Oslofjord Tunnel

Coordinates: 59°39′53″N 10°36′47″E / 59.66472°N 10.61306°E

|

Hurum entrance | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Oslofjord |

| Route | National Road 23 |

| Start | Måna, Frogn |

| End | Verpen, Hurum |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 14 April 1997 |

| Opened | 29 June 2000 |

| Owner | Norwegian Public Roads Administration |

| Toll | NOK 30–130 |

| Vehicles per day | 6,827 (2012) |

| Technical | |

| Length | 7.306 km (4.540 mi) |

| Number of lanes | 3 |

| Operating speed | 70 km/h (43 mph) |

| Lowest elevation | −134 m (−440 ft) |

| Width | 11.5 m (38 ft) |

| Grade | 7% |

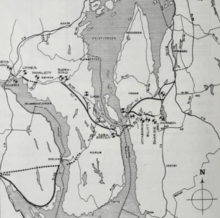

The Oslofjord Tunnel (Norwegian: Oslofjordtunnelen) is a subsea road tunnel which traverses the Oslofjord, connecting Hurum and Frogn in Norway. Carrying three lanes National Road 23, the 7,306-meter (23,970 ft) long tunnel reaches a depth of 134 meters (440 ft) below mean sea level. The tunnel has a maximum gradient of seven percent. It acts as the main link connecting Buskerud with Follo and Østfold, supplementing the Moss–Horten Ferry which runs further south.

The crossing was originally served by the Drøbak–Storsand Ferry, which commenced in 1939. Plans for a fixed link were launched in 1963, originally based on two bridges which would connect to Håøya. Plans resurfaced in the early 1980s with the advent of subsea tunneling technology and the Oslo Airport location controversy, which proposed airports in Hurum, Ås and Hobøl. Even though Gardermoen was ultimately build as the airport, the tunnel had raised sufficient support to be built irrespectively. Parliament gave approval on 13 December 1996 and construction started on 14 April 1997. The tunnel was official opened on 29 June 2000 and was financed in part by a toll, collected by Bompengeselskapet Oslofjordtunnelen at a toll plaza in Frogn.

The tunnel was flooded in 2003 and 2008 and experienced a landslide in 2003. All of these incidents resulted in the tunnel being closed for weeks. There have been two major truck fires, one in 2006 and one in 2011. After the latter incident, the tunnel has been closed for heavy traffic exceeding 7.5 tonnes. In an effort to eliminate the problem, the Public Roads Administration has proposed building a second tube.

Specifications

The Oslofjord Tunnel is a 7,306-meter (23,970 ft) long subsea tunnel which constitutes part of National Road 23 and is hence part of the Trans-European road network. The tunnel traverses below Drøbaksundet of the Oslofjord, reaching a maximum depth of 134 meters (440 ft) below mean sea level. The tunnel has three lanes, with one used as a climbing lane in the uphill direction to overcome the seven percent gradient. It has a speed limit of 70 kilometers per hour (43 mph), which is enforced by traffic enforcement cameras.[1] The tunnel has a width of 11.5 meters (38 ft) and was at the time of construction build after criteria for a traffic of up to 7,500 vehicles per day.[2]

The tunnel is equipped with 25 evacuation rooms. These can be sealed off from the main tunnel and can each provide pressurized space for thirty to fifty people while a fire is being fought.[3] There is a natural flow of 1,800 litres (400 imp gal; 480 US gal) of sea- and ground water into the tunnel every minute. To handle this a pump system is installed capable of draining 4,000 litres (880 imp gal; 1,100 US gal) per minute.[4] There is a natural reservoir under the tunnel able to retain 5,000 cubic meters (180,000 cu ft) of water, which can act as a buffer.[5] It can also be used as a water source for the fire department.[6] The tunnel is built with continual concrete elements to ensure better protection against water leaks.[2] The structure has received artistic decorations in the form of gobo lighting.[7]

