Ovambo people

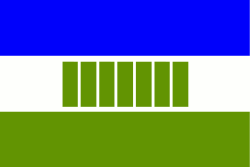

Flag of Ovamboland | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (~ 1,079,000 [1]) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 654,000[1] | |

| 425,000[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Oshiwambo | |

| Religion | |

| Lutheran | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Bantu peoples | |

The Aawambo or Ambo people (endonyms Aawambo [Ndonga], Ovawambo [Kwanyama]) consist of a number of kindred Bantu ethnic groups which inhabit Owamboland in northern Namibia as well as the southernmost Angolan province Cunene. In Namibia, these are the AaNdonga, Ovakwanyama, Aakwambi, Aangandjera, Aambalantu, Ovaunda, Aakolonkadhi and Aakwaluudhi. In Angola, they are the Ovakwanyama, Aakafima, Evale and Aandonga. They are the largest ethnic group in Namibia.

The Ambo people migrated south from the upper regions of Zambezi and currently make up the greatest population in Namibia. The reason that they settled in the area where they now live was for the rich soil that is scattered around the Owamboland. The Ambo population is overall roughly 1,500,000.

The Ambo are part of the greater Bantu family. They speak Oshiwambo, which includes the Oshikwanyama, Oshingandjera, Oshindonga and other dialects.

Geography

Flat sandy plains of Northern Namibia and Southern Angola make up Ovamboland, with water courses that bisect the area. These are known as oshanas. In the northern regions of the Owamboland there are thick belts of tropical vegetation. The average rainfall in this area is around 17 inches during the rainy season. The oshanas can become flooded and sometimes submerge three-fifths of the region. This poses a unique problem for the Ambo people as they have to adapt to the changing weather patterns. In the dry season they are able to use the grassy plains for stock to graze upon.

The Aawambo have been able to adapt to their land and their environment. They raise cattle, fish in the oshanas, and farm. They are skilled craftsmen. They make and sell basketry, pottery, jewelry, wooden combs, wood iron spears, arrows, richly decorated daggers, musical instruments, and also ivory buttons

Culture and beliefs

In recent times, most Aawambo consider themselves Lutheran. Finnish missionaries arrived in Owamboland in the 1870s and converted the Aawambo, in the process causing most of the traditional beliefs to die out. As a result of the missionaries, almost all Aawambo people wear Western-style clothes and listen to Western-style music. They still have traditional dancing that involves drumming (Oshiwambo folk music). Most weddings are a combination of Christian beliefs and Aawambo traditions.

The traditional home is built as a group of huts surrounded by a fence of large vertical poles. Some families also build a Western-style cement block building within the home. Each hut generally has a different purpose, such as a Ondjugo, storeroom, or Elugo, kitchen. Most families collect water from a nearby public water well or tap.

Most families have a large plot of land, and their primary crop is millet, which is made into a thick Oshimbombo. They also grow beans, watermelons, squash, and sorghum. Most households own a few goats and cattle, and occasionally a few pigs. It is the job of the young men to attend to the goats and cattle, taking them to find grazing areas during the day, and bringing them back to the home in the evening. Most houses have chickens, which roam freely. Like most farms, dogs and cats are common pets. When the rains come, the rivers to the north in Angola overflow and flood the area, bringing fish, birds, and frogs.

Traditionally, the Owambo people lived a life that was highly influenced by a combination of magic and religion. They not only believed in good and evil spirits but also they are influenced by missionaries and the majority are Lutheran or Catholic.

Beliefs among the Owambo people centre around their belief in Kalunga. For example, when a tribe member wants to enter the chief's kraal, they must first remove their sandals. It is said that if this person does not remove their sandals it will bring death to one of the royal inmates and throw the kraal into mourning. Another belief deals with burning fire in the chief's kraal. If the fire burns out, the chief and the tribe will disappear. An important ceremony takes place at the end of the harvest, where the entire community has a feast and celebrates.

Each tribe has a chief that is responsible for the tribe, although many have converted to running tribal affairs with a council of headmen. Members of the royal family of the Owamboland are known as aakwanekamba and only those who belong to this family by birth have a claim to chieftainship. Because descent is matrilineal, these relations must fall on the mother's side. The chief's own sons have no claim in the royal family. They grow up as regular members of the tribe.

