Oxycodone

| |

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

(5R,9R,13S,14S)-4,5α-epoxy-14-hydroxy-3-methoxy-17-methylmorphinan-6-one | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Roxicodone, OxyContin, Oxecta, OxyIR, Endone, Oxynorm, OxyNEO |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682132 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Legal status |

|

| Dependence liability | High |

| Routes of administration | oral, intramuscular, intravenous, intranasal, subcutaneous, transdermal, rectal, epidural[1] |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–87%[2] |

| Protein binding | 45%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic: primarily CYP3A and to a lesser extent, CYP2D6 to oxymorphone[2] |

| Biological half-life | 2–4 hours.[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (83%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

76-42-6 |

| ATC code |

N02AA05 N02AA55 (in combinations) |

| PubChem | CID 5284603 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7093 |

| DrugBank |

DB00497 |

| ChemSpider |

4447649 |

| UNII |

CD35PMG570 |

| KEGG |

D05312 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:7852 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL656 |

| Synonyms | dihydrohydroxycodeinone, 14-hydroxydihydrocodeinone, 6-deoxy-7,8-dihydro-14-hydroxy-3-O-methyl-6-oxomorphine[3] |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C18H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 315.364 g/mol |

| |

| |

| Physical data | |

| Solubility in water | HCl: 166 mg/mL (20 °C) |

| (verify) | |

Oxycodone is a semisynthetic opioid synthesized from thebaine, an opioid alkaloid found in the Persian poppy and one of the many opioid alkaloids found in the opium poppy. It is a narcotic analgesic generally indicated for relief of moderate to severe pain. It was developed in 1917 in Germany[4][5] as one of several new semi-synthetic opioids in an attempt to improve on the existing opioids.[1]

Oxycodone is available as single-ingredient medication in immediate release and controlled release. Parenteral formulations of 10 mg/mL and 50 mg/mL are available in the UK for IV/IM administration.[6] Combination products are also available as immediate release formulations, with non-narcotic ingredients such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and paracetamol (acetaminophen); a combination with naloxone is available in managed-release tablets. The naloxone precipitates opioid withdrawal symptoms and blocks the faster onset were the tablet to be crushed and filtered for injection or otherwise tampered with in a manner not intended.

Medical uses

Oxycodone has been in clinical use since 1916,[1] and it is used for managing moderate to moderately severe acute or chronic pain.[7] It has been found to improve quality of life for those with many types of pain. However, prescribing errors, diversion and misuse can lead to severe addiction and accidental overdose possibly resulting in death.[8]

The controlled-release oral tablet form is intended to be taken every 12 hours.[9] Oxycodone is clearly useful for acute pain, as is the case with other opioids, and in some instances of chronic pain, cancer-related and otherwise. Experts are divided regarding the efficacy of all opioids in non-malignant chronic pain. Opioids induce acute pain relief, but most of them have the strong potential for dependence, withdrawal, and the induction of pain sensitivity and hyperalgesia, thereby causing the symptom (pain) that they are being used to treat.

An Italian study concluded from investigating multiple studies that controlled-release oxycodone is comparable to instant-release oxycodone, morphine, and hydromorphone in management of moderate to severe cancer pain. The study indicated that side effects appear to be less than those associated with morphine and that it is a valid alternative to morphine and a first-line treatment for cancer pain.[10]

In 2014, the European Association for Palliative Care recommended that oral oxycodone could be taken as a second-line alternative to oral morphine for cancer pain.[11]

Administration

In the United States, Oxycodone is medically approved only for administration orally, and is only supplied in the form of oral tablets and oral (liquid) concentrates. In the United Kingdom, Oxycodone is also medically approved for intravenous therapy (IV) and intramuscular (IM) injection. When first introduced in Germany in 1917, IV/IM became common for post-operative pain management of soldiers of the Central Powers during World War I.[1]

Off-label use

Oxycodone appears to have a significant anti-depressant effect.[12] However, its use for this purpose may be illegal: see Legal Status below.

Side effects

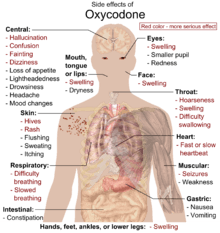

Common side effects include euphoria, constipation, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, anxiety, itching, and sweating.[14] Less common side effects (experienced by less than 5% of patients) include loss of appetite, nervousness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, urine retention, dyspnea, and hiccups.[15]

In high doses, overdoses, or in patients not tolerant to opiates, oxycodone can cause shallow breathing, bradycardia, cold-clammy skin, apnea, hypotension, miosis, circulatory collapse, respiratory arrest, and death.[15]

Oxycodone in combination with naloxone in managed-release tablets, has been formulated to reduce side effects.[16]