The tunnel is indefinitely closed for vehicles exceeding 12 meters (39 ft) in length.[8] From the onset it was designed to be expanded to two tubes, hence a second tube was designed to be built on the south side.[9] National Road 23 is 40.2 kilometers (25.0 mi) long and runs from the E18 at Kjellstad in Lier through the municipalities of Røyken and Hurum to the E6 at Vassum in Frogn. The section from Bjørnstad in Røyken to Vassum was built at the same time as the tunnel and is referred to as the Oslofjord Link (Norwegian: Oslofjordforbindelsen). The crossing primarily serves as a quicker link connecting Buskerud to Follo and Østfold. Alternative crossing involve driving north via Oslo or south via the Moss–Horten Ferry.[1] The route saves 25 kilometers (16 mi) and 30 minutes compared to driving via Oslo.[10]

The tunnel is owned and operated by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration. As part of a national road, its operation and maintenance is financed by the national government. Toll collection is carried out by Bompengeselskapet Oslofjordtunnelen AS, a limited company owned in equal shares by Akershus County Municipality and Buskerud County Municipality. They have subcontracted the operations of their administration and the toll plaza to Vegfinans.[11] Undiscounted toll prices are NOK 60 for cars and NOK 130 for trucks (vehicles exceeding 3.5 tonnes). Payment is automated through Autopass.[12] The tunnel experienced a traffic an average 4,432 vehicles per day in 2003. The average annual peak was reached at 7,138 in 2010, before falling to 6,827 in 2012.[13] The road is owned and maintained by the Norwegian Public Roads Administration as a nationally financed project.[9]

History

Planning

The connection between Follo and Hurumlandet was originally served by the Drøbak–Storsand Ferry, a service operated by Bilferjen Drøbak–Hurum. Planning of the ferry service commenced in 1939 and its first ferry, Leif 1, serve the crossing until 1954. It was then replaced with Drøbaksund, which was itself replaced with the larger Drøbaksund II in 1968. The company took over the Svelvik–Verket Ferry, which connects Hurumlandet to Vestfold, in 1971. Drøbaksund I was put into service in 1978 and Drøbaksund III in 1985. From 1993 it was supplemented with Hurumferja, hence the service having two ferries.[14] The ferry had a daily traffic of 320 vehicles in 1980.[15]

A fixed crossing of Hurumlandet and the Oslofjord was first proposed by Anton Grønsand in 1958.[16] It was followed up in a regional transport plan published in 1963, with a horizon of forty years. Road planning was in the following decade reorganized so that most planning fell within the jurisdiction of a single county. As a crossing of the Oslofjord invariable would have to cross a county border, plans fell outside the natural planning framework.[17] As the idea fell out of the main workload of planners, a limited company, A/S Fjordbroene, was established in 1967. Initiated by Hurum Municipality, it was also partially owned by larger companies in the municipality.[16] It attempted to revitalize the proposal and launched a detailed plan in 1974 which called for two bridges which would connect each side of the fjord to the island of Håøya. The cost of the project was steep, the Håøya bridges alone estimated at 510 million 1981 Norwegian krone (NOK). The plans were rejected by the road administration because of the steep cost and low traffic prognosis, while others criticized the environmental impact it would create on Håøya and at the towns of Svelvik and Drøbak.[17]

Interest in the project was rekindled in the late 1970, when the subsea Vardø Tunnel was planned and later built. The choice of a subsea tunnel alternative would allow for major costs savings, easily shaving away half the cost. Another contributing factor was the Oslo Airport location controversy, which proposed various locations for a new airport. A fixed crossing would be allow for a fixed service from Vestfold and Buskerud if an airport was located in Hobøl or Ås, and it would allow for a fixed service from Follo and Østfold if the airport was located in Hurum. Also the construction of a new plant at Tofte Cellulosefabrikk was expected to give a large rise in lumber transport to the region and could contribute to cross-fjord traffic.[18] Previous analysis had been based on traffic data collected for other uses, so in 1980 a dedicated traffic survey was carried out.[19]

