Ottoman miniature

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

|

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

Ottoman miniature or Turkish miniature was an art form in the Ottoman Empire, which can be linked to the Persian miniature tradition,[1] as well as strong Chinese artistic influences. It was a part of the Ottoman book arts, together with illumination (tezhip), calligraphy (hat), marbling paper (ebru), and bookbinding (cilt). The words taswir or nakish were used to define the art of miniature painting in Ottoman Turkish. The studios the artists worked in were called Nakkashanes.

The miniatures were usually not signed, perhaps because of the rejection of individualism, but also because the works were not created entirely by one person; the head painter designed the composition of the scene, and his apprentices drew the contours (which were called tahrir) with black or colored ink and then painted the miniature without creating an illusion of third dimension. The head painter, and much more often the scribe of the text, were indeed named and depicted in some of the manuscripts. The understanding of perspective was different from that of the nearby European Renaissance painting tradition, and the scene depicted often included different time periods and spaces in one picture. The miniatures followed closely the context of the book they were included in, resembling more illustrations rather than standalone works of art.

The colors for the miniature were obtained by ground powder pigments mixed with egg-white and, later, with diluted gum arabic. The produced colors were vivid. Contrasting colors used side by side with warm colors further emphasized this quality. The most used colors in Ottoman miniatures were bright red, scarlet, green, and different shades of blue.

The worldview underlying the Ottoman miniature painting was also different from that of the European Renaissance tradition. The painters did not mainly aim to depict the human beings and other living or non-living beings realistically, although increasing realism is found from the later 16th century and onwards. Like Plato, Ottoman tradition tended to reject mimesis, because according to the worldview of Sufism (a mystical form of Islam widespread at the popular level in the Ottoman Empire), the appearance of worldly beings was not permanent and worth devoting effort to. The Ottoman artists hinted at an infinite and transcendent reality (that is Allah, according to the Sufism's pantheistic point of view) with their paintings, resulting in stylized and abstracted depictions.

History and development

.jpg)

During the reign of Mehmed II, a court workshop called Nakkashane-i Rum that also functioned as an academy was founded in Topkapı Palace in Istanbul to create illuminated picture manuscripts for the Sultan and the courtiers.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the Herat workshop of Persian miniaturists was closed, and its famous instructor Behzad (or Bihzad) went to Tabriz. After the Ottoman emperor Selim I briefly conquered Tabriz in 1514, taking many manuscripts back to Istanbul, the "Nakkashane-i Irani" (The Persian Academy of Painting) was founded in Topkapı Palace for imported Persian artists. The artists of these two painting academies formed two different schools of painting: The artists in Nakkashane-i Rum were specialized in documentary books, like the Shehinshahname, showing the public, and to some extent the private, lives of rulers, their portraits and historical events; Shemaili Ali Osman—portraits of rulers; Surname—pictures depicting weddings and especially circumcision festivities; Shecaatname-wars commanded by pashas. The artists in Nakkashanei-i Irani specialized in traditional Persian poetic works, like the Shahnameh, the Khamsa of Nizami, containing Layla and Majnun and the Iskendername or Romance of Alexander, Humayunname, animal fables, and anthologies. There were also scientific books on botany and animals, alchemy, cosmography, and medicine; technical books; love letters; books about astrology; and dream reading.

The reigns of Suleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566) and especially Selim II (1566–1574) in the second half of the 16th century were the golden age of the Ottoman miniature, with its own characteristics and authentic qualities. Nakkaş Osman (often known as Osman the Miniaturist) was the most important miniature painter of the period, while Nigari developed portrait painting.

Matrakçı Nasuh was a famous miniature painter during the reigns of Selim I and Suleyman the Magnificent. He created a new painting genre called topographic painting. He painted cities, ports, and castles without any human figures and combined scenes observed from different viewpoints in one picture.

During the reigns of Selim II (1566–1574) and Murat III (1574–1595), the classical Ottoman miniature style was created. The renowned miniature painters of the period were Nakkaş Osman, Ali Çelebi, Molla Kasım, Hasan Pasha, and Lütfi Abdullah.

By the end of the 16th century and in the beginning of 17th century, especially during the reign of Ahmed I, single page miniatures intended to be collected in albums or murakkas were popular. They had existed at the time of Murat III, who ordered an album of them from the painter Velijan. In the 17th century, miniature painting was also popular among the citizens of Istanbul. Artists under the name of "Bazaar Painters" (Turkish: Çarşı Ressamları) worked with other artisans in the bazaars of Istanbul at the demand of citizens.[2]

A new cultural genre known in Ottoman history as the Tulip period occurred during the reign of Ahmed III. Some art historians attribute the birth of the unique style called "Ottoman Baroque" to this period. The characteristics of the period carried the influences of French baroque. In this period, a grand festival for the circumcision rituals for the sons of Ahmed III was organized. Artisans, theatre groups, clowns, musicians, trapeze dancers, and citizens joined in the festivities. A book called Surname-i Vehbi tells about this festival. This book was depicted by Abdulcelil Levni (the name Levni is related to the Arabic word levn ("color") and was given to the artist because of the colorful nature of his paintings) and his apprentices. His style of painting was influenced by Western painting and very different from the earlier miniature paintings.

After Levni, Westernization of Ottoman culture continued, and with the introduction of printing press and later photography, no more illuminated picture manuscripts were produced. From then on, wall paintings or oil paintings on toils were popular. The miniature painting thus lost its function.

After a period of crisis in the beginning of the 20th century, miniature painting was accepted as a "decorative art" by the intellectuals of the newly founded Turkish Republic, and in 1936, a division called "Turkish Decorative Arts" was established in the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, which included miniature painting together with the other Ottoman book arts. The historian and author Süheyl Ünver educated many artists following the tradition of Ottoman book arts.

Contemporary miniature artists include Ömer Faruk Atabek, Sahin Inaloz, Cahide Keskiner, Gülbün Mesara, Nur Nevin Akyazıcı, Ahmet Yakupoğlu, Nusret Çolpan, Orhan Dağlı, and many others from the new generation. Contemporary artists usually do not consider miniature painting as merely a "decorative art" but as a fine art form. Different from the traditional masters of the past, they work individually and sign their works. Also, their works are not illustrating books, as was the case with the original Ottoman miniatures, but being exhibited in fine art galleries.

Gallery

-

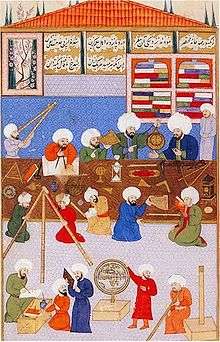

Ottoman astronomers at work around Taqī al-Dīn at the Istanbul Observatory

-

Ottoman Janissaries and the defending Knights of St. John, Siege of Rhodes, 1522

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ottoman miniatures. |

Further reading

- Osmanlı Resim Sanatı (Ottoman Painted Art), Serpil Bagci, Filiz Cagman, Gunsel Renda, Zeren Tanindi

- Aşk Estetiği (The Aesthetics of Divine Love), Beşir Ayvazoğlu

- Turkish Miniature Painting, Nurhan Atasoy, Filiz Çağman

- Turkish Miniatures: From the 13th to the 18th Century, R. Ettinghausen

- Ottoman miniatures and their downfall form the theme of the 1998 novel My Name is Red by Nobel-laureate Turkish author Orhan Pamuk.

Notes

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Illuminated manuscripts in the Topkapi Palace Museum. |

- Miniature Gallery from Levni and other famous artists

- About Surname-i Vehbi

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||