Relay

A relay is an electrically operated switch. Many relays use an electromagnet to mechanically operate a switch, but other operating principles are also used, such as solid-state relays. Relays are used where it is necessary to control a circuit by a low-power signal (with complete electrical isolation between control and controlled circuits), or where several circuits must be controlled by one signal. The first relays were used in long distance telegraph circuits as amplifiers: they repeated the signal coming in from one circuit and re-transmitted it on another circuit. Relays were used extensively in telephone exchanges and early computers to perform logical operations.

A type of relay that can handle the high power required to directly control an electric motor or other loads is called a contactor. Solid-state relays control power circuits with no moving parts, instead using a semiconductor device to perform switching. Relays with calibrated operating characteristics and sometimes multiple operating coils are used to protect electrical circuits from overload or faults; in modern electric power systems these functions are performed by digital instruments still called "protective relays".

History

The American scientist Joseph Henry is often claimed to have invented a relay in 1835 in order to improve his version of the electrical telegraph, developed earlier in 1831.[1][2][3][4] However, there is little in the way of official documentation to suggest he had made the discovery prior to 1837.[5]

It is claimed that the English inventor Edward Davy "certainly invented the electric relay"[6] in his electric telegraph c.1835.

A simple device, which we now call a relay, was included in the original 1840 telegraph patent[7] of Samuel Morse. The mechanism described acted as a digital amplifier, repeating the telegraph signal, and thus allowing signals to be propagated as far as desired. This overcame the problem of limited range of earlier telegraphy schemes.

The word relay appears in the context of electromagnetic operations from 1860.[8]

Basic design and operation

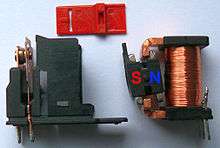

A simple electromagnetic relay consists of a coil of wire wrapped around a soft iron core, an iron yoke which provides a low reluctance path for magnetic flux, a movable iron armature, and one or more sets of contacts (there are two in the relay pictured). The armature is hinged to the yoke and mechanically linked to one or more sets of moving contacts. It is held in place by a spring so that when the relay is de-energized there is an air gap in the magnetic circuit. In this condition, one of the two sets of contacts in the relay pictured is closed, and the other set is open. Other relays may have more or fewer sets of contacts depending on their function. The relay in the picture also has a wire connecting the armature to the yoke. This ensures continuity of the circuit between the moving contacts on the armature, and the circuit track on the printed circuit board (PCB) via the yoke, which is soldered to the PCB.

When an electric current is passed through the coil it generates a magnetic field that activates the armature, and the consequent movement of the movable contact(s) either makes or breaks (depending upon construction) a connection with a fixed contact. If the set of contacts was closed when the relay was de-energized, then the movement opens the contacts and breaks the connection, and vice versa if the contacts were open. When the current to the coil is switched off, the armature is returned by a force, approximately half as strong as the magnetic force, to its relaxed position. Usually this force is provided by a spring, but gravity is also used commonly in industrial motor starters. Most relays are manufactured to operate quickly. In a low-voltage application this reduces noise; in a high voltage or current application it reduces arcing.

When the coil is energized with direct current, a diode is often placed across the coil to dissipate the energy from the collapsing magnetic field at deactivation, which would otherwise generate a voltage spike dangerous to semiconductor circuit components. Such diodes were not widely used before the application of transistors as relay drivers, but soon became ubiquitous as early germanium transistors were easily destroyed by this surge. Some automotive relays include a diode inside the relay case.

If the relay is driving a large, or especially a reactive load, there may be a similar problem of surge currents around the relay output contacts. In this case a snubber circuit (a capacitor and resistor in series) across the contacts may absorb the surge. Suitably rated capacitors and the associated resistor are sold as a single packaged component for this commonplace use.

If the coil is designed to be energized with alternating current (AC), some method is used to split the flux into two out-of-phase components which add together, increasing the minimum pull on the armature during the AC cycle. Typically this is done with a small copper "shading ring" crimped around a portion of the core that creates the delayed, out-of-phase component,[9] which holds the contacts during the zero crossings of the control voltage.

Types

Latching relay

A latching relay (also called "impulse", "keep", or "stay" relays) maintains either contact position indefinitely without power applied to the coil. The advantage is that one coil consumes power only for an instant while the relay is being switched, and the relay contacts retain this setting across a power outage. A latching relay allows remote control of building lighting without the hum that may be produced from a continuously (AC) energized coil.