A report from 1982 recommended that construction be carried out in two phases. First a road departing from the E18 at Jessvoll near Drammen through Røyken and then under the fjord before terminating at an intersection with the E6. The second phase would see the construction of a road from the tunnel through Hurum to Verket, in a new subsea tunnel under the Drammensfjord near Svelvik and then through a tunnel to Sande, where it would intersect with the E18.[20] Cost estimates for the tunnel ranged between NOK 200 and 360 million.[21] The plans were based on partially using part of National Road 154 in Buskerud for part of the feeder road. Cost estimates for the auxiliary road system was estimated at between NOK 340 and 400 million, depending on the amount of reused road and the standard chosen.[22]

The bridge alternative had some proponents during the 1980s. It was proposed consisting of the Drøbak Bridge, a three-pylon cable-stayed bridge with main spans of 600 and 570 meters (1,970 and 1,870 ft), respectively, with the central pylon placed on Askholmen. On Håøya the route would largely run through a 2-kilometer (1.2 mi) tunnel. Across Vestfjorden the road would cross on another three-pylon cable-stayed bridge with main spans of 590 and 530 meters (1,940 and 1,740 ft), with the central pylon placed on Stedgrunnen.[23] The bridge could also serve as possible route for the Hurum Line, a railway which was proposed to link the new airport to the capital.[24] Fjordbruene worked for a bridge alternative, but also made detailed plans for a tunnel.[16] The tunnel plans were passed unanimously by the municipal councils in Røyken and Frogn in February 1986[25][26] and by a large majority in Akershus County Council in April.[27] By 1988 three of the four bridge alternatives had been vetoed by the Norwegian Armed Forces.[28] On 21 June Action Against a Bridge was established in Drøbak and had more than 2,000 members within days.[29]

Parliament voted on 8 June 1988 to build the new national airport at Hurum. The decision included a four-lane motorway-crossing of the Oslofjord. The Public Roads Administration published six alternatives for a crossing, including four bridge alternatives, a conventional tunnel and an immersed tube. Planning halted in 1990 after the airport construction decision was shelved. By then only the Socialist Left Party in Hurum Municipal Council being opposed. Without the airport traffic, the profitability in the project fell through and the Public Roads Administration called to instead prioritize other investments. However, Minister of Transport and Communications Kjell Opseth was a staunch supporter of the Oslofjord Link, in part as a compensation for the loss of the airport after it in 1992 was decided to be built at Gardermoen.[16]

The Public Roads Administration landed in 1992 at a bridge alternative as their preferred solution,[30] backed among others by the Norwegian Haulier’s Association and Hurum Municipality. The former stated that a bridge would result in trucks consuming only half as much fuel on the segment, while the latter was also enacted by the prospect of the bridge becoming a tourist attraction.[31] On the other hand the bridge was met with protests from environmental organizations and residents of Drøbak and the ministry thus decided to go for a tunnel. A full-scale construction was debated, with two tubes and a new highway all the way to Lier.[30]

Opseth announced in January 1994 that he favored a tunnel over a bridge, stating that decisive weight had been laid on costs. The tunnel was estimated to cost NOK 1.25 billion, while a bridge would cost NOK 170 million more. Opseth's also announced that he favored a motorway alternative with twin tubes and four lanes.[32] The project was partially met with opposition in Parliament, as for instance Magnus Stangeland of the Center Party stated that other projects should be prioritized.[33] New estimates showed reduced traffic and the issue ended in a compromise: one tube would be built and a new road would only be built as far west at Bjørnstad in Røyken.[30] Financing was secured through a combination of state grants and tolls. The tolls were financed through private debt accumulated by Bompengeselskapet Oslofjordtunnelen, owned jointly by Akershus County Municipality and Buskerud County Municipality and established in late 1995.[34] The single tube reduced the total construction cost to NOK 1,041 million. To cut costs further, plans to build northwards and westwards from Hurum were placed on hold. Thus the new auxiliary road network was limited to 26.9 kilometers (16.7 mi), including the tunnel itself. The toll portion of the investments were set at NOK 699 million.[35]

