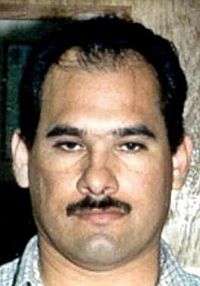

Osiel Cárdenas Guillén

| Osiel Cárdenas Guillén | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

May 18, 1967 Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Ethnicity | Mestizo |

| Citizenship | México |

| Occupation | Gulf Cartel's drug lord |

| Known for |

Drug lord and murder |

| Home town | Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

| Predecessor | Juan García Abrego |

| Successor | Heriberto Lazcano, Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, Ezequiel Cárdenas Guillen |

| Criminal charge | Money laundering, drug trafficking, murder, threatening law enforcement agents[1] |

| Criminal penalty | Drug trafficking[1] |

| Criminal status |

Incarcerated Term: 25-year prison sentence[1] Location: Federal prison, Colorado, USA.[1] |

| Notes | |

|

Arrested in 2003. | |

Osiel Cárdenas Guillén (born May 18, 1967) is a former Mexican drug lord and the former leader of the Gulf Cartel (Spanish: Cártel del Golfo) and Los Zetas. Originally a mechanic in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, where he was born, he entered the Gulf Cartel by helping Juan García Abrego, the capo at the time; when García Ábrego was arrested in 1996, some infighting erupted within the cartel. Osiel Cárdenas eventually took control by killing his friend and contender Salvador Gómez, earning Cárdenas the nickname "El Mata Amigos" (The Friend-Killer).

As confrontations with rival groups heated up, Osiel Cárdenas sought and recruited over 30 deserters of the Mexican Army's elite Grupo Aeromóvil de Fuerzas Especiales (GAFE) to form part of the cartel's armed wing.[2] Los Zetas, as they are known, served as the hired private mercenary army of the Gulf Cartel.

After a shootout with the Mexican military in 2003, Osiel was arrested and imprisoned. In 2007 he was extradited to the U.S. and in 2010 he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for money laundering, drug trafficking, homicide, and for having threatened two U.S. federal agents in 1999.

Osiel's brother, Mario Cárdenas Guillén, worked for the Gulf Cartel, as did another brother, Antonio Ezequiel Cárdenas Guillen, who was killed by Mexican Marines on November 5, 2010.

Arrest of Ábrego

Following Juan García Ábrego's 1996 arrest by Mexican authorities and subsequent deportation to the United States, his brother Humberto García Ábrego tried to take the lead of the Gulf Cartel, but ultimately failed in his attempt.[3] He did not have the leadership skills nor the support of the Colombian drug-provisioners. In addition, he was under observation and was widely known, since his surname meant more of the same.[4] He was to be replaced by Óscar Malherbe de León and Raúl Valladares del Ángel, until their arrest a short time later,[5] causing several cartel lieutenants to fight for the leadership. Malherbe tried to bribe officials $2 million for his release, but it was denied.[6] Hugo Baldomero Medina Garza, known as El Señor de los Tráilers, is considered one of the most important members in the rearticulation of the Gulf Cartel.[7] He was one of the top officials of the cartel for more than 40 years, trafficking about 20 tons of cocaine to the United States each month.[8] His luck ended in November 2000 when he was captured in Tampico, Tamaulipas and imprisoned in La Palma.[9] After Medina Garza's arrest, his cousin Adalberto Garza Dragustinovis was investigated for allegedly forming part of the Gulf Cartel and for laundering money, but the case is still open.[10] The next in line was Sergio Gómez alias El Checo, however, his leadership was short lived when he was assassinated in April 1996 in Valle Hermoso, Tamaulipas.[11] After this, Osiel took control of the cartel in July 1999 after assassinating Salvador Gómez Herrera alias El Chava, co-leader of the Gulf Cartel and close friend of him, earning his name as the Mata Amigos (Friend Killer).[12]