In one mechanism, two opposing coils with an over-center spring or permanent magnet hold the contacts in position after the coil is de-energized. A pulse to one coil turns the relay on and a pulse to the opposite coil turns the relay off. This type is widely used where control is from simple switches or single-ended outputs of a control system, and such relays are found in avionics and numerous industrial applications.

Another latching type has a remanent core that retains the contacts in the operated position by the remanent magnetism in the core. This type requires a current pulse of opposite polarity to release the contacts. A variation uses a permanent magnet that produces part of the force required to close the contact; the coil supplies sufficient force to move the contact open or closed by aiding or opposing the field of the permanent magnet.[10] A polarity controlled relay needs changeover switches or an H bridge drive circuit to control it. The relay may be less expensive than other types, but this is partly offset by the increased costs in the external circuit.

In another type, a ratchet relay has a ratchet mechanism that holds the contacts closed after the coil is momentarily energized. A second impulse, in the same or a separate coil, releases the contacts.[10] This type may be found in certain cars, for headlamp dipping and other functions where alternating operation on each switch actuation is needed.

A stepping relay is a specialized kind of multi-way latching relay designed for early automatic telephone exchanges.

An earth leakage circuit breaker includes a specialized latching relay.

Very early computers often stored bits in a magnetically latching relay, such as ferreed or the later memreed in the 1ESS switch.

Some early computers used ordinary relays as a kind of latch—they store bits in ordinary wire spring relays or reed relays by feeding an output wire back as an input, resulting in a feedback loop or sequential circuit. Such an electrically latching relay requires continuous power to maintain state, unlike magnetically latching relays or mechanically racheting relays.

In computer memories, latching relays and other relays were replaced by delay line memory, which in turn was replaced by a series of ever-faster and ever-smaller memory technologies.

Reed relay

A reed relay is a reed switch enclosed in a solenoid. The switch has a set of contacts inside an evacuated or inert gas-filled glass tube which protects the contacts against atmospheric corrosion; the contacts are made of magnetic material that makes them move under the influence of the field of the enclosing solenoid or an external magnet.

Reed relays can switch faster than larger relays and require very little power from the control circuit. However, they have relatively low switching current and voltage ratings. Though rare, the reeds can become magnetized over time, which makes them stick 'on' even when no current is present; changing the orientation of the reeds with respect to the solenoid's magnetic field can resolve this problem.

Sealed contacts with mercury-wetted contacts have longer operating lives and less contact chatter than any other kind of relay.[11]

Mercury-wetted relay

A mercury-wetted reed relay is a form of reed relay in which the contacts are wetted with mercury. Such relays are used to switch low-voltage signals (one volt or less) where the mercury reduces the contact resistance and associated voltage drop, for low-current signals where surface contamination may make for a poor contact, or for high-speed applications where the mercury eliminates contact bounce. Mercury wetted relays are position-sensitive and must be mounted vertically to work properly. Because of the toxicity and expense of liquid mercury, these relays are now rarely used.

The mercury-wetted relay has one particular advantage, in that the contact closure appears to be virtually instantaneous, as the mercury globules on each contact coalesce. The current rise time through the contacts is generally considered to be a few picoseconds, however in a practical circuit it will be limited by the inductance of the contacts and wiring. It was quite common, before the restrictions on the use of mercury, to use a mercury-wetted relay in the laboratory as a convenient means of generating fast rise time pulses, however although the rise time may be picoseconds, the exact timing of the event is, like all other types of relay, subject to considerable jitter, possibly milliseconds, due to mechanical imperfections.

The same coalescence process causes another effect, which is a nuisance in some applications. The contact resistance is not stable immediately after contact closure, and drifts, mostly downwards, for several seconds after closure, the change perhaps being 0.5 ohm.

Mercury relay

A mercury relay is a relay that uses mercury as the switching element. They are used where contact erosion would be a problem for conventional relay contacts. Owing to environmental considerations about significant amount of mercury used and modern alternatives, they are now comparatively uncommon.

Polarized relay

A polarized relay places the armature between the poles of a permanent magnet to increase sensitivity. Polarized relays were used in middle 20th Century telephone exchanges to detect faint pulses and correct telegraphic distortion. The poles were on screws, so a technician could first adjust them for maximum sensitivity and then apply a bias spring to set the critical current that would operate the relay.