Dependence, addiction and withdrawal

The risk of experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms is high if a patient has become physically dependent or addicted and discontinues oxycodone abruptly. Therefore, particularly in cases where the drug has been taken regularly over an extended period, use should be discontinued gradually rather than abruptly. People who use oxycodone in a recreational, hazardous, or harmful fashion (not as intended by the prescribing physician) are at even higher risk of severe withdrawal symptoms, as they tend to use higher-than-prescribed doses. The symptoms of oxycodone withdrawal are the same as for other opiate-based painkillers, and may include "anxiety, panic attack, nausea, insomnia, muscle pain, muscle weakness, fevers, and other flu-like symptoms".[17]

Withdrawal symptoms have also been reported in newborns whose mothers had been either injecting or orally taking oxycodone during pregnancy.[18]

Hormone imbalance

As with other opioids, oxycodone (particularly during chronic heavy use) often causes temporary hypogonadism or hormone imbalance.[19]

Detection in biological fluids

Oxycodone and/or its major metabolites may be measured in blood or urine to monitor for clearance, abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Many commercial opiate screening tests cross-react appreciably with oxycodone and its metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish oxycodone from other opiates.[20]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

In 1997, a group of Australian researchers proposed (based on a study in rats) that oxycodone acts on κ-opioid receptors, unlike morphine, which acts upon μ-opioid receptors.[21] Further research by this group indicated the drug appears to be a κ2b-opioid agonist.[22] However, this conclusion has been disputed, primarily on the basis that oxycodone produces effects that are typical of μ-opioid agonists, mainly because oxycodone is metabolized in the liver to oxymorphone as a metabolite, which is a more potent opioid agonist with stronger/higher binding affinity to μ-opioid receptors compared to oxycodone.[23]

In 2006, research by a Japanese group suggested the effect of oxycodone is mediated by different receptors in different situations. Specifically in diabetic mice, the κ-opioid receptor appears to be involved in the antinociceptive effects of oxycodone,[24] while in nondiabetic mice, the μ1-opioid receptor seems to be primarily responsible for these effects.[25]

After oxycodone binds to the opioid receptor, a G-protein complex is released, which inhibits the release of neurotransmitters by the cell by reducing the amount of cAMP produced, closing the Ca++ channels, and opening the K channels.[26]

Absorption

After a dose of conventional oral oxycodone, peak plasma levels of the drug are attained in about one hour;[27] in contrast, after a dose of OxyContin (an oral controlled-release formulation), peak plasma levels of oxycodone occur in about three hours.[15]

Distribution

Oxycodone in the blood is distributed to skeletal muscle, liver, intestinal tract, lungs, spleen, and brain.[15] Conventional oral preparations start to reduce pain within 10–15 minutes on an empty stomach; in contrast, OxyContin starts to reduce pain within one hour.[7]

Metabolism

Oxycodone is metabolized to α and β oxycodol; oxymorphone, then α and β oxymorphol and noroxymorphone; and noroxycodone, then α and β noroxycodol and noroxymorphone (N-desmethyloxycodone).[27] (14-Methoxymetopon that in turn becomes 14-Hydroxydihydromorphine) These metabolites are true only for humans.[28] As many as six metabolites for oxycodone (14-hydroxydihydromorphinone, 14-hydroxydihydrocodeine, 14-hydroxydihydrocodeinone N-oxide {oxycodone N-oxide}, 14-hydroxydihydroisocodeine, 14-hydroxydihydrocodeine N-oxide, and noroxycodone) have been found in rabbits,[29] several of which are thought to be active metabolites to some extent, although a study using conventional oral oxycodone concluded oxycodone itself, and not its metabolites, is predominantly responsible for the drug's opioid effects on the brain.[27]

Oxycodone is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system in the liver, making it vulnerable to drug interactions.[15] Some people are fast metabolizers, resulting in reduced analgesic effect, but increased adverse effects, while others are slow metabolisers, resulting in increased toxicity without improved analgesia.[30][31] The dose of OxyContin must be reduced in patients with reduced hepatic function.[7]

Elimination

Oxycodone and its metabolites are mainly excreted in the urine and sweat; therefore, it accumulates in patients with renal impairment.[7]

Dosage and administration

Oxycodone can be administered orally, intranasally, via intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injection, or rectally. The bioavailability of oral administration of oxycodone averages 60–87%, with rectal administration yielding the same results; intranasal varies between individuals with a mean of 46%.[32]

Equivalency

Taken orally, the conversion ratio between morphine to extended release oxycodone is reported as 2:1.[33]

Chemistry

Oxycodone's chemical name is derived from codeine. The chemical structures are very similar, differing only in that

- Oxycodone has a hydroxyl group at carbon-14 (codeine has just a hydrogen in its place)

- Oxycodone has a 7,8-dihydro feature. Codeine has a double bond between those two carbons; and

- Oxycodone has a carbonyl group (as in ketones) in place of the hydroxyl group of codeine.

