 1911, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1981, 1991 e 2001". Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ↑ Fernando Nunes da Silva (2005), Alta Velocidade em Portugal, Desenvolvimento Regional PDF (2.27 KB), CENSUR, IST

- 1 2 3 INE (2003), Movimentos Pendulares e Organização do Território Metropolitano: Área Metropolitana de Lisboa e Área Metropolitana do Porto 1991-2001, Lisboa

- 1 2 3 INE (2005), Grande Área Metropolitana do Porto — Porto Metropolitan Area, Lisbon

- 1 2 3 Gentes de Ferro em Barcos de Pau – CMPV

- ↑ ""Biblioteca Poveira" recebe nova obra em Dia Nacional do Mar". CMPV. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ Teixeira Marques, Ângelo (February 14, 2007). "Câmara da Póvoa cria gabinete da migração". Público (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Santos, Angélica, and Pinto, Miguel (18 April 2007). "Construção civil volta a disparar na cidade da Póvoa". Póvoa Semanário (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Fonseca Cardoso (1908). O Poveiro (in Portuguese). Portugália, t. II. Porto.

- ↑ Carleton Stevens Coon (1939). The Races of Europe. Chapter XI, section 15. ISBN 0-8371-6328-5.

- ↑ Lima Barreto (2000). Marginália - A Questão dos "Poveiros" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Virtual Books, Pará de Minas - MG.

- ↑ "Sete séculos na vida dos poveiros – nova obra prova a profusa linhagem do pescador poveiro". CMPV. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ↑ Silva, Hugo (September 2, 2006). "Grande Porto tem metade do desemprego do Norte". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Ford, Emily (July 8, 2008). "Wave power scientist enthused by green energy" (– Scholar search). Times online.

- ↑ "Wave energy contract goes abroad". BBC News. July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Trocado Marques, Ana (May 22, 2006). "Ondas vão dar energia a um terço do concelho". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Apresentação do Parque da Aguçadoura". Ocean Power Delivery Portugal S.A. Archived from the original on August 31, 2006. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ Gomes Sousa, Catarina (April 26, 2012). "Ondas de milhões abandonadas". Correio da Manhã (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Energía solar de origen ibérico". El Mundo (in Spanish). July 8, 2008.

- ↑ Rios, Pedro. "Em contraciclo. A Poveira quer aumentar a produção e está a contratar" (in Portuguese). Rádio Renascença. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ↑ "A Poveira investe 4,5 milhões numa nova fábrica na Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). Oje. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Produtos" (in Portuguese). A Poveira. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ↑ Martins, Hélder. "À procura de parceiros" (in Portuguese). Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Joint venture to supply deepwater mooring systems". Offshore. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Fomento económico: Parque Industrial de Laundos" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Archived from the original on February 16, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ Ruffa, Giovanni. "PremioSlowFood". Slow Food Foundation. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ↑ "Agros investirá 40 ME em Centro Empresarial que Ficará Concluído em 2008" (in Portuguese). Agros SGPS. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ Autárquicas 2013 - Resultados - Póvoa de Varzim Eleições

- ↑ ALMEIDA, Carlos Alberto Ferreira de (1978). Castelologia Medieval de Entre-Douro-e-Minho. Desde as Origens a 1220, diss. complementar de doutoramento (in Portuguese). Porto: policopiada, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto. pp. 25–27.

- ↑ ALMEIDA, Carlos Alberto Ferreira de (1992). Castelos Medievais do Noroeste de Portugal, Finis Terrae. Estudios en Lembranza do Prof. Dr. Alberto Balil (in Portuguese). Santiago de Compostela. pp. 382–383.

- 1 2 Amorim, Manuel (2003). A Póvoa Antiga (in Portuguese). Na Linha do horizonte - Biblioteca Poveira CMPV.