Machine tool relay

A machine tool relay is a type standardized for industrial control of machine tools, transfer machines, and other sequential control. They are characterized by a large number of contacts (sometimes extendable in the field) which are easily converted from normally open to normally closed status, easily replaceable coils, and a form factor that allows compactly installing many relays in a control panel. Although such relays once were the backbone of automation in such industries as automobile assembly, the programmable logic controller (PLC) mostly displaced the machine tool relay from sequential control applications.

A relay allows circuits to be switched by electrical equipment: for example, a timer circuit with a relay could switch power at a preset time. For many years relays were the standard method of controlling industrial electronic systems. A number of relays could be used together to carry out complex functions (relay logic). The principle of relay logic is based on relays which energize and de-energize associated contacts. Relay logic is the predecessor of ladder logic, which is commonly used in programmable logic controllers.

Coaxial relay

Where radio transmitters and receivers share one antenna, often a coaxial relay is used as a TR (transmit-receive) relay, which switches the antenna from the receiver to the transmitter. This protects the receiver from the high power of the transmitter. Such relays are often used in transceivers which combine transmitter and receiver in one unit. The relay contacts are designed not to reflect any radio frequency power back toward the source, and to provide very high isolation between receiver and transmitter terminals. The characteristic impedance of the relay is matched to the transmission line impedance of the system, for example, 50 ohms.[12]

Time delay relay

Timing relays are arranged for an intentional delay in operating their contacts. A very short (a fraction of a second) delay would use a copper disk between the armature and moving blade assembly. Current flowing in the disk maintains magnetic field for a short time, lengthening release time. For a slightly longer (up to a minute) delay, a dashpot is used. A dashpot is a piston filled with fluid that is allowed to escape slowly; both air-filled and oil-filled dashpots are used. The time period can be varied by increasing or decreasing the flow rate. For longer time periods, a mechanical clockwork timer is installed. Relays may be arranged for a fixed timing period, or may be field adjustable, or remotely set from a control panel. Modern microprocessor-based timing relays provide precision timing over a great range.

Some relays are constructed with a kind of "shock absorber" mechanism attached to the armature which prevents immediate, full motion when the coil is either energized or de-energized. This addition gives the relay the property of time-delay actuation. Time-delay relays can be constructed to delay armature motion on coil energization, de-energization, or both.

Time-delay relay contacts must be specified not only as either normally open or normally closed, but whether the delay operates in the direction of closing or in the direction of opening. The following is a description of the four basic types of time-delay relay contacts.

First we have the normally open, timed-closed (NOTC) contact. This type of contact is normally open when the coil is unpowered (de-energized). The contact is closed by the application of power to the relay coil, but only after the coil has been continuously powered for the specified amount of time. In other words, the direction of the contact's motion (either to close or to open) is identical to a regular NO contact, but there is a delay in closing direction. Because the delay occurs in the direction of coil energization, this type of contact is alternatively known as a normally open, on-delay:

Contactor

A contactor is a heavy-duty relay used for switching electric motors and lighting loads, but contactors are not generally called relays. Continuous current ratings for common contactors range from 10 amps to several hundred amps. High-current contacts are made with alloys containing silver. The unavoidable arcing causes the contacts to oxidize; however, silver oxide is still a good conductor.[13] Contactors with overload protection devices are often used to start motors. Contactors can make loud sounds when they operate, so they may be unfit for use where noise is a chief concern.

A contactor is an electrically controlled switch used for switching a power circuit, similar to a relay except with higher current ratings.[14] A contactor is controlled by a circuit which has a much lower power level than the switched circuit.

Contactors come in many forms with varying capacities and features. Unlike a circuit breaker, a contactor is not intended to interrupt a short circuit current. Contactors range from those having a breaking current of several amperes to thousands of amperes and 24 V DC to many kilovolts. The physical size of contactors ranges from a device small enough to pick up with one hand, to large devices approximately a meter (yard) on a side.

Solid-state relay

A solid state relay or SSR is a solid state electronic component that provides a function similar to an electromechanical relay but does not have any moving components, increasing long-term reliability. A solid-state relay uses a thyristor, TRIAC or other solid-state switching device, activated by the control signal, to switch the controlled load, instead of a solenoid. An optocoupler (a light-emitting diode (LED) coupled with a photo transistor) can be used to isolate control and controlled circuits.