It is also similar to hydrocodone, differing only in that it has a hydroxyl group at carbon-14.[7]

Expanded expression for the compound oxycodone in the academic literature include "dihydrohydroxycodeinone",[3][34][35] "Eucodal",[34][35] "Eukodal",[1][36] "14-hydroxydihydrocodeinone",[3][34] and "Nucodan".[34][35] In a UNESCO convention, the translations of "oxycodone" are oxycodon (Dutch), oxycodone (French), oxicodona (Spanish), الأوكسيكودون (Arabic), 羟考酮 (Chinese), and оксикодон (Russian).[37] The word "oxycodone" should not be confused with "oxandrolone", "oxazepam", "oxybutynin", "oxytocin", or "Roxanol".[38]

In terms of biosynthesis, oxycodone has been found naturally in nectar extracts from the orchid family Epipactis helleborine; together along with another opioid: 3-{2-{3-{3-benzyloxypropyl}-3-indol, 7,8-didehydro- 4,5-epoxy-3,6-d-morphinan.[39]

History

Freund and Speyer of the University of Frankfurt in Germany first synthesized oxycodone from thebaine in 1916,[5] a few years after the German pharmaceutical company Bayer had stopped the mass production of heroin due to hazardous use, harmful use, and dependence. It was hoped that a thebaine-derived drug would retain the analgesic effects of morphine and heroin with less dependence. To some extent this was achieved, as oxycodone does not have the same immediate effect as heroin or morphine, nor does it last as long.

The first clinical use of the drug was documented in 1917, the year after it was first developed.[5][36] It was first introduced to the US market in May 1939. In early 1928, Merck introduced a combination product containing scopolamine, oxycodone and ephedrine under the German initials for the ingredients SEE, which was later renamed Scophedal (SCOpolamine ePHEDrine and eukodAL). This combination is essentially an oxycodone analogue of the morphine-based Twilight Sleep with ephedrine added to reduce circulatory and respiratory effects.

In the early 1960s the United States government classified oxycodone as a schedule II drug. In 1995 the FDA approved OxyContin.[40]

As of May 2013 an extended release version in the United States is only available as OxyContin brand.[41]

Statistics

The International Narcotics Control Board estimated 11.5 short tons (23,000 lbs) of oxycodone were manufactured worldwide in 1998;[42] by 2007 this figure had grown to 75.2 tons (150,400 lbs).[42] United States accounted for 82% of consumption in 2007 at 51.6 tons. Canada, Germany, Australia and France combined accounted for 13% of consumption in 2007.[42][43] In 2010, 122.5 tons of oxycodone were manufactured, according to the International Narcotics Control Board. This number had decreased slightly from the all-time high in 2009 of 135.9 tons.[44]

Recreational use

Effects

Oxycodone, like other opioid analgesics, tends to induce feelings of euphoria, relaxation and reduced anxiety in those who are occasional users.[45] These effects make it one of the most commonly abused pharmaceutical drugs in the United States.[46]

Preventive measures

In August 2010, Purdue Pharma reformulated their long-acting oxycodone line, marketed as OxyContin, using a polymer, Intac,[47] to make the pills extremely difficult to crush or dissolve[48] in water to reduce OxyContin abuse.[49] The FDA approved relabeling the reformulated version as abuse-resistant in April 2013.[50]

Pfizer manufactures a preparation of short-acting oxycodone, marketed as OXECTA, which contains inactive ingredients, referred to as tamper-resistant AVERSION® Technology.[51] It does not deter oral abuse. Approved by the FDA in the US in June 2011, the new formulation makes crushing, chewing, snorting, or injecting the opioid impractical because of a change in its chemical properties.[52]

Australia

The non-medical use of oxycodone existed from the early 1970s, but by 2015, 91% of a national sample of injecting drug users in Australia had reported using oxycodone, and 27% had injected it in the last six months.[53]

Canada

Opioid-related deaths in Ontario had increased by 242 per cent from 1969 to 2014.[54] By 2009 in Ontario there were more deaths from oxycodone overdose than from cocaine overdose,[55] Deaths from opioid pain relievers had increased from 13.7 deaths per million residents in 1991 to 27.2 deaths per million residents in 2004.[56] The abuse of oxycodone in Canada became a problem. Areas where oxycodone is most problematic are Atlantic Canada and Ontario, where its abuse is prevalent in rural towns, and in many smaller to medium-sized cities.[57] Oxycodone is also widely available across Western Canada, but methamphetamine and heroin are more serious problems in the larger cities, while oxycodone is more common in rural towns. Oxycodone is diverted through doctor shopping, prescription forgery, pharmacy theft, and overprescribing.[57][58]

