Outside the Law (2010 film)

| Outside the Law | |

|---|---|

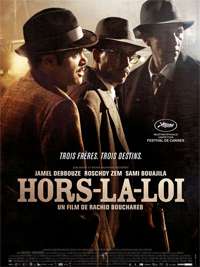

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Rachid Bouchareb |

| Produced by | Jean Bréhat |

| Written by |

Rachid Bouchareb Olivier Lorelle |

| Starring |

Jamel Debbouze Roschdy Zem Sami Bouajila |

| Music by | Armand Amar |

| Cinematography | Christophe Beaucarne |

| Edited by | Yannick Kergoat |

Production company |

Tessalit Productions |

| Distributed by | StudioCanal (France) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 137 minutes |

| Country |

France Algeria Tunisia Belgium |

| Language |

French Arabic |

| Budget | € 19.5 million |

Outside the Law (French: Hors-la-loi, Arabic: خارجون عن القانون) is a 2010 drama film directed by Rachid Bouchareb, starring Jamel Debbouze, Roschdy Zem and Sami Bouajila. The story takes place between 1945 and 1962, and focuses on the lives of three Algerian brothers in France, set against the backdrop of the Algerian independence movement and the Algerian War.[1] It is a stand-alone follow-up to Bouchareb's 2006 film Days of Glory, which was set during World War II. Outside the Law was a French majority production with co-producers in Algeria, Tunisia and Belgium.

An historically unorthodox portrayal of the 1945 Sétif massacre sparked a political controversy in France. Reviews of the film compared it to Westerns and gangster films, and critics observed how the independence activists were likened to the French Resistance during World War II. Outside the Law represented Algeria at the 83rd Academy Awards, where it was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film.

Cast

- Jamel Debbouze as Saïd

- Roschdy Zem as Messaoud

- Sami Bouajila as Abdelkader

- Bernard Blancan as Colonel Faivre

- Chafia Boudraa as the mother

- Sabrina Seyvecou as Hélène

- Assaad Bouab as Ali

- Thibault De Montalembert as Morvan

- Samir Guesmi as Otmani

- Jean-Pierre Lorit as Picot

- Ahmed Benaissa as the father

- Larbi Zekkal as Le caïd

- Louiza Nehar as Zohra

- Mourad Khen as Sanjak

- Mohamed Djouhri as the trainer

- Mustapha Bendou as Brahim

- Abdelkader Secteur as Hamid

Production

Outside the Law was not written as a direct sequel to Rachid Bouchareb's 2006 film Days of Glory, about Africans who fought for France in World War II, but shares many of the main actors, and starts at the place in history where the previous film ended. Bouchareb said, "You can't help but associate them, because it's the same soldiers who fought for France against Germany, a lot of them were the same soldiers that later went on to fight France. So, historically speaking, the same group of people had a lot going on early in their lives. When I was interviewing people for Days of Glory, a lot of the people I was talking to were also telling me what happened after, which is how I came to write the other movie."[2] Bouchareb researched the subject for nine months, primarily by interviewing people. Finishing the screenplay took two years.[2]

The film was written with actors Jamel Debbouze, Roschdy Zem and Sami Bouajila in mind from the beginning. Debbouze described his role's place as the youngest brother, and stronger ties to the family, as a key for approaching the character.[3] Zem's character was inspired by the character played by Sterling Hayden in The Asphalt Jungle. Zem said, "When I saw the movie, it was obvious what Rachid was looking for: a combination of brute force and restraint."[3] Bouajila said about developing his character, "I tried to work out how, through his convictions or pride, a man can fall into the trap of his own charisma and drag other people with him. When everything spirals out of his control, he has to face himself and realizes that he is only a man."[3]

The 19.5 million euro production was led by France's Tessalit Productions in co-production with France 2, France 3 and companies in Algeria, Tunisia and Belgium. Funding was granted by the National Center of Cinematography and via pre-sales to Canal+.[1] Out of the total investment, 59% came from France, 21% Algeria, 10% Tunisia and 10% Belgium.[4]

Filming began at the end of July 2009 and lasted five months.[1] Approximately 90% of the film was shot in the studio.[2] The team moved between facilities and locations in Paris, Algeria, Tunisia, the Belgian cities Charleroi and Brussels, Germany and the United States, with scenes set at the United Nations Headquarters.[1]

Reception

The film premiered on 21 May 2010, in competition at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.[5] French distribution was handled by StudioCanal and the premiere took place on 22 September 2010.[6] It was released in Algeria on 6 October of the same year.[7] In the United States, the film was distributed through Cohen Media Group, which released it in New York on 3 November, Los Angeles on 10 November and in a limited run throughout the country on 26 November.[8]