As every solid-state device has a small voltage drop across it, this voltage drop limits the amount of current a given SSR can handle. The minimum voltage drop for such a relay is a function of the material used to make the device. Solid-state relays rated to handle as much as 1,200 amperes have become commercially available. Compared to electromagnetic relays, they may be falsely triggered by transients and in general may be susceptible to damage by extreme cosmic ray and EMP episodes.

Solid state contactor relay

A solid state contactor is a heavy-duty solid state relay, including the necessary heat sink, used where frequent on/off cycles are required, such as with electric heaters, small electric motors, and lighting loads. There are no moving parts to wear out and there is no contact bounce due to vibration. They are activated by AC control signals or DC control signals from Programmable logic controller (PLCs), PCs, Transistor-transistor logic (TTL) sources, or other microprocessor and microcontroller controls.

Buchholz relay

A Buchholz relay is a safety device sensing the accumulation of gas in large oil-filled transformers, which will alarm on slow accumulation of gas or shut down the transformer if gas is produced rapidly in the transformer oil. The contacts are not operated by an electric current but by the pressure of accumulated gas or oil flow.

Force-guided contacts relay

A 'force-guided contacts relay' has relay contacts that are mechanically linked together, so that when the relay coil is energized or de-energized, all of the linked contacts move together. If one set of contacts in the relay becomes immobilized, no other contact of the same relay will be able to move. The function of force-guided contacts is to enable the safety circuit to check the status of the relay. Force-guided contacts are also known as "positive-guided contacts", "captive contacts", "locked contacts", "mechanically linked contacts", or "safety relays".

These safety relays have to follow design rules and manufacturing rules that are defined in one main machinery standard EN 50205 : Relays with forcibly guided (mechanically linked) contacts. These rules for the safety design are the one that are defined in type B standards such as EN 13849-2 as Basic safety principles and Well-tried safety principles for machinery that applies to all machines.

Force-guided contacts by themselves can not guarantee that all contacts are in the same state, however they do guarantee, subject to no gross mechanical fault, that no contacts are in opposite states. Otherwise, a relay with several normally open (NO) contacts may stick when energised, with some contacts closed and others still slightly open, due to mechanical tolerances. Similarly, a relay with several normally closed (NC) contacts may stick to the unenergised position, so that when energised, the circuit through one set of contacts is broken, with a marginal gap, while the other remains closed. By introducing both NO and NC contacts, or more commonly, changeover contacts, on the same relay, it then becomes possible to guarantee that if any NC contact is closed, all NO contacts are open, and conversely, if any NO contact is closed, all NC contacts are open. It is not possible to reliably ensure that any particular contact is closed, except by potentially intrusive and safety-degrading sensing of its circuit conditions, however in safety systems it is usually the NO state that is most important, and as explained above, this is reliably verifiable by detecting the closure of a contact of opposite sense.

Force-guided contact relays are made with different main contact sets, either NO, NC or changeover, and one or more auxiliary contact sets, often of reduced current or voltage rating, used for the monitoring system. Contacts may be all NO, all NC, changeover, or a mixture of these, for the monitoring contacts, so that the safety system designer can select the correct configuration for the particular application. Safety relays are used as part of an engineered safety system.

Overload protection relay

Electric motors need overcurrent protection to prevent damage from over-loading the motor, or to protect against short circuits in connecting cables or internal faults in the motor windings.[15] The overload sensing devices are a form of heat operated relay where a coil heats a bimetallic strip, or where a solder pot melts, releasing a spring to operate auxiliary contacts. These auxiliary contacts are in series with the coil. If the overload senses excess current in the load, the coil is de-energized.

This thermal protection operates relatively slowly allowing the motor to draw higher starting currents before the protection relay will trip. Where the overload relay is exposed to the same environment as the motor, a useful though crude compensation for motor ambient temperature is provided.

The other common overload protection system uses an electromagnet coil in series with the motor circuit that directly operates contacts. This is similar to a control relay but requires a rather high fault current to operate the contacts. To prevent short over current spikes from causing nuisance triggering the armature movement is damped with a dashpot. The thermal and magnetic overload detections are typically used together in a motor protection relay.

Electronic overload protection relays measure motor current and can estimate motor winding temperature using a "thermal model" of the motor armature system that can be set to provide more accurate motor protection. Some motor protection relays include temperature detector inputs for direct measurement from a thermocouple or resistance thermometer sensor embedded in the winding.

Vacuum relays

A sensitive relay having its contacts mounted in a highly evacuated glass housing, to permit handling radio-frequency voltages as high as 20,000 volts without flashover between contacts even though contact spacing is but a few hundredths of an inch when open.