The recent formulations of oxycodone, particularly Purdue Pharma's crush-, chew-, injection- and dissolve-resistant OxyNEO[59] which replaced the banned OxyContin product in Canada in early 2012, have led to a decline in the abuse of this opiate but have increased the abuse of the more potent drug fentanyl.[60] According to a Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse study quoted in Maclean's magazine, there were at least 655 fentanyl-related deaths in Canada in a five-year period.[61]

In Alberta, the Blood Tribe police claimed that from the fall of 2014 through January 2015, oxycodone pills or a lethal fake variation referred to as Oxy 80s[62] containing fentanyl made in illegal labs by members of organized crime were responsible for ten deaths on the Blood Reserve, which is located southwest of Lethbridge, Alberta.[63] Province-wide, approximately 120 Albertans died from fentanyl-related overdoses in 2014.[62]

United Kingdom

Abuse and diversion of oxycodone in the UK commenced in the early- to mid-2000s.[64] The first known death due to overdose in the UK occurred in 2002.[65] However, recreational use remains relatively rare.

United States

In the United States, more than 12 million people abuse opioid drugs.[66] In 2010, 16,652 deaths were related to opioid overdose in combination with other drugs such as benzodiazepines and alcohol.[67] In September 2013, the FDA released new labeling guidelines for long acting and extended release opioids requiring manufacturers to remove moderate pain as indication for use, instead stating the drug is for "pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long term opioid treatment."[68] The updated labeling will not restrict physicians from prescribing opioids for moderate, as needed use.[66]

Based on statistical estimates by the US Department of Health and Human Services, about 11 million people in the US will consume at least one dose of this opioid in a non-medical way illegally sold under slang names cotton, pills, kickers, or orange county.[69][70] About 100,000 men or women per year are admitted to US hospitals due to misuse of this drug, making it the most widely abused opioid substance in America. Diverted oxycodone is taken orally or ingested through insufflation, it can also be prepared for injection and administered intravenously, while some abusers will heat the pills on aluminum foil and inhale the smoke as a means of ingesting oxycodone. Other ways of abuse include intravenous injection of oral dosage forms, which are not designed for parenteral use. In 2008, oxycodone and hydrocodone misuse caused 14,800 deaths. Some of the cases, however, were due to the hepatotoxic effect of acetaminophen.[71]

The FDA authorized OxyContin, the extended-release form of oxycodone, for conditional use in children (pediatric use) as young as 11, for treatment of cancer pain, trauma pain, or pain due to major surgery; the only other approved opioid (morphine-like) narcotic painkiller (analgesic) for children is Duragesic (fentanyl), and both of these drugs can be and are abused — though OxyContin has been reformulated, and heroin is cheaper and easier to obtain.[72] The FDA has said OxyContin is permissible to prescribe and use specifically in children who have been on other opiate painkillers, and who can be judged to tolerate at least 20 milligrams (mg) of the OxyContin a day.[73]

Legal status

General

Oxycodone is subject to international conventions on narcotic drugs. In addition, oxycodone is subject to national laws that differ by country. The 1931 Convention for Limiting the Manufacture and Regulating the Distribution of Narcotic Drugs of the League of Nations included oxycodone.[74] The 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of the United Nations, which replaced the 1931 convention, categorized oxycodone in Schedule I.[75] Global restrictions on Schedule I drugs include "limit[ing] exclusively to medical and scientific purposes the production, manufacture, export, import, distribution of, trade in, use and possession of" these drugs; "requir[ing] medical prescriptions for the supply or dispensation of [these] drugs to individuals"; and "prevent[ing] the accumulation" of quantities of these drugs "in excess of those required for the normal conduct of business".[75]

Australia

Oxycodone is in Schedule I (derived from the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs) of the Commonwealth's Narcotic Drugs Act 1967.[76] In addition, it is in Schedule 8 of the Australian Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons ("Poisons Standard"), meaning it is a "controlled drug... which should be available for use but require[s] restriction of manufacture, supply, distribution, possession and use to reduce abuse, misuse and physical or psychological dependence".[77]

Canada

Oxycodone is a controlled substance under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA).[78]

Canada - Legislative changes

In February 2012, Ontario passed legislation to allow the expansion of an already existing drug-tracking system for publicly funded drugs to include those that are privately insured. This database will function to identify and monitor patient’s attempts to seek prescriptions from multiple doctors or retrieve from multiple pharmacies. Other provinces have proposed similar legislation, while some, such as Nova Scotia, have legislation already in effect for monitoring prescription drug use. These changes have coincided with other changes in Ontario’s legislation to target the misuse of painkillers and high addiction rates to drugs such as oxycodone. As of February 29, 2012, Ontario passed legislation delisting oxycodone from the province’s public drug benefit program. This was a first for any province to delist a drug based on addictive properties. The new law prohibits prescriptions for OxyNeo except to certain patients under the Exceptional Access Program including palliative care and in other extenuating circumstances. Patients already prescribed oxycodone will receive coverage for an additional year for OxyNeo, and after that, it will be disallowed unless designated under the exceptional access program.[79]