Frogn Municipal Council attempted to veto the development in November 1995, by demanding that either two or no tubes be built. The ministry stated that they would if necessary pass state zoning laws to avoid such disruptions.[36] The municipal opposition rested in part on opposition to building a new road through a recreational forest area and the auxiliary road would come too close to the settlements at Heer.[6] After the municipal council voted against rezoning, a new zoning plan was thus legislated by the ministry and Frogn Municipal Council lost further ability to participate in the planning. The ministry also decided that the road would be designated National Road 23 and be treated as a trunk route. The tunnel was expected to see a quintupling of the traffic compared to the ferry service.[37] By June 1996 commitments from the Labour and Conservative Party ensured a majority in Parliament for the link.[38] The project was passed by Parliament on 13 December 1996, against the votes of the other parliamentary parties.[39]

Construction

The contract for blasting the tunnel, worth NOK 347 million, was awarded to Scandinavian Rock Group. Construction commenced on 14 April 1997.[40] In addition to attack from both ends, blasting was also carried out from a 700-meter (2,300 ft) long crosscut on the Hurum side.[6] A major accident took place on 9 October, when a pile of stones fell onto a worker.[41] Most of the tunneling took place through bedrock gneiss. However, in January 1998 the tunnelers met a wall of sediments. Although projected, it turned out to be more than 10 meters (33 ft) thick, instead of the expected 5 meters (16 ft), delaying the project with six weeks. The segment was overcome by injecting concrete to create a shell before removing the masses.[42] Thus a 300-meter (980 ft) diverting tunnel was blasted in a curve under the area to allow work to continue while work continued on the weak zone.[43] The issue added NOK 30 million to the construction costs.[44] The zone, created by an ancient river, was overcome by freezing the section and then blasting through it.[10] Then a 1.2-meter (3 ft 11 in) thick and 40-meter (130 ft) long concrete shell was built to give the area structure.[45] The tunneling was completed on 4 February 1999.[46]

Throughout and past the construction there was a disagreement between Southern Follo Fire Department and the Public Roads Administration regarding the installation of camera surveillance for fire protection. The former stated that the installation would be required in relation to national regulations, while the latter stated that the fire chief lacked technical qualifications to assess fire protection in tunnels. The installation would cost between NOK 3 and 10 million.[47] The issue was resolved by the Directorate of Public Roads in December 1999, in favor of not installing surveillance.[48] On the other hand the tunnel was the first to receive a system which automatically detects vehicles carrying hazardous materials and can inform the fire departments of all of them should an incident occur.[49] It can also keep track of the numbers of vehicles in the tunnel at any given time.[45]

Erik Wessel was contracted to install artwork in the tunnel.[7] The rest of the Oslofjord Link saw a further five tunnels and eight bridges.[10] The tunnel and the new National Road 23 was opened by King Harald V on 29 July 2000 at 13:00. The ferry service was at the same time terminated.[45] It was the 17th subsea tunnel in Norway.[6] It was Europe's longest subsea road tunnel when it opened, although the title was captured by the Bømlafjord Tunnel the following year.[10] The road's initial tolls were NOK 25 for motorcycles, NOK 50 for cars and NOK 110 or 220 for trucks.[40]

Incidents

The tunnel flooded on 16 August 2003 after the automatic pumping system failed to sufficiently drain the natural reservoir for water. This caused the pumps to malfunction and it took a week to drain the tunnel for 3,000 cubic meters (110,000 cu ft) of water and allow it to open. This was the first time such an event occurred in a subsea tunnel in Norway.[4] A 12-tonne concrete section fell down 28 December 2003,[50] causing the tunnel to close for a week. The tunnel was closed again on 16 January 2004 after geological surveys found a section of unstable rock.[51] Further surveys revealed that the geological evaluations during construction had overestimated the quality of the rock and hence not implemented sufficient countermeasures.[52] As a temporary measure a tentative ferry service was established from February.[53] The issues cost NOK 35 million to resolve,[54] and the tunnel could re-open on 2 April.[55]

