Ouranosaurus

| Ouranosaurus Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, 125–112 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton cast, ROM | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Styracosterna |

| Clade: | †Hadrosauriformes |

| Genus: | †Ouranosaurus Taquet, 1976 |

| Species: | † O. nigeriensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ouranosaurus nigeriensis Taquet, 1976 | |

Ouranosaurus (meaning "brave (monitor) lizard") is a genus of herbivorous iguanodont dinosaur that lived during the early Cretaceous (late Aptian age) at some point between 125 and 112 million years ago, in what is now Africa. Ouranosaurus measured about 7 to 8.3 metres long (23 to 27 ft). Two rather complete fossils were found in the Echkar (or El Rhaz) Formation, Gadoufaoua deposits, Agadez, Niger, in 1965 and 1972.[1] The animal was named in 1976 by French paleontologist Philippe Taquet; the type species being Ouranosaurus nigeriensis.

Description

Ouranosaurus was a relatively large euornithopod. Taquet in 1976 estimated the body length at 7 metres (23 feet), the weight at four tonnes. Gregory S. Paul in 2010 gave a higher length estimate of 8.3 metres (27 feet) but a lower weight of 2.2 tonnes, emphasizing that the animal was relatively lightly built.[2] The femur is 811 millimetres long.

Postcranial skeleton

The most conspicuous feature of Ouranosaurus is a large "sail" on its back, supported by long, wide, neural spines, that spanned its entire rump and tail, resembling that of Spinosaurus, a well-known meat-eating dinosaur that lived around the same time.[1][3] These tall neural spines did not closely resemble those of sail-backs such as Dimetrodon of the Permian Period. The supporting spines in a sailback become thinner distally, whereas in Ouranosaurus the spines actually become thicker distally and flatten. The posterior spines were also bound together by ossified tendons, which stiffened the back. Finally, the spine length peaks over the forelimbs.

The first four dorsal vertebrae are unknown; the fifth already bears a 32 centimetres long spine that is pointed and slightly hooked; Taquet presumed it might have anchored a tendon to support the neck or skull. The tenth, eleventh and twelfth spines are the longest at about 63 centimetres. The last dorsal spine, the seventeenth, has a grooved posterior edge, in which the anterior corner of the lower spine of the first sacral vertebra is locked. The spines over the six sacral vertebrae are markedly lower, but those of the tail base again longer; towards the end of the tail the spines gradually shorten.

The dorsal "sail" is usually explained as either functioning as a system for thermoregulation or a display structure. An alternative hypothesis is that the back might have carried a hump consisting of muscle tissue or fat, resembling that of a bison or camel, rather than a sail. It could have been used for energy storage to survive a lean season.[4]

The axial column consisted of eleven neck vertebrae, seventeen dorsal vertebrae, six sacral vertebrae and forty tail vertebrae. The tail was relatively short.

The front limbs were rather long with 55% of the length of the hind limbs. A quadrupedal stance would have been possible. The humerus was very straight. The hand was lightly built, short and broad. On each hand Ouranosaurus bore a thumb claw or spike that was much smaller than that of the earlier Iguanodon. The second and third digits were broad and hoof-like, and anatomically were good for walking. To support the walking hypothesis, the wrist was large and its component bones fused together to prevent its dislocation. The last digit (number 5) was long. In related species the fifth finger is presumed to have been prehensile: used for picking food like leaves and twigs or to help lower the food by lowering branch to a manageable height. Taquet assumed that with Ouranosaurus this function had been lost because the fifth metacarpal, reduced to a spur, could no longer be directed sideways.

The hindlimbs were large and robust to accommodate the weight of the body and strong enough to allow a bipedal walk. The femur was slightly longer than the tibia. This may indicate that the legs were used as pillars, and not for sprinting. Taquet concluded that Ouranosaurus was not a good runner because the fourth trochanter, the attachment point for the large retractor muscles connected to the tail base, was weakly developed. The foot was narrow with only three toes and relatively long.