Much of the legislative activity has stemmed from Purdue Pharma’s decision in 2011 to begin a modification of oxycodone’s composition to make it more difficult to crush for snorting or injecting. The new formulation, OxyNeo, is intended to be preventative in this regard and retain its effectiveness as a pain killer. Since introducing its Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act, Ontario has committed to focusing on drug addiction, particularly in the monitoring and identification of problem opioid prescriptions, as well as the education of patients, doctors, and pharmacists.[80] This Act, introduced in 2010, commits to the establishment of a unified database to fulfil this intention.[81] Both the public and medical community have received the legislation positively, though concerns about the ramifications of legal changes have been expressed. Because laws are largely provincially regulated, many speculate a national strategy is needed to prevent smuggling across provincial borders from jurisdictions with looser restrictions.[82]

In 2015, Purdue Pharma's abuse-resistant OxyNEO and six generic versions of OxyContin had been on the Canada-wide approved list for prescriptions since 2012. In June 2015, then federal Minister of Health Rona Ambrose announced that within three years all oxycodone products sold in Canada would need to be tamper-resistant. Some experts warned that the generic product manufacturers may not have the technology to achieve that goal, possibly giving Purdue Pharma a monopoly on this opiate.[83]

Canada - Lawsuits

Several class action suits across Canada have been launched against the Purdue group of companies and affiliates. Claimants argue the pharmaceutical manufacturers did not meet a standard of care and were negligent in doing so. These lawsuits reference earlier judgments in the United States, which held that Purdue was liable for wrongful marketing practices and misbranding. Since 2007, the Purdue companies have paid over $650 million in settling litigation or facing criminal fines.[84]

Germany

The drug is in Appendix III of the Narcotics Act (Betäubungsmittelgesetz or BtMG).[85] The law allows only physicians, dentists, and veterinarians (Ärzte, Zahnärzte und Tierärzte) to prescribe oxycodone and the federal government to regulate the prescriptions (e.g., by requiring reporting).[85]

Hong Kong

Oxycodone is regulated under Part I of Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance.[86]

Japan

Oxycodone is a restricted drug in Japan. Its import / export is strictly restricted to specially designated organizations having prior permit to import it. In a high-profile case a top Toyota executive, who claimed to be unaware of the law, was arrested for importing Oxycodone into Japan.[87][88]

Singapore

Oxycodone is listed as a Class A drug in the Misuse of Drugs Act of Singapore, which means offences in relation to the drug attract the most severe level of punishment. A conviction for unauthorized manufacture of the drug attracts a minimum sentence of 10 years of imprisonment and corporal punishment of five strokes of the cane, and a maximum sentence of life imprisonment or 30 years of imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane.[89] The minimum and maximum penalties for unauthorized trafficking in the drug are respectively five years of imprisonment and five strokes of the cane, and 20 years of imprisonment and 15 strokes of the cane.[90]

United Kingdom

Oxycodone is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act.[91] For Class A drugs, which are "considered to be the most likely to cause harm", possession without a prescription is punishable by up to seven years in prison, an unlimited fine, or both.[92] Dealing of the drug illegally is punishable by up to life imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both.[92] In addition, oxycodone is a Schedule 2 drug per the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001 which "provide certain exemptions from the provisions of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971".[93]

United States

Under the Controlled Substances Act, enacted in 1971 by President Richard Nixon,[94] oxycodone is a Schedule II controlled substance whether by itself or part of a multi-ingredient medication. The DEA lists oxycodone both for sale and for use in manufacturing other opioids as ACSCN 9143 and in 2013 approved the following annual aggregate manufacturing quotas: 131.5 metric tons for sale, down from 153.75 in 2012, and 10.25 metric tons for conversion, unchanged from the previous year.[95] The salts in use are hydrochloride (free base conversion ratio .896), bitartrate (.667), tartrate (.750), camphosulphonate (.576), pectinate (.588), phenylpriopionate (.678), sulphate, (.887), phosphate (.763), and terephthalate (.792); the first and last are found together in Percodan and hydrochloride by itself is the basis of most American oxycodone products whilst bitartrate, tartrate, pectinate, and phosphate are also used alongside the other two in Europe. Methyiodide and hydroiodide are mentioned in older European publications.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kalso E (2005). "Oxycodone". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 29 (5S): S47–S56. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.010. PMID 15907646.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Roxicodone, OxyContin (oxycodone) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 O'Neil, Maryadele J., ed. (2006). The Merck index (14 ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co. ISBN 978-0-911910-00-1.