- ↑ A Voz da Póvoa N.° 1277 (in Portuguese), 2006-08-31

- ↑ "Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.° 15/2006" (in Portuguese). SIDDAMB. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Reorganização Administrativa territorial Autárquica: Póvoa de Varzim, nível 1" (in Portuguese). INE. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ↑ Trocado Marques, Ana (August 6, 2006). "Federação quer oficializar nudismo na praia da Estela". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Póvoa de Varzim inaugurou parque lúdico desenhado por Sidónio Pardal". Público (in Portuguese). June 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Edifício Sede" (in Portuguese). Agros. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Resumo histórico dos principais locais de interesse turístico" (in Portuguese). Turel. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ↑ Costa, António Carvalho da (1706). Corografia portugueza e descripçam topografica do famoso reyno de Portugal. Tomo I, Tratado V, Cap. IV "Da Villa de Rates" (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Off. de Valentim da Costa Deslandes. pp. 336–337. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Rev. Fr. Fabrice Delestre, The Angelus (June 2000 issue), Alexandrina of Portugal and the Consecration. — The Fatima Network. Accessed September 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Alexandrina Maria da Costa". Catholic Community Forum. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Aguçadoura" (in Portuguese). Portal da Póvoa de Varzim. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Conhecer a Póvoa: Lendas e Crenças" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Vera. "Um dia de festa na Rua da Junqueira (COM VÍDEO)" (in Portuguese). Póvoa Semanário. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ↑ "BCP entra na ourivesaria" (in Portuguese). Expresso. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ↑ "Conhecer a Póvoa: Festas populares e religiosas — São Pedro" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Carnaval dos espontâneos enche marginal" (in Portuguese). Póvoa Semanário. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Pride do Norte" (in Portuguese). Portugal Pride. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ↑ ""O Ardina, o Livro Sonhado" apresentado no Diana Bar" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Debate e entrega de prémios encerra 7°Correntes d`Escritas" (in Portuguese). RTP. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ↑ ""Os silêncios são parte da conversa" – Mia Couto apresentou Jesusalém" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ↑ ""AvóDezanove e o Segredo do Soviético" – Ondjaki veio à Póvoa apresentar novo livro" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ↑ "PORTUGAL: Casinos portugueses facturaram 400 milhões em 2006" (in Portuguese). Profissionais dos Casinos. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Confluências musicais no Festival da Póvoa" (in Portuguese). Diário de Notícias. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Tarde de touros, na Praça de Touros da Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Estudantes universitários estão contra as garraiadas académicas" (in Portuguese). Público. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Sobre o museu" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Cooperativa "A Filantrópica"" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- ↑ Trocado Marques, Ana (April 22, 2007). "Ecomuseu estende-se ao longo de oito quilómetros". Jornal de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Arquivo Municipal: fundo documental" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- 1 2 "Ala-Arriba! (1942)" (in Portuguese). Rascunho. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- 1 2 Lixa Filgueiras, Octávio (1965). Àcêrca das Siglas Poveiras (in Portuguese). IV Colóquio Portuense de Arqueologia.

- ↑ Santos Graça, António (1942). Inscrições Tumulares Por Siglas (in Portuguese). Author edition, Póvoa de Varzim.

- ↑ "Turismo: Conhecer a Póvoa, Siglas Poveiras" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Tapetes de Beiriz" (in Portuguese). Lifecooler. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Traje Poveiro - Os Lanchões" (in Portuguese). Garatujando. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Conhecer a Póvoa: Festas populares e religiosas — Nossa Senhora da Assunção" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Conhecer a Póvoa: Festas populares e religiosas — Nossa Senhora das Dores" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ Afonso Pereira, Sílvia (June 6, 2006). "As francesinhas à moda da Póvoa". Diário de Notícias (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Clubes" (in Portuguese). Associação de Futebol Popular da Póvoa de Varzim. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Cinco mínimos para o Europeu de Juniores" (in Portuguese). Federação portuguesa de Natação. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ↑ "Futevólei - História" (in Portuguese). Federação Nacional de Futevólei. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Rally Portugal - sailing and sightseeing". Sail World. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Regulamento" (in Portuguese). Atletas.net. Retrieved October 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Vila do Conde e Póvoa de Varzim unidas pelo Atletismo" (in Portuguese). Atletas.net. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ↑ "Póvoa de Varzim recebe segunda etapa do Circuito Nacional" (in Portuguese). O Jogo. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ "Cursos" (in Portuguese). Escola Superior de Estudos Industriais e de Gestão. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Estabelecimentos de Educação" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Criminalidade violenta passou ao lado da Póvoa e Vila". Póvoa Semanário (in Portuguese): 2. February 1, 2006.

- ↑ "EPS — Historical" (in Portuguese). Exército Português. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Nova linha de transporte liga Zona Industrial de Amorim a Vila do Conde" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ↑ "A Linha Vermelha chega à Póvoa" (in Portuguese). Metro do Porto. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ↑ "As Linhas de Porto-Póvoa-Famalicão e Guimarães: resumo histórico" (in Portuguese). Vialivre.org. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ↑ "As Cidades Geminadas, as Relações Internacionais e a Cooperação" (in Portuguese). CMPV. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ "http://www.povoasemanario.pt/index.php?page=news&idn=2782&city=" (in Portuguese). Póvoa Semanário. Retrieved December 3, 2010. External link in

|title=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Póvoa de Varzim. |

- Portal Municipal (Portuguese) - official city government site

- Portal da Economia (Portuguese) - Official site for business

- Tourist map (English)

| ||||||