Cárdenas era and Los Zetas

In 1997 the Gulf Cartel began to recruit military personnel whom Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, an Army General of that time, had assigned as representatives from the PGR offices in certain states across Mexico. After his imprisonment a short time later, Jorge Madrazo Cuéllar created the National Public Security System (SNSP), to fight the drug cartels along the U.S-Mexico border. After Osiel Cárdenas took full control of the Gulf Cartel in 1999, he found himself in a no-holds-barred fight to keep his notorious organization and leadership untouched, and sought out members of the Mexican Army Special Forces to become the military armed-wing of the Gulf Cartel.[13] His goal was to protect himself from rival drug cartels and from the Mexican military, in order to perform vital functions as the leader of the most powerful drug cartel in Mexico.[14] Among his first contacts was Arturo Guzmán Decena, an Army lieutenant who was reportedly asked by Osiel Cárdenas to look for the "best men possible."[15] Consequently, Guzmán Decenas deserted from the Armed Forces and brought more than 30 army deserters to form part of Cárdenas’ new criminal paramilitary wing.[16] They were enticed with salaries much higher than those of the Mexican Army.[17] Among the original defectors were Jaime González Durán,[18] Jesús Enrique Rejón Aguilar,[19] and Heriberto Lazcano,[20] who was killed in 2012 while being the supreme leader of Los Zetas. The creation of Los Zetas brought a new era of drug trafficking in Mexico, and little did Cárdenas know that he was creating the most dangerous drug cartel in the country.[21] Between 2001 and 2008, the organization of the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas was collectively known as La Compañía (The Company).[22]

One of the first missions of Los Zetas was to eradicate Los Chachos, a group of drug traffickers under the orders of the Milenio Cartel, who disputed the drug corridors of Tamaulipas with the Gulf Cartel in 2003.[23] This gang was controlled by Dionisio Román García Sánchez alias El Chacho, who had decided to betray the Gulf Cartel and switch his alliance with the Tijuana Cartel; however, he was eventually killed by Los Zetas.[24] Once Osiel Cárdenas Guillen consolidated his position and supremacy, he expanded the responsibilities of Los Zetas, and as years passed, they became much more important for the Gulf Cartel. They began to organize kidnappings;[25] impose taxes, collect debts, and operate protection rackets;[26] control the extortion business;[27] securing cocaine supply and trafficking routes known as plazas (zones) and executing its foes, often with grotesque savagery.[15] In response to the rising power of the Gulf Cartel, the rival Sinaloa Cartel[28] established a heavily armed, well-trained enforcer group known as Los Negros.[29] The group operated similar to Los Zetas, but with less complexity and success. There is a circle of experts who believe that the start of the Mexican Drug War did not begin in 2006 (when Felipe Calderón sent troops to Michoacán to stop the increasing violence), but in 2004 in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, when the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas fought off the Sinaloa Cartel and Los Negros.[30]

The death of Arturo Guzmán Decena (2002),[31] and the capture of Rogelio González Pizaña (2004),[32] the second-in-line, marked the opportunity for Heriberto Lazcano to take charge of Los Zetas. Upon the arrest of the Gulf Cartel boss Osiel Cárdenas Guillen in 2003 and his extradition in 2007, the panorama for Los Zetas changed—they began to become synonymous with the Gulf Cartel, and their influences grew greater within the organization.[33] Los Zetas began to grow independently from the Gulf Cartel, and eventually a rupture occurred between them in early 2010.[34][35]

Cárdenas' encounter with U.S. agents

In a November afternoon of 1999, Cárdenas learned that a Gulf Cartel informant was being transported through Matamoros, Tamaulipas, by the FBI and DEA.[36] According to the story mentioned in the interviews 11 years after this life-or-death incident, the DEA agent Joe DuBois and FBI agent Daniel Fuentes were riding in a white Ford Bronco with diplomatic plates along the streets of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.[37] For years, both were working for the disarticulation of the cartels in Mexico, and both knew how the drug cartels worked south of the border. In the back seat of the car, a Mexican informant from a local newspaper on crime coverage guided the two agents and gave them a tour on the city's drug routes and on the homes of the drug lords of the city. They even cruised by Cárdenas' house, a pink-colored mansion with tall walls, security cameras, armed guards and roof-snipers. Within moments, according to DuBois, a Lincoln Continental was on their tail, then a stolen pickup truck with Texan plates.[38] The federal agents were cut off and surrounded by at least five vehicles, including one by a former state police officer. Just yards away from Matamoros' police department, the agents were surrounded by a convoy of gunmen from the Gulf Cartel, which included Costilla Sánchez.[39][40][41] Some wore police and military uniforms.[42] Nearby, other men, also in police uniform, directed traffic.