- ↑ German (DE) Patent 296916

- 1 2 3 Sneader W (2005). Drug discovery: a history. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. p. 119. ISBN 0-471-89980-1.

- ↑ "eMC". http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/searchresults.aspx?term=Oxycodone&searchtype=QuickSearch. eMC. Retrieved 1 July 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 "Oxycodone". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ Riley J, Eisenberg E, Müller-Schwefe G, Drewes AM, Arendt-Nielsen L (2008). "Oxycodone: a review of its use in the management of pain". Curr Med Res Opin 24 (1): 175–192. doi:10.1185/030079908X253708. PMID 18039433.

- ↑ Biancofiore G (September 2006). "Oxycodone controlled release in cancer pain management". Ther Clin Risk Manag 2 (3): 229–34. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2006.2.3.229. PMC 1936259. PMID 18360598.

- ↑ Biancofiore G (September 2006). "Oxycodone controlled release in cancer pain management.". Therapeutics and clinical risk management 2 (3): 229–34. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2006.2.3.229. PMC 1936259. PMID 18360598.

- ↑ Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, Hanna M, Kalso E, McQuay HJ, Mercadante S, Meynadier J, Poulain P, Ripamonti C, Radbruch L, Casas JR, Sawe J, Twycross RG, Ventafridda V (March 2001). "Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations". Br. J. Cancer 84 (5): 587–93. doi:10.1054/bjoc.2001.1680. PMC 2363790. PMID 11237376.

- ↑ Stoll, Andrew L. and Stephanie Rueter. "Treatment Augmentation With Opiates in Severe and Refractory Major Depression". www.opiods.com. American Journal of Psychiatry, Dec. 1999. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (2009-03-23). "Oxycodone". U.S. National Library of Medicine, MedlinePlus. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ↑ "Oxycodone Side Effects". Drugs.com. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 1. Package insert Oxycontin (PDF). Stamford, CT: Purdue Pharma L.P. 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ Simpson K, et al. (December 2008). "Fixed-ratio combination oxycodone/naloxone compared with oxycodone alone for the relief of opioid-induced constipation in moderate-to-severe noncancer pain". Curr Med Res Opin 24 (12): 3503–3512. doi:10.1185/03007990802584454. PMID 19032132. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ↑ "Oxycodone". Center for Substance Abuse Research. 2005-05-02. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ↑ Rao R, Desai NS (June 2002). "OxyContin and neonatal abstinence syndrome" (PDF). J Perinatol 22 (4): 324–5. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210744. PMID 12032797. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ↑ Brennan MJ (2013). "The effect of opioid therapy on endocrine function". The American Journal of Medicine 126 (3 Suppl 1): S12–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.12.001. PMID 23414717.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2011) Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 9th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, pp. 1259–1262.

- ↑ Ross FB, Smith MT (1997). "The intrinsic antinociceptive effects of oxycodone appear to be κ-opioid receptor mediated". Pain 73 (2): 151–157. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00093-6. PMID 9415500.

- ↑ Smith MT (2008). "Differences between and combinations of opioids re-visited". Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 21 (5): 596–601. doi:10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830a4c4a. PMID 18784485.

- ↑ Kalso E (2007). "How different is oxycodone from morphine?". Pain 132 (3): 227–228. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.027. PMID 17961923.

- ↑ Nozaki C, Saitoh A, Kamei J (2006). "Characterization of the antinociceptive effects of oxycodone in diabetic mice". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 535 (1–3): 145–151. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.002. PMID 16533506.

- ↑ Nozaki C, Kamei J (2007). "Involvement of mu1-opioid receptor on oxycodone-induced antinociception in diabetic mice". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 560 (2–3): 160–162. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.021. PMID 17292346.

- ↑ Chahl, L. Opioids- mechanism of action. Aust Prescr 1996, 19, 63.

- 1 2 3 Lalovic B, Kharasch E, Hoffer C, Risler L, Liu-Chen LY, Shen DD (2006). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral oxycodone in healthy human subjects: role of circulating active metabolites" (PDF). Clin Pharmacol Ther 79 (5): 461–479. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.009. PMID 16678548. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ↑ Moore KA, Ramcharitar V, Levine B, Fowler D (September 2003). "Tentative identification of novel oxycodone metabolites in human urine". J Anal Toxicol 27 (6): 346–52. doi:10.1093/jat/27.6.346. PMID 14516487.

- ↑ Ishida T, Oguri K, Yoshimura H (1979). "Isolation and identification of urinary metabolites of oxycodone in rabbits". Drug Metab. Dispos. 7 (3): 162–5. PMID 38087.