Safety relays

Safety relays are devices which generally implement safety functions. In the event of a hazard, the task of such a safety function is to use appropriate measures to reduce the existing risk to an acceptable level.[16]

Multivoltage relays

Multivoltage relays are devices designed to work for wide voltage ranges such as 24 to 240 VAC/VDC and wide frequency ranges such as 0 to 300 Hz. They are indicated for use in installations that do not have stable supply voltages.

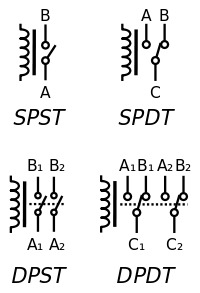

Pole and throw

Since relays are switches, the terminology applied to switches is also applied to relays; a relay switches one or more poles, each of whose contacts can be thrown by energizing the coil.

Normally open (NO) contacts connect the circuit when the relay is activated; the circuit is disconnected when the relay is inactive. It is also called a "Form A" contact or "make" contact. NO contacts may also be distinguished as "early-make" or "NOEM", which means that the contacts close before the button or switch is fully engaged.

Normally closed (NC) contacts disconnect the circuit when the relay is activated; the circuit is connected when the relay is inactive. It is also called a "Form B" contact or "break" contact. NC contacts may also be distinguished as "late-break" or "NCLB", which means that the contacts stay closed until the button or switch is fully disengaged.

Change-over (CO), or double-throw (DT), contacts control two circuits: one normally open contact and one normally closed contact with a common terminal. It is also called a "Form C" contact or "transfer" contact ("break before make"). If this type of contact has a "make before break" action, then it is called a "Form D" contact.

The following designations are commonly encountered:

- SPST – Single Pole Single Throw. These have two terminals which can be connected or disconnected. Including two for the coil, such a relay has four terminals in total. It is ambiguous whether the pole is normally open or normally closed. The terminology "SPNO" and "SPNC" is sometimes used to resolve the ambiguity.

- SPDT – Single Pole Double Throw. A common terminal connects to either of two others. Including two for the coil, such a relay has five terminals in total.

- DPST – Double Pole Single Throw. These have two pairs of terminals. Equivalent to two SPST switches or relays actuated by a single coil. Including two for the coil, such a relay has six terminals in total. The poles may be Form A or Form B (or one of each).

- DPDT – Double Pole Double Throw. These have two rows of change-over terminals. Equivalent to two SPDT switches or relays actuated by a single coil. Such a relay has eight terminals, including the coil.

The "S" or "D" may be replaced with a number, indicating multiple switches connected to a single actuator. For example, 4PDT indicates a four pole double throw relay that has 12 switch terminals.

EN 50005 are among applicable standards for relay terminal numbering; a typical EN 50005-compliant SPDT relay's terminals would be numbered 11, 12, 14, A1 and A2 for the C, NC, NO, and coil connections, respectively.[17]

DIN 72552 defines contact numbers in relays for automotive use;

- 85 = relay coil -

- 86 = relay coil +

- 87 = common contact

- 87a = normally closed contact

- 87b = normally open contact

Applications

Relays are used wherever it is necessary to control a high power or high voltage circuit with a low power circuit, especially when galvanic isolation is desirable. The first application of relays was in long telegraph lines, where the weak signal received at an intermediate station could control a contact, regenerating the signal for further transmission. High-voltage or high-current devices can be controlled with small, low voltage wiring and pilots switches. Operators can be isolated from the high voltage circuit. Low power devices such as microprocessors can drive relays to control electrical loads beyond their direct drive capability. In an automobile, a starter relay allows the high current of the cranking motor to be controlled with small wiring and contacts in the ignition key.

Electromechanical switching systems including Strowger and Crossbar telephone exchanges made extensive use of relays in ancillary control circuits. The Relay Automatic Telephone Company also manufactured telephone exchanges based solely on relay switching techniques designed by Gotthilf Ansgarius Betulander. The first public relay based telephone exchange in the UK was installed in Fleetwood on 15 July 1922 and remained in service until 1959.[18][19]

The use of relays for the logical control of complex switching systems like telephone exchanges was studied by Claude Shannon, who formalized the application of Boolean algebra to relay circuit design in A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits. Relays can perform the basic operations of Boolean combinatorial logic. For example, the boolean AND function is realised by connecting normally open relay contacts in series, the OR function by connecting normally open contacts in parallel. Inversion of a logical input can be done with a normally closed contact. Relays were used for control of automated systems for machine tools and production lines. The Ladder programming language is often used for designing relay logic networks.