A fire broke out in a truck carrying paper on 23 June 2011. Thirty-four people were caught in the smoke-engulfed tunnel, of which twelve were sent to hospital. The cause of the incident was an escalated fire in the engine. The tunnel was thus closed for all traffic.[56] As a temporary measure, two morning and two afternoon rush-hour free ferries were put into service between Drøbak and Sætre.[57] The tunnel re-opened on 7 June, although vehicles with a weight exceeding 7.5 tonnes were not permitted to use it.[56] Despite the regulation, the police caught several trucks and buses still using the tunnel.[58]

The speed limit was reduced from 80 to 70 kilometers per hour (50 to 43 mph) on 7 September 2011. This resulted in a doubling in the number of issued speeding tickets, with 1,200 tickets issued in the first month.[59] From March 2012 the weight restriction was lifted, but instead replaced by a length limitation of 12 meters (39 ft), in an attempt to allow smaller commercial vehicles to use the tunnel.[60] To cover necessary upgraded to improve the tunnel's safety, Parliament awarded a grant of NOK 40 million in May.[61] The most extensive investment was the construction of 26 evacuation rooms.[62] With these installations in place the Public Roads Administration hoped to re-open the tunnel for heavy traffic, but the decision was vetoed by Southern Follo Fire Department.[3]

The debt incurred by the toll company was paid off by August 2013.[63] The company had by the collected NOK 1,400 million, twice the debt incurred. The remainder was used for interest and to operate the toll plaza, which cost NOK 14 million in 2012.[64] In March 2012 the Public Roads Administration, based on the plans to build a second tube, announced a prolonging of the toll period, initially with another three years. The agency stated that advanced tolls on a new tube would allow for a lower total toll collection, as interest payments would be lowered. In addition the tolls would stimulate for less traffic through the tunnel, which the agency wanted to reduce until a second tube opens. Should the second tube not be built, the tolls will be used for other projects in the area.[63]

Future

The Public Roads Administration announced on 10 January 2012 that they intended to build a second tube for the tunnel along with a second carriageway on the section of National Road 23 from the tunnel to the Vassum Interchange on E6 in Frogn. The investment was proposed financed through an extension of the toll collection for an additional twelve to fifteen years.[62] Construction is proposed to start in 2016 and the new tube may be opened in 2019.[65] The project is estimated to cost NOK 2.4 billion.[66]

The second tube is planned located parallel with the current tube, shifted 250 meters (820 ft) to the side, to be built south of the current tube. This will allow each of the tubes to act as an emergency exit for the other.[67] This design was built into the original plans, in which the road administration anticipated building the crossing as a full motorway in two phases.[9] The two tubes will be connected by emergency exits every 250 meters (820 ft). The second tube will have to closely follow the route of the current tunnel, thus eliminating the possibility of a less steep gradient. The Public Roads Administration regards the section through sediments at Hurum as the most challenging part and is considering altering the tunnels positions, both horizontally and vertically, through this part.[68]

The 6-kilometer (3.7 mi) section of highway between Måna and Vassum is proposed upgraded to four-lane motorway standard. This involves rebuilding the roundabout at Måsa to an interchange, construction of a parallel tube for the 1,610-meter (5,280 ft) Frogn Tunnel, a parallel bridge for the 212-meter (696 ft) Bråtan Bridge and a reconstruction of Vassum Tunnel, which acts as a gradient between a single- and twin-tubed tunnel.[69] Should the project be carried through, the toll collection is proposed prolonged until 2028.[70]

The ministry asked for alternatives, and two bridge proposals were but forward in 2013. The one involves the original crossing via Håøya, estimated to cost NOK 7 billion.[66] Of this, NOK 5 billion would be for the bridges and would have a total length of 13 kilometers (8.1 mi).[71] The second involves a suspension bridge to be build further south in Drøbaksundet, from Vestby, estimated to cost NOK 10 billion.[66] It would have a main span of between 1,300 and 1,500 meters (4,300 and 4,900 ft) and demand 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) of new road. The latter bridge allows for a railway to be carried as well.[71]