- ↑ Gasche Y, Daali Y, Fathi M, Chiappe A, Cottini S, Dayer P, Desmeules J (December 2004). "Codeine intoxication associated with ultrarapid CYP2D6 metabolism". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (27): 2827–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041888. PMID 15625333.

- ↑ Otton SV, Wu D, Joffe RT, Cheung SW, Sellers EM (April 1993). "Inhibition by fluoxetine of cytochrome P450 2D6 activity". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 53 (4): 401–9. doi:10.1038/clpt.1993.43. PMID 8477556.

- ↑ Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic Guidelines: Analgesic. Version 4. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2007.

- ↑ Levy, Enno Freye; in collaboration with Joseph Victor (2007). Opioids in medicine a comprehensive review on the mode of action and the use of analgesics in different clinical pain states. New York: Springer Science+Business Media B.V. p. 371. ISBN 1402059477.

- 1 2 3 4 Eddy NB (1973). The National Research Council involvement in the opiate problem, 1928–1971. Washington: National Academy of Sciences.

- 1 2 3 May EL, Jacobson AE (1989). "The Committee on Problems of Drug Dependence: a legacy of the National Academy of Sciences. A historical account". Drug Alcohol Depend 23 (3): 183–218. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(89)90083-5. PMID 2666074.

- 1 2 Sunshine A, Olson NZ, Colon A, Rivera J, Kaiko RF, Fitzmartin RD, Reder RF, Goldenheim PD (July 1996). "Analgesic efficacy of controlled-release oxycodone in postoperative pain". J Clin Pharmacol 36 (7): 595–603. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04223.x. PMID 8844441.

- ↑ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2005). "International convention against doping in sport" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ Hicks RW, Becker SC, Cousins DD, eds. (2008). MEDMARX data report. A report on the relationship of drug names and medication errors in response to the Institute of Medicine’s call for action (PDF). Rockville, MD: Center for the Advancement of Patient Safety, US Pharmacopeia. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ “Why do pollinators become 'sluggish'? Nectar chemical constituents from Epipactis helleborine L. Crantz Orchidaceae”. Applied Ecology & Environmental Research. 2005;3(2):29-38. Jakubska A, Przado D, Steininger M, Aniol-Kwiatkowska A, Kadej M.

- ↑ Oxycodone. Cesar.umd.edu. Retrieved on 2014-06-15.

- ↑ Generic OxyContin Availability. Drugs.com. Retrieved on 2014-06-15.

- 1 2 3 International Narcotics Control Board (2009). Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2009; statistics for 2007. Report E/INCB/2008/2 (PDF). New York: United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-048124-3.

- ↑ "Availability of Opioid Analgesics in the World and Asia, With a special focus on: Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand" (PDF). University of Wisconsin Pain & Policy Studies Group/World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Center for Policy and Communications in Cancer Care. United Nations. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Narcotic Drugs: Estimated World Requirements for 2012 and Statistics for 2010. International Narcotics Control Board (2011).

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/pain-management/features/oxycontin-pain-relief-vs-abuse

- ↑ http://newlifehouse.com/top-10-commonly-abused-prescription-medications/

- ↑ Staff (2010). "New Abuse Deterrent Formulation Technology for Immediate-Release Opiods" (PDF). Grünenthal Group. Grünenthal Group Worldwide. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ Diep, Francie (May 13, 2013). "How Do You Make a Painkiller Addiction-Proof". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation.

- ↑ Coplan, Paul (2012). Findings from Purdue’s Post-Marketing Epidemiology Studies of Reformulated OxyContin’s Effects (PDF). NASCSA 2012 Conference. Scottsdale, Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2013.

- ↑ "Press Announcements > FDA approves abuse-deterrent labeling for reformulated OxyContin:". US Government – FDA. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ no byline.-->. "Pfizer and Acura Announce FDA Approval of Oxectatm (Oxycodone HCL, USP) CII". Pfizer News and Media. Pfizer Inc. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ Fiore, Kristina (June 20, 2011). "FDA Okays New Abuse-Resistant Opioid". MedPage Today. MedPage Today. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ Black E (2008). Australian drug trends 2007. Findings from the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS) (PDF). Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of New South Wales. ISBN 978-0-7334-2625-4.

- ↑ Boyle, Theresa (7 July 2014), "Opioid deaths soaring, study finds Opioid-related deaths in Ontario jumped by a whopping 242 per cent over two decades, according to a study by ICES and St. Mike's", The Star (Toronto, Ontario), retrieved 23 January 2015

- ↑ Donovan, Kevin (10 February 2009), "Oxycodone found to be more deadly than heroin", The Star (Toronto, Ontario), retrieved 23 January 2015

- ↑ "Study finds huge rise in oxycodone deaths". CTV News. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- 1 2 OxyContin Fact Sheet. (PDF). ccsa.ca. Retrieved on 2012-05-10.