Early electro-mechanical computers such as the ARRA, Harvard Mark II, Zuse Z2, and Zuse Z3 used relays for logic and working registers. However, electronic devices proved faster and easier to use.

Because relays are much more resistant than semiconductors to nuclear radiation, they are widely used in safety-critical logic, such as the control panels of radioactive waste-handling machinery. Electromechanical protective relays are used to detect overload and other faults on electrical lines by opening and closing circuit breakers.

Relay application considerations

Selection of an appropriate relay for a particular application requires evaluation of many different factors:

- Number and type of contacts – normally open, normally closed, (double-throw)

- Contact sequence – "Make before Break" or "Break before Make". For example, the old style telephone exchanges required Make-before-break so that the connection didn't get dropped while dialing the number.

- Contact current rating – small relays switch a few amperes, large contactors are rated for up to 3000 amperes, alternating or direct current

- Contact voltage rating – typical control relays rated 300 VAC or 600 VAC, automotive types to 50 VDC, special high-voltage relays to about 15,000 V

- Operating lifetime, useful life - the number of times the relay can be expected to operate reliably. There is both a mechanical life and a contact life. The contact life is affected by the type of load switched. Breaking load current causes undesired arcing between the contacts, eventually leading to contacts that weld shut or contacts that fail due erosion by the arc.[20]

- Coil voltage – machine-tool relays usually 24 VDC, 120 or 250 VAC, relays for switchgear may have 125 V or 250 VDC coils,

- Coil current - Minimum current required for reliable operation and minimum holding current, as well as, effects of power dissipation on coil temperature, at various duty cycles. "Sensitive" relays operate on a few milliamperes

- Package/enclosure – open, touch-safe, double-voltage for isolation between circuits, explosion proof, outdoor, oil and splash resistant, washable for printed circuit board assembly

- Operating environment - minimum and maximum operating temperature and other environmental considerations such as effects of humidity and salt

- Assembly – Some relays feature a sticker that keeps the enclosure sealed to allow PCB post soldering cleaning, which is removed once assembly is complete.

- Mounting – sockets, plug board, rail mount, panel mount, through-panel mount, enclosure for mounting on walls or equipment

- Switching time – where high speed is required

- "Dry" contacts – when switching very low level signals, special contact materials may be needed such as gold-plated contacts

- Contact protection – suppress arcing in very inductive circuits

- Coil protection – suppress the surge voltage produced when switching the coil current

- Isolation between coil contacts

- Aerospace or radiation-resistant testing, special quality assurance

- Expected mechanical loads due to acceleration – some relays used in aerospace applications are designed to function in shock loads of 50 g or more

- Size - smaller relays often resist mechanical vibration and shock better than larger relays, because of the lower inertia of the moving parts and the higher natural frequencies of smaller parts.[11] Larger relays often handle higher voltage and current than smaller relays.

- Accessories such as timers, auxiliary contacts, pilot lamps, and test buttons

- Regulatory approvals

- Stray magnetic linkage between coils of adjacent relays on a printed circuit board.

There are many considerations involved in the correct selection of a control relay for a particular application. These considerations include factors such as speed of operation, sensitivity, and hysteresis. Although typical control relays operate in the 5 ms to 20 ms range, relays with switching speeds as fast as 100 us are available. Reed relays which are actuated by low currents and switch fast are suitable for controlling small currents.

As with any switch, the contact current (unrelated to the coil current) must not exceed a given value to avoid damage. In high-inductance circuits such as motors, other issues must be addressed. When an inductance is connected to a power source, an input surge current or electromotor starting current larger than the steady-state current exists. When the circuit is broken, the current cannot change instantaneously, which creates a potentially damaging arc across the separating contacts.

Consequently, for relays used to control inductive loads, we must specify the maximum current that may flow through the relay contacts when it actuates, the make rating; the continuous rating; and the break rating. The make rating may be several times larger than the continuous rating, which is itself larger than the break rating.