Cárdenas and his men intercepted and surrounded the vehicle on a public street and demanded for the informant to be released to him.[43] According to the two agents, the Gulf Cartel sicarios outnumbered and outgunned them. Their only way out was to talk their way out.[44] Cárdenas arrived seconds later in a white Jeep Cherokee, approaching the two agents. In his waistband, he wore a Colt pistol with a gold grip; in his hands, a gold-plated AK-47.[45] Cárdenas pounded the Ford Bronco and calmly asked for the informant. Fuentes flashed his FBI badge, giving Cárdenas a smile. In an ongoing discourse, Cárdenas told the agents that he would shoot them if they did not surrender. The two agents refused to do so, saying they were dead either way. He gave them another choice: to hand over the informant. Again, they refused.[46]

DuBois, who grew up in Mexico and was a police officer in neighboring Brownsville, Texas, recalled how Cárdenas "did not give a damn who [they were]," while DuBois replied to him: "You don't care now, but tomorrow and the next day and the rest of your life, you'll regret anything stupid that you might do right now. You are fixing to make 300,000 enemies."[47] Then, Fuentes reminded Cárdenas how the U.S. launched a massive manhunt and investigation after the kidnap, torture, and assassination of the DEA agent Enrique Camarena in 1985 in Mexico.[48] All of the killers and accomplices were captured in that U.S. operation.[49]

After a tense standoff, DuBois and Fuentes, along with their informant, were released.[50] The two agents and the informant headed off to Brownsville, Texas. As for Cárdenas, the damage had been done by taking on the U.S. government, which placed pressure on the Mexican government to apprehend Cárdenas. The two agents, Joe DuBois and Daniel Fuentes, were recognized by the U.S. attorney general for their 'exceptional heroism,' and both are still on the job.[51] The Mexican informant is living somewhere in the United States.[52]

Kingpin Act sanction

On 1 June 2001, the United States Department of the Treasury sanctioned Cárdenas Guillén under the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (sometimes referred to simply as the "Kingpin Act"), for his involvement in drug trafficking along with eleven other international criminals.[53] The act prohibited U.S. citizens and companies from doing any kind of business activity with him, and virtually froze all his assets in the U.S.[54]

Cárdenas' arrest and extradition

Osiel Cárdenas Guillén was captured in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas, on March 14, 2003 in a shootout between the Mexican military and Gulf Cartel gunmen.[55] He was one of the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives, which was offering $2 million for his capture.[56] According to government archives, this six-month military operation was planned and carried out in secret; the only people informed were the President Vicente Fox, the Secretary of Defense in Mexico, Ricardo Clemente Vega García, and Mexico's Attorney General, Rafael Macedo de la Concha.[57] After his capture, Osiel Cárdenas was sent to the federal, high-security prison La Palma.[58] On May 1, 2008, while still in jail, Cárdenas threw a 'Day of the Child' party for 2,000 people in Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila, complete with banners, ponies, clowns, food and music.[59] However, it was believed that Cárdenas still controlled the Gulf Cartel from prison,[60] and was later extradicted in 2007 to the United States, where he was sentenced to 25 years in a prison in Houston, Texas for money laundering, drug trafficking, homicide and death threats to U.S. federal agents.[61] Reports from the PGR and El Universal state that while in prison, Osiel Cárdenas and Benjamín Arellano Félix, from the Tijuana Cartel, formed an alliance. Moreover, through handwritten notes, Osiel gave orders on the movement of drugs along Mexico and to the United States, approved executions, and signed forms to allow the purchase of police forces.[62] And while his brother Antonio Cárdenas Guillén led the Gulf Cartel, Osiel still made vital orders from La Palma through messages from his lawyers and guards.[62]

The arrest and extradition of Osiel, however, caused several top lieutenants from both the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas to fight over important drug corridors to the United States, especially the cities of Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and Tampico—all situated in the state of Tamaulipas. They also fought for coastal cities Acapulco, Guerrero and Cancún, Quintana Roo; the state capital of Monterrey, Nuevo León, and the states of Veracruz and San Luis Potosí.[63] Through his violence and intimidation, Heriberto Lazcano took control of both Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel after Cardenas’ extradition.[64] Lieutenants that were once loyal to Cárdenas began following the commands of Lazcano, who tried to reorganize the cartel by appointing several lieutenants to control specific territories. Morales Treviño was appointed to look over Nuevo León;[65] Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez in Matamoros;[66] Héctor Manuel Sauceda Gamboa, nicknamed El Karis, took control of Nuevo Laredo;[67] Gregorio Sauceda Gamboa, known as El Goyo, along with his brother Arturo, took control of the Reynosa plaza;[68] Arturo Basurto Peña, alias El Grande, and Iván Velásquez Caballero alias El Talibán took control of Quintana Roo and Guerrero;[69] Alberto Sánchez Hinojosa, alias Comandante Castillo, took over Tabasco.[70] However, continual disagreement was leading the Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas into an inevitable rupture.