In the pelvis, the prepubis was very large, rounded and directed obliquely upwards.

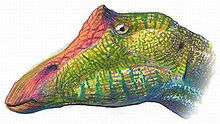

Skull

Ouranosaurus had a skull 67 centimetres long. The head was very elongated and flat, and carried a much longer snout than its relative Iguanodon: this rostrum was not curved but straight, off-set from the back of the skull in an oblique line. The snout was toothless and covered in a horny sheath during life, forming a very wide beak together with a comparable sheath on the short predentary bone at the extreme front of the lower jaws. However, after a rather large diastema with the beak, there were large batteries of cheek teeth on the sides of the jaws: the gaps between the teeth crowns were filled by the points of a second generation of replacement teeth, the whole forming a continuous surface. Contrary to the situation with some related species, a third generation of erupted teeth was lacking. There were twenty-two tooth positions in both lower and upper jaw for a total of eighty-eight.

The jaws were apparently operated by relatively weak muscles. Ouranosaurus had only small temporal openings behind the eyes, from which the larger capiti-mandibularis muscle was attached to the coronoid process on the lower jaw bone. Small rounded horns in front of its eyes made Ouranosaurus the only known horned Ornithopod.[1] The back of the skull was rather narrow and could not compensate for the lack of a greater area of attachment for the jaw muscle, that the openings normally would provide, allowing for more power and a stronger bite. A lesser muscle, the musculus depressor mandibulae, used to open the lower jaws, was located at the back of the skull and was connected to a strongly projecting, broad and anteriorly oblique processus paroccipitalis. Ouranosaurus probably used its teeth to chew up tough plant food. A diet has been suggested of leaves, fruit, and seeds as the chewing would allow to free more energy from high quality food;[3] the wide beak on the other hand indicates a specialisation in eating large amounts of low quality fodder. Ouranosaurus lived in a river delta.

The nasal passage was large and placed close to the beak. The nostrils were in a high position. On each side of the top of the skull there was a low bump between the nasal opening and the eye socket; the significance of both protuberances is unknown, but they may have been used for socialisation or mating displays. A secondary palpebral bone was lacking.

Discovery and naming

In January 1965 Philippe Taquet discovered dinosaurian fossils at the Camp des deux Arbres site near Gadoufaoua. The material was recovered in 1966. Taquet described the type species Ouranosaurus nigeriensis from the fossils in 1976. The generic name is derived from Tuareg ourane meaning "monitor lizard" — a totem animal to the Tuareg who consider it their ancestral maternal uncle — but itself related to Arab waran, "brave". The specific name refers to Niger.[5]

The holotype specimen MNHN GDF 300, was found in the Upper Elrhaz Formation dating to the Aptian, between 125 and 112 million years old.[6][7] It consists of an almost complete skeleton with skull, that is today mounted in the Nigerien capital Niamey; the Museum national d'histoire naturelle displays a cast. Other finds include the paratype specimen GDF 381, a second skeleton found in 1972, and the referred specimens GDF 301, a large coracoid, and GDF 302, a femur.

Classification

Taquet originally assigned Ouranosaurus to the Iguanodontidae, within the larger Iguanodontia. However, although it shares some similarities with Iguanodon (such as a thumb spike), Ouranosaurus is no longer placed in the iguanodontid family, a grouping that is now considered paraphyletic, a series of subsequent offshoots from the main stem-line of iguandontian evolution. It is instead placed in the clade Hadrosauroidea, which contains the Hadrosauridae (also known as "duck-billed dinosaurs") and their closest relatives. Ouranosaurus appears to represent an early specialised branch in this group, showing in some traits independent convergence with the hadrosaurids. It is thus a basal hadrosauroid.