Derating factors

| Type of load | % of rated value |

|---|---|

| Resistive | 75 |

| Inductive | 35 |

| Motor | 20 |

| Filament | 10 |

| Capacitive | 75 |

Control relays should not be operated above rated temperature because of resulting increased degradation and fatigue. Common practice is to derate 20 degrees Celsius from the maximum rated temperature limit. Relays operating at rated load are affected by their environment. Oil vapor may greatly decrease the contact life, and dust or dirt may cause the contacts to burn before the end of normal operating life. Control relay life cycle varies from 50,000 to over one million cycles depending on the electrical loads on the contacts, duty cycle, application, and the extent to which the relay is derated. When a control relay is operating at its derated value, it is controlling a smaller value of current than its maximum make and break ratings. This is often done to extend the operating life of a control relay. The table lists the relay derating factors for typical industrial control applications.

Undesired arcing

Switching while "wet" (under load) causes undesired arcing between the contacts, eventually leading to contacts that weld shut or contacts that fail due to a buildup of contact surface damage caused by the destructive arc energy.[20]

Inside the 1ESS switch matrix switch and certain other high-reliability designs, the reed switches are always switched "dry" to avoid that problem, leading to much longer contact life.[21]

Without adequate contact protection, the occurrence of electric current arcing causes significant degradation of the contacts, which suffer significant and visible damage. Every time a relay transitions either from a closed to an open state (break arc) or from an open to a closed state (make arc & bounce arc), under load, an electrical arc can occur between the two contact points (electrodes) of the relay. In many situations, the break arc is more energetic and thus more destructive, in particular with resistive-type loads. However, inductive loads can cause more destructive make arcs. For example, with standard electric motors, the start-up (inrush) current tends to be much greater than the running current. This translates into enormous make arcs.

During an arc event, the heat energy contained in the electrical arc is very high (tens of thousands of degrees Fahrenheit), causing the metal on the contact surfaces to melt, pool and migrate with the current. The extremely high temperature of the arc cracks the surrounding gas molecules creating ozone, carbon monoxide, and other compounds. The arc energy slowly destroys the contact metal, causing some material to escape into the air as fine particulate matter. This action causes the material in the contacts to degrade quickly, resulting in device failure. This contact degradation drastically limits the overall life of a relay to a range of about 10,000 to 100,000 operations, a level far below the mechanical life of the same device, which can be in excess of 20 million operations.[22]

Protective relays

For protection of electrical apparatus and transmission lines, electromechanical relays with accurate operating characteristics were used to detect overload, short-circuits, and other faults. While many such relays remain in use, digital devices now provide equivalent protective functions.

Railway signalling

Railway signalling relays are large considering the mostly small voltages (less than 120 V) and currents (perhaps 100 mA) that they switch. Contacts are widely spaced to prevent flashovers and short circuits over a lifetime that may exceed fifty years. BR930 series plug-in relays[23] are widely used on railways following British practice. These are 120 mm high, 180 mm deep and 56 mm wide and weigh about 1400 g, and can have up to 16 separate contacts, for example, 12 make and 4 break contacts. Many of these relays come in 12V, 24V and 50V versions.

The BR Q-type relay are available in a number of different configurations:

- QN1 Neutral

- QL1 Latched - see above

- QNA1 AC-immune

- QBA1 Biased AC-immune - see above

- QNN1 Twin Neutral 2x4-4 or 2x6-2

- QBCA1 Contactor for high current applications such as point motors. Also DC biased and AC immune.[24]

- QTD4 - Slow to release timer [25]

- QTD5 - Slow to pick up timer [26]

Since rail signal circuits must be highly reliable, special techniques are used to detect and prevent failures in the relay system. To protect against false feeds, double switching relay contacts are often used on both the positive and negative side of a circuit, so that two false feeds are needed to cause a false signal. Not all relay circuits can be proved so there is reliance on construction features such as carbon to silver contacts to resist lightning induced contact welding and to provide AC immunity.

Opto-isolators are also used in some instances with railway signalling, especially where only a single contact is to be switched.

Signalling relays, typical circuits, drawing symbols, abbreviations & nomenclature, etc. come in a number of schools, including the United States, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

See also

- Contactor

- Digital protective relay

- Dry contact

- Race condition

- Stepping switch - a kind of multi-position relay

- Wire spring relay

- Analogue switch

- Nanoelectromechanical relay

References

- ↑ Icons of Invention: The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates. ABC-CLIO. p. 153.

- ↑ "The electromechanical relay of Joseph Henry". Georgi Dalakov.

- ↑ Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries: All the Milestones in Ingenuity--From the Discovery of Fire to the Invention of the Microwave Oven. John Wiley & Sons. p. 311.