United States v. Cárdenas-Guillén

In 2007, Osiel Cárdenas was extradited to the United States and charged with the involvement of conspiracies to traffic large amounts of marijuana and cocaine, violating the "continuing-criminal-enterprise statute" (also known as the "drug kingpin statute"), and for threatening two U.S. federal officers.[71] The standoff the two agents had with the drug lord in 1999 in the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas led for the U.S. to indict Cárdenas and pressure the Mexican government to capture him.[72] In 2010 he was finally sentenced to 25 years in prison after being charged with 22 federal charges;[73] the courtroom was locked and the public prevented from witnessing the proceeding.[74] The proceedings took place in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas in the border city of Brownsville, Texas.[75] Cárdenas has been isolated from interacting with other prisoners in the supermax prison he is in.[76]

Nearly $30 million of the former drug lord's assets were distributed among several Texan law enforcement agencies.[77] In exchange for a twenty-five year sentence, he agreed to collaborate with U.S. agents in intelligence information.[78] The U.S. federal court awarded two helicopters owned by Osiel Cárdenas to the Business Development Bank of Canada and the GE Canada Equipment Financing respectively, and both of them were bought from "drug proceeds."[79]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "El origen de 'Los Zetas': brazo armado del cártel del Golfo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 5 July 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ↑ "‘Los Zetas’ se salen de control". El Universal. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Castillo, Gustavo (2 May 2009). "Desplazan a los García Ábrego en liderato del cártel del Golfo". La Jornada.

- ↑ Alzaga, Ignacio (2009-05-01). "Relegan a familia de García Ábrego en cártel del Golfo". Milenio Noticias.

- ↑ Weiner, Tim (January 19, 2001). "Mexico Agrees To Extradite Drug Suspect To California". New York Times.

- ↑ Lupsha, Peter. "A Chronology | Murder, Money, & Mexico". University of New Mexico.

- ↑ Medellín, Alejandro (02/04/2011). "Medina Garza en 'La Palma'". El Universal. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Zendejas, Gabriel. "Detectan a poderoso capo del Cártel del Golfo". La Prensa. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ↑ Ruiz, José Luis (3 April 2001). "Caen 21 miembros de cártel del Golfo". El Universal.

- ↑ "Indagan a familiar de El Señor de los Tráileres". Milenio Noticias. 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Ramírez, Ignacio (04/10/2000). "La disputa del narcopoder". El Universal. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Desde las entrañas del Ejército, Los Zetas". Blog del Narco. 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "¿Quienes son los Zetas?". Blog del Narco. 7 March 2010. Archived from the original on July 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Cártel de 'Los Zetas'". Mundo Narco. 2011-01-15.

- 1 2 Grayson, George W. (2010). Mexico: narco-violence and a failed state?. Transaction Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 1-4128-1151-1.

- ↑ Tobar, Hector (May 20, 2007). "A cartel army's war within". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Los Zetas and Mexico's Transnational Drug War". Borderland Beat. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "Los 'grandes capos' detenidos en la guerra contra el narcotráfico de Calderón". CNN México. 6 November 2010.

- ↑ "Video Interrogatorio de Jesús Enrique Rejón Aguilar "El Mamito"". Mundo Narco. July 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano "El Verdugo"". Blog del Narco. 3 March 2010.

- ↑ Ware, Michael (August 6, 2009). "Los Zetas called Mexico's most dangerous drug cartel". CNN World.

- ↑ Sherman, Chris (25 January 2012). "Texas jury convicts alleged Mexican cartel hit man". The Monitor. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "Surge nuevo 'narcoperfil". El Universal. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "Organized crime and terrorist activity in Mexico, 1999-2002" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ Schiller, Dane. "Narco gangster reveals the underworld". Houston Chronicle.

- ↑ "The Mexican Drug War and the Thirty Years’ War". Bellum: The Stanford Review. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ↑ "Army troops capture a Zetas cartel boss in northern Mexico". Fox News Latino. February 15, 2011.

- ↑ "¿Qué es el Cartel de Sinaloa?". Perfil.com. 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Sánchez, Alex (June 4, 2007). "Mexico’s Drug War: Soldiers versus Narco-Soldiers". New American Media | La Prensa San Diego.

- ↑ Fantz, Ashley (22 January 2012). "Saldo por el combate al narcotráfico: muerte por un negocio millonario". CNN Mexico. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ↑ Sullivan, Kevin (June 21, 2004). "Betrayal on the Mexican Border". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Sánchez, Jesús Olguín. "Cae líder de los "Zetas"". México: Presidencia de la República. Retrieved 3 November 2004.

- ↑ "Drug Trafficking Organizations". National Drug Intelligence Center. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "Weekend shootouts in northeastern Mexico kill at least 9". CNN News. 17 June 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ "El origen de 'Los Zetas': brazo armado del cártel del Golfo". CNN México. 5 July 2011.