Should a bridge be built, the tunnel would be closed. Finalizing a proposal in time for completion by 2019 is regarded by the authorities as crucial, as by that time European Union regulations will be enforced, requiring the tunnel, because its location on a Trans-European Network, to have two tubes or a parallel evacuation tunnel. Alternatively, a new bridge could be built further south to replace the Moss–Horten Ferry. The latter would see the Oslofjord Tunnel remain open, and could or could not result in a second tube being built. The ministry has stated that planning of a bridge would not be completed before 2020.[66]

References

- 1 2 "Dagens Oslofjordforbindelse" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Alteren (2004): 7

- 1 2 Brenden, Lars (2012). "Oslofjordtunnelen oppgradert men ikke nok". Brannmannen (in Norwegian). Oslo Brannkopsforening.

- 1 2 "Stengt i minst én uke". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). 18 August 2003. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Nestvoll, Veslemøy (18 August 2003). "Tunnelvann fortsatt en gåte". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Width, Henrik (24 June 1997). "Oslofjordtunnelen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 17.

- 1 2 "Lager lys i tunnelen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 26 July 2000.

- ↑ "Her kan det bli 15 nye år med bompenger" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Norwegian Public Roads Administration (2013): 5

- 1 2 3 4 "Ferjefri fjordkryssing". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). 29 June 2000.

- ↑ "Om Oslofjordtunnelen" (in Norwegian). Bompengeselskapet Oslofjordtunnelen. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Priser og betaling" (in Norwegian). Bompengeselskapet Oslofjordtunnelen. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Årsdøgntrafikk trafikkregisteringspunkt Akershus" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 2013. p. 25. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Om oss/Historikk" (in Norwegian). Ferjeselskapet Drøbak–Hurum–Svelvik. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Asplan (1980): 25

- 1 2 3 4 Messel (2004): 429

- 1 2 Asplan (1982): 21

- ↑ Asplan (1982): 22

- ↑ Asplan (1982): 23

- ↑ Asplan (1982): 37

- ↑ Asplan (1982): 41

- ↑ Asplan (1982): 45

- ↑ Styri (1988): 44

- ↑ Styri (1988): 58

- ↑ Visle, Elisabeth (18 February 1986). "Enstemmig ja til tunnel i Frogn". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 16.

- ↑ "Enstemmig formannskap i Røyken vil ha fjordtunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 14 February 1986. p. 3.

- ↑ "Ja i fylkestinget: Akershus for Drøbaktunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 23 April 1986. p. 28.

- ↑ Hvattum, Torstein (9 July 1988). "Forsvaret vil ha tunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 8.

- ↑ "2000 protester mot Drøbakbro". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 6 July 1988. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Messel (2004): 430

- ↑ Sjølli, Morten (17 December 1991). "Lastebileierne går mot Drøbaktunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 10.

- ↑ Solvoll, Einar (19 January 1994). "I fire felter under Oslofjorden". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- ↑ Width, Henrik (25 November 1995). "Stangeland: Østlandet har fått nok kroner". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 26.

- ↑ "Bompenger til Drøbaktunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 30 October 1995. p. 4.

- ↑ Width, Henrik (24 November 1995). "Hundretalls millioner mangler". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 19.

- ↑ Sjølli, Morten (28 November 1995). "Sier nei til en Drøbak-tunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 4.

- ↑ Grue, Øystein (14 May 1996). "Ny omstridt riksvei i havn Trang fødlse for Oslofjordtunnel". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 5.

- ↑ Width, Henrik (29 June 1996). "Flertall for tunnel under Oslofjorden". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 4.

- ↑ Width, Henrik (14 December 1996). "Oslofjordtunnelen: Første salve i februar". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- 1 2 Width, Henrik (13 April 1997). "Første smell for Oslofjord-tunnelen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- ↑ "Skadet i Oslofjordtunnelen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 10 October 1997. p. 9.