- ↑ Thomas Coulson (1950). Joseph Henry: His Life and Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?ei=xPkZVZ3BFNbWavGogpAO&id=xjUhAQAAIAAJ&dq=Early+Electrical+Communication&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Henry+Relay

- ↑ Gibberd, William (1966). "Edward Davy". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ US Patent 1,647, Improvement in the mode of communicating information by signals by the application of electro-magnetism, June 20, 1840

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?allowed_in_frame=0&search=relay&searchmode=none

- ↑ Mason, C. R. "Art & Science of Protective Relaying, Chapter 2, GE Consumer & Electrical". Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- 1 2 Sinclair, Ian R. (2001), Sensors and Transducers (3rd ed.), Elsevier, p. 262, ISBN 978-0-7506-4932-2

- 1 2 A. C. Keller. "Recent Developments in Bell System Relays -- Particularly Sealed Contact and Miniature Relays". The Bell System Technical Journal. 1964.

- ↑ Ian Sinclair, Passive Components for Circuit Design, Newnes, 2000 ISBN 008051359X, page 170

- ↑ Kenneth B. Rexford and Peter R. Giuliani (2002). Electrical control for machines (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7668-6198-5.

- ↑ Terrell Croft and Wilford Summers (ed), American Electricians' Handbook, Eleventh Edition, McGraw Hill, New York (1987) ISBN 0-07-013932-6 page 7-124

- ↑ Zocholl, Stan (2003). AC Motor Protection. Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc. ISBN 978-0972502610.

- ↑ Safety Compendium, Chapter 4 Safe control technology, p. 115

- ↑ EN 50005:1976 "Specification for low voltage switchgear and controlgear for industrial use. Terminal marking and distinctive number. General rules." (1976). In the UK published by BSI as BS 5472:1977.

- ↑ "Relay Automatic Telephone Company". Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "British Telecom History 1912-1968". Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- 1 2 "Arc Suppression to Protect Relays From Destructive Arc Energy". Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ↑ Al L Varney. "Questions About The No. 1 ESS Switch". 1991.

- ↑ "Lab Note #105 Contact Life - Unsuppressed vs. Suppressed Arcing". Arc Suppression Technologies. April 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.morssmitt.com/railway/qstylests.htm

- ↑ http://www.morssmitt.com/railway/signalling-infrastructure/signalling-relays/q-style-br930-signalling-relays/qbca1-ac-immune-dc-biased-contactor-relay/

- ↑ http://www.morssmitt.com/railway/signalling-infrastructure/signalling-relays/q-style-br930-signalling-relays/qtd4-slow-to-release-delay-units/

- ↑ http://www.morssmitt.com/railway/signalling-infrastructure/signalling-relays/q-style-br930-signalling-relays/qtd5-slow-to-operate-relays/

- Gurevich, Vladimir (2005). Electrical Relays: Principles and Applications. London - New York: CRC Press.

- Westinghouse Corporation (1976). Applied Protective Relaying. Westinghouse Corporation. Library of Congress card no. 76-8060.

- Terrell Croft and Wilford Summers (ed) (1987). American Electricians' Handbook, Eleventh Edition. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-013932-9.

- Walter A. Elmore. Protective Relaying Theory and Applications. Marcel Dekker kana, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8247-9152-0.

- Vladimir Gurevich (2008). Electronic Devices on Discrete Components for Industrial and Power Engineering. London - New York: CRC Press. p. 418.

- Vladimir Gurevich (2003). Protection Devices and Systems for High-Voltage Applications. London - New York: CRC Press. p. 292.

- Vladimir Gurevich (2010). Digital Protective Relays: Problems and Solutions. London - New York: CRC Press. p. 422.

- Colin Simpson, Principles of Electronics, Prentice-Hall, 2002, ISBN 978-0-9686860-0-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relay. |

- Abdelmoumene, Abdelkader, and Hamid Bentarzi. "A review on protective relays' developments and trends." Journal of Energy in Southern Africa 25.2 (2014): 91-95. http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/jesa/v25n2/10.pdf http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?pid=S1021-447X2014000200010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt

- Electromagnetic relays and Solid-State Relays (SSR), general technical descriptions, functions, shutdown behaviour and design features

- The Electromechanical Relay

- Information about relays and the Latching Relay circuit

- "Harry Porter's Relay Computer", a computer made out of relays.

- "Relay Computer Two", by Jon Stanley.

- Interfacing Relay To Microcontroller.

- Relays Technical Write, by O/E/N India Limited

|