- ↑ "OPERATION IMPUNITY II". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Retrieved December 2000. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "U.S. agents targeting Mexican drug kingpin". Associated Press: Deseret News. Dec 15, 2000.

- ↑ "DEA agent tells details of now-infamous 1999 confrontation with Mexican drug kingpin". Dallas Chronicle.

- ↑ "DEA agent describes engaging in armed standoff with drug kingpin in '99". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Olga R. (12 September 2012). "Capture of Gulf Cartel general highlights bad day for drug-world figures". The Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ↑ "DEA agent describes engaging in armed standoff with drug kingpin in '99". Lubbock Avalanche Journal. 16 March 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ↑ Bracamontes, Ramón (2011-02-17). "Attack on ICE agents won't slow drug war, experts say". El Paso Times.

- ↑ "Drug Kingpin Turned Informant Sentenced in Secrecy to 25 Years". Frank A. Rubino, Esq. PA.

- ↑ "DEA agent talks of standoff with Mexican drug lord". KrisTV.com | 6 News. Mar 15, 2010 11:44 AM. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Osiel Cardenas transfered [sic] to a top-security Supermax prison". Wednesday, May 18, 2011. Borderland Beat.

- ↑ Buch, Jason (February 28, 2011). "Dangers higher for federal agents". San Antonio Express.

- ↑ S chiller, Dane (March 15, 2010). "DEA agent breaks silence on the standoff with cartel". Chron: Houston & Texas News.

- ↑ "Enrique Camarena: Death of a Narc". TIME Magazine. March 1988.

- ↑ Malone, Michael. "The Enrique Camarena Case" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- ↑ "Grayson: Zapata slaying will have repercussions". Brownsville Herald. February 17, 2011.

- ↑ "48th Annual Awards Ceremony". U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved July 28, 2000. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "DEA agent talks of 1999 Matamoros standoff with Osiel Cardenas-Guillen". Brownsville Herald. March 15, 2010.

- ↑ "DESIGNATIONS PURSUANT TO THE FOREIGN NARCOTICS KINGPIN DESIGNATION ACT" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. 15 May 2014. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "An overview of the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. 2009. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "'Drug boss' captured in Mexico". BBC News. 15 March 2003. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ↑ "Osiel Cardenas-Guillen". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Cae Osiel Cárdenas: Se enfrentó a tiros con el Ejército". El Universal. 15 March 2003.

- ↑ "Nuevo auto de formal prisión a Osiel Cárdenas". Esmas.com. August 2005.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ "Happy Children’s Day, Love Grandpa Cocaine". Border Reporter. 1 May 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ Aponte, David (01/05/2005). "Líderes narcos pactan en La Palma trasriego de droga". El Universal. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Sentencian a Osiel Cárdenas Guillén a 25 años de prisión en Texas". CNN México. 24 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Maneja Osiel mafia desde la carcel, prueban". El Universal. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ "Desertor del Ejército, nuevo líder del cártel del Golfo: informes castrenses". La Jornada. 3 February 2008.

- ↑ "Detienen a un líder del Cártel del Golfo en Tabasco". Esmas.com. 2008-09-07.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ "Miguel Morales Treviño, Z-40, un narco violento ya está en la mira". Mundo Narco. 2010-12-22.

- ↑ "Loz Zetas: Grupo Paramilitar Mexicano" (PDF). Policias y Sociedad. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "Cartel leader believed slain in Reynosa violence". The Monitor. February 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Confirman militares enfrentamiento con narcotraficantes". El Mañana: Reynosa. November 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Revelan que desertor del Ejército mexicano liderea Cártel del Golfo". El Porvenir. 3 February 2008.

- ↑ "Capturan al líder de los ‘Zetas’ en Tabasco". Tabasco Hoy. 8 September 2008.

- ↑ "United States of America v. Cardenas-Guillen" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Southern District of Texas. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ "DEA agent talks of 1999 Matamoros standoff with Osiel Cardenas-Guillen". The Brownsville Herald. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ "Extradition: Past cases highlight limits". The Brownsville Herald. 5 March 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ Langford, Terri (9 November 2011). "New U.S. attorney no stranger to Houston". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ Perez, Emma (23 September 2008). "Cardenas Guillen awaits trial". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ Schiller, Dane (30 September 2011). "Mexican drug lords decry U.S. prison conditions". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ "Assets from drug boss go to Texas law enforcement". The Houston Chronicle. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ Schiller, Dane (4 August 2011). "Trafficking defendant: I was a DEA informer". The Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. turns over custody of Cardenas-Guillen helicopters to businesses". The Monitor. 29 March 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|