The simplified cladogram below follows an analysis by Andrew McDonald and colleagues, published in November 2010 with information from McDonald, 2011.[8][9]

| Iguanodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleoecology

The Elrhaz Formation consists mainly of fluvial sandstones with low relief, much of which is obscured by sand dunes.[10] The sediments are coarse- to medium-grained, with almost no fine-grained horizons.[11] Nigersaurus lived in what is now Niger about 115 to 105 million years ago, during the Aptian and Albian ages of the mid-Cretaceous.[12] It likely lived in habitats dominated by inland floodplains (a riparian zone).[11]

After the iguanodontian Lurdusaurus, Nigersaurus was the most numerous megaherbivore.[11] Other herbivores from the same formation include Ouranosaurus, Elrhazosaurus, and an unnamed titanosaur. It also lived alongside the theropods Kryptops, Suchomimus, and Eocarcharia, and a yet-unnamed noasaurid. Crocodylomorphs like Sarcosuchus, Anatosuchus, Araripesuchus, and Stolokrosuchus also lived there. In addition, remains of a pterosaur, chelonians, fish, a hybodont shark, and freshwater bivalves have been found.[10] Grass did not evolve until the late Cretaceous, making ferns, horsetails, and angiosperms (which had evolved by the middle Cretaceous) potential food for Nigersaurus. It is unlikely the dinosaur fed on conifers, cycads, or aquatic vegetation, due respectively to their height, hard and stiff structure, and lack of appropriate habitat.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Edinburgh, Scotland: Dorling Kindersley. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- ↑ Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 292

- 1 2 Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 144. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Bailey, J.B. (1997). "Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs?". Journal of Paleontology (71): 1124–1146.

- ↑ Taquet, P. 1976. Geologie et paleontologie du gisement de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger), Cahier Paleont., C.N.R.S. Paris, 1-191

- ↑ P. Taquet, 1970, "Sur le gisement de Dinosauriens et de Crocodiliens de Gadoufaoua (République du Niger)", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences à Paris, Série D 271: 38-40

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ↑ McDonald, A.T.; Kirkland, J.I.; DeBlieux, D.D.; Madsen, S.K.; Cavin, J.; Milner, A.R.C.; Panzarin, L. (2010). Farke, Andrew Allen, ed. "New Basal Iguanodontians from the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah and the Evolution of Thumb-Spiked Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE 5 (11): e14075. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014075. PMC 2989904. PMID 21124919.

- ↑ Andrew T. McDonald (2011). "The taxonomy of species assigned to Camptosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Zootaxa 2783: 52–68.

- 1 2 Sereno, P. C.; Brusatte, S. L. (2008). "Basal abelisaurid and carcharodontosaurid theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53 (1): 15–46. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0102.

- 1 2 3 4 Sereno, P. C.; Wilson, J. A.; Witmer, L. M.; Whitlock, J. A.; Maga, A.; Ide, O.; Rowe, T. A. (2007). "Structural extremes in a Cretaceous dinosaur". PLoS ONE 2 (11): e1230. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001230. PMC 2077925. PMID 18030355..

- ↑ Sereno, P. C.; Beck, A. L.; Dutheil, D. B.; Larsson, H. C.; Lyon, G. H.; Moussa, B.; Sadleir, R. W.; Sidor, C. A.; Varricchio, D. J.; Wilson, G. P.; Wilson, J. A. (1999). "Cretaceous sauropods from the Sahara and the uneven rate of skeletal evolution among dinosaurs". Science 286 (5443): 1342–1347. doi:10.1126/science.286.5443.1342. PMID 10558986.

Sources

- Ingrid Cranfield, ed. (2000). Dinosaurs and other Prehistoric Creatures. Salamander Books. pp. 152–154.

- Richardson, Hazel. Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals. Smithsonian Handbooks. p. 108.

- Dixon, Dougal (2006). The Complete Book of Dinosaurs. Hermes House.

- Cox, Barry; Colin Harrison, R.J.G. Savage, and Brian Gardiner (1999). The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Ouranosaurus on Nature

- Ouranosaurus (with picture)

- Iguanodontia at Thescelosaurus