Critical response

François-Guillaume Lorrain of Le Point compared the film's narrative to film noir and Western films such as The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Lorrain argued that the form resulted in exaggeration and clumsiness, which burdened the film, and evoked questions about the balance between cinema as a conveyor of truth and cinema as light entertainment. Lorrain noted that, with a couple of exceptions, "the French have the villainous role ... with a comparison that risks to make teeth grind: the French are likened to the Germans when the Algerians endorse the costumes of resistance members. Difficult to leave Outside the Law without a feeling of guilt, already caused with Days of Glory by Bouchareb, who, by filming the opposite Maghrebin side, presses where it hurts in the official history of France. At the same time, he doesn't provide a rosy picture of the FLN, far from that."[9] Le Monde's Thomas Sotinel criticised the film for using stereotypes, and how too much artifice in the narrative "stifles the efforts of the actors," concluding that "Outside the Law collapses under the weight of the spectacle."[10]

Regarding the controversies, Fayçal Métaoui, who reviewed the film for the Algerian newspaper El Watan, wrote, "Some French critics believed they saw 'an unacceptable parallel' between the struggle against the hideous Nazi regime and the French colonial presence in Algeria. This does not seem to be the intention of Outside the Law, as the aim was to show that France hadn't held a certain promise to the Algerians ... The film, which is perfect on the aesthetical level and far from a turkey, may be entered in the anti-colonial register but not anti-French."[11] Métaoui also complimented that Bouchareb had chosen to portray the violent clashes between the Algerian National Movement and the National Liberation Front, an episode "the official Algerian history has completely ignored".[12]

The Philadelphia Inquirer published a review by Carrie Rickey, who wrote, "Under the obvious influence of Francis Ford Coppola, Bouchareb frames his shadow-ridden guerrilla heroes as the Algerian counterparts of the Corleones", referring to the American film The Godfather, and further that Outside the Law owes "an enormous debt to Jean-Pierre Melville's Army of Shadows (1969), about French resistance fighters one-minded in their goal to subvert Nazis". Rickey wrote, "Bouchareb is sometimes a little too one-minded: His movie might have been richer emotionally had he written scenes showing the characters' domestic lives and not strictly their professional spheres."[13]

Stephen Holden of The New York Times called Outside the Law a "didactic, unashamedly manipulative film", and also saw parallels to The Godfather and Army of Shadows: "Those are mighty shoes to fill, and as powerful and well-made as it is, Outside the Law is too schematic and single-minded to lodge itself in your mind as a fully realized cinematic epic. Its few female characters are sketchy at best."[14]

Historical criticism

Historians were critical of the film's ahistorical nature. Guy Pervillé deplored the inevitable acceptance by moviegoers of the film's myth as representing historical truth.[15]

Political reactions

Before the film premiered, already it was met by political controversy in France. Lionnel Luca, a member of the National Assembly for the UMP, appealed for a review by the Defence Historical Service as soon as he heard about the project. After having studied the script, the Defence Historical Service concluded that "the errors and anachronisms are so many and so gross that they can be identified by any historian ... The numerous improbabilities present in the scenario show that the writing of the latter was not preceded by a serious historical study."[16] The center of the controversy was the depiction of the 1945 Sétif massacre early in the film. The report elaborated, "The director wants to suggest that on May 8, 1945, Muslims in Sétif were blindly massacred by Europeans, whereas it's the contrary that transpired[.] ... [A]ll historians agree that ... Europeans lashed out against Muslims in response to Muslims massacring Europeans."[17] This reaction is at odds with mainstream history, which concluded that, after restoring order in the town, French military and police then carried out a series of reprisals and summary executions of native civilians. Luca also criticized the decision to give public funding to a film which he considered "anti-French".[18] Mustapha Orif, one of the film's co-producers, responded to the accusations and defended the film's portrayal of the massacre. "Rachid Bouchareb interviewed many people, witnesses and historians. From this point of view, I do not think at all that he has deviated from historical reality," he said.[19]

Box office

The film opened on 400 screens in France, with 195,242 admissions after one week, which equaled a fifth place on the domestic box-office chart. The number of screens was increased to 437 for the second week, but the film dropped to eighth place on the chart. When the theatrical run ended, a total of 393,335 tickets had been sold.[20] This was considerably less than the 3,227,502 that Days of Glory attained four years earlier.[21] As of 10 April 2011, Box Office Mojo reported that the worldwide revenues of Outside the Law corresponded to 3,298,780 US dollars.[22]

Accolades

The film was nominated for Best Screenplay at the 16th Lumière Awards, voted by foreign journalists who work in Paris.[23] It was selected as one of the five nominees for Best Foreign Language Film at the 83rd Academy Awards, having been submitted by Algeria.[24] It was the third time a film directed by Bouchared was nominated in the category, after Dust of Life in 1996 and Days of Glory in 2007.[4]