- ↑ Solli, Berit (26 January 1998). "Møter ukjent berggrunn under Oslofjorden Løsmasser skaper problemer med Oslofjordtunnelen". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- ↑ Saltbones, Ingunn (29 January 1998). "Må lage ekstratunnel". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). p. 31.

- ↑ Wormnes, Are (8 October 1998). "Oslofjordforbindelsen: Lekker lite vann og penger". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Sæter, Kjetil (30 June 2000). "Kongen åpnet Oslofjordforbindelsen – En gammel drøm er realisert". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- ↑ "Tørrskodd forbindelse 130 meter under Oslofjorden". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 5 February 1999. p. 10.

- ↑ Sundnes, Trond (11 June 1999). "Statens vegvesen til motmæle: –Brannsjefer mangler kunnskap". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 12.

- ↑ "Avslår video-overvåking i Oslofjord-tunnelen". Aftenposten Aften (in Norwegian). 20 December 1999. p. 15.

- ↑ "Økt tunnelsikkerhet". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 28 June 2000. p. 2.

- ↑ Alateren (2004): 3

- ↑ Sætran, Frode (16 January 2004). "Nytt rasfarlig fjellparti oppdaget i Oslofjordtunnelen Stengt igjen på ubestemt tid". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 3.

- ↑ Rostad, Knut (30 January 2004). "Stenges". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). p. 20.

- ↑ "Midlertidig bilferje over Drøbaksundet" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 4 February 2004.

- ↑ Rostad, Knut (14 February 2004). "Tabber til". Verdens Gang (in Norwegian). p. 21.

- ↑ "Oslofjordtunnelen gjenåpnes 2. april" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 28 March 2004.

- 1 2 "Oslofjordtunnelen åpnet igjen". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 8 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Smaadal, Camilla (28 June 2011). "Setter inn gratisferje Drøbak-Hurum". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Havnaas, Torun (11 July 2011). "Trosset forbudet for tunge kjøretøy". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Smaadal, Camilla (5 October 2011). "Doblet antall fartsbøter etter at farten ble satt ned". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Kvitle, Mette (13 March 2012). "Oslofjordtunnelen stengt for kjøretøy over 12 meter". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Connell, Ragnhild Ask (5 October 2011). "40 mill. til Oslofjordtunnelen". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Aarset, Henning (10 January 2012). "Foreslår to løp i Oslofjordtunnelen". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Larsen, Gunnar (31 May 2012). "Vil kreve bompenger i Oslofjordtunnelen i tre år til". Drammens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Thoner, Kristoffer (8 January 2013). "Bilister har betalt dobbelt opp for Oslofjordtunnelen" (in Norwegian). TV 2. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Fakta" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Hultgren, John (1 February 2013). "Slik kan du kanskje krysse Oslofjorden i 2026". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Nytt løp i Oslofjordtunnelen" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ Norwegian Public Roads Administration (2013): 7

- ↑ "Rv. 23 Måna - Vassum utvides til 4-felts veg" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ↑ "Finansiering" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Public Roads Administration. 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- 1 2 Seehusen, Joachim (1 February 2013). "Vil ha bru over Drøbaksundet". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Retrieved 19 September 2013.

Bibliography

- Alteren, Bodil (2004). Sikkerhet i Oslofjordtunnelen (PDF) (in Norwegian). Trondheim: SINTEF. ISBN 82-14-02728-4.

- Asplan (1982). Ferjefri forbindelse mellom E6 og E18 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Ministry of Transport and Communications.

- Messel, Jan (2000). Hurums historie 1900–2000 (in Norwegian) III. Hurum: Hurum kommune. ISBN 82-91796-88-2.

- Norwegian Public Roads Administration (2013). Planprogram Rv. 23 Oslofjordforbindelsen - Byggetrinn 2 (PDF) (in Norwegian).

- Styri, Hans Jakob (1988). Fakta om hovedflyplass: Gardermoen eller Hurum? (in Norwegian). Oslo: Polarforlaget. ISBN 82-90544-00-6.

External links

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||||||