- ↑ Health Canada – Misuse and Abuse of Oxycodone-based Prescription Drugs. Hc-sc.gc.ca (2010-01-11). Retrieved on 2012-05-10.

- ↑ Kirkey, Sharon (May 23, 2012). "OxyNEO another prescription for disaster?". Globe and Mail (Toronto, Ontario).

- ↑ Criger, Erin (August 17, 2015). "Death of OxyContin behind rise of fentanyl?". CityNews. Rogers Digital Media.

- ↑ Gatehouse, Jonathon; Macdonald, Nancy (June 22, 2015). Macleans. Rogers Media http://www.macleans.ca/society/health/fentanyl-the-king-of-all-opiates-and-a-killer-drug-crisis/. Retrieved December 15, 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Southwick, Reid (December 2, 2015). "Fentanyl brings tragedy to Blood Tribe". Calgary Herald (Calgary, Alberta). Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ↑ Police believe organized crime is flooding the Blood Tribe reserve with an illegal drug that has been linked to 10 deaths, Alberta, 23 January 2015, retrieved 23 January 2015

- ↑ Gordon T (2008-03-30). "Scots' use of 'hillbilly heroin' rises by 430%". Sunday Times (London).

- ↑ Thompson T (2002-03-24). "Epidemic fear as 'hillbilly heroin' hits the streets". Society Guardian. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- 1 2 Girioin, Lisa; Haely, Melissa (11 September 2013). "FDA to require stricter labeling for pain drugs". Los Angeles Times. pp. A1 and A9.

- ↑ "Drug Overdose in the United States: Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "ER/LA Opioid Analgesic Class Labeling Changes and Postmarket Requirements" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Now a counselor, she went from stoned to straight, San Francisco Chronicle, November 2. 2015.

- ↑ Street Names and Nicknames for OxyContin

- ↑ Policy Impact: Prescription Pain Killer Overdoses Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ↑ Reformulated OxyContin reduces abuse but many addicts have switched to heroin, The Pharmaceutical Journal, 16 March 2015.

- ↑ http://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/fda-approves-oxycontin-for-kids-11-to-16/ar-BBlK3zS?ocid=spartandhp

- ↑ League of Nations (1931). "Convention for limiting the manufacture and regulating the distribution of narcotic drugs" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- 1 2 "United Nations conference for the adoption of a single convention on narcotic drugs. Final act" (PDF). 1961. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ↑ Commonwealth of Australia. "Narcotic Drugs Act 1967 – first schedule". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Australian Government. Department of Health and Aging. Therapeutic Goods Administration (June 2008). Standard for the uniform scheduling of drugs and poisons no. 23 (PDF). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 1-74186-596-4. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Canada Department of Justice (2009-02-27). "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (1996, c. 19)". Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ Olgilvie, Megan. "Ontario delisting OxyContin and its substitute from drug benefit program" Toronto Star (2012-02-17)

- ↑ Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act. 2010. Ministry of Health and Long Term Care.

- ↑ Dhalla, Irfan and Born, Karen (2012-02-22) Opioids. healthydebate.ca Archived March 21, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ontario OxyContin Rules: New Restrictions Applauded But National Rules Needed. Huffington Post. Canadian Press (2012-02-20)

- ↑ Weeks, Carly; Howlett, Karen (August 4, 2015). author=no byline "New oxycodone rules would give drug maker a monopoly in Canada, experts warn" Check

|url= - ↑ Martin, Kevin. Lawsuit attacks OxyContin use. C-Health. Sun Media (2008-08-08)

- 1 2 German Federal Ministry of Justice (2009-01-19). "Act on the circulation of narcotics (Narcotics Act – BtMG)" (in German). Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ↑ Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, People's Republic of China. "Dangerous drugs ordinance – chapter 134". Hong Kong Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ Toyota's American PR chief arrested for suspected drug violation

- ↑ Toyota: American exec did not intend to break Japan law

- ↑ Misuse of Drugs Act (Cap. 185, 2008 Rev. Ed.) (Singapore), section 6(1).

- ↑ Misuse of Drugs Act (Singapore), section 5(1).

- ↑ "List of drugs currently controlled under the Misuse of Drugs legislation" (PDF). UK. Home Office. 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- 1 2 "Class A, B and C drugs". UK. Home Office. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ "Statutory instrument 2001 No. 3998. The Misuse of Drugs regulations 2001". UK. Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ DEA. "Controlled substance scheduling". Drug information and scheduling. Drug Enforcerment Administration. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ "DEA Diversion Control CSA". US Dept of Justice – DEA. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

External links

- Coluzzi F, Mattia C. Oxycodone. Pharmacological profile and clinical data in chronic pain management. Minerva Anestesiol 2005 Jul–Aug;71(7–8):451-60.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||