Sequel

Bouchareb has stated his desire to make a third installment that would end a trilogy that started with Days of Glory and continued with Outside the Law. He hopes to be able to produce it four or five years after Outside the Law. It will be a thematical continuation of the two previous films and focus on "50 years of immigration".[25]

See also

- Algeria–France relations

- Beur

- List of Algerian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of submissions to the 83rd Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Lemercier, Fabien (2009-07-23). "Bouchareb launches into Outside the Law". Cineuropa. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- 1 2 3 Truax, Jackson (2010-12-03). "Interview: Rachid Bouchareb". awardscircuit.com. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- 1 2 3 "Outside the Law Press Kit". StudioCanal. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- 1 2 Lemercier, Fabien (2011-01-25). "Outside the Law, The Illusionist stay in race". Cineuropa. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ↑ "The screenings guide" (PDF). festival-cannes.com. Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Film profile: Outside the Law". Cineuropa. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ Kaddour, Tegguer (2010-09-30). "Hors la loi pour le 6 octobre prochain". El Watan (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ↑ Mowe, Richard (2010-12-04). "Outside the Law (Hors la loi)". Box Office Magazine. Box Office Media. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ Lorrain (2010) "les Français ont le mauvais rôle ... avec une comparaison qui risque de faire grincer des dents : les Français sont assimilés aux Allemands quand les Algériens endossent les habits des résistants. Difficile de ne pas sortir de Hors-la-loi avec un sentiment de culpabilité, provoqué déjà par Indigènes de Bouchareb, qui, en filmant le contrechamp maghrébin, appuyait là où cela fait mal dans l'histoire officielle de la France. Dans le même temps, il n'offre pas un tableau idyllique du FLN, loin de là."

- ↑ Sotinel (2010) "étouffent les efforts des acteurs", "Hors-la-loi s'effondre sous le poids du spectacle."

- ↑ Métaoui (2010) "Certains critiques français ont cru déceler « un parallèle inacceptable » entre la lutte contre le régime hideux du nazisme et la présence coloniale française en Algérie. Cela ne semble pas être le cas de l'intention de « Hors la loi » puisque le but était de montrer que la France n'avait pas tenu une certaine promesse faite aux algériens. ... Le film, parfait sur le plan esthétique et qui est loin d'être un navet, peut être inscrit dans le registre anti-colonialiste mais pas anti français."

- ↑ Métaoui (2010) "L'histoire officielle algérienne a complètement ignoré l'épisode"

- ↑ Rickey, Carrie (2011-02-18). "Algerian resistance with gangster feel". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ↑ Holden, Stephen (2010-11-02). "Algerian Brothers Reunite in Paris, Outrage Still Burning". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ↑ Guy Pervillé (3 October 2010), Réponse à Thierry Leclère (2010) (in French)

- ↑ Hugues (2010) "les erreurs et les anachronismes sont si nombreux et si grossiers qu'ils peuvent être relevés par tout historien. ... Les nombreuses invraisemblances présentes dans le scénario montrent que la rédaction de ce dernier n'a pas été précédée par une étude historique sérieuse."

- ↑ Staff writer (2010-05-01). "Bouchareb film slammed for 'falsifying' history of French-Algerian massacre". france24.com. France 24. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ Hugues (2010) "ce film anti-français"

- ↑ Hugues (2010) "Rachid Bouchareb a interrogé beaucoup de gens, de témoins et d'historiens. De ce point de vue, je ne pense pas du tout qu'il se soit écarté de la réalité historique."

- ↑ "Hors-la-loi (2010)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Indigènes (Days of Glory) (2006)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Outside the Law (Hors-la-loi)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ↑ Lemercier, Fabien (2010-12-21). "Of Gods and Men leads Lumière nominations". Cineuropa. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ↑ "Nominees for the 83rd Academy Awards". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ Staff writer (2010-10-18). "Interview with Rachid Bouchareb". dohafilminstitute.com. Doha Film Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- Articles

- Hugues, Bastien (2010-04-29). "Polémique autour du prochain film de Rachid Bouchareb". Le Figaro (in French). Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- Lorrain, François-Guillaume (2010-09-21). "Hors-la-loi, le film qui fait débat". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Sotinel, Thomas (2010-09-21). "'Hors-la-loi' : rebelles académiques". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Métaoui, Fayçal (2010-10-07). "Boue d’hier, mensonge d’aujourd’hui". El Watan (in French). Retrieved 2011-01-27.

External links

- Official website

- Official website (USA)

- Outside the Law at the Internet Movie Database

- Outside the Law at Rotten Tomatoes