Ovambo brew a traditional liquor called Ombike. It is distilled from fermented fruit mash and particularly popular in rural areas. The fruit to produce Ombike are collected from Makalani Palms, Jackal Berries, Buffalo Thorns, Bird Plumes and Cluster Figs. Ombike with additives like sugar is brewed and consumed in urban areas. This liquor is then called omangelengele, it is more potent and sometimes poisonous. New Era, one of the English daily newspapers, reported that even clothes, shoes, and tyres can be ingredients of omangelengele.[2]

Ovambo tribes

The following table contains the names, areas, dialect names and the locations of the Ovambo tribes according to T. E. Tirronen's Ndonga-English Dictionary. The table also contains information concerning which noun class of the Proto-Bantu language the words belong to.[3]

| Area | Tribe | Dialect | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classes 9 (*ny > on-), 11 (uu-/ou-) | Class 2 (*wa-, a-) | Class 7 (*ki > oshi-) | |

| O-ndonga | Aa-ndonga | Oshi-ndonga | Southern Ovamboland |

| Uu-kwambi | Aa-kwambi | Oshi-kwambi | Central Ovamboland |

| O-ngadjera | Aa-ngandjera | Oshi-ngandjera | Central Ovamboland |

| Uu-kwaluudhi | Aa-kwaluudhi | Oshi-kwaluudhi | Western Ovamboland |

| O-mbalanhu | Aa-mbalanhu | Oshi-mbalanhu | Western Ovamboland |

| Uu-kolonkadhi | Aa-kolonkadhi | Oshi-kolonkadhi | Western Ovamboland |

| Ou-kwanyama | Ova-kwanyama | Oshi-kwanyama | Northern and Eastern Ovamboland, Angola |

| E-unda | Ova-unda | Oshi-unda | Western Ovamboland, Epalela vicinity |

| O-mbadja | Ova-mbadja | Oshi-mbadja | Southern Angola, Shangalala region |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "The Ambo, Ndonga people group are reported in 2 countries". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ Shaanika, Helvy (26 October 2012). "Ombike – a potent traditional brew". New Era.

- ↑ Toivo Emil Tirronen: Ndonga-English Dictionary. Oshinyanyangidho shongeleki ELCIN. Oniipa, 1986.

Bibliography

- (German) Karl Angebauer, Ovambo : Fünfzehn Jahre unter Kaffern, Buschleuten und Bezirksamtmännern, A. Scherl, Berlin, 1927, 257 p.

- (German) P. H. Brincker, Unsere Ovambo-Mission sowie Land, Leute, Religion, Sitten, Gebräuche, Sprache usw. der Ovakuánjama-Ovámbo, nach Mitteilungen unserer Ovambo-Missionare zusammengestellt, Barmen, 1900, 76 p.

- (German) Wolfgang Liedtke & Heinz Schippling, Bibliographie deutschsprachiger Literatur zur Ethnographie und Geschichte der Ovambo, Nordnamibia, 1840–1915, annotiert, Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden, Dresde, 1986, 261 p.

- Teddy Aarni, The Kalunga concept in Ovambo religion from 1870 onwards, University of Stockholm, Almquist & Wiksell, 1982, 166 p. ISBN 91-7146-301-1.

- Leonard N. Auala, The Ovambo : our problems and hopes, Munger Africana Library, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena (Cal.), 1973, 32 p.

- Allan D. Cooper, Ovambo politics in the twentieth century, University Press of America, Lanham, Md., 2001, 350 p. ISBN 0-7618-2110-4.

- Gwyneth Davies, The medical culture of the Ovambo of Southern Angola and Northern Namibia, University of Kent at Canterbury, 1993 (thesis)

- Patricia Hayes, A history of the Ovambo of Namibia, c 1880-1935, University of Cambridge, 1992 (thesis)

- Maija Hiltunen, Witchcraft and sorcery in Ovambo, Finnish Anthropological Society, Helsinki, 1986, 178 p. ISBN 951-95434-9-X

- Maija Hiltunen, Good magic in Ovambo, Finnish Anthropological Society, Helsinki, 1993, 234 p. ISBN 952-9573-02-2

- Matti Kuusi, Ovambo proverbs with African parallels, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki, 1970, 356 p.

- Carl Hugo Linsingen Hahn, The native tribes of South-West Africa : The Ovambo - The Berg Damara - The bushmen of South West Africa - The Nama - The Herero, Cape Times Ltd., Le Cap, 1928, 211 p.

- Seppo Löytty, The Ovambo sermon : a study of the preaching of the Evangelical Lutheran Ovambo-Kavango Church in South West Africa, Luther-Agricola Society, Tampere (Finland), 1971, 173 p.

- Giorgio Miescher, The Ovambo Reserve Otjeru (1911–1938) : the story of an African community in Central Namibia, Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Bâle, 2006, 22 p.

- Ramiro Ladeiro Monteiro, Os ambós de Angola antes da independência, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Lisbon, 1994, 311 p. (thesis, in (Portuguese))

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||